Jason Callahan • Aug 29, 2014

The Rise and Fall (and Rise and Fall) of Planetary Exploration Funding

NASA has explored the planets since the 1960s, but funding has rarely been consistent

Having looked at NASA’s place in the federal budget, I want to focus now on the role of space science generally and planetary science specifically at NASA. How does space science fit into NASA’s goals, and how has that changed since the agency’s formation? What are the effects of placing a high priority on planetary exploration (or not, as the case may be)?

NASA and its Priorities

When Congress and the Eisenhower Administration first established NASA with the National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958, they provided the new agency with eight separate objectives. I think it is very important to note that the first objective listed states that NASA will contribute to, “[t]he expansion of human knowledge of phenomena in the atmosphere and space.” To my mind, this places science at the top of NASA’s list of priorities.

One of the clearest indications of an organization’s priorities is the level to which they fund their programs. So, looking at changes in funding levels serves as a good indicator of changing priorities.

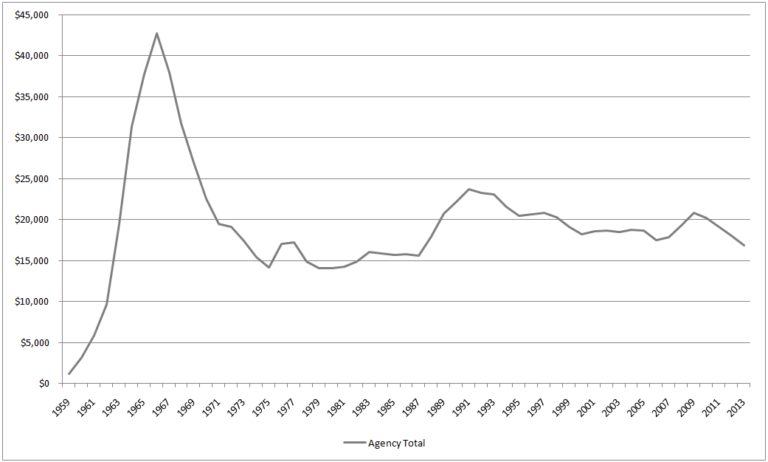

The above plot shows NASA’s top-level funding over the last five decades. The most apparent feature of Figure I is the spike in NASA’s funding during the 1960s, which coincides with the race to the Moon. The Moon race was not simply NASA’s top priority, it was a national priority, which is precisely what accounts for the massive investment.

Notice that the funds for the Moon race peaked in 1966, three years before the Apollo 11 landing. One major feature of large aerospace budgets is that development costs are far higher than operations costs, so the effects budget increases or reductions aren’t usually evident to outside observers for a few years. It can take a team of hundreds or even thousands of people years to build a spacecraft, but once it has launched, a crew of a few dozen people can often operate it. One of the dangers for the sustainability of NASA programs is the perception that, when the agency’s budget is reduced, things seem to still be going well for a few years, since projects in development are given priority over starting new projects. Today's missions were paid for by previous years' budgets. Today’s budgets are paying for tomorrow’s missions. Cuts now irreparably hurt the future of exploration.

The other major increase in NASA’s total budget occurred in the late 1980s, following the Challenger disaster. This was a national tragedy, and building a new shuttle became a national priority, not just a NASA priority.

These two anomalous instances (the Moon race and rebuilding after the loss of Challenger) notwithstanding, NASA’s budget has remained fairly steady over the years, bounded between $13 billion and $20 billion per year. Granted, there is a huge difference between those sums, but they seem to be the rough boundaries of federal investment in NASA, barring circumstances outside of the agency’s control.

As a testament to the unusual nature of these two events, we should note that the budget following the Columbia tragedy in 2003 did not increase as dramatically as it did after Challenger. Congress and the White House did not view construction of a replacement shuttle as a national priority, nor did they invest at a commensurate rate to replace the shuttle program (leading, eventually, to the cancellation of the Constellation program, which is another story).

Is Space Science a Priority?

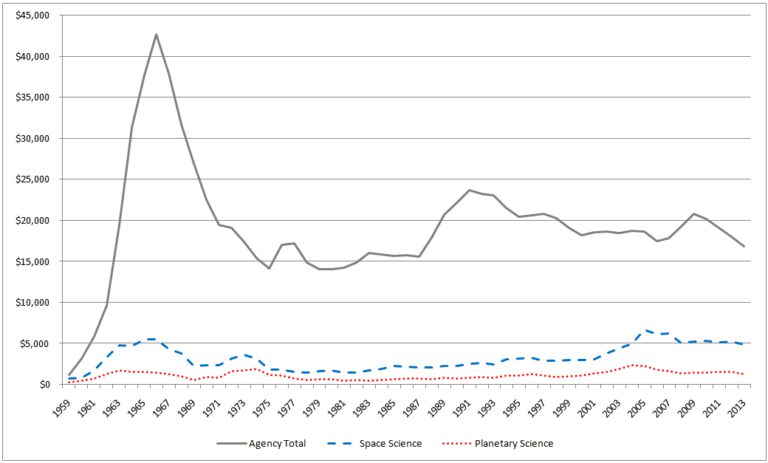

Here we see NASA’s top-level funding over the last five decades in grey, with space science funding in blue. So, the space between the grey and blue lines covers all of NASA’s activities outside of space science, including aeronautics research (the first A in NASA), technology development, education, center and agency management, construction, maintenance, and the entire human spaceflight program.

The total space science budget has rarely exceeded $5 billion, and has averaged just over half that amount. Remember that space science is more than just planetary: astrophysics, heliophysics, and Earth science are all funded in this number.

Despite this, space science accounts for an average of 17 percent of NASA’s total budget, though it has significant fluctuations. In the 1980s, space science was a mere 11 ½ percent of NASA’s budget, but in the 2000s, it made up 27 percent. As a quick glance at the above plot shows us, space science has not always been a priority at NASA, but it has certainly gained traction in the last decade.

The Rises and Falls of Planetary Science

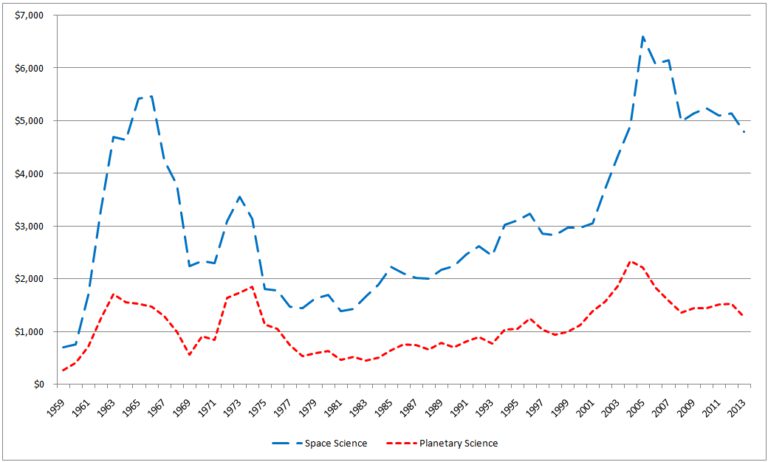

In NASA’s first decade, many space science efforts were attached to the human spaceflight program, primarily in trying to determine the nature of the space environment to aid in future human missions, and then flying robotic lunar missions to test technologies and map the Moon. Despite the focus on the Moon program, NASA scientists and engineers also began developing the earliest planetary missions with the Mariner program. From 1960 to 1969, planetary science made up 32 percent of the space science budget, but only five percent of NASA’s total budget.

As the Apollo program came to a close in the 1970s, many space scientists felt that NASA could finally get back to its primary purpose—scientific exploration—and they argued vigorously for a stronger science program. As we can see, their argument prevailed for a time. Planetary science became the dominant portion of the space science budget, and from 1970 to 1979, planetary science accounted for nearly 50 percent of the space science budget, but still only six percent of the total NASA budget. In this decade, NASA launched the Viking mission to Mars and the Pioneer and Voyager missions to the outer planets (and beyond).

The 1980s brought about an existential crisis for U.S. planetary exploration. As we see above, NASA’s planetary science budget was cut to the bone and the entire enterprise was nearly abandoned. NASA was able to develop and launch the Galileo spacecraft in the 1980s, demonstrating that large projects may be viable even at historically low funding levels, but Galileo faced a tremendous amount of budgetary adversity. And like a snake that swallowed a goat, the planetary science community had to wait for Galileo to pass through before new missions could begin. In fact, NASA launched only one other planetary science mission in the 1980s (Magellan), resulting in a “lost decade” of planetary exploration. The volume of talent and capability abandoned to attrition during this time is difficult to measure. Planetary science made up 32 percent of a depleted space science budget in this lost decade, but just three percent of a historically low NASA budget, reflecting the priority NASA leadership and lawmakers placed on scientific exploration of the solar system.

By the second half of the 1990s, planetary science experienced a moderate increase in funding, resulting in an increased flight rate for new missions. A new generation of space enthusiasts marveled at the first photographs from Mars in more than a decade as NASA distributed video from the Mars Pathfinder’s rover Sojourner over an increasingly popular internet. Pathfinder was the first mission of the incredibly successful Discovery program, focused on small planetary missions. NASA also launched the flagship mission Cassini, which became the first spacecraft to orbit Saturn and is still operating today. During the 1990s, planetary science represented 33 percent of the space science budget, and 4 ½ percent of NASA’s total budget.

While many have referred to the ‘60s and ‘70s as the “Golden Age” of planetary exploration, I think a case could be made that the real golden age began in the first decade of this century. Looking again at the plot above, we see that NASA’s planetary science budget hit its highest level historically in 2005, and the list of successful missions since then is impressive. A fleet of spacecraft went to Mars to orbit, land, and rove on the planet, providing an unparalleled scientific return. MESSENGER became the first spacecraft to orbit Mercury, and New Horizons, launched in 2006, will arrive at Pluto next year, the first spacecraft to visit the dwarf planet. From 2000 to 2009, NASA’s Planetary Science Division received 34 percent of the agency’s increasing space science budget and nine percent of NASA’s total budget.

So clearly, prioritization (as demonstrated by funding) has real consequences. And more, there seems to be a floor to the level of funding we can allocate to planetary science and still maintain a viable program (the early 1980s). By contrast, we have seen the effects of a moderate prioritization (the 1990s) and a higher prioritization (the mid-2000s). In my next post I hope to dig a bit deeper into just what we get for our investment in planetary science.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth