A.J.S. Rayl • Aug 31, 2008

The Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Exits Victoria Crater, Spirit Picks Up Pace on Panorama

Clear skies and a warming Sun brightened winter in the southern hemisphere of the Red Planet, giving the Mars Exploration Rovers, appropriately enough, an august month. Opportunity packed up, left Cape Verde in the dust, and made headlines when it roved out of Victoria Crater last Thursday. On the other side of the planet, Spirit picked up the pace of photographing its surroundings for its next big, 360-degree, full color panorama, expected to be so lush, so spectacular it's been named for the late, legendary, much honored science artist Chesley Bonestell.

Winter is still a ways from giving up to spring in these equatorial parts of Mars, but it seems safe to say these twin robot field geologists will survive their third Martian winter and establish another record in their exploration of the Red Planet.

Now, four years and eight months into what was originally a 90-day mission and after yet another productive month in the harshest season on a desolate, dangerous planet, "Spirit and Opportunity are doing fine," reported Jake Matijevic, chief of rover engineering at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where the rovers were designed and built.

It took Opportunity just about the entire month of August to complete the series of drives that covered a total of 50 meters (164 feet) and took it back to Duck Bay and out of the big crater it has been studying for years.

For nearly two weeks, the rover struggled to leave the sandy, slippery slope near Cape Verde. "It was a tough drive getting out," said Steve Squyres, of Cornell University, the principal investigator for rover science. "We had gotten ourselves way down deep into the crater and it's treacherous down there."

Once it managed to escape the slope and get back on its own tracks and a rockier road, the rover made swift progress, "basically following the path it took to come over the rim and down the crater wall when it entered about a year ago," reported Matijevic.

Then, late last Thursday, Opportunity roved for 6.8 meters (22 feet) up and over the top of the inner crater slope, through a sand ripple at the lip of Victoria, and back onto the plains, crossing another mission milestone on the way. "The rover is back on flat ground," engineer Paolo Bellutta, one of the rover drivers at JPL, announced early Friday to the mission's international team of scientists and engineers as the confirmation arrived on Earth.

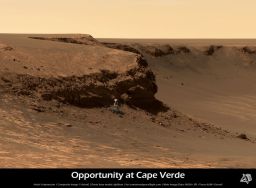

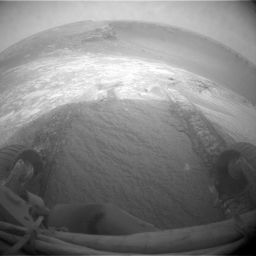

Leaving Victoria

Leaving VictoriaOpportunity roved out of Victoria Crater this month, following tracks it made on descending into the 800-meter-diameter (half-mile-diameter) bowl nearly a year ago. The rover used its navigation camera to capture this view back into the crater just after finishing a 6.8-meter (22-foot) drive that brought it out onto level ground during the rover's Sol 1634 (Aug. 28, 2008). Opportunity laid down the first tracks at this entry and exit point during its Sol 1291 (Sep. 11, 2007), after about a year of exploring around the outside of Victoria Crater for the best access route to the interior. For scale, the distance between the parallel tracks left by the rover's wheels is about 1 meter (39 inches) from the middle of one track to the middle of the other. After getting past the top of the inner slope of the crater, the Sol 1634 drive also got through a sand ripple where the tracks appear deepest.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

The decision for Opportunity to rove on came late in July. The rover had barely completed a campaign this past July of close-up imaging of Cape Verde, one of the promontories that forms Victoria Crater's rim, this 6-meter (almost 20-foot) when engineers saw a spike in current leading to the motor on its left front wheel as it was trying to get to another rock area that extended from one of the cliff's layers, just behind a stately-shaped rock dubbed Nevada.

The target was enticing – and accessible to some of the rover's most sophisticated instruments -- but the event with Opportunity's wheel was ominously similar to what Spirit experienced back in 2006, just before it lost the use of its right front wheel. The MER team decided it was time for Opportunity to bid adieu to Victoria.

"We'd done everything we entered Victoria Crater to do and more," said Bruce Banerdt, MER project scientist, at JPL. "Our main objective going into the crater was to, in effect, repeat the chemical stratigraphy that we did at Endurance Crater and compare the two to see if there are correlations between the profiles of the chemistry as you go down through the layers and back in time through the geology."

For more than half of the 55 months it's been in the Meridiani Planum region of equatorial Mars, Opportunity's focus has been on Victoria Crater. The MER team had selected Victoria as the major destination not long after the rover exited the smaller Endurance Crater in late 2004. While confidence was high, no one was fully convinced it would actually make it all the way to Victoria. The rover's ensuing 22-month journey included stopping for studies along the route and getting stuck in – and escaping from -- a sand trap called Purgatory Dune, an tangle that some worried might be its end.

Opportunity first pulled up to the rim of Victoria in September 2006. Then, for nearly a year, it explored the crater from outside, along the rim, examining from above the rock layers exposed in a series of promontories that scallop the crater rim, and searching for the best, most shallow route in. The rover took its first "toe-dip" into the 800-meter-diameter crater in September 2007. Its objective inside was to go back in Martian time by way of studying the stratigraphy inside, specifically the layers in a tri-color band of rock that encircled the interior of the formation, and the layers in the 6-meter-tall (20-foot-tall) promontory or cliff face called Cape Verde.

Nevada

NevadaOpportunity was on its way to check out this rock target, and the bedrock behind it (from the rover's perspective), which the science team believed extened out from one of the layers in Cape Verde. But an exceedingly dusty and sandy slippery slope and an anomaly with its left front wheel changed those plans and this month, the rover headed out of the crater it's been studying up close for nearly two Earth years.Credit: NAA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / S. Atkinson (color)

Members of the science team had hoped to check out some bedrock that extended out from Cape Verde, near a stately rock called Nevada in July and move in still closer to the cliff face. But the anomaly with the current spike in Opportunity's left front wheel changed all that.

"There's no formula we can turn to that will tell us when it's time to leave," said Squyres. "There's no quantitative rule we can apply and no place we can go and look something up. We have to go by what our gut tells us. Once we had done the super-res imaging of Cape Verde – and we had really gotten most of what we were going to get at this location – we could have continued to make more observations down inside Victoria Crater. But our collective gut began to tell us the continued incremental science value of additional observations in the crater is more than outweighed by the risk of getting stuck in the crater forever."

"The safety of this vehicle comes first," reminded Jim Bell, the lead scientist for the panoramic camera (Pancam), of Cornell University. "We've always operated that way on this project – and we've been able to do great science partly because of that philosophy."

"Certainly if we had any hints there was something fundamentally surprising, new, and different down in the crater that would have changed the tenor of the discussion and made us seriously consider staying longer," said Squyres. "Obviously, we could have stayed in the crater forever. But what we found there was confirmation of the same general trend that we had seen at Endurance. "

Moreover, "there is great science to be had out on the plains," he noted. "It was time to go."

Although the decision was just about made for them, it was still "a tough call," Squyres said. The reason is evident in some of the latest postcards sent home.

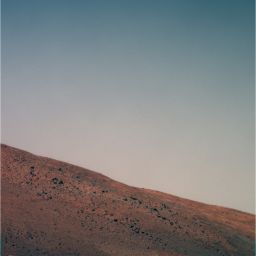

Cape Verde at dusk

Cape Verde at duskOpportunity used its Pancam to shoot the dozens of individual images that have been combined into this mosaic of Cape Verde from inside Victoria Crater. The rover was about 7 meters (23 feet) from the base of the cliff when it took these images on the Sols 1579 and 1580 (July 2 and 3, 2008). Photographing the promontory from this position presented challenges for the rover team. The geometry was such that Cape Verde was between the rover and the Sun, which could cause a range of negative effects, from glinting off Pancam's dusty lenses to shadowing on the cliff face. The team's solution was to take the images for this mosaic just after the sun disappeared behind the crater rim, at about 5:30 p.m. local solar time. The atmosphere was still lit, but no direct sunlight was illuminating the wall of Cape Verde. The result is a high-resolution view of Cape Verde in relatively uniform diffuse sky lighting across the scene. Pancam used a clear filter for taking the images for this mosaic. Capturing images in low-light situations was one of the main motivations for including the clear filter among the camera's assortment of filters available for use. The face of Cape Verde is about 6 meters (20 feet) tall. Victoria Crater, at about 800 meters (one-half mile) wide, is the largest and deepest crater that Opportunity has visited. It sits more than 5 kilometers (almost 4 miles) away from Opportunity's Eagle Crater landing site.

Credit: NASA /JPL-Caltech / Cornell

As Opportunity was heading back to Duck Bay to exit, NASA/JPL released some newly processed images from the mission, including a black and white mosaic of Cape Verde taken at dusk in July. "We had all these problems of having to look into the Sun taking pictures, so we waited for it to set behind the cliff," said Bell. "The sky was still very bright, so it was actually illuminating the face of the cliff, which is entirely in shadow and it turned out to make this spectacular dusk panorama mosaic."

It took a while to process the Cape Verde mosaic, because the data didn't all get downlinked to Earth immediately and, said Bell, "it took until August for us to put it together, because of all scattered light in the images." The processing, actually, is another reason this image is noteworthy – because all of the individual shots that went into this mosaic were taken by the left "eye" of the rover's Pancam. Dust from the global storm in 2007 still shrouds the rover's right Pancam "eye." A color version will be forthcoming, Bell said, but is taking a little longer to process.

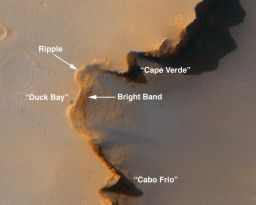

Duck Bay

Duck BayThis image shows Duck Bay, the site where Opportunity rolled down into Victoria Crater and just last Thursday roved out. Duck Bay has gradual slopes of about 15 to 20 degrees and exposed bedrock, which made it the safest place for the rover to enter the crater. This enhanced-color view was taken by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera onboard NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) spacecraft on Oct. 3, 2006.

Credit: NASA / JPL / Univ. of Ariz.

Now driving with its robotic arm or instrument deployment device (IDD) partially open, positioned out front in what the team calls the fisher's position because of an arthritic and unreliable shoulder joint, Opportunity proudly proved this past month that it has the poise and balance of an Olympic gymnast. "The arm has not moved," Matijevic reported. "We take pictures everyday and we do correlations against prior images and there is no movement of the arm."

It's a particularly interesting factoid since Mars has apparently gifted Opportunity, once or twice again in August, with wind gusts that have cleared some dust build-up on its solar arrays. "You can't exactly tell when these things [gusts] take place," noted Matijevic. "All you can tell is from inference that the vehicle is producing a little more energy than it was the day before." In any case, as the month progressed, the rover's power production levels soared from 380 watt-hours to 620 watt-hours. Some of the increase is the result of the changing tilt of its solar arrays as Opportunity moved through the crater, he pointed out, but that cannot account for all of it.

One thing the MER team does know for certain is that Spirit, on the other side of the planet, hasn't been so lucky with the Martian wind. "We wish we had some way to shift power to the other side of the planet," said Squyres.

Despite its dusty solar arrays, which are only taking in some 30 percent of available sunlight for fuel, Spirit saw the temperature rise at Gusev Crater and as it did the demand for survival heating energy decreased. The rover's power production, as a result, improved slightly, from 225-230 watt-hours in July to 233-235 watt-hours in August, enough for it to get back to taking photographs for the Bonestell Panorama, as well as daily monitoring of the atmosphere.

Spirit at Home

Spirit at HomeThis image shows Spirit at its current location on the northern edge of Home Plate in the Columbia Hills,at Gusev Crater. The picture was taken during the southern hemisphere winter solstice at about 2 p.m. local time on the rover's Sol 1591 (June 24, 2008). Home Plate is the elevated round and light toned mesa on the right side of the image. Spirit is visible at the large dark "bump" on the north-northeast edge of the circular volcanic formation. Mid-winter on Mars is the time of the clearest and least dusty atmosphere.

Credit: NASA / JPL / University of Arizona

In fact, the first half of Spirit's winter panorama was among the newly processed images released by NASA last week. The Bonestell Pan's south view, shows in full color this rover's forward view of Home Plate, the circular volcanic formation that it has been studying for many months over the last 3 years or so.

To get one of these 360-degree, panorama pictures the rovers must take hundreds of photographs. Given Spirit's low energy, acquiring the Bonestell Pan has been very slow going and could take much of the rest of the Martian winter season to finish.

"We've gone through this experience before with the McMurdo Panorama," said Bell of Spirit's last winter panorama. "We know we have to be patient." They also know the wait will be worth it.

It was not all that long ago that the engineers at JPL were preparing to put Spirit on "life support" if its power levels dropped too low during the winter, but that dire mode never had to be implemented. The light, so to speak, was always there, it turned out, at the end of the tunnel.

"We're planning twice a week now, filling in the Bonestell Pan, doing atmospheric monitoring, watching the power creep up very slowly, but continuing to creep up," Squyres reported. "Before long we'll be considering some bumps that will allow us to track the Sun with the solar arrays."

Those bumps -- or small movements -- will be made to "shallow out" the solar arrays in order to keep the tilt at an angle for maximum intake of sunlight fuel, Matijevic explained.

The plan right now is to have Spirit move up, not down, at least to see if it can. "We're going to give it a shot," said Squyres. "The bum right front wheel is kind of up on the plateau, so we don't have to force that dead wheel up hill. It's a steep slope, but it's worth a try."

As August comes to a close, the rovers are roving onward into September, with Opportunity taking on new assignments and Spirit working on its winter campaign renewed by the warmth of the Martian Sun.

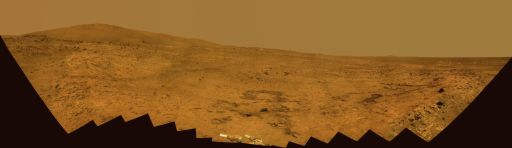

Bonestell Panorama, south view

This 180-degree panorama shows the southward vista from Home Plate North, where Spirit is spending its third Martian winter inside Mars' Gusev Crater. Home Plate, which is about 80 meters (260 ft) in diameter, is an eorded over volcanic formation. This view combines 168 different exposures that Spirit took with its panoramic Camera (Pancam) -- 42 pointings with 4 filters at each pointing. Spirit took the first of the images that are combined into this view on its Sol 1477 (Feb. 28, 2008), two weeks after the rover made its last move to reach the location where it would stop driving for the winter. Solar energy at Gusev Crater is so limited during the Martian southern hemisphere winter that Spirit does not generate enough electricity to drive, nor even enough to take many images per day. The last frame for this mosaic was taken on Sol 1599 (July 2, 2008). Spirit is to finish taking images for the northern half of the scene in coming months.

This is an approximate true-color, red-green-blue composite panorama generated from images taken through the Pancam's 750-nanometer, 530-nanometer and 430-nanometer filters. This "natural color" view is the rover team's best estimate of what the scene would look like if we were there and able to see it with our own eyes.

The northwestern edge of Home Plate is visible in the right foreground. The blockier, more sharply shadowed texture there is layered sandstone whose layering is tilted inward toward the edge of the Home Plate platform. A dark rock on top of Home Plate in that area is a porous volcanic basalt unlike rocks nearby. The northeastern edge of Home Plate is visible in the left foreground. Spirit first climbed onto Home Plate on that region, in early 2006. Rover tracks from driving by Spirit are visible on Home plate in the center and right of the image. These were made during Spirit's second exploration on top of the plateau, which began when Spirit climbed onto the southern edge of Home Plate in September, 2007. In the center foreground, the turret of tools at the end of Spirit's robotic arm appears in duplicate because the arm was repositioned between the days when the images making up that part of the mosaic were taken.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

Spirit From Gusev Crater

The most significant change at Gusev Crater during the month of August was the climate. With a slight decrease in atmospheric dust – known as tau -- and a gradual increase in sunlight and temperature as winter begins to recede, Spirit's power levels slowly edged upward.

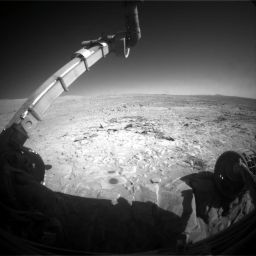

Hunkered down at Home

Hunkered down at HomeSpirit snapped this picture with its front hazard camera on Sol 1506 (Mar. 28, 2008). The rover is in the midst of a winter science campaign and will stay in this position until spring arrives in the southern hemisphere of Mars in late August, early September.Credit: NASA / JPL - Caltech

As it's gotten warmer, the net survival heating for the rover's main batteries and its miniature thermal emission spectrometer (MIini-TES) has decreased, taking some 50 watt-hours, instead of 80 or 90 watt-hours which it was back around the Winter Solstice, according to Matijevic.

"It helps us free up some margin to do more science and so we've been starting to crank out a fair number of frames for the Bonestell Panorama this past month," said Banerdt.

Spirit spent the first two days of August carrying out contingency plans following a delay in data transmission from Earth, implementing a "runout" portion of an earlier master sequence on Sols 1628 and 1629 (August 1-2, 2008). Subsequent relays of new instructions from Earth on Sols 1629 flew without a hitch and the rover got back on its planned schedule.

"The Bonestell Panorama is the main science activity, and we only do a couple of frames of this a week," Matijevic noted. Still, that's more than we had been doing in the last several months."

On Sol 1630 (August 3, 2008), Spirit snapped another column of images for the panorama, then relayed its fresh data via UHF radio frequencies to the Mars Odyssey orbiter to be transmitted to Earth. Basically each column or segment is comprised of "a single pointing of the panoramic camera (Pancam) shot in 13 filters at once," as Bell defines it.

The Art of Chesley Bonestell

The Art of Chesley BonestellThis image shows the dust jacket cover of The Art of Chesley Bonestell by Ron Miller and Frederick C. Durantt III, published by Collins & Brown Ltd, 2001. The late Arthur C. Clarke, who wrote the forward for the book, defined Bonestell's impact as "colossal."

Credit: Collins & Brown Ltd.

The rover filled out the rest of the first week of August recharging its batteries, acquiring six freeze frames for a time-lapse movie in search of Martian clouds with its navigation camera, taking spot images of the sky for calibration purposes with the Pancam, and monitoring dust on the panoramic-camera mast assembly, in addition to receiving new instructions from Earth via its high-gain antenna and transmitting fresh data to Odyssey to be relayed to Earth.

During the last three weeks, Spirit has followed much of the same schedule. "In July, we could typically do one segment a week for the Bonestell Pan and occasionally two," recalled Pancam's Bell, "In August we've typically been doing two segments a week, so we are making progress."

For all that good news, Spirit remains on "a low-activity schedule," said Matijevic, sporting a modest average of 235 watt-hours in August.

As the Martian winter continues to recede, however, plans are being made for Spirit to move, if only a little, in about six weeks. "It looks like from our projection we're likely to do a bump, an actual move in October -- not to start moving out of the area, but to tilt the solar panels less steeply than they are right now," said Banerdt.

"The Sun is slowly making its way south and the angle that we're at, which is roughly 30 degrees pointed toward the north, will be an adverse tilt once we get past about the middle of October," elaborated Matijevic. "That will be the time to try and shallow out the angle."

Spirit could move either up, toward the top of Home Plate, or down the slope from the edge where it has been wintering, Banerdt added. "Originally, when we went over the edge we planned to decrease the tilt of the arrays back to horizontal by going down the slope," said Banerdt. "But recently we've been thinking we might be able to move onto the top of Home Plate."

The fact that Spirit's broken right front wheel is one of the two wheels sitting on the northern edge of Home Plate isn't discouraging anyone on the team at this point.

"We'd rather go up," said Matijevic. "Moving forward would put us back on top of Home Plate when we finally get to a point where we're ready to drive again."

Not only that, but having Spirit rove across Home Plate, instead of down the slope and around it, would save a lot of time and mileage. Actually, it would be a considerable shortcut to getting to this rover's next destinations Goddard and von Braun, which are located to the south of Home Plate. "If we could go straight from the top that could save us several weeks of driving," said Banerdt.

"I think it's possible Spirit can do this," Matijevic continued. "We've made the traverse over Home Plate with the bad wheel. I can't tell you that the terrain will necessarily cooperate. Even though the area we're on is rocky, there's no guarantee we're going to get the purchase with the cleats on the wheels. But it's worth the try, even if we slip. The worst that can happen is we have to back down."

If Spirit does bump in October – which in all likelihood it will – the move, no matter how slight, will impact work on the Bonestell Pan "in a minor way," said Bell, if the rover hasn't completed it by then. "If there were a small bit of motion, it will make it more complex to stitch the pan together, but we can do it," he assured.

Still dusty after all these months

Spirit's deck is so dusty that the rover almost blends into Martian landscape in this image that was assembled from frames taken by the Pancam back on this rover's Sol 1355 through Sol 1358 (Oct. 26-29, 2007). Dust on the solar panels reduces the amount of electrical power the rover can generate from sunlight each sol. While its twin, Opportunity, has experienced the gift of several Martian wind gusts that have clered some of the dust from its arrays, Spirit has not been so luck -- yet.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

Actually, the Pancam team has had to stitch panoramas together before with the mission success panorama way back in January 2004. "That pan was taken from multiple positions as the rover was standing on the deck, so our tools are good enough to stitch together a panorama from images taken from slightly different positions," Bell said. That duly noted, Bell said that his group is hopeful they'll be able to "finish this panorama" before Spirit has to move.

"What the rover engineers say is the right thing to do, we'll do, and we'll deal with the complexity of stitching the panorama together," Bell added, revealing the rare, extreme workability and mutual respect between the scientists and engineers on the MER team. "As we head into September, we may be able to step up the pace even more than we did in August."

For now, the Pancam team is "thinking about the endgame," said Bell, "and how we'll finish up the winter panorama. We want to get all 360 degrees around us, but we're targeting the highest priority areas we can imagine driving once power levels are high enough to drive again a little later this year."

In the meantime, there is the waiting. "All the scientists are eagerly awaiting those extra photons we'll get as the seasons change and the chance to start really doing things again," Banerdt said.

"Of course it's frustrating," admitted Bell. "But at the same time it's good to be alive."

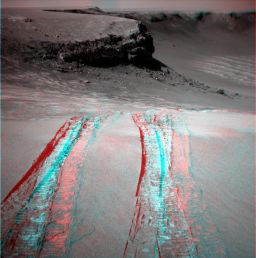

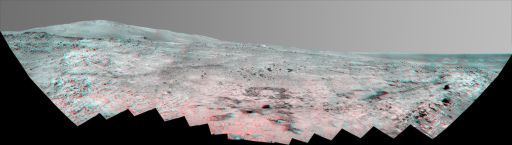

Bonestell 3-D

This southern view of the Bonestell Panorama combines a stereo pair of images so that it appears 3-dimensional when seen through blue-red glasses. On the horizon, the highest point you can see is McCool Hill. This is one of the seven larger hills in the Columbia Hills range. Home Plate is in the inner basin of the range, between McCool Hill to the south and Husband Hill to the north. To the right of McCool Hill, in the center of the image and closer to Home Plate, is a smaller hill capped with a light-toned outcrop. This hill is called Von Braun and it is a possible destination the rover team has discussed for the next season of driving by Spirit, after the solar energy level increases in the Martian spring. The flat horizon in the right-hand portion of the panorama is the basaltic plain onto which Spirit landed on Jan. 4, 2004.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

Back in late July, the plan had been for Opportunity to move in even closer to Cape Verde, the crater promontory or cliff face that it had been imaging from a few meters back that month. The science team wanted the rover to conduct some close-up detection work on a bedrock area behind a stately rock dubbed Nevada that seemed to extend from one of the layers in Cape Verde.

The slope leading to the targeted area, however, was deceiving and much more slippery than it appeared in the pictures sent home and after a spike in electrical current to the rover's left front wheel was detected as it was struggling to get up the slippery slope to Nevada, the MER team decided Opportunity's work in Victoria Crater was done.

"There were a lot of people on the science team who were salivating at the opportunity to get even a few meters closer to Cape Verde and, if nothing else, get even higher resolution imaging of the bedding and maybe even get the robotic arm or instrument deployment device (IDD) down onto this Nevada target – which possibly – if it really is emplace bedrock would have been the lowest stratigraphic position we would have gotten chemical measurements on," noted Banerdt.

"Opportunity's findings inside Victoria Crater showed conclusively that the phenomena we observed in Endurance were actually regional rather than local in scale," elaborated Squyres. "The same thing at two craters 6 kilometers apart – that's one of the big messages. Additional science, which would have taken a lot of time would not have told us a whole lot more about Mars."

The bottom line was that they really couldn't justify keeping Opportunity in Victoria Crater.

Orbital information has indicated that the same general kind of rock covers this whole area, and chances are they weren't going to find anything startling. "Once you've got the story put together -- unless you see something in the data that says – 'Hey there's something really different down here that's worth risking the rover and mission for' – then, it's time to go off in search of something new," Squyres said. Still, it wasn't an easy decision for the geologists and planetary scientists.

"It's mixed emotions," said Bell. "Of course we wanted to get closer in to Cape Verde and do some IDD work on some of the pieces we could identify as having come from specific layers in the cliff. But all of that is tempered by the fact that the vehicle could not move around safely. From the day we decided to go into Victoria Crater, nobody wanted it to be a one-way trip. So when the people who know how to drive these vehicles tell us – 'this is getting to be really dicey, and really risky and if that wheel goes out, we may never come out of this crater,' well -- that's just too much risk to weigh against the potential."

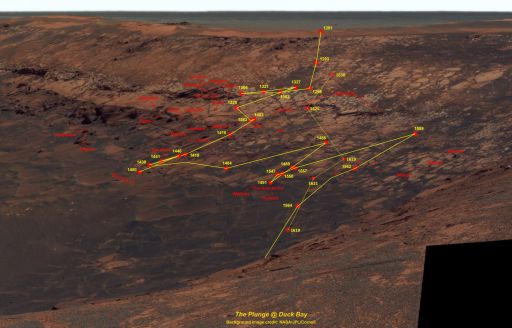

Opportunity's path around Duck Bay as of Sol 1630

Opportunity's path around Duck Bay as of Sol 1630As of sol 1630 (Aug.25, 2008), Opportunity had nearly finished its exit from Victoria Crater. It just three sols, it would rove out of the crater, almost one year after first roving in.

Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell / map by Eduardo Tesheiner with updates by Alan Martin

With the surprise spike in current and Opportunity's constant slipping on the slope as it tried to negotiate its way to Nevada, the decision to leave the crater for good was "more or less made for us," said Bell. "There was really no way to know that this is how the vehicle would interact with that terrain until we got into that terrain – just like at Purgatory. It was a great effort and we got a lot done and we got down pretty far. We got really close and these pictures attest to that. But as a scientist, would we have rather had more – of course!"

Although the anomaly on the left front wheel appears to have been just that – an anomaly, Opportunity's left front wheel was always on the rover team's mind. "If the mission last longs enough, sooner or later we're going to lose a wheel on this vehicle. That's a certainty," said Squyres. "We've got a lot of miles, but remember there are some wheel failure mechanisms that are wear-related, and others that are time and temperature related, how many thermal cycles you go through, and have nothing to do with how far you drive, but how long you've been on the surface. Someday the wheels will fail and we don't know when."

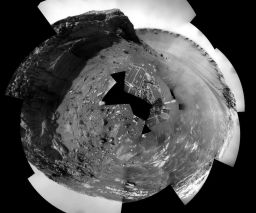

Polar view of Cape Verde base

Polar view of Cape Verde baseOpportunity took a series of images from its Sols 1600 to 1605 (July 25-July 30, 2008) with its navigation cameras and Eduardo Teishner assembled them into this polar version of the 360º panorama. North is to the left. The images was rotated, Teishner noted, for aestetic purposes.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / E. Teishner

Getting out of the big crater even with six fully operational wheels was anything but a cakerove, at least to start with. "It's been a slow process because the first half was on pretty sandy soil on heavy-duty slopes and being cautious about the arm or IDD and keeping our eye on the left front wheel's motor current," said Banerdt.

"There was just a lot of dust and very little of the kind of outcrop rock and the slope was so large this was very difficult terrain to drive through," added Matijevic. "The part of the slope that we were trying to go up was the most traversable of the places in the near vicinity of Nevada, in that it looked like it was comparatively solid and there were a number of emplace rocks in the hillside. However, there was quite a bit of sand or soil that was very loosely composed, so whenever the vehicle made an approach it had at least one wheel in sand and that wheel was tending to dig in and impede the progress up the hill," he explained.

In fact, Opportunity spent the first week of August just trying to position itself for the run back to Duck Bay. "In order to leave the crater, we still had to go over this hill – the hill being up and around Nevada – at least in part, to make our way back to the rocky portions of the crater wall," said Matijevic. "So we spent some time basically going sideways to realign ourselves to go back in the direction from which we had driven to this area. That maneuvering took a few sols, just being able to turn and start moving toward the crater wall."

"We were having a lot of slip and the drives were stopping due to exceeding slip constraints, so we were only getting a few centimeters a day sometimes, less than we had planned," added Banerdt.

Since Opportunity would be going into restricted sols during the last two weeks of August – a period where, because of limited communications with the orbiters above, the rover can only drive every other day – the MER team decided to institute a work regime they call "slide sols" during the second full week of August, a schedule it's used in the past to create more drive sols in a given period of time. "It's a way of using some sols that normally would have been restricted, not quite going onto Mars time, but allowing the planning session to move later in the day," said Banerdt.

"The term 'slide sols' is a euphemism for these transition days between nominal [normal] planning days and restricted planning sols," Matijevic elaborated. "If we were actually on Mars time or following the downlink, we would see each planning day – which routinely takes 6 to 8 hours -- start about 40 minutes later every day. Now because we have reduced staff and changed the process over the last 4 years, we generally plan during the workday here at JPL."

Keeping to an Earth-day schedule means there are sols where the downlink of data comes too late in the day and the uplink with new instructions is too early in the workday so that the MER team can't get a plan together within the workday JPL. Enter the slide sol.

The rover team could just work longer hours or later hours -- and there has never been a problem finding volunteers on this team -- however, evaluations conducted during the last 4 years have shown that longer planning days can make engineers vulnerable to introducing errors in the process. Usually, when people get tired, they make errors, and usually when they make errors, Matijevic noted, it's at the end of the day and the end of the planning process. "That's when we're summing up the evaluation criteria that allow us to be able to certify the plan is safe and ready to go to the spacecraft."

Mistakes don't happen on the MER mission often, but to err is human, after all. "To try and avoid human errors, we try to keep the plans simple and focused enough, so we can get them done within this 8-hour period," he said. That means to keep both rover and team working to their best potential and to not lose precious drive sols, "we slip," Matijevic said.

"Essentially we create a 2-sol plan in which the second sol is a comparatively simpler plan, mostly it's focused on remote sensing, or science that doesn't change the basic state of the components on the vehicle. Slide sols, therefore, the sort of transition period of what would be a normal planning day -- in which we start at 8 or 9 am and finish by 5 or 6 in the evening to a period where we might start as late as noontime and be finished by 7 at night -- to one where we start later in the afternoon working through until late night," he explained. "This kind of schedule requires an agreement by everyone concerned that they're going to shift from a day shift to an afternoon or evening shift, but by going on a slide sol, we create more instances of consecutive days in which we can drive the rover."

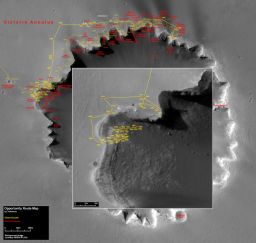

Opportunity's routes

Opportunity's routesEduardo Teishner has detailed Opportunity's routes up to the rover's Sol 1584 (July 8, 2008) over this image of Victoria Crater, taken by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

Credit: NASA / JPL / UA / E. Teishner

During the second week of the month, the Opportunity team started planning as late as 2 pm or 3 pm, then worked to 9 or 10 at night, so the rover could drive every day for a couple more days before the restricted sol period set in. Every sol almost was a struggle, with the rover making only a few centimeters of progress.

"It took until Sol 1621 (August 15, 2008) until Opportunity was actually in a position where it had, for the most part, our wheels on rock," said Matijevic. Then, we started to make some real progress and actually it was basically smooth sailing from then on – a matter of retracing tracks we had made before."

Throughout the series of drives that took Opportunity 50 meters (164 feet) back to Duck Bay, the current spike on the left front wheel actuator or motor never recurred. Some members of the team suspected that maybe the rover had slipped on all 5 other wheels but that left front wheel held its ground causing the spike in current from the force on the motor to keep the rover in place. But Matijevic said they've dismissed that theory. "It was clear after we took pictures of the location the vehicle had been in when this current spike took place that there is no terrain feature that could have explained what wheel(s) would have caught as the others were driving to create a condition in which the current spike would have been terrain induced – so that isn't it," he said.

Analysis has also shown that it was also not caused by an electrical short, nor dust or debris infiltrating the gearbox. And, there was no visible rock sizeable enough to have interfered with the external portions of the gear trains "Those are all possibilities for having occurred to cause something like this and none of them -- seem to be present in this situation," Matijevic said. "These are sealed gearboxes, so it's not like dust or debris from the terrain would have worked its way into the gear train. That leaves only the notion that there conceivably may have been some debris in the gearbox that came loose for a short time, interfered with the turning of the gears, and has subsequently been ejected from the gear train . . . debris from, maybe, parts of the gear tooth. There may have been something residual in the manufacture of the gearbox. It's hard to know what it could have been.

The good news is that whatever the cause, it seems to be gone, at least for now and last Thursday night, on its Sol 1634 (August 28, 2008), Opportunity took its last drive inside the big crater. On its final, 6.8-meter (164-foot) run, the rover cruised up the slope at Duck Bay, over the lip and out of Victoria Crater.

With wind gusts apparently clearing dust from its solar panels on two sols in August, on or about Sol 1620 (August 14, 2008) and Sol 1633 (August 27, 2008), Opportunity left the once 'impossible dream' location – which was more than 5 kilometers (nearly 4 miles) away from its Eagle Crater landing site -- empowered, sporting power levels around 620 watt-hours, up from an average of about 370 during the first part of the month. "It looks as though there might have also been some local improvement in the atmosphere at Meridiani Planum and the rover also picked up some energy by changing the southerly tilt of its solar arrays once it left Cape Verde," Matijevic noted, "but not all of the rise could be accounted for by the tilt or atmosphere or Sun blockage." Plus, he added, "this kind of repeats part of the experience we had in Endurance, where there were just periods where winds came by and resulted in dust clearing, period that don't seem to correlate very well with any physical change in the surrounding terrain or anything like that."

Now that Opportunity is back on the Meridiani plains and raring to go, the science team is instructing the rover to take the time to stop and shoot its tracks before heading off on a science campaign of investigating cobbles. "There's actually some really interesting stuff here," said Squyres. "There are some year-old and 2-year-old tracks at this spot that have been exposed the Martian environment, blowing sand and dust and so forth. We know what the tracks look like when we made them, but what do they look like now?"

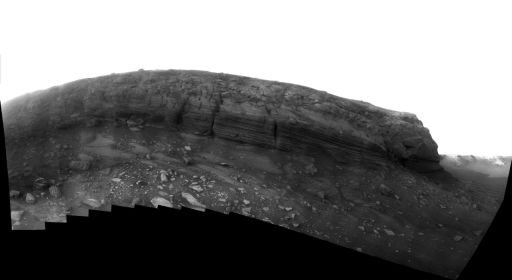

Opportunity's first dip into Victoria Crater

Opportunity's first dip into Victoria CraterOn its Sol 1291, Opportunity finally rolled into Victoria crater. The rover team commanded Opportunity to drive just far enough into the crater to get all six wheels onto the inner slope, and then to back out again and assess how much the wheels slipped on the slope. This wide-angle view taken by Opportunity's front hazard-identification camera at the end of the day's driving shows the wheel tracks created by the short dip into the crater. In the background on the left are Duck Bay and Cape Verde.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

Opportunity first arrived at the rim of Victoria Crater at a place the team dubbed Duck Bay back on Sol 951 (September 26, 2006), then, after circumnavigating about one-third of the crater along the rim toward the north, it returned to Duck Bay to take its first "toe-dip" into the crater on Sol 1291 (September 11, 2007). "The tracks there record sort of a nice two-step history of what's been going on in the way of wind transport in this locale, to understand how things are changing, so we're very interested in imaging those in exquisite detail before we move on," Squyres informed.

If they decide to use the microscopic imager (MI) on some of those tracks, it would give Opportunity a chance to stretch its arm or IDD, which it has had in its traveling unstowed position since May.

Just before its super resolution photography assignment at Cape Verde began -- and because of the unreliable shoulder joint that froze in mid-April during a routine unstow -- Opportunity was instructed to drive with its arm partially unstowed, in what the team calls the 'fisher's position,' because it almost looks like this rover's gone fishin'. By June, after about a month in solitary position, the rover was driving again with its arm partially outstretch to the front. It might seem precarious for a roving robot, dangerous even given the sensitive instruments ensconced in the arm. But the MERs were designed for the rugged Martian landscapes and have spent more than 4.7 years demonstrating their resilience and adaptability.

Even given all that, it still seems remarkable that Opportunity was able to make the journey off the slippery crater slope and all the way back to Duck Bay without so much as moving its arm. "We look at the arm everyday – with telemetry from the potentiometers that are on the individual joints, with images, and other data, and nothing has changed. The arm has not moved," Matijevic said. That's possible, he said, because of the design of the MERs and the implementation of the drives.

"As part of the evaluation on this arm after the shoulder joint froze on Earth, we went back to the manufacturer and asked them to collect the data they had about what sort of forces the individual components of the arm could accept before those forces would cause an actuator to back drive and none of the forces introduced as a result of this driving with the vehicle and the arm unstowed were sufficient at the arm to cause any of the joints actuators to back drive," Matijevic offered. "This was on Earth and in Earth gravity. On Mars, the gravity is one-third that of Earth's, so the likely opposed forces are likely to also be reduced by a factor of three from what we had seen in our sandbox at JPL. Anyway, it was that whole sequence of analyses that led us to have confidence in being able to drive with the arm unstowed. That's been proven now in more than two months of driving."

Rock solid for roving and brimming with energy, Opportunity will soon begin the much-anticipated study of an assortment of cobbles on the plains, perhaps on a field of the intruder stones just to the north, though that is not yet set in Martian stone. "We haven't picked the first cobble yet," Squyres said, "but that's something we'll be thinking about in the next few days."

Whatever cobble is chosen, this research has been a long time coming. "The scientists have been dying to stop and look at these cobbles for quite a while now, but we've had other strategic goals that have always taken precedence since we left Endurance," said Banerdt. "Now, the scientific case has built up for it."

Throughout its travels around Meridiani, Opportunity has found the rocks are pretty similar, "just really minor variations on this sulfate-sandstone composition and texture and some of those variations are interesting and valuable, and we're sort of polishing up the story of the Meridiani bedrock," Banerdt said. "But there's a lot else we'd like to know about Mars."

Dark cobbles at Meridiani Planum

Dark cobbles at Meridiani PlanumTaken on Opportunity took this image of cobbles on the Meridiani Plains on its Sol 660 (Dec.1, 2005). This view was processed from six individual images captured across the visible part of the electromagnetic spectrum to represent what the human eye might see on Mars.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / D. Savransky and J. Bell (Cornell)

The cobbles provide another chapter, another Martian mystery to solve. These small rocks – baseball-size and larger – have come from someplace else, maybe thrown there from impacts that dug craters too distant for this rover to reach or from deep, deep, into the Martian past. "That opens up a whole new vista of investigation, riskier scientifically in that you don't know where these things came from, so it's more difficult to decipher, but it could be a fascinating story," Banerdt pointed out.

As a well-equipped robot field geologist, Opportunity is ready for the challenge and the team is certainly up for a September to remember. "We can use these instruments – the alpha-particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS), the MI, Mössbauer spectrometer, as well as possibly the Mini-TES, if we can get it in shape again -- to pull clues out of these rocks, about their mineral and chemical make-up, their texture, and even possibly where they came from. We have a lot of ways to get to the stories in those rocks and if we do find them, they could open a whole new window into our knowledge of Martian history."

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth