Emily Lakdawalla • Aug 28, 2012

An unheralded anniversary

Yesterday, August 27th, 2012, was, in a sense, the 50th anniversary of interplanetary travel. Fifty years ago yesterday, Mariner 2 launched toward Venus, and became the first object to leave Earth and travel to another world. By means of robot avatars, humans have been interplanetary travelers for half a century. For me, this anniversary is a big deal, insofar as round-number anniversaries mean anything, but I've hardly seen a mention of it except for a few Tweets.

There were places where I could have noted this date and planned ahead for it, but, for whatever reason, I didn't notice. There are lots of anniversaries being noted and celebrated these days, the most celebrated one this year being the 50th anniversary in February of John Glenn's circling the Earth in Friendship 7.

Mariner 2 was not a sexy mission, so it's not surprising it's relatively obscure. It didn't carry a camera. Its science experiments were, by modern standards, pretty rudimentary, but there was an impressive number of them. It had a cosmic ray detector and a cosmic dust detector. It had a solar plasma spectrometer, a microwave radiometer, and an infrared radiometer. But by visiting Venus, it learned a number of basic facts about the planet about which we'd been ignorant until the encounter. According to the National Space Science Data Center:

Scientific discoveries made by Mariner 2 included a slow retrograde rotation rate for Venus, hot surface temperatures and high surface pressures, a predominantly carbon dioxide atmosphere, continuous cloud cover with a top altitude of about 60 km, and no detectable magnetic field. It was also shown that in interplanetary space the solar wind streams continuously and the cosmic dust density is much lower than the near-Earth region. Improved estimates of Venus' mass and the value of the astronomical unit were made.

All of the facts in that paragraph are pretty much all the basic facts that you'll learn about Venus in anything other than a college-level textbook. For me -- someone who's never known a time when there weren't interplanetary spacecraft -- I am struck by how ignorant we were about our nearest neighbors in the universe, before we began visiting them with robots, fifty years ago yesterday.

Before Mariner 2, everything in the universe was an astronomical object. After Mariner 2, we had turned one of those points of shimmering light into a world -- a world with atmosphere, climate, and weather, like ours. Yet it was also a world whose most basic physical properties -- like how fast it rotates -- were utterly alien to our own. When Mariner 2 visited Venus, not only did we learn about our neighbor planet, but the possibilities of things we could imagine finding at other planets became both more specific and more varied.

We still have not managed to send humans to any of these worlds beyond the Moon. The death of Neil Armstrong last weekend is poignant, because although he didn't talk about it very much, Armstrong clearly hated the idea that he and his fellow Apollo astronauts would be not just the first but also the last astronauts to visit the Moon. As much of a fan as I am of robotic exploration, I am not going to argue that robotic exploration replaces or competes with the desire that many of you share with Armstrong, to see humanity become a spacefaring species.

But robots can -- and do, every day, these days -- go to places that no human now living could ever hope to go. Into the acid-washed inferno of Venus' hellish atmosphere. Flying among the glittering icy moons and rings of Saturn. And they've been doing that for fifty years, serving as our eyes, ears, and organs of other senses that humans don't even have.

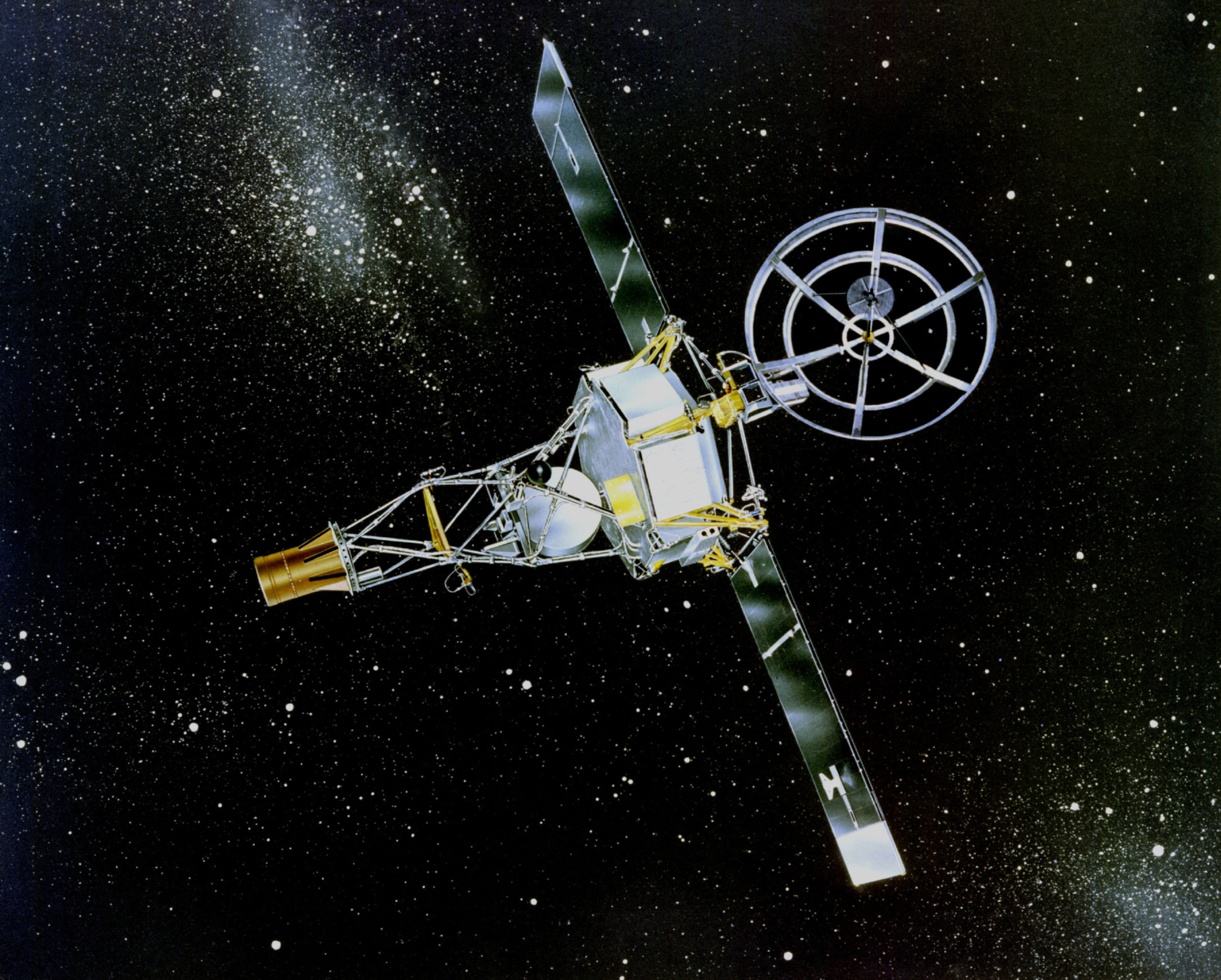

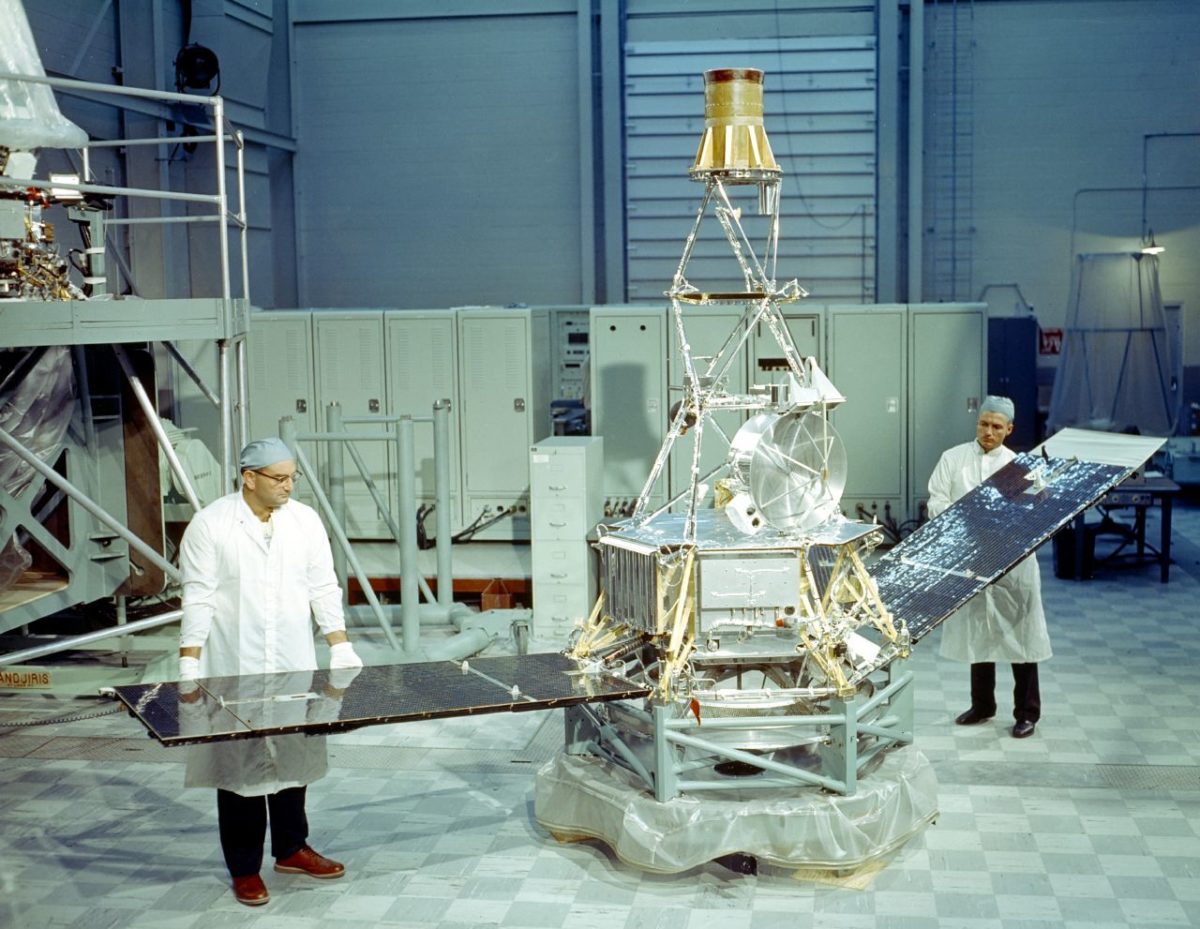

There weren't many images of Mariner 2 available online, so I tried calling JPL media and got connected to an archivist who was able to supply me with a couple from their collection. (Very quickly, too!) Here's one of Mariner 2 during final pre-launch preparations, to give a sense of scale. Although it's considerably taller than the two men in the photo, there's not a lot to it; take off the solar panels and the skeletal science instrument mast and it's a petite little thing, a bus only a meter across and a third of a meter thick.

But here's the best photo I came across in my searching: A replica of Mariner 2 and Venus in the Pasadena Tournament of Roses Parade, January 1, 1963. The Grand Marshal of the parade was JPL's director, William Pickering. A lot has changed in fifty years, but Pasadena still decks out cars in fantastical floral sculptures every New Year. I hope someone puts a flower-bedecked Curiosity rover on their float this year!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth