A.J.S. Rayl • Sep 01, 2011

Mars Exploration Rover Update: Opportunity Finds Martian Mystery at Endeavour Crater

More than seven and a half years after landing, Opportunity arrived at its long-anticipated destination, the rim of Endeavour Crater, and in less than three weeks found something strange enough to launch a new Martian mystery, and with it a whole new mission for the Mars Exploration Rover team, mission leaders announced at a press teleconference earlier today.

The endless flat, bedrock and sand dune rippled plains of Meridiani have given way to rocks and boulders and hills and a huge crater rim rich with geologic gold that reveals a Mars long, long ago.

Opportunity has only had the chance to really check out one rock in the new locale, but it’s “different from any rock ever seen on Mars," said Steve Squyres, of Cornell University, the principal investigator for the Mars Exploration Rovers (MER) mission.

"It feels like the beginning of the mission," Squyres added. "I remember vividly press briefings [in 2004] where we presented new results that raised more questions than they answered … and we have some strange stuff going on here. You're coming along with us to a brand new field site.”

Apparently excavated by an impact that dug a small crater the size of a tennis court into Endeavour's rim, the rock, dubbed Tisdale 2, is flat-topped, about the size of a footstool, and it boasts surface compositional differences that distinguish it from anything the robot field geologist has studied. "It has a composition similar to some volcanic rocks, but there's much more zinc and bromine than we've typically seen,” said Squyres.

Tisdale 2

Tisdale 2This close-up of Tisdale 2, the first rock Opportunity examined in detail on the rim of Endeavour crater,has textures and composition unlike any rock the rover has ever examined. Its characteristics are consistent with the rock being a breccia, a type of rock in which broken fragments of older rocks are fused together. Tisdale 2 is about 30 centimeters (12 inches) tall. The black vertical line that is superimposed on the image indicates the work plane for Opportunity's robotic arm when the arm placed its microscopic imager and alpha particle X-ray spectrometer at a series of locations from the top to the bottom of the boulder.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

So much zinc in fact it’s got the scientists giddily scratching their heads. “You call me a stoic Swede and I am totally excited,” offered Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis, the deputy principal investigator. “I'm even excited about the zinc," added the normally stoic planetary geologist who probably has logged more Mars miles than any other scientist. “This really is a brand new mission.”

"The trek to Endeavour Crater wasn't easy, nor was it straightforward," said John Callas, the MER project manager, recalling during the teleconference how Opportunity had to actually drive away from Endeavour at times to avoid potential rover trapping sand dunes dubbed "purgatoids."

It was, actually, was three years ago this week that Opportunity was climbing out of Victoria Crater, and not long after that the MER science team chose Endeavour as the rover’s long-term destination. “It's just amazing to be here after setting out almost three years ago,” Squyres told the MER Update. “To tell the truth, when we departed for Endeavour, I wasn't confident that we'd make it. But I wanted to pick a goal that was worthy of this project and this rover, and Endeavour was the obvious choice.”

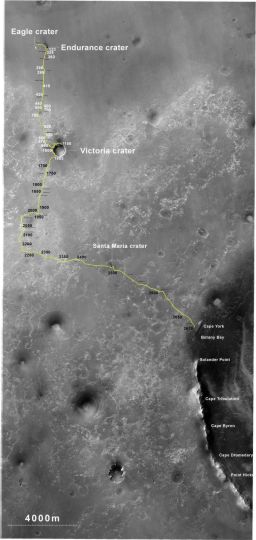

Opportunity's truly excellent road trip

Opportunity's truly excellent road tripThe yellow line on this map shows where Opportunity has driven from the place where it landed in January 2004 -- inside Eagle crater, at the upper left end of the track -- to a point approaching the rim of Endeavour Crater. The map traces the route through the rover's Sol 2670(July 29, 2011), its 2670th Martian day since landing.Credit: NASA / JPL - Caltech / MSSS / NMMNHS

Defying the odds again and showing her MER mettle, Opportunity pulled into the rim area of the 22-kilometer 14-mile wide Endeavour Crater on August 9, 2011. That's the day the robot field geologist completed what turned out to be a 21.5-kilometer (13.35-mile) journey from Victoria Crater by crossing the geologic boundary from the plains of Meridiani Planum into Spirit Point and the rock-strewn rim of Endeavour Crater.

The rover officially reached the southern tip of Cape York after a journey that took 1047 Martian days or nearly three Earth years. [Since landing at Eagle Crater in January 2004, the rover has driven 20.8 miles (33.5 kilometers).]

Veteran rover driver Frank Hartman, who has been with MER since the beginning, was, as luck and scheduling would have it, ‘at the wheel.’ “It's one of those events that allows you to look back and reflect a little,” he said during a recent interview. “It was nice for me to be able to do that drive, and plenty of people came in to tell me that. But the way I figure it, each and every team member contributed equally.”

Anyone involved with rovers or anyone who’s joined the rover expedition vicariously is likely to remember Landfall Day forever. To some it was an emotional moment. For others, it was a bit anti-climactic. But August 9, 2011 was anything but just another day on Mars. By all accounts, Opportunity’s arrival at Endeavour is an incredible achievement.

Endeavour Crater is a big deal not just because it’s the biggest hole in the ground the rover is likely to have the chance to study, but because of the evidence of the ancient environment that is harbored there.

The crater’s western rim exposes outcrops that hold clues of environments older than any Opportunity has roved upon, including parts of the Noachian crust from billions of years ago when meteorites and comets were regularly crashing into the planet and the land was dramatically eroding and valleys were forming, when volcanoes blew and winds weathered surface rocks and Mars was warmer and wetter at least part of the time.

Ragged or "discontinuous" ridges are all that remains of the ancient crater's rim today. The ridge at the section of the rim where Opportunity arrived is Cape York.

As Opportunity crossed the geologic boundary and began sending home breathtaking picture postcards of ragged boulders the likes of which it has never seen before, you could almost feel the electricity sparking from this team. The rover headed straight for a boulder field surrounding a smaller crater, named Odyssey, after the Mars Odyssey orbiter, and then spent more than two weeks checking out Tisdale 2. “It’s what a human field geologist would do,” explained Arvidson.

"Tisdale 2 measures about 1 meter (3 feet) across, and is about 30 centimeters high – and it is a breccia – formed with blocks of chunks of rock that have been fragmented and stuck together," as Squyres described it. Typically, breccia is found on the rims of impact craters, so finding breccia just outside of Odyssey Crater is consistent with the known planetary geology story. At the same time, while breccia is common on Earth, the MER scientists have not seen much breccia on this mission "and never before with Opportunity."

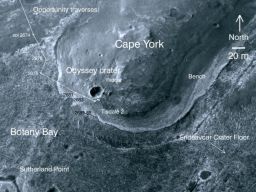

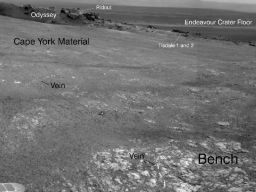

First neighborhood at Endeavour

First neighborhood at EndeavourThis image taken from orbit shows the path Opportunity drove in the weeks around the rover's arrival at the rim of Endeavour Crater. The sol or Martian days are indicated along the route. For example, Sol 2674 corresponds to Aug. 2, 2011; Sol 2688 corresponds to Aug. 16, 2011. The route leads to a rock dubbed Tisdale 2, a block of material ejected by an impact that excavated the small crater called Odyssey on an area of the Endeavour rim the team calls Cape York. The next Endeavour rim fragment to the south is called Sutherland Point, and a gap between Cape York and Sutherland Point is called Botany Bay. The base image of the map is a portion of an image taken by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) instrument onboard MRO, on July 23, 2010.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA

After analyzing the composition of Tisdale 2, the scientists were left with two take-away messages, Squyres said. "This rock doesn't look like anything else we've seen before. While some of its elements – silica, aluminum, chlorine – are similar – telling us it's a basaltic breccia, a piece of basalt that has been broken up, the details are different," he said.

“The other take away message is that Tisdale 2 has a huge amount of zinc in it,” Squyres continued. "We are puzzling over what that means. Rocks on Earth that are rich in zinc typically formed where there was some kind of thermal activity. This is a clue that we may be dealing with a hydrothermal system here, a situation where water has percolated as vapor or liquid through these rocks and raised the zinc level far in excess of what we have seen before. But we've only looked at one rock. Does zinc vary from rock to rock? Does it correlate with other elements? We don't know yet. There is more bedrock northeast – and we're driving further to the northeast and we will see what we see. Stay tuned, this is an interesting story we're working here."

The most conspicuous part of that interesting story still are the phyllosilicates that the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) detected along Endeavour’s rim last year. The orbital instrument picked up the faint signature of phyllosilicates, specifically iron-magnesium smectite clays, a family of clay minerals that form in a pH neutral water, in an area at Cape York, and a robust signal or “motherlode” of the stuff further south at Cape Tribulation.

Today, the rover left Tisdale 2 and is heading for the eastern flank of Cape York and more old bedrock and the area where CRISM detected that faint signature of smectite.

“Everybody is really excited and energized,” said Bruce Banerdt, of JPL, the MER project scientist, during a recent interview. “For three years it's been drive, drive, drive, and now suddenly we've got this incredible richness of targets to look at. There's so much information coming in to try and assimilate. It's like someone being lost in a desert for a week with one canteen and then getting dropped in the middle of a four-star restaurant. You hardly know what to do.”

Cape York

Cape YorkThis image, taken by the Hi-RISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows the rim of Endeavour and Cape York in natural Martian color, thanks to Stuart Atkinson's skillful image manipulation. "I joined together four different zoomed-in crops of the feature in order to give me one single, sharp image, but it was worth it," he says. Indeed.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / University of Arizona

Endeavour does offer a bounty of scientific riches. There's a kind of gap between Cape York and the next rim fragment to the south is known as Botany Bay, for example, that beckons with geologic goodies. "On the final traverses to Cape York, we saw ragged outcrops at Botany Bay unlike anything Opportunity has seen so far, and a bench around the edge of Cape York looks like sedimentary rock that's been cut and filled with veins of material possibly delivered by water," informed Arvidson. "We made an explicit decision to examine ancient rocks of Cape York first. But we took a lean or promise that on way back out of Cape York, we would go to other rim segments to look at that vein material as we head south through Botany Bay."

Beyond examining the ancient rocks at Cape York, finding the phyllosilicates is the best science “gold” Opportunity could send home. The smectite clay would unequivocally point to the potential for life, at least a possible past habitat in which lie could have emerged, and it would deliver what many will consider the mission’s greatest scientific achievement. It’s a huge lure and it's been something almost everyone on and around the team has been talking about. Even if the rover can't find smectite in Cape York, the “motherlode” awaits at Cape Tribulation and heading there next has been the buzz among both scientists and engineers. But there’s a rub -- rather, a hill to climb and that could be a challenge for the aging robot field geologist.

"Cape Tribulation has an extensive exposure mineralogically of smectite, which typically forms in presence of water sitting on basalt. But it's a couple kilometers to south and the rover would have to climb an 80-meter hill, and then drive down a 25 degree slope to get to it," Arvidson explained.

"We decided to go to Cape York first, because it has same geology and morphology," Arvidson continued. "And, there is the indication from CRISM for place we're driving to that there may be clay mineral signature, although it's very subtle."

Mission officials at the press teleconference today cautioned against the excitement burgeoning for Cape Tribulation, pointing to the reality that Opportunity is getting on in years. "We have a very senior rover in good health for having already worked 30 times longer than planned," said Callas. "However, at any time, we could lose a critical component on an essential rover system, and the mission would be over. Or, we might still be using this rover's capabilities beneficially for years.”

There is just no way of knowing how long Opportunity will keep going, nor is there any way of knowing if Mars will cooperate. "We're not driving a shiny new sports car anymore," said Dave Lavery, program executive for the mission at NASA Headquarters in Washington D.C., using a more familiar analogy. "We're driving a 1965 Mustang that hasn't been restored."

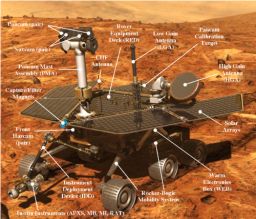

MER body parts

MER body partsThe Mars Exploration Rovers are robot field geologists that were designed with parts to substitute for the organs all living creatures would need to stay "alive" and able to explore, as well as some super-human powers. The rovers were designed with a body that protects its "vital organs;" brains to process information; temperature controls, including internal heaters, a layer of insulation, and more; a "neck and head" formed from a mast for the panoramic camera for a human-scale view; eyes and other "senses," such as cameras and instruments that give the rovers information about their environment; an arm to extend its reach; wheels and "legs," necessary parts for mobility; and energy sources in the form of batteries and solar panels; and antennas for "speaking" and "listening."

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

Despite the rover ’s ailments, from the "arthritic" shoulder joint down to a bit of "paralysis" in her neurological system to a steering loss on her right front wheel, Opportunity's "lithium ion batteries still retaining a good state of charge," said Callas, and "generally she's in good health sleeping well at night and her cholesterol levels are great."

For now, the rover’s future, all things considered, looks exceptionally bright.

Up on the Red Planet, the Martian summer is turning to fall and another brutal winter will follow. While the current amount of dust on Opportunity's solar arrays and in the skies overhead appear to be "trending up a little over past years,” the rover "should have enough energy to ride out the winter and beyond,” according to Callas.

“We've gotten to Endeavour and to the point where we can make new discoveries, so now we're in the business of making those discoveries,” Callas told the MER Update. “It really is like this is Sol 1 again for Opportunity.”

Opportunity is ready, willing, though her own handlers can't help but marvel, still very much able. “It's amazing,” noted Bill Nelson, chief of the rover engineering team. "With all the things this vehicle has done, she’s really had so few problems."

The newfound excitement can be heard in the voices of engineers and scientists alike as Opportunity cruises into a September that odds are will be one to remember. "We expected to find the unexpected," said Squyres. "It sounds a little silly, but you have to expect to find unexpected things when you go some place totally new. If you sat me down a month ago, and asked me to predict, and asked if we would find breccia, I would I have said, 'Yeah, probably.' Lots of zinc? Absolutely not. We've got some puzzles to figure out here."

Opportunity From Meridiani Planum

As August dawned at Meridiani Planum, Opportunity had less than 325 meters to go to get to Spirit Point, the area of first landfall at the southern tip of Cape York, located along the rim of Endeavour crater. The skies overhead were still typically hazy, but the rover was maintaining power levels above 375 watt-hours, plenty enough to do the driving she needed to do to complete the rover trek of a lifetime.

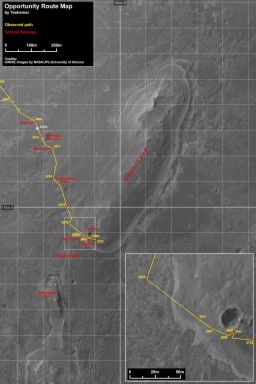

Opportunity route map

Opportunity route mapEduardo Tesheiner created this Opportunity route map from images taken by cameras onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. It shows the rover's travel to its Sol 2703 (Sep. 1, 2011).The rover officially reached the rim of Endeavour Crater on Aug. 9, 2011.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / MSSS / E.Tesheiner

Opportunity eased into August on Sol 2673 (August 1, 2011), taking care of routine engineering and science business, and using her autonomous AEGIS software to look for interesting outcrops.

The AEGIS software, on which the MER Update reported extensively in March 2010, was awarded the NASA 2011 Software of the Year Award. With driving in the next sol’s plan, Opportunity drifted off dreaming, no doubt, of Spirit Point.

Opportunity drove three times during the first week of the month, roving right up to Endeavour’s doorstep.

Beginning with a drive on Sol 2674 (August 2, 2011) the rover put 121.33 meters (398.06 feet) behind her, took a sol to rest, drove again on Sol 2676 (August 4, 2011) racking up another 120.77 meters (396.22 feet), and then logged another 75.26 meters (246.91 feet) on Sol 2678 (August 6, 2011).

As the first week of August came to an end, Endeavour was right there, the ragged edges of its rim and the rocks and debris that long ago it exhumed, just before here in glorious Martian color.

The next drive would likely put Opportunity over the boundary and “officially” at her destination, after nearlythree long Earth years. And, sure enough, some things are meant to be.

On Sol 2681 (August 9, 2011), Opportunity roved on for 62.21 meters (204.10 feet), crossing the boundary, the contact that delineates the geology of the rim of the giant crater from that of the plains. It was the final drive of what ultimately turned out to be a 21.5-kilometer (13.36-mile) cross plains trek of Meridiani Planum, bringing her odometer to 33.49 kilometers (20.81 miles). It was almost hard to believe the rover had finally made “landfall.”

“We had a good day,” summed up rover driver Hartman, who got up in the middle of the night to make sure everything went well. “We have an automated system that tells us when the rover gets to where it's going,” he explained. “The cell phone beeps it shows a little map of where it drove.I got up probably a half hour after the pictures came down, and already someone else had signed on and said: 'Yeah, we made it.’ This was an almost three-year journey from when we left Victoria Crater – that's a huge chunk of time,” he mused. “A lot of things happen in your life over that time.”

“There was a lot of excitement when this happened,” said Arvidson. “Unfortunately, the P.I. was in Svalbard doing his fieldwork.” But no matter where he is on planet Earth, Squyres is never far from his rovers, and courtesy an iridium satellite telephone he was checking in from the Arctic edge.

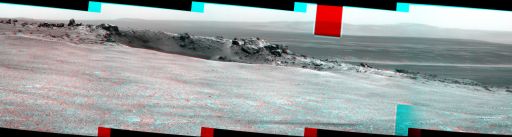

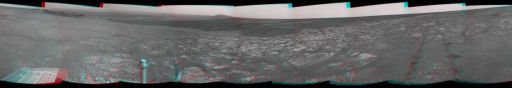

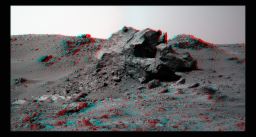

Spirit Point in 3-D

Spirit Point in 3-DThe 3-D view of where Opportunity first arrived in the rim zone of Endeavour Crater, an impact crater about 22 kilometers (14 miles) in diameter. The team dubbed the location of the rover's arrival Spirit Point, as a tribute to Opportunity's rover twin, which stopped communicating in March 2010 after more than six years of work on Mars. The view here encompasses nearly a full circle, from northeast at the left, around to straight north at the right. The small crater on Endeavour's rim near the left edge of the scene has been nicknamed Odyssey, as a tribute to the Mars Odyssey orbiter, which has served as the communications relay for nearly all of the data sent by both rovers since they landed on Mars in January 2004. View with red-blue glasses,red lens on the left.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

“It was pretty emotional,” agreed Banerdt. “We've seen the same Meridiani sandstones for kilometer after kilometer after kilometer, and suddenly we look ahead in the Pancams and there's a line beyond which there is something else -- and then finally you’re there, staring at that something else.”

In pockets of places, in towns and communities, and bustling metropolitan centers around the world, here and there, people very much aware that we Earthlings have a rover exploring on Mars took pause, if only to be moved. “There will be no astronauts on Mars for a long time,” wrote MER poet Stuart Atkinson, of UMSF.com, in his Road to Endeavour blog. “But there are people on Mars right now, today – an army of us, standing next to Opportunity as she prepares to make landfall at Spirit Point.”

For those 4000 individuals who contributed to the rovers, the hundreds who continue to work the mission, and all those unknown thousands, millions who have followed the adventures of the roving robot field geologists known as MER, it couldn’t have been put more beautifully. “Knowing that people are there and still supporting us with all of the things going on in the world -- that’s really neat,” said Hartman. “It makes a big difference to us to know people are following along.”

Looking ahead

Looking aheadBright veins cutting across outcrop in a section of Endeavour Crater's rim called Botany Bay are visible in the foreground and middle distance of this view assembled from images that Opportunity took with her navigation camera during the rover's Sol 2681 (Aug. 9, 2011. This was the same sol the rover crossed the geologc boundary from the Meridiani plains onto the rocky terrain of Endeavour's rim. The veins may have formed as minerals dissolved in ground water came out of solution and were deposited. A crater named after the Mars Odyssey orbiter, which is about 20 meters (66 feet) in diameter, is visible at upper right. It is on a low ridge called Cape York that forms part of the western rim of Endeavour Crater, which is about 14 miles (22 kilometers) in diameter. Rocks ejected by the impact that dug Odyssey are scattered on the ground to the right of Odyssey. One of these rocks, Tisdale 2, became the first rock that the rover has examined in detail. The scale bar is 20 meters (66 feet).Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

These are scientists and engineers we’re talking about however, and for some members of the MER team the long drives took their romantic toll and Opportunity’s arrival was a bit anti-climatic. Whatever one’s emotions, the achievement stands as undeniable.

“When you take a moment to think back to three years ago, it's – wow – we really did cover a lot of terrain,” Callas said. “We more than doubled the odometry on the rover, from 12 kilometers to 33.5 kilometers. We put 21.5 kilometers on between Victoria and Endeavour. Again, that's for this old rover. We were only required to go 600 meters by NASA,” he reminded. “We [raised] the NASA requirement by a factor of 50.”

The next chapter in the surface exploration of Mars begins now, and engineers and scientists alike are looking ever onward. “It really is a whole new mission,” Arvidson underscored.

For the engineers and rover drivers, it’s the opportunity to explore new, different terrain, undertake new challenges and see what else Opportunity may be able to do. For the scientists, it’s the opportunity to unravel more Martian mysteries, dig deeper in Mars past, and with a little of that MER luck the chance bring home the most significant scientific find on the whole mission -- clay minerals that may hold more evidentiary clues to an ancient, habitable environment in the early, wet Noachian Period of Mars.

The pace in the MER offices and the energy during the mission Science Operations Working Group (SOWG) meetings has picked up and the discussions have intensified. “We have scientists who have not been very active suddenly showing up and contacting us because their password had expired, and the number of people calling in to the meetings is now hitting saturation,” said Callas.

The science discussions have been “lively,” Banerdt reported. “It's really been a pretty difficult and intense discussion as to how much basic characterization we do versus going after the sort of high priority objectives we have here, which are to try to find the phyllosilicates that have been identified from orbit, really our Holy Grail right now of Noachian water involved minerals.”

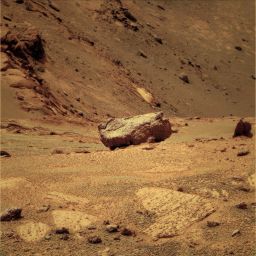

Odyssey Crater

Odyssey CraterOpportunity took this picture of Odyssey Crater earlier this month, shortly after the rover arrived at the humongous Endeavour Crater. Odyssey is a small impact that is located on the rim of Endeavour, and was named by the team in honor of the Mars Odyssey orbiter, which has been the rover's primary UHF radio communication link to Earth. Stuart Atkinson of UMSF.com rendered here in glorious Martian color. For more of Atkinson's images and writings about Opportunity's journey, see his blog Road to Endeavour at: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / S. Atkinson

While Endeavour has presented a dilemma of riches, the MER team has set its agenda, and Cape York is at the top of the list. “Everyone is onboard with the idea that we have set our priorities,” said Banerdt. “People get disappointed that we have to put our observations in the context of those priorities, but I think everyone seems to feel there's enough here for everybody.”

Mars must have been pleased with Opportunity’s arrival because at some point between Sols 2681 and 2683 (August 9 and August 11, 2011) it sent a modest gust of wind to clear some of the accumulated dust from the rove’rs solar arrays, bumping her energy levels to around 400 watt-hours.

The robot field geologist didn’t linger once she crossed into the new terrain. “We crossed Botany Bay and then crossed the bench that surrounds Cape York, then drove right onto the ejecta from Odyssey, which is a 20-meter crater that punctured into the Cape York materials,” Arvidson recounted. “We made a conscious decision to not stop, except overnight, until we got the ejecta deposit. The idea is let's get to Cape York sooner rather than later, because that's driving the whole extended mission to get to the ancient rocks and materials.” That doesn’t mean, however, that the rover won’t be coming back, he noted.

Ridout

RidoutOpportunity took this image of the boulder dubbed Ridout as it was checking out Odyssey Crater this month, shortly after arriving at Endeavour Crater on Aug. 9, 2011. Odyssey is a small crater on the rim of the 22-kilometer diameter Endeavour CraterCredit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell /color by S. Atkinson

Opportunity continues to warm up her wheels and do as much driving backwards as possible to mitigate the problematic current draw on the motor or actuator to the rover’s right front steering wheel. These mitigation techniques have worked well and continue to work, reported Nelson. “The right-front wheel currents remain behaved,” he said during an interview.

Odyssey Crater, named for Mars Odyssey, Opportunity’s primary UHF communications link, offered a treasure trove of rocks for the rover to behold. The largest boulder was one the team nicknamed Ridout. “It’s the biggest ejecta block associated with Odyssey, but it's right on the rim and we can't get to it, because it's way too rough,” explained Arvidson.

The MER science team members decided instead to check out one of another group of boulders dubbed the Tisdales, Arvidson said. The one they chose turned out to be a flat-topped boulder sporting “a kind of shiny red top.” Dubbed Tisdale 2, it was easily accessible for the rover. On Sols 2683 and 2685 (August 11 and 13, 2011), Opportunity performed a pair of drives -- 14.88 meters and 17.86 meters respectively -- to position herself for a close approach to the rock target.

As the second week of August turned to the third, Opportunity took care of routine engineering and science business, with the next scheduled drive – and approach to Tisdale 2 – to take place on her Sol 2688 (August 16, 2011).

Ridout in 3-D

Ridout in 3-DThis 3-D image of Ridout was produced from the rover's raw images by Stuart Atkinson, of UMSF.com, aka the MER poet. So get your blue/red glasses and walk in to take a closer look. Ridout is the largest boulder on the rim of Odyssey Crater, the tiny crater along the rim of Endeavour Crater that the rover checked out this month. For more of Atkinson's picture productions and poetry, go top his Road to Endeavour blog at: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / fx by S. Atkinson

On that sol, the rover moved .49 meters (1.60 feet), and then the drive stopped. Opportunity's visual odometry could not measure progress accurately because of a lack of visual features in her camera field of view and so the rover's system declared a "VISIDOM failure," said Nelson.

“VISIDOM is where we take pictures and compare the differences between the two to see how far and in what directions we've moved. When there are insufficient number of features to get a good correlation, the system faults, and it's said 'not to converge,' and it then declares a failure," Nelson explained.

"We started off with a turn to get ourselves pointed in the right direction, but the area we're looking at is relatively [featureless] sand," Nelson continued. "And it was during that turn that we failed the VISIDOM check. Since the failure occurred during a multi-sol plan, the 4-meter (13-foot) approach to Tisdale 2 was rescheduled."

On Sol 2690 (August 19, 2011), Opportunity completed the drive, but during her turn to face the boulder, VISIDOM failed to converge again, just after the first 15-degree step. "Our final turn at the end of the drive faulted out with another VISIDOM failure and it was of the same nature – namely that we turned and didn't have enough features for the camera to do its job," said Nelson.

True to her MER nature, Opportunity tried again. The third time was the charm, as they say, and on Sol 2692 (August 21, 2011), the rover achieved the 2.27-meter (7.44-foot) approach to Tisdale 2.

With all the interest in the phyllosilicates at Cape York, why did Opportunity take the time to stop and study Tisdale 2?

"It's what a field geologist would do,” explained Arvidson. “It's our kind of first taste of Cape York where the different rocks have been exposed. It's a good way to get the variation and composition and mineralogy of materials that make up Cape York, at least as far as Odyssey has excavated for us, which is probably a few meters. Besides that, Tisdale 2 had a kind of shiny top and just looked different.”

It would turn out to be a great decision.

The Tisdales

The TisdalesOpportunity took this picture of the Tisdales, a group of several boulders on the rim of Odyssey Crater and Stuart Atkinson produced it from the raw images sent down by the rover. Opportunity spent nearly three weeks checking out Tisdale 2 and found it to be unlike any rock this rover has seen before or anyone on the team has seen before. It is a type of breccia, a basaltic rock, but it is loaded with zinc, something of a mystery for the MER scientists. "Stay tuned," said P.I. Steve Squyres, "this is an interesting story we're working here."

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / S. Atkinson

On Sol 2694 (August 22, 2011), as the fourth week of August got underway, Opportunity started her close-up investigation of Tisdale 2 by taking a series of pictures of surface targets, collectively named Timmins, with her microscopic imager (MI). Then, the rover placed her alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) on a chosen spot for an overnight integration.

The next sol, Opportunity collected another series of pictures for an MI mosaic on a different target spot, and again followed it with an overnight APXS integration. And on Sol 2696 (August 24, 2011), repeated the process on another spot all to analyze the boulder's composition.

Opportunity continued checking out the composition of Tisdale 2 through last weekend and into Monday of this week. "We wanted to do transects top to bottom,” said Arvidson. “This boulder is breccia, different rock fragments and glass either put together during the original Endeavour impact or the Odyssey impact," said. "It's about 1.4 meters long and maybe 30 centimeters high and has all sorts of goodies in it."

Breccia is "a term most often used for clastic sedimentary rocks that are composed of large angular fragments (over two millimeters in diameter)," according to Geology.com "The spaces between the large angular fragments can be filled with a matrix of smaller particles or a mineral cement that binds the rock together. Breccia forms where broken, angular fragments of rock or mineral debris accumulate. One possible location for breccia formation is at the base of an outcrop where mechanical weathering debris accumulates. Another would be in stream deposits near the outcrop such as an alluvial fan. Some breccias form as debris flow deposits. After deposition the fragments are bound together by a mineral cement or by a matrix of smaller particles that fills the spaces between the fragments."

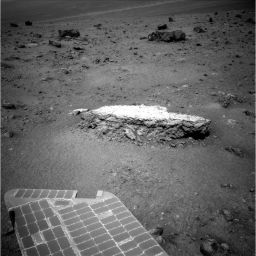

Approaching Tisdale 2

Approaching Tisdale 2Opportunity used her navigation camera to take this picture on her Sol 2690 (Aug. 18, 2011). It shows the flat-topped rock, Tisdale 2, that the rover spent a couple of weeks this month checking out up close. "This is different than any rock seen on Mars," said principal investigator Steve Squyres. The rock is about 12 inches (30 centimeters) tall. This rock and others on the ground beyond it were apparently ejected by the impact that excavated a 20-meter-wide (66-foot-wide) Odyssey Crater, which is nearby to the left (north) of this scene. Odyssey and these rocks are actually on a low ridge called Cape York, which is a segment (edge) of the western rim of the 22-km-diameter crater Endeavour. Confused? Check out the other maps in this Update.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

“Chemically, Tisdale 2 not like anything we've seen before,” said Arvidson. “It's got a lot of interesting materials like zinc, and bromine. Other than that, we're not quite sure what's going on, but the three measurements we've gotten down [from the spacecraft, a fourth is still onboard] are different than one another. It's still a basaltic class rock. We're after the type of alternation and that's going to take a while. These are species that are dissolvable in water though, so I think we're getting close to what we wanted to do – look at the ancient water-related processes.”

"Tisdale 2 is raising a lot of questions – about how old these rocks are, what the processes that formed them, how common they are across Mars?" said Banerdt. “We could probably spend months at this rock, but we're trying to get a bunch of characterization measurements on it as quickly as we can, and then we're going to head on to Cape York and start looking for the phyllosilicates.”

On Sol 2697 (August 25, 2011), Opportunity repositioned herself by doing a bump forward of about .15 meters (5.9 inches) to better position her instrument deployment device (IDD) or robotic arm for placing the scientific instruments on another chosen spot on the top of the boulder, reported Nelson. "In the past when the arm has been stretched out really far, we've had it fault out, so we would prefer not to have that happen. This bump forward allowed us to not to have to extend it out so far.”

Last Sunday, the rover's Sol 2700, the team decided to have the rover conduct another set of diagnostics on the miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES) that began acting up last year and hasn't been working since. "We’re all about trying to exhaust even remotely likely possibilities," noted Nelson. Opportunity followed her commands to exercise the back-up laser and back-up optical switch.

“We've also been using the Pancam – 13 filter – to look around at other boulders," said Arvidson. "It looks like Tisdale 2 is pretty representative of the other boulders in the ejecta field and so we'll probably drive north/northeast through or around the boulder field and toward the ancient rocks at Cape York that we hope have the phyllosilicates. It's a very subtle signature [of smectite] from CRISM at Cape York,” pointed out Arvidson, who is also a co-investigator on that instrument, which is onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. But that’s not going to stop this rover or this team.

With her work at Tisdale 2 declared done, Opportunity drove on today, her Sol 2703, toward the eastern flank of Cape York. She drew an arc backwards, turning about 180 degrees, then drove straight backwards for about 20 meters. “The path of the drive looks like a candy cane with the loop at the west and the long part below (south of) the start,” Nelson elaborated. It is essentially a drive east and a setup for the next plan (Sols 2706-2708) to be carried out this weekend.

Due to the combination of the Labor Day holiday weekend and the Grail launch to the Moon, set to launch September 8th from Florida's Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, MER will probably lose some of its communication passes with Odyssey and the Deep Space Network (DSN). To compensate and keep Opportunity working, the team is sending up “several long plans in a row to tide us over,” said Nelson.

Follow the zinc

Follow the zincOpportunity is setting off on a new adventure that Stuart Atkinson has summed up in a tour poster... just for the fun of it. Credit: NASA /JPL / Cornell / art by S. Atkinson

Opportunity’s next immediate destination is an outcrop on the southern brow of Cape York, located, as Nelson described it, "roughly 30 meters (98.42 feet) north of Spirit Point or the area of the southern tip of Cape York, and roughly 45 to 50 meters (131.23 to 164.04 feet) east of Tisdale 2."

Depending on the what Opportunity finds when she gets there, the science team will likely decide to really dig into this distinctive bedrock. “Once we find bedrock, we'll look at it once again, we can use the RAT, which we didn't use on Tisdale 2 because the rock was too bulky,” said Squyres.

Spirit Point has given the rover drivers and Opportunity a chance to get “a feel” for the new terrain, Hartman said. “The nice thing for us is Spirit Point is different and rocky. But it's not too steep, although we are already experiencing 10,11, 12-degree tilts, which is far beyond what we've found on the plains. Since it's certainly steeper than we're used to, it lets us get our 'legs' a bit, see what the terrain is like, and how we respond when we drive on it. Hopefully it’s going to serve as [transitional] area where we can get ourselves acclimated to the region," he said.

The rover drivers are taking it all in, looking around in every direction, while Opportunity is still roving in a relatively flat area, Hartman added. "The plan beyond is to really look at those hills to the south – that's real mountain climbing," said Hartman. "Cape York is much more manageable, more weathered, more eroded, and there are some indications phyllosilicates are here, so we're going to sniff around here and see if we can find them, but the longer-term plan is to attack Cape Tribulation. That's going to be a whole other kettle of fish for us.”

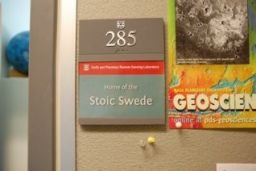

Ray Arvidson's office door

Ray Arvidson's office doorJust for anyone listening in on the press teleconference and who may be doubting the accuracy of the MER Update's reportage, this is an image of MER Deputy P.I. Ray Arvidson's office door at Washington University St. Louis. For the record, to say he is excited about Opportunity's new environs is, in fact, a true statement.

Credit: Anonymous

As ready as they are to take on those hills to the south, the MER leaders are talking more cautiously. “We still have to have the discipline because we always have to think – what if this was the last thing we got to do?” said Banderdt. “You never know when something's going to happen so there's still an impetus to keep moving in the sense of keep the highest science priorities in front of us.”

Even as Opportunity heads to Cape York, once the rover's work is done there – and right now there's no reason to believe it won't finish the work in fine form – how could this team possibly consider not going to Cape Tribulation?

"It's amazing to be here after setting out almost three years ago,” Steve Squyres told the MER Update yesterday. “To tell the truth, when we departed for Endeavour, I wasn't confident that we'd make it. But I wanted to pick a goal that was worthy of this project and this rover, and Endeavour was the obvious choice. Now we've made it, and it feels like a new mission all over again," he reiterated.

"We don't know how long it's going to take us to solve all the different scientific puzzles that have been posed just by the stuff we've already found at Cape York,” Squyres continued during the teleconference. “Having said that, Cape Tribulation is the obvious next place to go for after we've really done our job at Cape York. So we're going to do the best that we can here. Then we're going to see what kind of a rover we've got and we're going to do the best we can with it. Are we going to Cape Tribulation or not? Don't know. I hope so. It looks pretty cool."

The trip, however, is already being envisioned. “When we leave Cape York, we'll probably head south," said a confident Arvidson, “and we'll catch the things we wanted to get to at Botany as we drive across it heading south to Sutherland Point, Knobby's Head, Solander Point, and Cape Tribulation …”

Onward Opportunity.

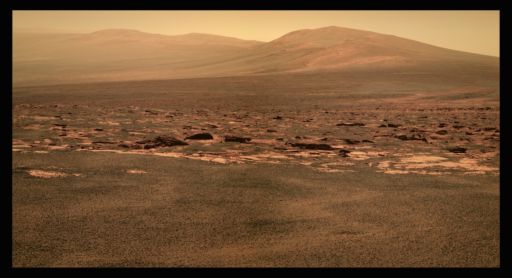

Cape Tribulation

Cape TribulationOpportunity took the pictures that went into this image of the Tribulation range with her panoramic camera (Pancam) just before crossing the geologic boundary and pulling into Spirit Point earlier this month. Stuart Atkinson, of UMSF.com and MER poet, produced it here in color. After nearly three Earth years on the road, the rover officially completed the journey from Victoria Crater to Endeavour Crater on Aug. 9, 2011. Orbital data acquired from CRISM onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter indicates there are deposits of phyllosilicates to be found around Endeavour and the Motherlode is in these hills. For more of Atkinson's images and writings about Opportunity's journey, see his blog Road to Endeavour at: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / color by Stuart Atkinson

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth