A.J.S. Rayl • Aug 01, 2018

The Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Dust Storm Wanes, Opportunity Sleeps, Team Prepares Recovery Strategy

Sols 5133–5162

Opportunity may be seeing the light again, a little sunlight that is.

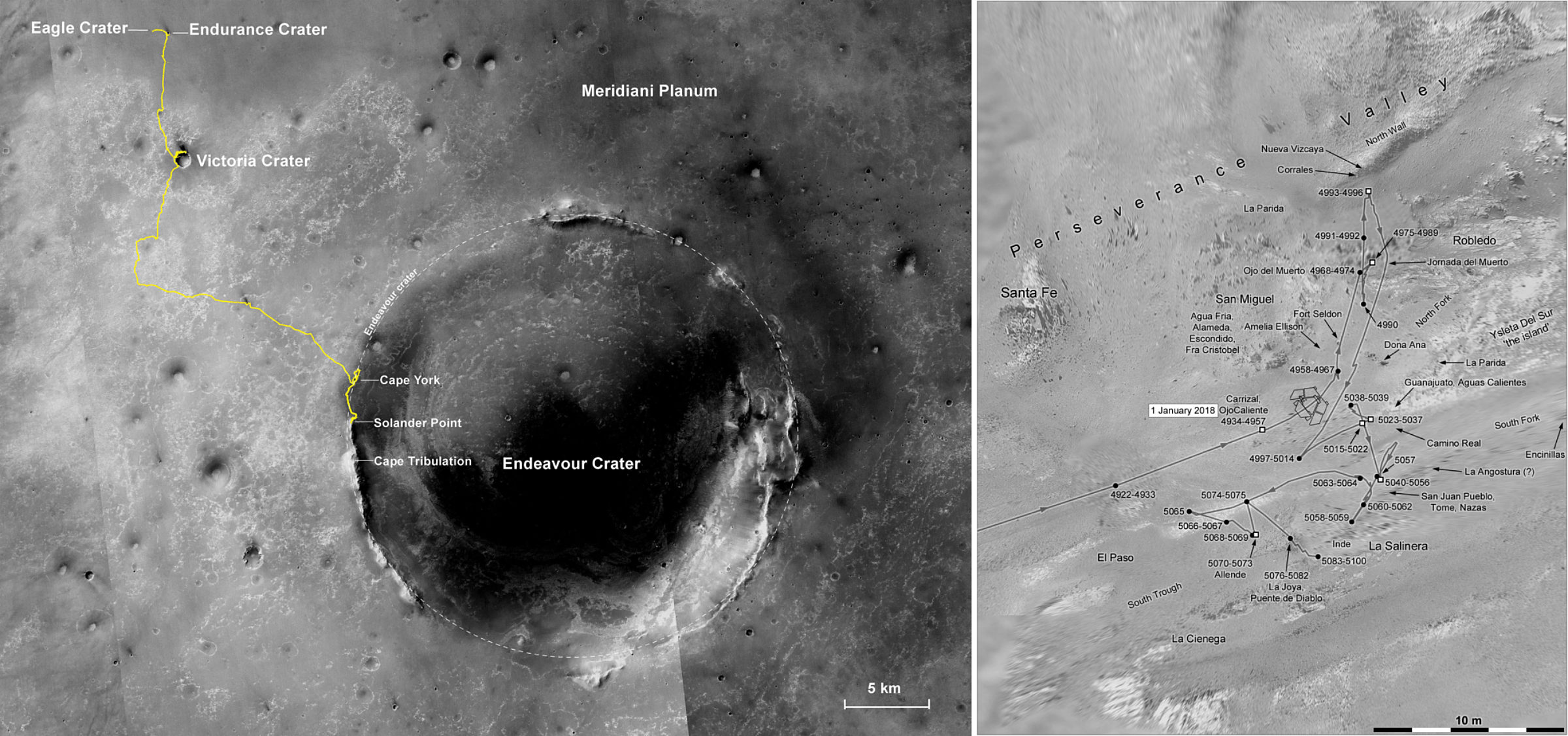

As the veteran Mars Exploration Rover (MER) slept in Endeavour Crater’s Perseverance Valley under the thick cloud of dust that has blanketed the Red Planet for the last six weeks, scientists who are studying the monster storm that forced the robot field geologist into its hibernation mode are now reporting the tempest has peaked.

“We’re pretty confident this storm is now in its decay phase, because the metrics are all pointing in the same direction: we’re starting to see surface features in more places; the middle atmosphere is starting to cool down a bit; and the dust lifting centers seem to be petering out,” said Richard Zurek, Chief Scientist of the Mars Program Office at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the birthplace of all NASA’s Mars rovers and orbiters.

“What this means is that more dust is falling out of the atmosphere than is being raised into it,”elaborated Zurek, who is also Project Scientist of the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) mission, which has instrument teams researching and documenting various aspects of this storm.

It was great news and the MER team welcomed it enthusiastically. While the dust haze is still widespread, “Opportunity may be getting some energy from the Sun now,” said MER Project Manager John Callas, of JPL.

Huge dust storms like this one are actually mergers of smaller storms and they are rare. In fact, these monster storms only appear every three to four Mars years (about six to eight Earth years) on average, luring and challenging today’s atmospheric scientists to figure out how and why local dust squalls turn regional and then grow to engulf the planet.

These planet-encirclers are also highly dynamic, wildly unpredictable, and taunting. The atmosphere above any given area, for example, may clear for a bit and then get dusty again, depending on the intensity of activity nearby, and which way and how strongly the wind is gusting. For now, you really do need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows on Mars.

The MER team, as well as the entire Red Planet community, has been keeping a close eye on the global maps and movies produced by one of the most prominent Mars weathermen, Bruce Cantor, of Malin Space Science Systems, who has been studying the meteorological conditions there for more than 20 years. Using data and imagery taken by the Mars Color Imager (MARCI), which currently offers the best view of the planet from its perch onboard MRO, he produces a weekly Mars Weather Report on which Opportunity and Curiosity, the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) rover, rely.

The Planet-Encircling Dust Events (PEDEs), as Cantor defined these massive storms, churn up dust from the Martian terrain high into the atmosphere, “in excess of 60 kilometers,” he said. That’s more than 37 miles or seven times higher than the 30,000-foot altitude at which most large passenger jets fly, making for one super-thick, doorstep-darkening, fear-inducing cloud.

Consider that Mars has a much thinner atmosphere than Earth. A typical local-size storm on Mars reaches “10-15 kilometers” (about 6-9 miles) in height, Cantor said, while the recent haboob in the Phoenix, Arizona area on Earth reached “about 1.5-1.6 kilometers” (just under a mile) in height in early July. There’s just no comparison to a PEDE.

Last week though, Cantor saw signs indicating that the storm is beginning to dissipate. First, he found breaks in the veil of dust obscuring the planet that allowed him to see surface features that have been buried under the haze for six weeks. Then, by employing a measurement system that Mars scientists use to determine the atmospheric opacity, a parameter that indicates the amount of dust in the atmosphere, he assessed that the cloud is indeed thinning, and his latest Mars Weather Report was sunnier than it has been since May.

This dust opacity measurement, called a “Tau” in Mars science jargon, allows scientists to gauge and monitor dust in the atmosphere from both the Martian ground and from orbit. Acquiring a Tau measurement from the ground is preferred for surface missions, because rovers and landers are, after all, on Martian terrain, it is more accurate locally, and in the case of Opportunity because the local dust scene is what matters most to this solar-powered rover’s ability to live long and prosper.

Opportunity takes this measurement daily as part of her normal routine, using the Sun as the point of reference, which, of course, is a known, steady magnitude light source. Over the 14 years and six months of this mission, MER Athena Science Team member and atmospheric scientist Mark Lemmon, Senior Research Scientist of the Space Science Institute (SSI), who also works on the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) rover Curiosity, has used this method to consistently determine what the dust opacity or Tau, which in turn helps the team estimate how much sunlight is getting through to the arrays.

But when the storm blotted out the Sun at Endeavour Crater and sent Opportunity into sleep mode, taking an atmospheric opacity measurement at Endeavour Crater was impossible. In the communiqué the MER team received from Opportunity on June 11th, the rover reported a Tau of 10.8, “the largest ever recorded on the surface of the Red Planet,” noted Mission Manager Scott Lever, of JPL. When the team did not hear from the rover on the next communication pass, Callas declared spacecraft emergency, because that level of opacity essentially meant the sky over the rover was near pitch black.

In fact, the jaw-dropping measurement overtook the record held by the Viking landers, which estimated a Tau of 9 during a PEDE back in the late 1970s; thus, it chalked up another record for MER, albeit one that was not desired.

Estimating the Tau from orbit is tricky, but it is possible. By using a terrestrial model tuned for the Martian atmosphere by colleague and MARCI science team member, Michael Wolff at the Space Science Institute, a model that he has used during the last 20 years, Cantor crunched the numbers based on the MARCI data in late July and produced a calculated estimate of a Tau that put guarded smiles on the faces of MER team members: the dust opacity at Endeavour had dropped substantially, to approximately 3.6 with a margin of error of 1, meaning the haze could be as low as 2.6 or as high as 4.6, “a huge uncertainty,” he admitted.

Although those numbers lifted MER spirits, anything over a Tau of 1 can be troubling, and so each of those numbers is still high enough for everyone on the team to remain concerned and focused.

But lower is better than higher. And, as MER Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis, put it: “It could be worse.”

The MER team is keenly aware this PEDE is not over and that they have a ways to go before the Opportunity may emerge from the darkness. “Even though the storm may be entering its decay phase, past experience with major storms suggests that it will still be weeks before skies will have cleared enough over Meridiani that hearing from the rover might be possible,” said MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres, of Cornell University. “So for now we're exactly where we have been...waiting.”

The MER ops team, however, isn’t sitting around as they wait, but rather working even harder, if that’s possible. The team officials are hard at work putting together a plan to recover the rover when Opportunity phones home, assuming, of course, that she does, and other team members are contributing to that process in whatever ways they can.

The ops engineers, for example, continue to build strategic communication windows for the orbiters, even though they won’t be used until Oppy phones home. “We’re still building communications windows for nominal uplinks and downlinks so that when we do resume we’re ready to jump in,” explained Lever.

Given the blinding circumstances of a PEDE, there is just no way of knowing what state Opportunity will be in once contact is made, so every possible scenario and issue is being considered. “It’s helping to keep morale up,” said Chief of MER Engineering Bill Nelson, of JPL. “And with the news that the storm appears to be on the wane, people are getting pretty optimistic that we are going to hear from the rover.”

“There are many avenues to consider, but just getting data from Opportunity is going to be key,” Lever underscored. “We need to hear from Opportunity before we can do anything.”

Despite all the uncertainty, hope still floats on MER.

In the midst of the haze, there has been some good news. On June 28th, the team got a letter from NASA HQ informing that the MER mission was granted its proposed one-year extension for the next fiscal year, informed Callas. “All of our operating missions were extended for one year because based on a recommendation from one of the National Science Academies committees, NASA is moving to a 3-year proposal cycle for the extended missions,” Zurek added.

About a year from now, if everything goes well, MER officials will be submitting a proposal for its 12th mission extension. “I hope they will still be plugging away, down there on the floor of Endeavour Crater, working their way around the inner part of the rim,” Zurek said.

“Even though we have no way of knowing how Opportunity is doing, I genuinely believe, as most everyone does, that we’re going to make it through this and that we’ll be talking to our rover again in a little while,” said JPL Rover Planner Ashley Stroupe. “We just don’t know when.”

As July came to an end, Mars' orbit brought it closer to Earth than it has been since August 2003. The Planetary Society celebrated that 2003 close approach by throwing a birthday party for beloved Martian Chronicles author, friend, and supporter Ray Bradbury and viewing that approach through the 60-inch telescope at Mount Wilson.

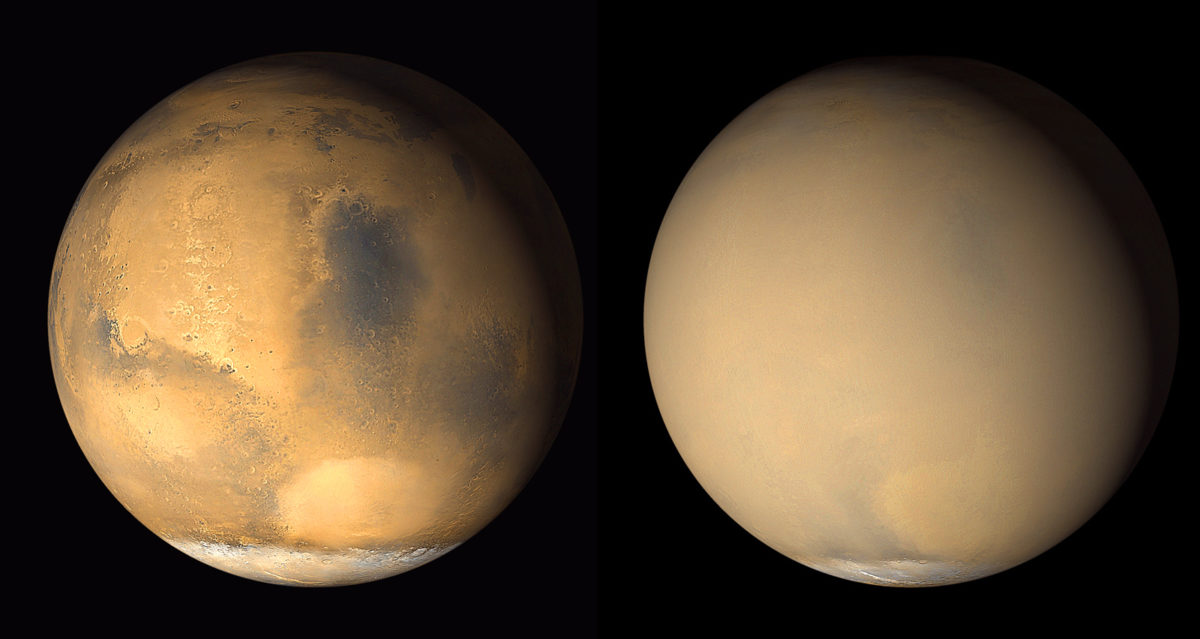

This year, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope photographed the Red Planet and despite the dust storm, there were some large surface features visible. It was, as Mars always is, a sight to see.

This storm, the worst the MER mission has experienced in 14.7 years of roving Mars, caught the team by surprise. “Given the humble beginnings of this storm, we never thought initially that it had a chance of becoming this bad,” said Stroupe. “Certainly we have seen this kind of intense storm in orbital imagery from Earth before, but none of them had hit one of our assets like this one did.”

Opportunity did survive a PEDE hit in 2007, but the dust lifting centers weren’t as close as they were this time around. “And we didn’t shut down entirely,” Stroupe reminded. “We went a few days without talking with her, but the rover stayed in sequence control, even when we commanded her to sleep.”

Like the wildfires raging in California right now, PEDEs on Mars don’t discriminate. Over on the other side of the planet, the nuclear-powered Mars Science Laboratory, Curiosity, has been able to continue working in Gale Crater. “We haven’t seen any actual storm activity with our eyes, meaning a front coming through that kicks up dust and causes a really thick dust cloud to sweep across the landscape,” said MSL Project Scientist Ashwin Vasavada, of JPL.

That’s not all that surprising, given that “the meteorology is so different in that 6-kilometer deep crater there, which kind of has its own system,” Zurek pointed out.

Being more or less spared by the storm and not having to rely on the Sun for energy of course has made a considerable difference. Even so, the roving laboratory did report an opacity of “approximately 8.5” on its Sol 2085” (June 18, 2018), which, “is subject to reanalysis,” said Lemmon. Since that peak however, the opacity over Gale Crater has dropped to “below 4,” he said.

As a result, Curiosity has been able to work through the storm. “We are faring well and plugging along,” said Vasavada. “We really haven’t had to slow down much at all. We’ve just had to take a little extra precaution with the MAHLI [Mars Hand Lens Imager] to avoid the amount of time we expose the lens. And, while we’re not able to cover the cameras on the mast, we haven’t seen any issues with those. They have pretty big baffles around then so the optics are kind of buried inside,” he said.

Curiosity’s engineering cameras are the most exposed. “We have seen a few particles of dust adhere to them, but nothing so far that’s affected our ability to navigate or the ways we use those cameras,” Vasavada reported.

It’s the lighting conditions that are having the most impact on Curiosity’s work. “All this dust in the atmosphere makes the sky darker and also colors the light pretty significantly,” Vasavada said. “Mars always has a little bit of color in the light, but instead of getting the white light we hope for, we get light that is more orange than the usual Mars light. So it’s very difficult for us to use color information to do geology when the dust storm is going on.”

But the Curiosity team is managing the illumination conditions with longer exposure times and scheduling the imaging earlier in the day. “These are all secondary kinds of things and easy to deal with,” said Vasavada.

Lemmon has taken to planning the Curiosity Tau observations, as if the storm is “in a mode of persistent decline,” he said. “It seems like the dust will be with us for months, but we are using a decay-model to plan exposure times, and we have also gone to a post-storm cadence of Sun imaging.”

As for when the MER team might hear something, even a beep 'Hello, I’m awake' from Opportunity “could easily be 5-7 weeks,” Lemmon estimated, or when the atmospheric opacity has dropped to around a Tau of 2.

In a comparison with the 2001 dust storm, scientists corroborate that estimate, predicting that the opacity at Endeavour Crater should drop down to 2 or so sometime in September – “if things track the way they did in that storm,” qualified Zurek.

Nevertheless, the MER ops team is continuing to vigilantly listen every day for the rover during the programmed fault communication windows, as well as through the Deep Space Network (DSN) Radio Science Receiver (RSR), as reported in last month’s MER Update. The team has also been sending a command at least three times a week to elicit a beep if by some unexpected chance the rover happens to be awake. “All is quiet,” summed up RP Paolo Bellutta, who is hoping to chart Opportunity’s next drive sometime before the end of the year.

“If the opacity is lower, there is more sunlight and energy going into the batteries and that starts to accumulate, and eventually the batteries will be charged enough that the vehicle will wake up, assuming it is in good health,” said Callas. “That’s our expectation.”

What the MER team knows for certain is what they still don’t know. “There are many different scenarios and many different possibilities when it comes to what state, what condition Opportunity is in,” said Lever. “I’ve shot back and forth between all the different scenarios, but we’re guessing here. We will not have any answers until we hear from Opportunity and get some actual data,” he reiterated.

The waiting and not knowing hasn’t been easy. “It’s been a difficult time, but we’re trying to stay positive because we have lots of reasons to be positive,” said Stroupe. “We have every reason to think from all of our models that we could well be okay. The storm models indicate that once the lifting centers stop raising dust, this storm should follow a semi-predictable decay and we should be somewhere on that curve now. All our other models indicate that the rover should be okay, that it hasn’t gotten too cold to impact the electronics and science instruments.”

There are however also a number of other factors to take into account. Although Opportunity may be able to see the Sun now, it may take a while for her to recharge enough to rise and shine. Also, there may be dust on the solar arrays that really diminish the rover’s power production.

As always, the MER team will move carefully and cautiously when they reestablish contact with their ‘bot. “We’re in the process of developing a recovery plan,” said Callas. “It’s likely though that we’re not going to take any action until we have heard from the rover for several sols, so we can understand the state it’s in, the mode it’s in and get an idea of its health.”

Remarkably, Opportunity was still operating under master sequence control when she sent her the communiqué the MER team received on June 11th, even though she was only generating 22 watt-hours of energy, which is not enough to even ensure the clock would continue ticking for much longer. [The robot’s power production capability on landing with clean solar arrays was 950+ watt-hours and prior to the storm she was producing upwards of 650 watt-hours at the end of May.]

But soon, if not immediately after sending that downlink, Opportunity shut down and went to sleep. The team has not heard so much as a beep since then. But how exactly she shifted into sleep is not known. While there is a possibility that the rover simply shut down and went into DeepSleep after sending that downlink to Earth, the ops engineers will still have to tend to her when she wakes up.

“There are likely going to be three overlapping fault modes on the vehicle: low power fault, the uploss timer fault, because we’ve gone so long in communicating with the vehicle, and mission clock fault,” said Callas. “Now there is a hierarchy to each of those faults, and we will have to unwrap each one of them as we go.”

Most of the ops team engineers believe that the rover’s extreme, never-before-seen low power level of 22 watt-hours, combined with the record-breaking Tau of 10.8, had to have tripped the low-power fault shortly after Opportunity sent that missive. That fault automatically shuts down all the robot’s systems except for the clock.

The team does know for sure that the uploss timer faulted, because it was set to expire after 28 days and was sent up during the last uplink to the rover on Saturday June 10th, Oppy’s Sol 5110. “So that expired on July 7th,” said Nelson.

The uploss timer is a kind of “watchdog timer,” standard to all operating robotic spacecraft. The MER engineers sets this timer every time they command the rover. If it times out and faults, it’s an indicator to the rover that there may be a problem, and the robot is programmed to go through a series of steps to rectify the situation, including phoning home during a preprogrammed communication window.

The recovery plan, said Nelson, consists of three phases: 1) a listening phase to determine when the rover is trying to communicate with Earth and what mode or fault the rover is in; 2) a recovery phase wherein the team acquires more information about the rover’s state and health, re-sets everything that has faulted, confirms the status of the batteries, turns on the UHF antenna, and whatever else it takes to return the vehicle to a nominal state; and 3) a final check out phase during which the team will characterize how much dust is on the lenses of the camera, taking some Taus, and calibrate the Pancam Mast Assembly and the High Gain Antenna, and generally checks out the rover to make sure that nothing got damaged during the storm.

“Once we have decided, from an engineering standpoint, that the vehicle is in good operational state, we will give the ‘keys’ back to the scientists to continue their operations,” Nelson said.

When Opportunity does take in enough sunlight to recharge and wake up, if the mission clock faulted, that will override everything else and the rover will be in that fault mode, Nelson said. “If we recover out of that, the next priority, the next fault on the list is the uploss fault, but not until we recover the mission clock will the rover’s flight software recognize the uploss fault.” From there, the engineers will address the low-power fault.

Not everyone agrees the clock necessarily faulted. If the Tau dropped from 10.8 the following day, and the rover took in enough sunlight to boost her energy, “it is possible that the rover was able to produce enough energy to keep the clock ticking,” said Lever.

“The clock is a one-watt device, so in 24 hours, it will consume 24 watt-hours and we were generating 22 watt-hours when we last had contact,” said Callas. “It’s tiny. But it’s not zero. So, there is a possibility that maybe that was the worst it ever got and the clock has stayed running,” he said cautiously. “Which would be great because that would make recovery much easier.”

If Opportunity did trip the clock fault, “it’s going to be a bit of a game of whack-a-mole because we won’t know exactly what time the rover will communicate with us each day because of this combination of different timers and energy on the solar arrays,” Callas said. “So we may hear from the rover one day but not on the next day or the day after and then we may hear from it from another time. We need to understand that pattern to figure out what the state of the vehicle is.”

The good news is that there is “probably only a window of a few hours in which the vehicle will wake up each day, roughly between 8:30 to 1:30 Local Solar Time (LST),” said Callas. While that is much better than having to search through an entire 24 hours and 39 minutes every Martian day, “it will complicate things,” he said.

In addition to developing a strategy for recovery, the engineering team will do some testing on the ground with two engineering rover testbeds at JPL, said Callas.

Once Opportunity is able to charge her batteries and phone home, recovery can begin. “Anything above 24 to 40 watt-hours a day, which is sort of what the parasitic loss will be to the electronics, will go into charging the batteries,” Callas said. “So if Tau has dropped over the Opportunity site then sunlight will generate energy and we will begin to charge the batteries.”

This much is certain: recovery will take a while. “Once the rover shuts down, it takes time for it to get back up online and working,” said Stroupe.“We may hear from Opportunity briefly and then that downlink effort may drain the battery enough that she goes back into low power fault. So she may oscillate for a while.”

Until they hear that beep, the MER team is “also doing all the other activities we need to do,” said Callas. “We still have a flight software build we’d like to do when we get the rover back. We’re managing our workforce and trying to minimize the taxi-meter running on the project right now.”

Meanwhile, NASA’s orbiters at Mars are continuing to study various aspects of the PEDE. The two primary instruments on MRO that are tracking this storm are MARCI and the Mars Climate Sounder (MCS), which measures the temperatures in the middle atmosphere.

“When the dust is lifted high into the atmosphere, it heats up the atmosphere at least in the daytime,” said Zurek. During the last week of July, “the temperatures have either not risen further or are actually beginning to drop in some areas. So the atmosphere is beginning to cool down a little bit as the dust is falling out and not as much dust ends up absorbing the incoming solar radiation.”

Since the dust cloud encircling Mars blocks the orbital cameras’ views of most of the Red Planet, those instruments have been focused on the south polar area because the dust is not so extensive there. “As the dust kind of clears out, we will start trying to image other areas again as the surface features reappear,” said Zurek.

“These storms are pretty much the major component of inter-annual variability for the Mars climate, meaning they are the biggest change is from year to year as you go forward.” Said Zurek.

Every one of these PEDEs is different and this one is no exception. “There are two things that stand out about this storm,” said Zurek. One is that this was an early storm, meaning it started just as southern spring sprung in the southern hemisphere of Mars.“We did see one just a tiny bit earlier back in 2001, but we thought that one was very exceptional.”

The other notable factor is that the local dust storm that triggered this PEDE started out like many of the others do. It began in the high northern latitudes and followed the Acidalia storm track, cruising through Chryse and nearby Meridiani Planum and Opportunity, as reported in the last issue of The MER Update. “Normally those storms will go into the southern subtropics before they expand into a regional storm or they just die out,” said Zurek.

This storm, however, has not been “normal” in that sense. “This one was kind of unique in that it sort of parked over those equatorial latitudes, almost over Opportunity so to speak,” Zurek explained. “It just kept churning away for several days raising a lot of dust into the atmosphere, while other centers began to develop off to the east. Then it kind of bloomed from a regional storm into this planet-encircling dust event.”

The fact that this storm took a while longer than other storms to develop into a PEDE, also makes it interesting for the scientists studying these huge tempests, one that may provide them with additional clues about how local storms develop into such big events.

“We hope when we have all the data acquired from the various spacecraft and start comparing details that we’ll be able to tease more out of just what triggers that regional activity and such,” said Zurek. “There have got to be some clues in all this data that will help us understand how these storms evolve.”

Interestingly, the atmosphere is probably going to still be hazy and there will still be noticeable dust in the atmosphere at the time of InSight’s arrival on Mars in November, Zurek said. “That’s assuming of course that we don’t have a second dust storm that picks up about that time, like happened during the Viking years.”

However there are a couple of other things to remember. One is Mars is still moving toward perihelion, so it’s still getting more sunlight every day at any given place on the planet, noted Zurek. “But it’s no good if the dust just falls out of the atmosphere and onto the rover’s solar arrays. We’ll need some cleaning events,” he said. “Actually, the fact that there has been some dust raising activity not too far away – although they do not seem to be raising dust there now – maybe suggests that there are winds at the Opportunity site that may be able to take care of that.”

Since the winds tend to blow up from the bottom of Endeavour, Opportunity, which is parked inside the crater’s western rim halfway down Perseverance Valley, is positioned well to catch any dust gusters that may blow by. Time and Mars will tell.

In the meantime, everyone it seems, from the Mars Program Office to the orbiter teams to the Curiosity team to people around the world, are rooting for Opportunity. “Right now, it’s kind of a race between the dust going away and getting more power on the arrays,” said Zurek. “But we are cautiously optimistic.”

Added Vasavada:“You’ve definitely got 500 scientists on Curiosity who all have their fingers crossed that Opportunity is going to make it through this storm.”

As grateful as the MER team is for that support, every one wants to get back to work on Mars. “People came to work on this project because they want to work on Mars, and right now we’re not working on Mars,” said Callas. “So people are anxious and understandably concerned. But we are hopeful and we’ll do the necessary work that needs to get done to try and recover the vehicle. Still, there is stress, as you would expect. We are human beings.”

Yes, human beings who are exploring Mars and blazing trails on NASA’s first overland expedition of Mars with the help and undaunted determination of a colleague and field geologist that happens to a robot hero.

Despite the darkness of the past couple of months, if history tells anything about this legendary mission, it’s that positive thinking and belief in the team’s collective capability and ingenuity makes all the difference in meeting the challenges of exploring Mars.

“People still have moments I think where it hits them and it’s troubling,” said Stroupe. “Even so I think our optimism is real, though guarded, because Marsishard and no one knows for sure what’s going to happen. But the team is really hanging in there and working hard and putting everything into trying to make sure that when we do get that signal, we are 100% ready to go to help recover the spacecraft.”

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth