A.J.S. Rayl • Sep 04, 2013

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Begins Science at Base of Solander

Sols 3385 - 3414

Mars Exploration Rover

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Maas Digital

There wasn't a dull moment for the Mars Exploration Rover (MER) mission in August as Opportunity drove up to the base of the Solander Point section Endeavour Crater's eroded rim, crossed over a geological boundary between ancient eras, maneuvered through a boulder field, scooting unscathed from a near-miss with a rock that could have ended it all, and at month's end delivered her team to what looks to be another scientific gemstone on the Red Planet.

While NASA, the world, and the global media celebrated the newer, bigger rover, Curiosity on its first year of operations, in the Martian shadows Opportunity was staring at something new once again - more than nine and a half years after bouncing down on Mars, landing inside a small crater, and taking the world by storm.

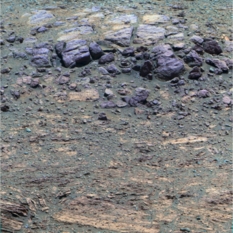

It's a small cliff or escarpment that runs for some 80 meters along on the eastern side of Solander Point, just to the south of the northern tip. "It's really spectacular," said Ray Arvidson, MER deputy principal investigator, of Washington University St. Louis (WUSTL) "It's about 40 centimeters (1.3 feet) high, and has boulders in it and a cap rock on top of it. We've never seen anything like this," he said.

Larry Crumpler, MER science team member of the University of New Mexico, described it as "peculiar."

It might be an eroded part of the ancient terrain that forms the base or bench area of Solander Point, the apron layer that seems to surround each of Endeavour's rim segments. Or it could be something else. Opportunity was slated to work through the long Labor Day weekend to find the answer. "It's too early to tell anything yet," said Arvidson, who is overseeing Opportunity's sixth winter science campaign. "This is true exploration and discovery."

Since arriving at Endeavour Crater in August 2011, Opportunity has returned some of her most significant science discoveries since leaving Eagle Crater back in 2004. For the first seven years, the robot field geologist found plenty of evidence for past water, which it was sent to do. But the water was highly acidic. Endeavour Crater has changed that. The evidence - notably Opportunity's recent ground-truthing of clay minerals on Matijevic Hill at Cape York - has been pointing to an environment with flowing water that was more alkaline or neutral, like the water we know on Earth.

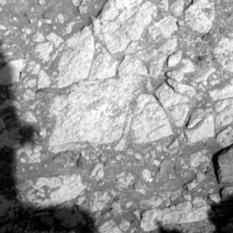

Scarpin' it up

Opportunity took this photograph of the weird escarpment or little cliff it roved upon at the base of Solander Point in August, and which studied up close throughout the Labor Day weekend. It is about 40 centimeters (1.3 feet) high, according to Ray Arvidson, MER deputy principal investigagtor, of Washington Univeristy St. Louis. "It has boulders in it and a cap rock on top of it. We've never seen anything like this," he said.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

After completing a two-and-a-half month, 2.2-kilometer journey from Cape York, Opportunity pulled up to Solander Point during the first days of August. Although the mission declared arrival in July, the rover made actual "landfall" in the Bench or apron area surrounding the Point, along the inboard or eastern side of about 90 meters to the south of the northern tip. On time and with an ample supply of energy, the rover wasted no time checking out the new digs.

Like Cape York, Solander Point is part of the western rim of Endeavour Crater, which is about 14 miles (22 kilometers) in diameter. Where Cape York exposes a few meters of vertical cross-section through geological layering however, Solander Point exposes "about 10 times as much," according to Arvidson. Like rings inside trees, every layer marks a different time and tells a different story.

It almost goes without saying that discoveries are there for the making in this section of crater rim and the postcards Opportunity sent to her crew in August gave the MER scientists their the first chance to take it all in close up. The science team is "kind of like in Disneyland," said John Callas, MER project manager at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), home to all the American Mars rovers. "Some people want to go on Space Mountain. Other people want to do the Haunted Mansion, and others want to do It's a Small World."

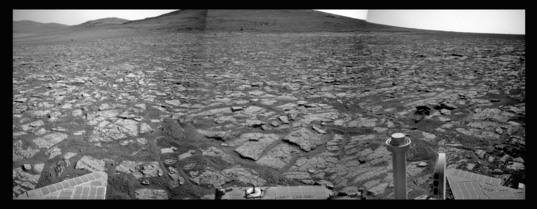

There is much to see at Solander Point. For starters, there is the contact, a kind of boundary line or border between ancient geological periods on Mars. This one appears to separate the Meridiani sandstone plains and sedimentary rock that the rover's been studying and roving across since landing in Eagle Crater up to arriving at Endeavour, and which likely formed in wet and acidic conditions long, long ago, from the more ancient layers and tilted and broken rocks at the base of Solander Point, which were uplifted by the impact that formed Endeavour Crater and which date back to when the area is believed to have featured a more neutral water environment.

Loose rocks and unusual dark boulders that seem to have rolled down Solander Point's slope are scattered around the contact, some on the Bench and some just outside. Looking up slope, a boulder field extends on the flank of the hill, emanating from what appears to be a source nearer to the top. And then there is the weird escarpment, the target of Opportunity's Labor Day research.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

Pulling up to Solander Point

Opportunity snapped the pictures that went into this view of Solander Point in early August with her panoramic camera (Pancam) as she was approaching the base of this part of Endeavour Crater's eroded rim. You can see the escarpment where the robot field geologist spent Labor Day in the distance, at the base of the hill, just left of center. Stuart Atkinson, MER poet and member of UnmannedSpaceFlight.com, processed this photograph from the raw images the rover returned to Earth. For more of Atkinson's work on MER, see his blog: The Road to Endeavour.It's as if the mission has begun again, again. "It's really true. The mission has begun again," said Arvidson. "We keep inventing ourselves ... new places, new rocks. Hooray for lateral mobility."

The robot field geologist visually documented the boundary area and checked out as many attractions as possible August, even venturing up slope into the boulder field to compare rocks and layers there to those the rover found at Cape York. "We have been doing short hops, really looking at the layers in the rocks, and stopping frequently to do IDD and photograph all these boulders, checking out the contact, and collecting a lot of really interesting data," said Ashley Stroupe, one of the rover planners who drives Opportunity.

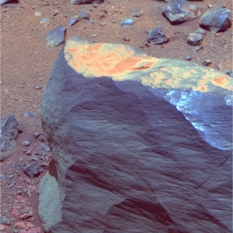

One boulder, Red Poker, turns out to be readily familiar, of the layer most traveled by Opportunity, known as the Burns Formation. Another boulder, Tick Bush, is basaltic, also typical of what the rover has seen around Meridiani Planum. But a flat, light-toned rock dubbed Platypus is older, of the Bench, and part of the Grasberg layer or rock unit the rover first discovered in the rock Grasberg, on the Bench at the northern end of Cape York back in July 2012.

It's a likely preview of what Opportunity will find in the months to come, and there will be a lot more to come, some of it not yet imagined. Fortunately, the rover is roving on to delve into the mystery. With a little less luck, it might not have been.

While navigating the boulder field in mid-August, Opportunity apparently came frighteningly close to running into a boulder called Mulla Mulla. "It was a near miss," said Bill Nelson, chief of the MER engineering team. "We could have easily collided with the rock and damaged the rover. Through sheer luck, we didn't."

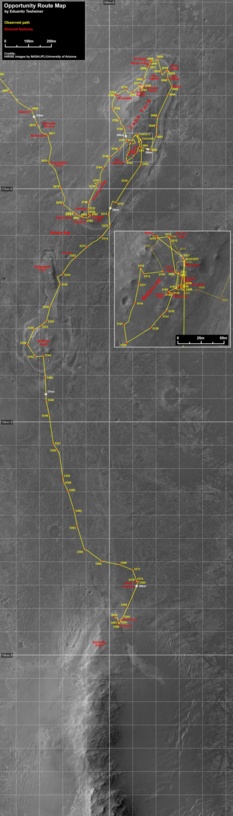

Opportunity's trekking grounds

This image, taken by the HiRISE: High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) is labeled to show Cape York, Opportunity's last neighborhood, and Solander Point, the neighborhood it is now in and exploring. The robot field geologist will be spending its sixth winter on the north-facing slopes of Solander Point's western side.NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA

As it turned out, Opportunity didn't even so much suffer a scrape and moved on without so much as a blink to Platypus. But it might have been mission catastrophic, as they say in the space business, and it happened because of human error. "This is an operational error and it's a big deal," said Callas. As a result, the incident generated what is known as an Incident Surprise Anomaly (ISA) report. "We want to thoroughly understand why our process didn't catch it, because it should have. We want to make sure that we are always on our A game."

From Platypus, Opportunity headed north toward the northern tip of Solander Point, stopping at the escarpment to work through the Labor Day holiday weekend.

Speaking of labor, it takes a lot of work to operate a mission on Mars. Amidst rover ops and other obligations, MER team members continue to do the hard and tedious work behind the scenes to ensure Opportunity has everything it needs, and that all its instruments are being used wherever possible. "We want to maximize the utilization of these assets, because they are so precious and so valuable," said Callas.

In August, for example, the MER engineers at JPL spent time working on tweaks to the parameters on Opportunity's shoulder elevation joint, aka Joint 2. This joint is responsible for the up and down motions of the instrument deployment device (IDD) or robotic arm and in July it began stalling. "We believe we can avoid these stalls by making some adjustments," said Nelson.

The MER engineers are also investigating whether or not they can reactivate Joint 1, the joint that controls azimuth or the horizontal left-to-right, right-to-left motions of the arm. Although it was declared dead and taken out of use years ago, there is some thought that maybe it can safely move small amounts, something that would help the rover more efficiently position her arm over targets. With that joint completely out of commission, the rover often has to move its entire body to position the arm over a chosen target.

The behind the scenes work also includes maintenance and upkeep of the Surface System Test Bed (SSTB) rover at JPL on which all this is tested. A planned power outage to upgrade some equipment in the building where this ground rover is housed took Opportunity's Earth ops sibling out of commission for much of August. "We powered down ahead of that building outage, but when we powered back up, we lost communication and were not able to use our SSTB testbed," said Nelson. In the waning days of the month though, the engineers made sure MER's Earth sibling was repaired and back in service.

The MER project management team is still looking years ahead too. One thing it is currently contemplating is how to adapt data downlinks when Mars Odyssey's orbit changes. The orbit of that spacecraft has been drifting, as spacecraft orbits do, and it will eventually have to undergo a propulsion maneuver to stop the drift. When it does, the Odyssey team wants to shift the spacecraft's orbit so that it passes near the poles and the planet's terminator in early morning, around 7 am, because scientists want to study the clouds, sublimation, and evaporation that occurs in the early morning hours, things that have not been studied since Viking. That means Odyssey would orbit over Opportunity at 7 pm local Mars time, when the rover is in DeepSleep, a mode it must enter each night because of an errant heater that is stuck on and drains power.

Mulla Mulla

Opportunity took this picture of Mulla Mulla on her Sol 3405 (Aug. 22, 2013) with her Pancam, several sols after it almost had an undesired close encounter with it. "It was a near miss," said Bill Nelson, chief of MER engineering. "This is an operational error and it's a big deal," noted John Callas, MER project manager. The incident, which was attributed to "human error," is being investigated so it doesn't happen again. "We want to make sure that we are always on our A game," Callas said.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

"We're working different strategies that include having Opportunity stay awake longer in the summer and relying on MRO in the Martian winter months, even though MRO passes are shorter and less data can be downlinked," said Callas. "We are also working directly with the Odyssey team."

It's for good reason. All indications are that Opportunity's outlook for the future is about as bright as one could hope, and once the robot field geologist makes her way over to the western side of Solander in September the prospects for discovery escalate dramatically.

That's why - even after nearly 10 years of working on this mission - there is newfound excitement building among the MER engineers as well as scientists. "It is catching," said Stroupe. "We realize we're in a totally new place and doing new stuff and making complementary observations now of what Curiosity is going to be doing when they get to Mt. Sharp area, so everybody is really excited."

Rather than dreading the terrifyingly cold season, the MER team is welcoming it and it would appear that Opportunity is on the same page, ready, willing, and still able to carry on her expedition. "The rover is performing really well," said Stroupe. "She has been an amazing trooper."

"The rover is doing wonderfully," agreed Nelson. "We've had no hardware problems with her in the past month, and we have not had a recurrence of the Flash memory anomalies in quite some time, certainly none in the past month. That was a primary thing we were concerned about."

Given that Opportunity is on Mars where dust lingers everywhere all the time, it's about as good as it could get. "It's always a Catch-22 with dust on Mars," said Callas. "Either the dust is in the air blocking the sunlight or it's on the solar arrays blocking the sunlight."

Still Mars presented a calm spring and summer and continues to cooperate as winter begins to sneak in. "In spite of having a lot of dust on the arrays, it's not as bad as we initially projected it would be," said Nelson.

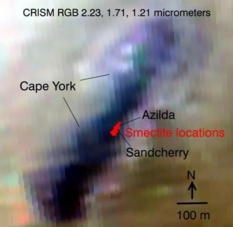

Once Opportunity finishes its investigation of the escarpment, the robot field geologist will make the drives counter-clockwise around the northern tip of the Solander Point and to the western slopes. Based on detections made by the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM), an instrument onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter that searches for past and present signs of water, as well as Opportunity's findings at Cape York, and particularly on Matijevic Hill, it's a given that some of the rocks and layers in these slopes date back to the Noachian Period, when water was apparently relatively abundant in these parts, and the planet, ostensibly, was warmer and more conducive to life.

Finding science 'gold' in the pixels

Ray Arvidson's pixel-by-pixel map of Cape York, shown here, indicates the presence of the signature for clay minerals known as smectite in the red areas. Those areas corresponds to Matijevic Hill and the Whitewater Lake rocks the rover would later examine. This map was created from the initial data acquired by the CRISM instrument onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and additional data that allowed Arvidson to get better pixel resolution. He is currently working on additional data that CRISM took in early August 2013 over Opportunity's next winter haven with which he will produce a similar mineralogical map of Solander Point.NASA / JPL-Caltech / MRO / R. Arvidson

A year ago, Arvidson was able to create a map that pinpointed Matijevic Hill as the "sweet spot" for the clay minerals CRISM originally detected at Cape York in 2008 by meticulously processing additional data, known as along track oversamples, acquired by the orbital spectrometer. That work drove the team and the rover to Matijevic Hill in August 2012. There, Opportunity hit paydirt in a distinctive flat, light-toned rock that the team called Whitewater Lake. Eventually, the scientists concluded Whitewater Lake is an ancient geologic layer, the oldest the rover had ever found - not to mention being where the clay minerals CRISM detected had formed.

Arvidson, who is also co-investigator on CRISM, is currently beginning to process new CRISM data that were taken over Solander Point at his request on August 5th. Like his map of Cape York, this one no doubt will pinpoint where interesting evidence of past water is hiding on the slopes of Opportunity's sixth winter haven. The MER Update will report on what he's found in the next issue.

In the meantime, the scientists for the most part are "itching" for Opportunity to get around the tip of Solander Point, so they can "get back to looking at the true Noachian rocks, the ancient rocks like Whitewater Lake at Cape York," Arvidson said.

As a result of the good weather and aging rover's robust health, projections now indicate that Opportunity should be able to rove and work throughout its sixth Martian winter winter. Solander's western slopes that are gentle and easily navigable and there is a bounty of north-facing perches offering plenty of places where the solar powered rover can position herself and soak up as much of the winter Sun as possible to keep moving and digging in to the scientific "gold" it is bound to find.

"There's a huge area of this hill that meets our tilt requirements for even the worst of winter," Stroupe pointed out. "So Opportunity should be able to do on this north-facing hill what we did with Spirit during her first winter on Husband Hill, explore around making short hops and going from one science target to another." Added Callas: "The only question is, how big of a region will the rover be exploring during that winter time period?"

As remarkable as it is that the MER mission is closing in on its 10th anniversary of surface operations with Opportunity still roving, it is even more remarkable that the robot field geologist returning what some MER scientists are calling "the best science on the whole mission." Perhaps most remarkable however, and most telling of our "higher social order," is that this the veteran rover's month-to-month achievements are mostly done without notice these days, well outside the spotlight Opportunity used to own.

Original Whitewater Lake

Whitewater Lake is the large flat rock in the top half of the image. From left to right it is 0.8 meter (about 30 inches) across. The dark blue nubby rock to the lower left is Kirkwood, which also bears the spherules that Steve Squyres, MER principal investigator, of Cornell, dubbed newberries. Before Opportunity finished at Matijevic Hill in May 2013, the MER scientists concluded that Whitewater Lake is the oldest rock unit that Opportunity has found to date and home to the clay minerals CRISM first detected from orbit in 2008.NASA / JPL / Cornell / Arizona State University

Time marches on. So does exploration, and when the Mars news spotlight shined in August, it wasn't on Opportunity, but on Curiosity, which successfully completed it first year of surface operations.

NASA held a celebration honoring Curiosity's first birthday on the mall at JPL. There were ice cream bars, toy Curiosities that were as "hot" as the weather, and live jazz that kept the tenor of the lunchtime celebration cool.

Saxophonist Chuck Manning struck up a band that featured a familiar "player" to Mars exploration folks, his twin brother Rob on trumpet. Yes, that Rob Manning, chief engineer of the Pathfinder flight system; EDL system manager for MER; and chief engineer MSL/Curiosity. The smooth, inventive jazz stylings the band offered up under the hot California Sun provided a comfortably organic, symbiotic kind of soundtrack for the lunchtime affaire.

Although Opportunity was overlooked by the media in August, she was remembered fondly by the Mars engineers and scientists at the Curiosity celebration. Without MER, long story short, there might not have been a Curiosity. Beyond that, the kudos and lessons learned have a lot to do with the way things have been done on MER, from design to surface operations.

"We learned all sorts of things from MER, said Allen Chen, the Flight Dynamics and operations lead for the Curiosity's EDL team. "We learned about what kind of analyses it would take - literally the simulations we used to confirm that indeed we could land safely are next-generation versions of the ones we used for MER. In fact, a lot of the hardware was inspired by MER, he said, including, believe it or not, the skycrane maneuver that lowered Curiosity to the surface.

"The MER landing system has lots of things connected by soft structures, basically ropes - parachutes connected to backshells connected to landers, all through this big multi-body rope system," explained Chen, who was 'the voice' of Curiosity's historic landing. "That made us less afraid of the skycrane maneuver. That allowed us to consider the skycrane manuever."

"There are so many lessons learned," said John Grotzinger, of Caltech, the project scientist for Curiosity. "Some of it has to do with the science, but most of it is operational," he said. "It's learning to understand with a simple rover - for us Curiosity is complex and MER is simple - how that mission has worked and the way the rover operates tactically. It's the training of the science team, the way to debate strategically, and how to lead a team. MER is a study in how to run a landed mission on Mars. That's incredibly valuable to us."

In fact, Grotzinger, who first went to Mars on MER as a science team member and who became "hooked" after seeing Opportunity's first images still checks in daily. "Even though I'm 150% involved with Curiosity, I still find time every day to look at the pictures from Opportunity, to see what the terrain looks like, to look for some of the things I'm most interested in that might pop up once in a while, and to see how the rover is doing."

And it's not just the scientists who keep coming back to MER. "It's hard to not pay attention to something that continues to churn up stuff so many years later," as Chen put it. "People talk about the fact that we landed in a new place with Curiosity, but Opportunity is seeing a new place all the time. Every time it moves almost, it's in a new place, and that's awesome."

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

The skies over Endeavour Crater remained hazy as August set in at Meridiani Planum, with the team calculating a tau of 0.80. Even so, Opportunity was continuing to produce a respectable amount of power, 395 watt-hours, although her dust factor deteriorated a little to 0.57.

After completing a second set of Pancam images of Solander Point - part of the long baseline stereo imaging campaign that Paolo Bellutta, a MER rover planner, will use to produce a little "movie" of the arrival at Solander - the rover drove into August. She logged 117.4 meters (385 feet) on Sol 3385 (August 1, 20130), then spent a sol recharging, conducting routine tasks, and taking pictures of the view ahead, and on Sol 3387 (August 3, 2013) put another 60.4 meters (198 feet) on her rocker bogie.

With those drives, Opportunity made "landfall" at Solander Point, at what appeared to be a field of rocks and boulders that had fallen down the hill. There were "dark boulders" that had "either weathered out in situ or rolled down hill a little bit," said Arvidson. Some of the boulders were on the base or apron area known as the Bench that surrounds Solander Point and apparently all of the crater's rim segment, and some were just outside the Bench, on the other side of the border.

Opportunity route map

This route map, produced by Eduardo Tesheiner, of UnmannedSpaceFlight.com, traces Opportunity's travels around Cape York through the rover's Sol 3410 (Aug. 27, 2013), and shows the rover's approximate current position. Tesheiner creates his route maps, which are regularly featured in the MER Update, from images taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.NASA / JPL / UA / E. Tesheiner

After a sol of regrouping, for both rover and team members, Opportunity ventured toward one of the rocks outside the Bench area, with a 16.6-meter (54 -oot) drive on Sol 3389 (August 5, 2013). The team called it Red Poker. That same sol, MRO orbited over Solander Point with its CRISM instrument collecting along track oversamples that Ray Arvidson will use to create a more refined mineralogical map to guide Opportunity during the coming Martian winter. But no one seemed to notice. Curiosity was in the spotlight, the Mars story du jour in the headlines. MER pressed on.

With the Sun setting on the Red Planet, Opportunity dutifully finished up her routine chores, then as she has done since the beginning of the mission, she drifted off into DeepSleep mode, far outside the spotlight. Tomorrow was another sol.

Opportunity jumped back into work the next sol. Red Poker in reach, the robot field geologist performed a two-sol touch'n go on Sols 3390 and 3391 (August 6 and August 7, 2013). On the first sol, she focused her Microscopic Imager (MI) and took pictures for a mosaic of a surface target on Red Poker, and then placed her Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS) on the spot for an overnight integration and chemical analysis.

"We identified Red Poker as Burns Formation," Arvidson said later. The next sol, the rover completed the 'go,' driving, 4.7 meters (15 feet) toward another large rock, dubbed Tick Bush.

As the second week of August began on Sol 3392 (August 8, 2013), Opportunity took MI pictures of Tick Bush for a close-up mosaic, and then, as usual, placed the APXS down for a multi-sol integration to glean its chemical make-up and determine its composition. The rover repositioned her APXS with a small offset On Sol 3396 (August 12, 2013), and documented the move by taking a picture with her MI.

That same sol, Opportunity took advantage of the celestial alignment and photographed the transit of both Martian moons, Phobos and Deimos. She photographed a second Phobos transit the next sol, 3397 (August 13, 2013) while continuing the APXS integration on Tick Bush.

As the data streamed down to Earth, the MER scientists quickly confirmed Tick Bush is a basaltic boulder, as they thought. They wanted to have Opportunity quickly check out another like rock - "to make sure the Tick Bush measurements were representative of those basaltic boulders," said Arvidson - but it wasn't to be.

On Sol 3398 (August 15, 2013), Opportunity drove 22.8 meters (75 feet) up slope into the fallen field of boulders. She was on approach to a boulder dubbed Mulla Mulla. The rover drivers were expecting more slip because Opportunity was going up slope, but as it turned out, there wasn't as much slip and the rover got perilously close to Mulla Mulla.

It was defined as a "near-miss" caused by "human error." If the rover had run into Mulla Mulla, it wouldn't have been good, and it could have been really, really bad, perhaps even mission catastrophic. The near miss immediately initiated an Incident Surprise Anomaly (ISA) investigation. "We make mistakes - we are humans - but we have a process that catches those mistakes," said Callas. "This time the process didn't catch the mistake and that's a big deal."

The issue stemmed from a mis-positioning of the 'keep out' zone around the rock. "In hindsight, if you look at it, you go - 'Oh yeah that 'keep out' zone wasn't positioned correctly.' But no one caught that," Callas said.

One explanation could be that the imagery is complex and viewing it from certain angles produces distortions. "But that's always been the case, and yes it made it a little more difficult to try to figure out where to place this 'keep out' zone," said Callas. "But, there should have been multiple eyes looking at that saying - 'Is that right?' That did not occur. We need to understand why and correct that."

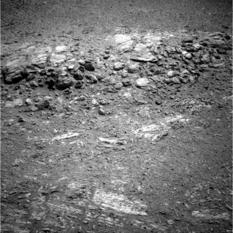

Platypus

Opportunity took this raw image of Platypus with her stereo Panoramic Camera (Pancam) on her Sol 3405 (Aug. 22, 2013). Platypus is the oldest rock the rover examined in August. "It's Bench-like material or Grasberg strata rock," said Ray Arvidson, MER deputy principal investigator, of Washington University St. Louis.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

Opportunity's near-miss didn't cause any change in the rover's schedule, Nelson said, but there is likely to be some impact once the report is finalized and reviewed. "The close approach did not cause us to have the rover do anything differently as far as driving, but it will cause our planning to be different in the future," he said.

Not too surprisingly though, Opportunity was pretty low key the sol after the near-miss. The robot devoted her time to routine measurements and an APXS measurement of atmospheric argon. This observation will go into a dataset the rover has been collecting since the beginning of the mission, basically to determine how much argon is in the atmosphere and the impact it may have on the Martian atmosphere.

As August wore on, Opportunity lost a little energy. With the Martian winter on the horizon, it's expected. Mid-month, the robot field geologist sported levels around 376 watt-hours of solar power. The tau, meanwhile, had decreased to 0.695, and correspondingly, as the dust in the atmosphere rained down, the rover's solar array dust factor deteriorated further to 0.532.

On Sol 3400 (August 17, 2013), Opportunity bumped 0.4 meters (1.3 feet) to position herself over a rock the team called Platypus. She then spent the rest of that weekend, through Monday (August 19, 2013), taking pictures and conducting other remote sensing observations.

The robot field geologist used her Rock Abrasion Tool (RAT) on Sol 3403 (August 20, 2013) to brush the surface of Platypus, and then took the usual MI mosaic pictures and placed her APXS down on the target for a multi-sol integration. As the final week of August began, Opportunity backed away from Platypus in order to get a color picture of the whole rock with her stereo Panoramic Camera (Pancam) on Sol 3405 (August 22, 2013). "Platypus is Bench-like material or Grasberg strata rock," Arvidson said.

Coal Island

This picture shows one of Opportunity's most recent science targets, Coal Island, a contact that is near or part of the escarpment the rover found in August after driving onto the base of Solander Point, a section of Endeavour Crater's eroded rim. The Pancam team processed it and rendered it in false color to make the various constituents easier to see.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

The rover moved on, about 4 meters (13 feet), searching the boulder field for surface targets to investigate, taking pictures of her tracks with her Navigation Camera, and examining the visible geologic contact points along the way. On Sol 3407 (August 24, 2013), Opportunity drove 10.7 meters (35 feet) deeper into the boulder field, taking images and safely dodging some large rocks.

On the following sol, she recharged and took a routine measurement of atmospheric argon with her APXS and the MER science team decided to get on with the journey, and directed Opportunity to head to the north, toward the tip or nose of Solander Point. "Driving on 10 to 13-degree slopes on a boulder field is kind of tough and we were slipping and sliding too much," said Arvidson.

No one seemed to complain. "The scientists have been going nuts with what we're seeing," said Nelson. "This is what they call a target-rich area. And they're like kids with a box full of new toys."

Opportunity drove about 36 meters (118 feet) toward the weird escarpment on Sol 3410 (August 27, 2013), bumping close to a target dubbed Coal Island on Sol 3412 (August 29, 2013) to take a color mosaic with her Pancam.

At month's end, Opportunity was face-to-face with Coal Island and the escarpment in the Bench, still on eastern side of Solander Point south of the northern tip. "We're on the escarpment on the northeastern side, looking at what seems to be a lot of debris coming down the flanks of Solander Point that has been deposited at the base," said Arvidson. "It's like when you're in the mountains and you have all the sediment coming off the hills. This has a lot of big boulders and is now being exposed by wind erosion as an escarpment."

The escarpment is basically like "a huge conglomerate with big boulders, tens of centimeters across stuck in finer-grained material," Arvidson elaborated. "It will be interesting to explore."

Over the Labor Day holiday weekend, Opportunity is scheduled to be scarping it up, so to speak. "It might be a beautiful third dimensional view into the structure Bench, because it looks like a part of the Bench that surrounds Solander Point, Sutherland Point, Nobbys Head, and Cape York," said Arvidson. But, it could be material that has rolled down from Solander Point, or an uplifted part of the Burns Formation. Or it could be something else. "Getting at the answers requires imaging, multi-spectral data, close-up MIs, and APXS," said Arvidson.

The MER scientists and Opportunity are on it. In the first days of September, MER science team members will gather telephonically for what Arvidson calls a "hypothesis fandango." All ideas about the escarpment and other interesting finds, along with proposed studies or experiments needed to address the proposed ideas, will be put on the table for consideration. "As we get into the winter science campaign, I want to make sure we have hypotheses that we are testing, as opposed to just making measurements of cool things we see," said Arvidson.

The labor of Labor Day 2013

More than nine and a half years after bouncing down on Mars and landing inside a small crater, Opportunity spent her August 2013 driving from one rock to another around the base of Solander Point. The robot field geologist ended the month staring at this small cliff or escarpment. It runs for an estimated 80 meters (262.47 feet) at the base of the hill that is Solander Point, along the eastern side and south of the Point's northern tip. The rover was directed to spend the Labor Day weekend laboring on collecting the data that will tell the MER scientists more about this geologic gem.NASA / JPL / Cornell / Arizona State University

Although winter is looming, the future still looks as bright as it possibly could for Opportunity. The tau dropped to 0.646 and so rained more dust down on the rover, which no doubt contributed to her deteriorating solar array dust factor of 0.525. Nevertheless, she is managing to produce power levels upwards of 370 watt-hours at August's end and isn't even on a northern slope yet.

The plan ahead calls for the robot field geologist to continue driving counter-clockwise following the some 80 meters (about 262.47 feet) of exposed escarpment. From there, she'll continue around the northern tip of Solander Point to the western side and into another new scene.

"The interior slope of Solander Point, where we are now, is chock full of big boulders and very dangerous and steep, so we're probably not going to even really try to climb up this side," said Arvidson. The geology on the western side is distinctively different from the geology of the eastern side of Solander Point. The slopes roll gently, offering a number of safe havens for what will be the veteran rover's sixth Martian winter.

There will be, they expect, some breathtaking vistas. "We are looking forward to being able to climb up that hill and get some spectacular views into the crater and back into the plains we came from," said Stroupe. With a nice big area or rolling slopes, most all of which meet MER's winter power needs, Opportunity and her team "should be able to do a thorough investigation of the whole hill, driving across it throughout winter," she added.

"The exposures there are phenomenal," said Arvidson. "There are huge numbers of Noachian outcrops there that we can get to, unlike where we are now."

The current projection, according to both Arvidson and Stroupe, is that Opportunity will probably start the climb onto one of those western slopes in October, depending on power needs. By the time Opportunity gets to that juncture, the science campaign may essentially be determined for them, especially as Arvidson and crew finish up work on the new data from CRISM, which, he reported, "are nicely over the areas where we'll be during winter."

As August fades to history, Opportunity has chalked up another hugely productive month of exploration for the MER mission. "The rover is doing great," said Stroupe. With her health as good as it is and with Mars' continued cooperation, there's no rush this winter. "Once we're on the western side of Solander, we have plenty of time to stop and smell the roses," said Arvidson. "We'll work our way from north to south along the hill, because it's all good."

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth