A.J.S. Rayl • Sep 30, 2008

The Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Embarks on New Endeavour, Spirit Gets Back To Normal Schedule

It's been a September to remember for the Mars Exploration Rovers with Spirit producing enough power to return to its science assignments on a daily basis and Opportunity commanding the spotlight once again as it embarked on a long journey toward a new, humongous crater and one of the most ambitious adventures undertaken on the mission.

After driving out of Victoria Crater in the final days of August, Opportunity spent a few Martian sols investigating the three sets of tracks it's made over the last couple of years at Duck Bay, then roved back toward the crater to check out a classic Martian ripple at the rim. There, the rover, which suffers from frozen shoulder, and its handlers “practiced new techniques” for how to reach its instrument deployment device (IDD) targets, said Sharon Laubach, the integrated sequencing team chief, who oversees mission managers, rover planners, and most of the people who sequence the commands that turn the scientists' objectives into the instructions sent to the rovers.

Opportunity then headed toward an area the team named in honor of desert explorer Ralph Alger Bagnold. “It looked like the cleanest patch of Meridiani dust that we’ve seen anywhere,” said Steve Squyres, of Cornell University, the principal investigator for rover science. And the MER science team was anxious to determine its composition with its mineral detecting instruments.

Located on the lee side of the rim, the target was in “a little dust trap that also turned out to be a nasty little rover trap,” said Squyres. Opportunity slipped repeatedly trying to scale the ridge leading to the chosen target within Bagnold, Laubach said, so the MER team instructed the rover to abandon that assignment and rove on toward its next major destination.

“We did our best to get to Bagnold, but it became clear after a few sols that we were just wasting our time,” Squyres said. “We could try for months and never get to it, so it was time to go.”

On September 22, NASA and the MER team announced exactly where Opportunity would go next – a giant crater to the southeast. At 22-kilometers (13.7-miles) in diameter and 300 meters (984 feet) deep, this hole in the ground is more than 20 times larger than Victoria Crater, “staggeringly large compared to anything we've seen before," as Squyres put it.

"This is a bolder, more aggressive objective than we have had before," noted JPL's John Callas, project manager for MER. "It's tremendously exciting."

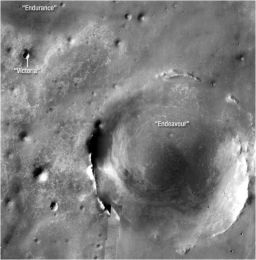

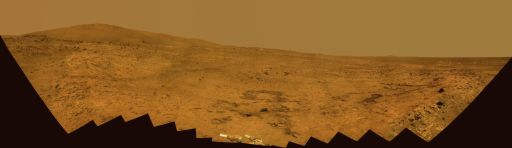

Opportunity's next big destination

Opportunity's next big destinationThe MER team has chosen a a crater more than 20 times wider than Victoria Crater as Opportunity's next destination. The rover began the long, 12-kilometer (about 7.5-mile) journey -- which p.i. Steve Squyres estimates will take about 2 years, with science stops along the way -- on Friday, Sep. 26, 2008 with a 152-meter drive. The crater, which is to the southeast of Opportunity's location at Victoria, dominates this orbital view from the Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) camera onboard Mars Odyssey. Victoria is the most prominent circle near the upper left corner of the image. This view is a mosaic of about 50 separate visible-light images taken by THEMIS.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / ASU

It’s also the largest formation or object that the MER team has targeted and the team has provisionally named this crater Endeavour. Actually, this is the first moniker of a rover destination that the team has officially suggested to the International Astronomical Union (IAU), which officiates over the naming of landmarks on other planets.

“We’ve been using famous ships in exploration as our theme for naming craters ever since we got to Meridiani and I’d wanted to stick with that theme, but for a crater this big we are abiding by the IAU rules,” said Squyres.

The IAU rules regarding craters on Mars smaller than 60 kilometers is that they be named for towns on Earth that have a population of less than 100,000. As it turns out, Endeavour, theoretically anyway, should satisfy everyone concerned.

If the IAU accepts the MER team’s suggestion, Opportunity’s next major destination will officially be named for Endeavour, Saskatchewan, population 118, and the ship with which Captain James Cook discovered Australia. Interestingly, American country singer-songwriter Johnny Cash makes a reference to Endeavour in his song "The Girl in Saskatoon" . . . "I left a little town a little south of Hudson Bay."

To reach the crater provisionally named Endeavour, Opportunity will have to drive approximately 12 kilometers (about 7.5 miles) to the southeast, a long, long way even for this robot heroine. In fact, it's slightly more than the distance the rover has traveled since landing in the Meridiani Plains back in January 2004. "We may not get there," Squyres admits. "But it is scientifically the right direction to go anyway." That's because as the rover drives southward, the scientists expect to find younger rock layers on the surface and older cobbles that may have come from craters larger and deeper than Victoria.

Still, it’s an ambitious goal and given that the rovers are 4 years and 9 months into a mission that was originally "warrantied" for 3 months, Opportunity will have to pick up the pace if it’s going to get to this crater in its lifetime. Rover engineers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) where Spirit and Opportunity were designed, built, and are being managed, estimate the may be able to travel about 110 yards each day, according to Laubach. If Opportunity is able to maintain that pace, the journey will take, by Squyres’ estimate, about 2 years.

While the odds seem long indeed, everyone on the MER team -- and likely the millions of rover fans around the world – know better than to bet this rover won't make it. Beyond the fact that the MER team has nearly 5 years experience operating the rover, Opportunity has two new resources going for it, neither of which were available during the trek toward Victoria Crater -- a new version of flight software that boosts the rover’s ability to autonomously choose routes and avoid hazards such as sand dunes, and the dramatic imagery of the surface from the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), which can resolve terrain details, like dangerous rover-trapping ripples, as small as 10 centimeters (3.9 inches) tall, as well as other potential hazards.

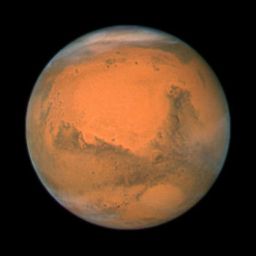

Mars

MarsNASA's Hubble Space Telescope took this close-up of Mars when it was just 88 million kilometers – 55 million miles – away. This color image was assembled from a series of exposures taken with the Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 within 36 hours of the planet's closest approach on December 18, 2007 at 11:45 p.m. Universal Time Mars and Earth have a "close encounter" about every 26 months, because of differences in the two planets' orbits. Earth goes around the Sun twice as fast as Mars, lapping the Red Planet about every two years. Both planets have elliptical orbits, so their close encounters are not always at the same distance. In its close encounter with Earth in 2003, for example, Mars was about 20 million miles closer than it is in the 2007 closest approach, resulting in a much larger image of Mars as viewed from Earth in 2003.

Credit: NASA, ESA, Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA), J. Bell (Cornell), and M. Wolff (SSI, Boulder)

Beyond those mission enhancements, Opportunity has been blessed by a series of Martian brush-offs during the last three months as wind gusts have cleared some of the accumulated dust on its solar arrays, amping up its power levels past 650 watt-hours in September. In short, this rover is powered up and ready to roll and neither Opportunity nor its planners are wasting any time.

Last Friday, September 26, Opportunity put the pedal to the metal and logged an impressive 152 meters (about 498 feet) on its odometer, according to Squyres.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the planet, at Gusev Crater, Spirit kept its rover nose to the grindstone from its parked position just off the north edge of Home Plate, the volcanic formation it's been studying for 2 years. While Opportunity has grabbed the limelight consistently over the last several months, Spirit has steadfastly, methodically continued snapping panoramic camera (Pancam) images for its third, grand landscape mosaic, as well as monitored the dust in the atmosphere, and otherwise conserved power through the brutally cold Martian winter.

“Spirit is doing fine,” reported Squyres. “Everybody is kind of eager to get moving, but we have to wait for the power levels are high enough before we do it.”

Things are looking up. Just last week, the rover crossed the power threshold and, after months of working reduced hours in "winter ops,” the team returned to nominal planning, or, in other words, its regular daily work schedule, Laubach informed. That means there is science in every sol. "Because we were able to achieve the 250 watt-hours, we're now back on 3 planning cycles a week and back to our normal schedule," she confirmed, "so things are getting back to normal for Spirit."

“We’re not driving obviously, but the other instruments can be active, so it makes sense for us to plan frequently enough to take advantage of all the power that we do have and we’re continuing to work our way through the Bonestell Pan,” said Squyres.

The rover, which is using its stereo Pancam "eyes" to shoot the thousands of images needed its third lush winter panorama is now making excellent progress. "We've completed approximately 75% of the Bonestell panorama, although not all of that data is downlinked from the rover yet,” said Jim Bell, lead scientist for the Pancam. “We've got about 20 pointings left, so depending on power levels, downlink data volume levels, and other rover health issues, we might be able to finish this in perhaps 2-3 weeks.”

As for the rovers’ health, both Spirit and Opportunity passed their daily physicals this month with flying colors and all subsystems on each vehicle are performing as expected.

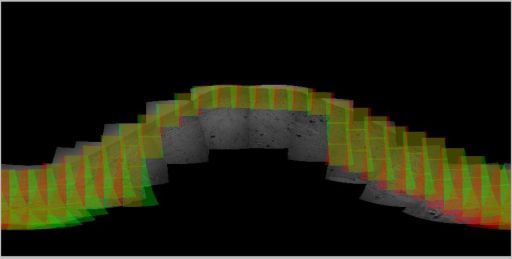

A work in progress

A work in progressThis image shows the Pancam team's planning map of what Opportunity has taken so far of the Bonesetll Pan and what's left to go. "We just finished the top row this past week, having decided recently to switch to a strategy of finishing the rows first, rather than the columns, to maximize our azimuthal coverage most quickly," said Jim Bell, Pancam lead. "We think it will all still mosaic well as long as the atmospheric dust level stays low).

Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell / Jim Bell & Pancam uplink team

Spirit From Gusev Crater

As August turned to September, the skies over Gusev Crater continued to clear. The tau, a measure of the atmospheric opacity caused by suspended dust in the Martian atmosphere, dropped from 0.274 to 0.218, translating to slightly less dust in the skies as this month got underway. It's a dramatic difference from a year ago, when the team was preparing for the possibility that Spirit would have to be put, effectively, on life support to survive its third Martian winter.

With the skies continuing to brighten and the temperatures warming, the rover's power production increased slightly from 235 to 245 watt-hours, edging closer to the 250 watt-hours threshold for which the team has been waiting since the Martian winter solstice on June 25. Once it is able to sustain that level of power, Laubach said, Spirit will be able to "bump" or move slightly from its parked position off the northern edge of Home Plate to adjust its solar arrays to track the Sun.

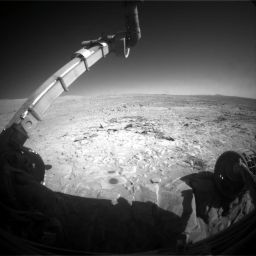

Spirit at Home

Spirit at HomeThis image shows Spirit at its current location on the northern edge of Home Plate in the Columbia Hills,at Gusev Crater. The picture was taken during the southern hemisphere winter solstice at about 2 p.m. local time on the rover's Sol 1591 (June 24, 2008). Home Plate is the elevated round and light toned mesa on the right side of the image. Spirit is visible at the large dark "bump" on the north-northeast edge of the circular volcanic formation. Mid-winter on Mars is the time of the clearest and least dusty atmosphere.

Credit: NASA / JPL / University of Arizona

Beyond taking its routine daily measurements of dust-related changes in the atmosphere, Spirit spent the first couple of days of September – Sols 1658-1659 – communicating – uplinking its science and engineering data to the Mars Odyssey orbiter to be transmitted to Earth and receiving new instructions from Earth via the its high-gain, X-band antenna.

The rover then took it easy for a while, recharging its batteries on Sols 1660-1663 (September 3-6 2008), and wrapping the first week of September by taking the photographs for another column of images for the Bonestell Panorama, using all 13 color filters of the panoramic camera (Pancam). Named for beloved space artist Chesley Bonestell, this the 360-degree view of its winter surroundings is already shaping up to be a jaw-dropper.

"We have been able to pick up the rate of imaging for the Bonestell Pan because of the increase in power," Laubach said. “Even during the reduced winter ops in the early part of the month, we were able to do more sections in the week than we had been able to do [in August]."

During the second week of September, Spirit continued its observations of the atmosphere and imaging for Bonestell, while the tau characteristically fluctuated .20, Following pretty much the same schedule as it did the first week of the month, the rover then spent Sols 1665-1666 (September 8-9, 2008) recharging, and on Sol 1667 (September 10, 2008), receiving its new assignments from Earth, as usual through its high-gain antenna, and relaying its science and engineering data to the UHF antenna on Odyssey for transmission to Earth. The following sol -- the seventh anniversary of 9/11 – Spirit checked out the dust accumulation on the Pancam mast assembly and took more images for the Bonestell Pan.

With the Martian winter slowly on the wane, the rover was requiring less and less energy for the heaters that keep its main batteries and the miniature emission thermal spectrometer (Mini-TES) warm at night. During the depths of the Martian winter, the rover was burning 90 watt-hours to maintain those survival heaters, but by mid-September it was requiring only between 30 and 40 watt-hours of its 245 total watt-hours to warm and protect both the batteries and the mineral-detecting science instrument, said Laubach.

Got dust?

Got dust?The global dust storm of June-July 2007 left a Sun-blocking haze in the atmosphere and a thick sunscreen of particles on Spirit's solar panels. As winter set in and the skies cleared after the storms, more and more dust fell and so far this rover has not been graced with any clearing wind gusts.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / USGS

Squyres and the science team members had wanted to do whatever it took to keep the highly-sensitive Mini-TES from breaking, because once spring comes Spirit will be leaving Home Plate to head out in search of more nearly pure silica and they really need the mineral detecting instrument to find it. Even though it had never gone a night without its survival heater, the MER team members had no way of knowing for sure if the Mini-TES had made it through the rover’s third Martian winter. They would soon find out.

The reduction in demand for power to preserve the Mini-TES and protects its main batteries this past month -- more than the painfully slow increase in Spirit’s solar-array input -- freed up energy for the dust-laden rover to step up its photography campaign in September. By the end of 9/11 on Mars, the rover had completed the top tier, one of three tiers needed for the final mosaic, according to Pancam lead Jim Bell.

On Sol 1671 (September 14, 2008), Spirit finished out the second week of the month by taking more Bonestell pictures, using all 13 color filters of the Pancam as usual, then using the camera to take spot images of the sky for calibration purposes.

Spirit's science schedule for the third week of the month basically duplicated the agenda of the first half of September. It took daily measurements of the dust in atmosphere opacity, then spent a couple of Martian days (Sols 1672-1673) to recharge and one (Sol 1674) to communicate, then went back to work on Bonestell on Sol 1675 (September 18, 2008).

That same worksol, the team decided it was time to find out if the Mini-TES had made it through the winter and instructed Spirit to calibrated the instrument. After warming up the actuator, they pointed the instrument up to measure atmospheric temperatures at different heights and then down to get the temperature of the ground. It was the first time since Sol 1558 (May 21, 2008) that the rover had used the instrument and team members were understandably a bit anxious.

Although the MER scientists normally would have used these observations to create a temperature profile of the ground and atmosphere, this time it was all about verifying that the spectrometer was still working after the long, cold period of disuse and to estimate the amount of dust on the optics that infiltrated the device during the fallout from the global dust storm of 2007. Remarkably, it seemed to be working as well as it had before.

Spirit arrives at winter haven

Spirit arrives at winter havenHuman explorers would be hard pressed to show more persistence than Spirit. After weeks of careful driving backwards dragging its broken front wheel, the rover finally made it to what team members call Home Plate North. It then gradually descended over the edge to get into position, as shown here, tilting its solar panels 13 degrees toward the sinking winter Sun to maximize its intake of light. Rover drivers plan to continue nudging Spirit forward, increasing the tilt, to track the Sun as it moves lower in the northern sky. The full-resolution version of this animation can be downloaded here (9.2 MB).

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

Spirit then took the next two sols to recharge and take it easy. By the end of the third week, the rover’s solar-array energy had inched upward to 255 watt-hours and the Martian skies cleared up again from the week before as the tau dropped to 0.14.

"Spirit has been in this mode where we've been doing reduced winter planning, so we had been preparing 2 planning cycles per week," said Laubach. "Our normal way of operating is we have different master sequence every sol that includes science activities."

The master sequence is essentially the sequence that coordinates the timing of everything the rover does and is in some sense “kind of a backbone,” Laubach explained. “The master sequences control when the rover will wake up or shut down, when it pauses activities, basically anything that requires time coordination, and they also, in turn, kick off sub-sequences that actually run the science activities, the drives, or IDD activities. For the reduced winter ops, we've had just one master for several sols at a time and science wasn’t always a part of those master sequences.”

The MER team, Laubach said, was waiting until the power eked up to a soild 250 watt-hours. “That's the magic number we were looking for. We wanted the confidence that the power production, generated by the solar arrays, would stay above 250 watt-hours –and that was our signal for when we could return to nominal planning and we just achieved that about a week ago,” she said. “Now we're back on 3 planning cycles a week, each master sequence includes science, and we’re back to our normal schedule."

As a result, work on the Bonestell Pan is picking up. "Now that we're on nominal ops we're able to do some of that almost everyday now,” Laubach said. “So we definitely have picked up the rate at which we can take these columns of pictures." No one could be happier than the Pancam team, or so one would think.

"From the engineering perspective, this is the most exciting news – and it is exciting for us – to be returning to 3 plans per week,” said Laubach. “You know how it's been for Spirit. As far as we're concerned, we’re back to nominal planning. That's a terrific change from the engineering point of view."

With Spirit having to hunker down in its parked position for so many months, Laubach admitted that she had pondered the team's morale. "Frankly, going into Martian winter solstice, I was concerned," she admitted. "Instead, I've gotten feedback from my team that it's been edge-of-the-seat exciting. Not for the rover planners – fortunately they've had Opportunity to go play with – but for my sequencers and uplink leads and mission managers. Having to deal with Spirit's living on the hairy edge of survival and to carefully manage when we plan and how often we can get telemetry and how many science activities can we can cram in there without pushing it over the edge has kept them really excited. Going into winter solstice, we didn't know what the tau was going to be like or the temperatures or the power draw for the heaters and we really thought we were going to lose the Mini-TES, if not the rover herself. But morale has been so high on the Spirit team and the rover pulled through and we have the Mini-TES,” she said. “We made it."

Bonestell Panorama, south view

Bonestell Panorama, south viewThis 180-degree panorama shows the southward vista from Home Plate North, where Spirit is spending its third Martian winter inside Mars' Gusev Crater. Home Plate, which is about 80 meters (260 ft) in diameter, is an eorded over volcanic formation. This view combines 168 different exposures that Spirit took with its panoramic Camera (Pancam) -- 42 pointings with 4 filters at each pointing. Spirit took the first of the images that are combined into this view on its Sol 1477 (Feb. 28, 2008), two weeks after the rover made its last move to reach the location where it would stop driving for the winter. Solar energy at Gusev Crater is so limited during the Martian southern hemisphere winter that the rover does not generate enough electricity to drive, nor even enough to take many images per day. The last frame for this mosaic was taken on Sol 1599 (July 2, 2008). Spirit is now working on taking the rest of the images for the northern half of the scene.The northwestern edge of Home Plate is visible in the right foreground. The blockier, more sharply shadowed texture there is layered sandstone whose layering is tilted inward toward the edge of the Home Plate platform. A dark rock on top of Home Plate in that area is a porous volcanic basalt unlike rocks nearby. The northeastern edge of Home Plate is visible in the left foreground. Spirit first climbed onto Home Plate on that region, in early 2006. In the center foreground, the turret of tools at the end of Spirit's robotic arm appears in duplicate because the arm was repositioned between the days when the images making up that part of the mosaic were taken. This is an approximate true-color, red-green-blue composite panorama generated from images taken through the Pancam's 750-nanometer, 530-nanometer and 430-nanometer filters. This "natural color" view is the rover team's best estimate of what the scene would look like if we were there and able to see it with our own eyes.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

The moment where it sort of collectively kicked in with the team that Spirit was going to beat the odds once again and survive yet another harsh Martian winter, was the sol when Spirit roved past winter solstice, said Laubach. "We were all waiting for solstice because we knew that was the bottom of the bathtub and even though it was still going to be a long climb out, that was the worst it could get.”

They know, of course, that's not absolutely true. “We have to wait and see what tau is going to do when the winds pick up,” Laubach noted. “But at least getting through this waiting game of making it through the winter was a big bump in team morale. We have these planning sheets, which are just pieces of paper that tell what sol we're planning that day and we stick them on the wall. The team took the one from solstice and everyone signed it. That's actually what gave me the sense the whole team feels like we've done it, we've accomplished this."

That planning sheet is now posted on the door outside the sequencing room. Talk about a collector's item. While it's as yet undetermined who will get to take that memento home, it would certainly make for one heck of an eBay item. But, Laubach said, "it's never going there."

Once Spirit did move through the winter solstice, there was, Laubach added "maybe a hint of frustration" that the power curve didn’t immediately shoot up so the rover could get back to doing things right away. “But the lights at the end of the tunnel are almost there,” she said. “Just one more month and we're going to be able to drive this girl.”

Hunkered down at Home

Hunkered down at HomeSpirit snapped this picture with its front hazard camera on Sol 1506 (Mar. 28, 2008) as it parked off the northern edge of the circular volcanic formation the team calls Home Plate, waiting out its third Martian winter. The rover continued its winter science campaign in September and by month's end was back on a normal schedule, conducting a fair amount of science every sol. There are hopes the rover will be able to "bump" or move slightly at the end of October.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

During the past week, Spirit has focused on Bonestell. Bell and the Pancam team are working hard with the rover to get it done for the obvious reason. “We know the team is getting antsy to move the rover again and with power levels slowly creeping back up, that's looking more and more like it could happen soon,” as Bell summed up.

Spirit, however, is still carrying a heavy load of dust on its solar arrays, compared to its twin. Its last significant dust clearing was in June 2006, while Opportunity has been gifted with various wind gusts just in the last several months. Fortunately, the skies over Gusev have been a lot clearer than the team predicted and the power demand on the survival heaters warm has decreased. “That has definitely helped," said Laubach. “It means that we can look forward to having enough power in late October to do this bump to angle the rover’s solar arrays toward the Sun."

Once the rover is able to follow the Sun and take in more fuel to increase its power levels to a comfortable level, then, said Squyres, “we’re going to blast off to the south as fast as we can.” There’s been no change in the long-term plan, he added. Von Braun and Goddard are still the rover’s next destinations.”

While everyone on the team is hoping spring will bring one of those helpful Martian gusts that will blow some of the thick layer of dust off solar panels, Spirit carries on. The engineers are still planning to direct the to do the first bump forward in October, Laubach confirmed.

Its two front wheels are positioned now on the top edge of the northern part of Home Plate, the circular volcanic formation that it’s been studying off and on for years, and the team is hoping the rover will have the traction to do that successfully. “There's no harm in trying it,” Laubach said. “If we can drive up, that would certainly be a nice shortcut, to go across Home Plate instead of going all the way around, which is what we would have to do to get to von Braun and Goddard."

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

After completing one of the most extraordinary scientific campaigns of the MER mission and more than 340 sols -- almost one Earth year -- inside Victoria Crater, Opportunity drove out and onto the Meridiani plains on its Sol 1634 (August 28, 2008), retracing the tracks it made about year ago when it entered the impact zone, crossing the potentially hazardous large ripple at the top of the slope at Duck Bay with relative ease.

The rover then spent the rest of that month taking snapshots of the surrounding terrain and the surface near its wheels with the navigation and hazard-avoidance cameras, measured argon gas in the Martian atmosphere with the alpha-particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS), took a six-frame, time-lapse movie in search of clouds with the navigation camera, and snapped some full-color images of a cobble called Isle Royale, before embarking on another short drive to acquire a full, 360-degree panorama of the area with the navigation camera.

On the first sol of September, Opportunity surveyed the horizon with the panoramic camera (Pancam), uplinked its stored data to the Mars Odyssey orbiter, then went into DeepSleep, a rest mode where in the rover shuts down all systems – including heaters – reminiscent in a way of how C3PO shuts down for the night in StarWars. It's a mode the rover has had to use almost since landing when the MER engineers discovered that one of the heaters was stuck in the "on" position and draining its precious life force.

In addition to conducting routine monitoring of atmospheric dust throughout the month and regularly taking argon measurements, Opportunity was able to maintain a rich science agenda in September, with its power levels averaging around 621 watt-hours.

On Sol 1639 (September 2, 2008), the rover woke up and took some pictures of a really dusty area on the lee side of the ripple at Victoria’s rim with its Pancam. The team decided to name this intriguing dust patch, which seemed to hold the most pure dust the MER team has ever seen at Meridiani Planum, for Ralph Alger Bagnold, an engineer and pioneer of desert exploration.

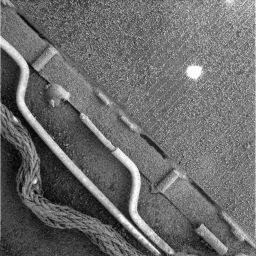

Farewell Victoria . . .

Farewell Victoria . . .From the crater rim, Opportunity gave a final salute to Victoria Crater, raising its robotic arm on its Sol 1639 (Sep. 2, 2008) and taking a snapshot of its shadow with the front hazard-avoidance cameras. The rover completed the salute by swinging the arm at its elbow joint back to the starting position.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

A veteran of World War I and the founder and first commander of the British Army's Long Range Desert Group during World War II, Bagnold completed the first recorded east-west crossing of the Libyan Desert in 1932. More pertinent to the MER mission, he is credited with having laid the foundations for the research on sand transport by wind in his influential book The Physics of Blown Sand and Desert Dunes (1941), which is still a primary reference in the field, used by NASA and planetary scientists for studying sands dunes on Mars.

The seeming purity of the dust in the Bagnold area was a real draw for the scientists and they decided to send their charge there to analyze what its composition was. “When we measure the composition of surface materials, we almost never measure a pure material,” said Squyres. “We’re almost always looking at some mixture of dust, sand, blueberries, bedrock, etcetera, and we’re often – except when we use the RAT – faced with the challenge of disentangling a mix of different materials. Obviously if you know the composition of any of the individuals components of the mix you can do that disentangling much more easily. So we’re always looking for pure material spectra and this is the purest cleanest looking dust deposit we’ve ever seen at Meridiani.”

First, Opportunity had to get there and make sure that it could get use its instruments, so it roved back toward Victoria and closer to the ripple, taking the typical post-drive images with its hazard-avoidance and navigation cameras. With plans to wrap up work at Duck Bay with a study of the ripple and Bagnold, the rover, at the end of that drive, the rover, in a symbolic gesture, gave a final salute to Victoria from its position at the crater rim, raising its robotic arm on and taking a snapshot of its shadow with the front hazard-avoidance camera.

After two years of studying this impact crater – which at the beginning of the mission was considered an almost impossible target -- it was for some on the team a sentimental moment. The rover completed the salute by swinging the arm at its elbow joint back to the starting position. It finished that worksol by measuring atmospheric argon with the alpha-particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS), then went into a mini-DeepSleep.

For the first two weeks of the month, Opportunity pretty much focused on imaging the tracks as Squyres noted it would do in the August MER Update, and conducting some practice sessions placing the spectrometers and microscopic imager on the instrument deployment device (IDD) on the ripple right at the entrance of Duck Bay.

Opportunity, which first began exhibiting signs of degradation on its shoulder joint on Sol 1502 (April 15, 2008), now must drive with its arm out front, in what the team calls the fishing position. It has also had to learn to use its arm in a new, more careful manner and the rover drivers selected the large sand ripple at the rim of Victoria Crater as an opportune target.

There, from Sols 1642-1647 (September 5-11, 2008), the rover and its handlers practiced going through the motions. It tested its ability to place the Mössbauer spectrometer, microscopic imager (MI), and APXS on specific targets in the vicinity of the crater rim.

"Since Opportunity's shoulder azimuth joint is frozen, we needed to test out our techniques for how we are now going to reach IDD targets,” said Laubach. "We've been developing new ways for her to move her arm and place the instruments and we're also creating new image products that help show what targets are reachable given that she can only reach targets in a plane now.”

The images and engineering data that Opportunity returned confirmed the tests “worked very well,” said Laubach, revealing in fact that the rover placed the instruments in position with very little error despite its disabled shoulder joint.

Sol 1644 (September 7, 2008), the rover relayed data to MRO for transmission to Earth. Typically, Opportunity relays data through Odyssey, but once a month, the rover uplinks to MRO in preparation for using it more in the future.

Opportunity also continued during the first half of September to study the Martian atmosphere, search for clouds by acquiring the traditional six-frame, time-lapse movies with the navigation camera, snap some more Pancam images of Bagnold, as well as a nearby cobble called Isle Royale and targets dubbed Schuchert and Drummond. It also devoted some science time to monitoring dust accumulation on the Pancam mast assembly and taking another 360-degree panorama of the area with the navigation camera. And, on Sol 1646 (September 10, 2008), the rover turned on its miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES) in an attempt to take a mini-survey of the sky and ground.

The Mini-TES on Opportunity has been out of commission since the global dust storm in 2007. Its mirrors are literally covered in the fine powder-like dust that is everywhere around Mars. But the MER team had the rover start-up the instrument because it’s going to “try something “really cool,” as Squyres put it.

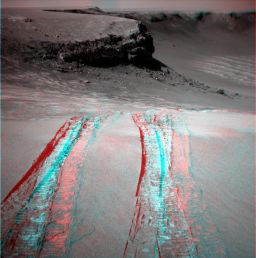

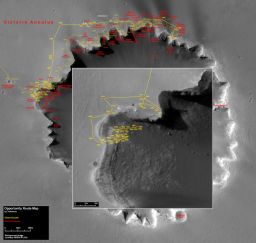

Opportunity's routes

Opportunity's routesEduardo Teishner has detailed Opportunity's routes up to the rover's Sol 1584 (July 8, 2008) over this image of Victoria Crater, taken by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (hiRISE) camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO. Credit: NASA / JPL / UA / E. Teishner

“Those of us who are old-timers on this mission remember that back at the beginning, when we were testing the vehicle, there was a test we ran one day on the Mini-TES elevation mirror, where we had accidentally set the control parameters for the mirror in a fashion that caused a sort of bizarre instability in the control electronics that made this thing move,” Squyres explained. “Rather than move appropriately, the thing kind of shook and jittered. You can never take data that way, so we realized – hey – don’t do that anymore. We wrote it up and that was that.” Until recently, that is.

“We tried it on one of the rovers on the ground, our test bed rover, a little while back and it shook just like it did then,” Squyres said. “It’s not a violent shaking, just a faint vibration really.”

The possibility that it could shake some of the dust off the contaminated mirror is just too tempting not to try. “To be honest with you, I don’t have particularly high hopes that it’s going to knock any dust off the mirror, but it is one card we still have to play, so we’re going to play it pretty soon,” Squyres said.

After taking a panel of images with the Pancam of a nearby cobble field on Sol 1648 (September 12, 2008), Opportunity stowed the robotic arm in its fishing position and began driving closer to Bagnold. Just before and after ending the drive, it took images with the hazard-avoidance and navigation cameras, as usual, then with the Pancam, it took a panel of images for what would become the Bagnold mosaic for the scientists and engineers to study.

On Sol 1650 (September 14, 2008), the rover continued driving toward Bagnold and documented progress before and after ending the drive by taking images with the engineering cameras, then snapped another panel of images for the Bagnold mosaic before sending data to Odyssey. Although the imaging of Bagnold went without issue, getting close enough to put the IDD down was another story.

Opportunity struggled to maneuver between two crests of the ridge surrounding Victoria Crater to get close enough to get its IDD instruments down on the dust. “The lip of the crater tends to be a place where these kind of big Aeolian drifts form and there were two of these drifts sort of arranged in echelon with a low spot in between them, which is where the dust collected,” explained Squyres.

Bagnold

BagnoldBagnold, visible toward the bottom of this panoramic camera (Pancam) image, is the dustiest patch seen at Meridiani to date. Opportunity struggled to make it close enough to take a look at it and analyze its composition with the devices on its instrument deployment device (IDD), but it slipped so much that the team decided it had to move on to a new Endeavour.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell University

The rover approached the ridge from the west, driving on flat ground, on Sols 1648 and again on Sol 1650 (September 14, 2008). Then, after reaching a sort of staging position, it tried to climb the ridge. The rover’s wheels, however, began slipping excessively on the sandy slope. “It was a situation where we had to kind of climb up to Bagnold and as we got closer and closer the wheels were sinking deeper and deeper and we were seeing slip numbers in excess of 98%,” said Squyres. “The wheels were turning and turning and turning and we weren’t going anywhere.”

Opportunity searched for clouds passing overhead with more six-frame, time-lapse, movies with the navigation camera on Sol 1652 (September 16, 2008), then checked for drift -- changes with time -- in the Mini-TES and conducted another test of the instrument on a target nicknamed Velvet, before beginning another attempt at getting close to Bagnold. No luck.

The following sol, Opportunity acquired a mosaic of westward-looking images with the navigation camera and took images in total darkness with the Pancam for calibration purposes, while the MER scientists and engineers huddled to figure out what to do about Bagnold. After discussing the situation, the MER team decided to give Opportunity one more chance by loosening the slip constraints and the rover bravely tried once more to get to Bagnold, but the attempt was, again, futile.

At that point, the team decided to abandon the effort. "The rover continued to encounter excessive slip, so we ended up deciding not to pursue that target any further,” said Laubach. “We took a lot of images, but we just could not do the in situ campaign."

“It became clear that this was just an unattainable goal,” added Squyres. “There was no way this rover could actually get to that spot and if we tried we were just going to dig ourselves in Purgatory style and never get to it. We did get some good image data, but it doesn’t tell us what the damn thing’s made of. We made a valiant effort, but the rover just did not have the traction to do it and we had to finally wave off and be on our way.”

In August, it looked like Opportunity might head back to the north/northeast after exiting Victoria crater, to conduct the long-awaited, much anticipated cobble campaign, then head toward another crater called Terra Nova. But during the last week of August and first week of September, Laubach received a request to have the rover drivers investigate techniques for driving Opportunity more than 100 meters a day, something the rover hadn’t done much since it first went to Endurance.

Clouds over Opportunity

Clouds over OpportunityPeriodically, Opportunity gazes skyward to watch water-ice clouds drifting overhead, as in this four-image sequence, spanning about 90 seconds, and taken on Sol 1614. There have not been many clouds to look at until recently, but the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter's MARCI camera has lately noticed more water-ice clouds over the rovers' equatorial positions.

Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell / Tman

Squyres had been considering heading to a huge crater to the south/southeast, far, far away crater for more than a year, but didn’t want to say anything about it until he was convinced it was a “credible” goal. “There’s no point in setting a goal if it’s obviously unattainable. If we were going to try to get to a crater 12 kilometers [7.5 miles] away with drives of 20-25 meters per sol, that would be pointless, because it would take so many years to get there. So I set – somewhat arbitrarily – the goal of being able to average 100 meters per drive sol on our way from here to the crater we provisionally called Endeavour. It’s a sensible number and we worked within the project to really do a hard-nosed assessment of whether or not that 100 meters per drive sol was actually achievable,” he said.

“You might say, well, it’s obvious that it shouldn’t be achievable, because post-Purgatory [Dune, where Opportunity was stuck for 6 weeks], we were averaging 15-20-25 meters per sol as we were driving southward,” he continued. “But several things changed since then that caused us to go off and do a reassessment. One is that we just have a lot more experience. Remember, with Purgatory it took us six weeks to get out of that. Then, with Jammerbugt (cksp) we got stuck and were out in like two days, because we had the experience form Purgatory. Then, more recently, we extracted ourselves from a nasty little rover trap at the lip of Victoria. So we know how to do that now.”

Two other key elements also factored into the team’s decision: the ability to see the rover's route in good detail with images from the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera onboard MRO which reveal what lies before the rover; and new, D-Star flight software uploaded onto both rovers about a year and a half ago, which gives the robot field geologists more capability of driving autonomously and avoiding obstacles or danger zones.

"Having the HiRISE images basically give us a very high-resolution map,” said Laubach. “We can see 10 centimeter tall (3.9 inches) ripples in the HiRISE images, as well as the route.”

“The HiRISE images are, frankly, the most important thing,” Squyres posited. “We didn’t have HiRISE images on our way to Victoria. Instead, we were faced with taking Navcam images and Pancam images off into the distance and trying to plan our route on the basis of those and it was tough to do,” he said.

Opportunity's DVD on Mars

Opportunity's DVD on MarsThis close-up of Opportunity's Mars DVD -- produced by The Planetary Society -- was created by the Student Astronauts, who participated in thte MER mission back in 2004. They combined three images captured through different filters on Opportunity's Sol 2 on Mars. Note the secret code around the edge.

Credit: NASA/JPL/Cornell/The Planetary Society

“If you read the journals of Captain James Cook and his voyage in the Endeavour,probably the most harrowing part of the entire voyage was trying to thread through the Great Barrier Reef,” he continued. “It’s a maze. Cook was looking ahead from the mast of the ship trying to see where the obstacles were and it was obviously very hard to see. They hit part of the reef and punched a hole in the bottom of the Endeavour and, in fact, if they hadn’t gotten a piece of coral jammed in there that helped stopped the leaking, they probably would have sunk right then and there. If he would have had aerial photos or satellite photos, he probably would have just sailed right through, because he would have known where everything was,” he said.

“It doesn’t matter if it’s James Cook or Opportunity, it helps to have the overhead view,” Squyres underscored. “That’s what gave us the confidence we could do that. We have the HiRISE images and so we have a roadmap from here to the crater, and the rover has the D-Star flight software to help guide in on the ground. When you combine those with the experience gained in the last four and a half years, I think we can do 100 meters a drive sol,” he said. “That is what made us decide to set this new crater 12 kilometers to the south as a goal and to announce it to the world.”

NASA and the MER team made that announcement on September 22: “Opportunity is setting its sights on a crater more than 20 times larger than its home for the past two years,” the press release began. The really big hole in the ground that the team has provisionally named Endeavour is 22-kilometers (13.7-miles) in diameter, 300 meters (984 feet) deep), and 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) away, which is a little more than the distance the rover has traveled since landing in January 2004. But, it likely holds a much deeper stack of rock layers than those examined in Victoria Crater and a new window that will take the team further back in time. And that is just too compelling. But it’s more than that.

“We could have decided to do is just go noodling around out on the plains, sniffing at cobbles until the wheels fall off,” said Squyres. “But you know, that just didn’t feel to me like the right thing to do. These are the Mars Exploration Rovers. We decided that it would be good to set a really challenging, maybe impossible goal for ourselves, then take on the challenge of trying to meet it.”

Last Friday (Sol 1662), Opportunity accepted the challenge, put its pedal to metal, and took off, swiftly logging 152 meters. “It’s the longest drive we’ve done in more than a thousand (1000) sols and we were all very excited by that,” said Squyres. “We did 30 meters with D-Star in that 152 meter drive. That’s something you have to be a real rover geek to appreciate that, but 30 meters of D-Star is quite an accomplishment. We are real proud of that.”

A base map for Opportunity's future travels

A base map for Opportunity's future travelsOpportunity's travels have taken it a long way, from its landing in Eagle crater (almost invisible in this image) to its next stop, Endurance (a tiny dark hole near the upper left corner), and on to Victoria, a fresh, sharp-edged crater that is visible above center, to the left of this image, with a prominent dark streaks fanning out of its northern rim. To date, the wheels have rolled through about 10 kilometers of odometry (though it's not been quite that long as the Martian crow flies). Now, Opportunity will be heading southeast, on a journey taking it 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) across Meridiani Planum to a huge crater, cut off at the lower right corner of this image. This image was taken by the Context Camera on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. The "click to enlarge" version is a quarter of the full resolution; click here for a full-resolution image (PNG format, 9 MB).

Credit: NASA / JPL / MSSS

"Right now we're in this very benign terrain, in the annulus around Victoria Crater and we're trying to pick up as much distance per sol as we can,” said Laubach. For now, there’s not a Purgatory-like dune in site. The team will encounter dune fields along the way, but at this point the road ahead promises smooth sailing.

Opportunity will not just be driving hell bent to get to this new crater. Actually, the rover isn’t even really finished with Victoria yet. “It's roving not too far from the rim, driving counterclockwise around Victoria in the other direction from 2005 tour,” Laubach said.

“Our goal is to drive right past Cape Pelar to the north end of Cape Victory – Magellan would have called it Cabo Victoria -- and then imaging Cape Pelar which is the next promontory,” Squyres said. “That’s our objective for the next few sols. Then we’re going to the next promontory to the south and image across of the southern side of Cape Victory. And then, we’re going to hit the gas.”

The cobble campaign has not been abandoned. “It's just shifted location and will be done in parallel with these big drives to the south,” Laubach said. “After every drive we'll be taking a lot of imagery and looking for opportunistic targets.”

“We’re looking for the right cobbles, cobbles that are of the geometry that is appropriate for using the IDD on them given the problems that we’ve had with Opportunity’s shoulder joint,” Squyres elaborated. “When we see a good cobble we’re going to stop, but we don’t want to exercise that shoulder joint much and we certainly don’t want to move it outside a very narrow range of acceptable positions. So we’re looking for cobbles that are pretty big and pretty flat.”

Since Endeavour is about the same distance that the rover has traveled since first bouncing down on Meridiani, Squyres estimates that the journey with the science stops along the way to the new big crater will take 2 years. It is, to say the least, a serious commitment.

“Are we going to get there?” Squyres asked, anticipating the question on almost everyone’s mind. “I have no idea. It’s the right direction to go anyway scientifically,” he noted. "I would love to see that view from the rim," he said. "But even if we never get there, as we move southward we expect to be getting to younger and younger layers of rock on the surface. Also, there are large craters to the south that we think are sources of cobbles that we want to examine out on the plain. Some of the cobbles are samples of layers deeper than Opportunity will ever see, and we expect to find more cobbles as we head toward the south."

Beyond the prospects of finding younger rock layers and old cobbles on the surface, Opportunity’s new destination has sent “a surge of energy” through the project. “Everybody’s fired up and everybody’s excited,” said Squyres. “The team is on top of their game in a way that is very gratifying to see, so this is a good goal in a lot of ways. We’ve been at Victoria Crater for 2 years now, and down inside of it for a year. The scenery didn’t change much for us in the last year. We were doing good science, but it was time to move on and take on a new challenge and the goal of getting to this very large crater has energized the whole project.”

"This gives the team something really exciting to try and accomplish," Laubach agreed. "Opportunity is a tough little girl and we're smarter than ever now about how to drive her and she has better software now, the D-Star algorhythm, that that we're eager to really try out. We completed a test before we went into Victoria Crater, but that was the only opportunity we had had to use it, so here's this great chance to see how that works in the dappled dune terrain. They team had been watching eagerly to see what Steve and John and project management would come up with for Opportunityonce we got out of the crater and they're ready for the challenge. They are so happy. The whole team, from Steve and John on down to all my sequencers and especially my rover drivers are just thrilled. We are exploring."

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth