Emily Lakdawalla • Jul 14, 2016

Pluto is not the end

This article was originally published in the April 2016 issue of Sky & Telescope. I thought it was fitting to post it here on the one-year anniversary of New Horizons' historic encounter with Pluto.

When New Horizons flew past Pluto last summer, NASA Administrator Charles Bolden heralded it as "the capstone event to 50 years of planetary exploration" adding that the Pluto encounter "completed the initial survey of the solar system." NASA's science chief John Grunsfeld said: "there is very little terra incognita in our solar system today." These statements are based on an outdated view of our solar system -- the hierarchical view of nine planets, with Pluto at the outer end, accompanied by a smattering of less-important bodies -- and they threaten the future of NASA's solar system exploration.

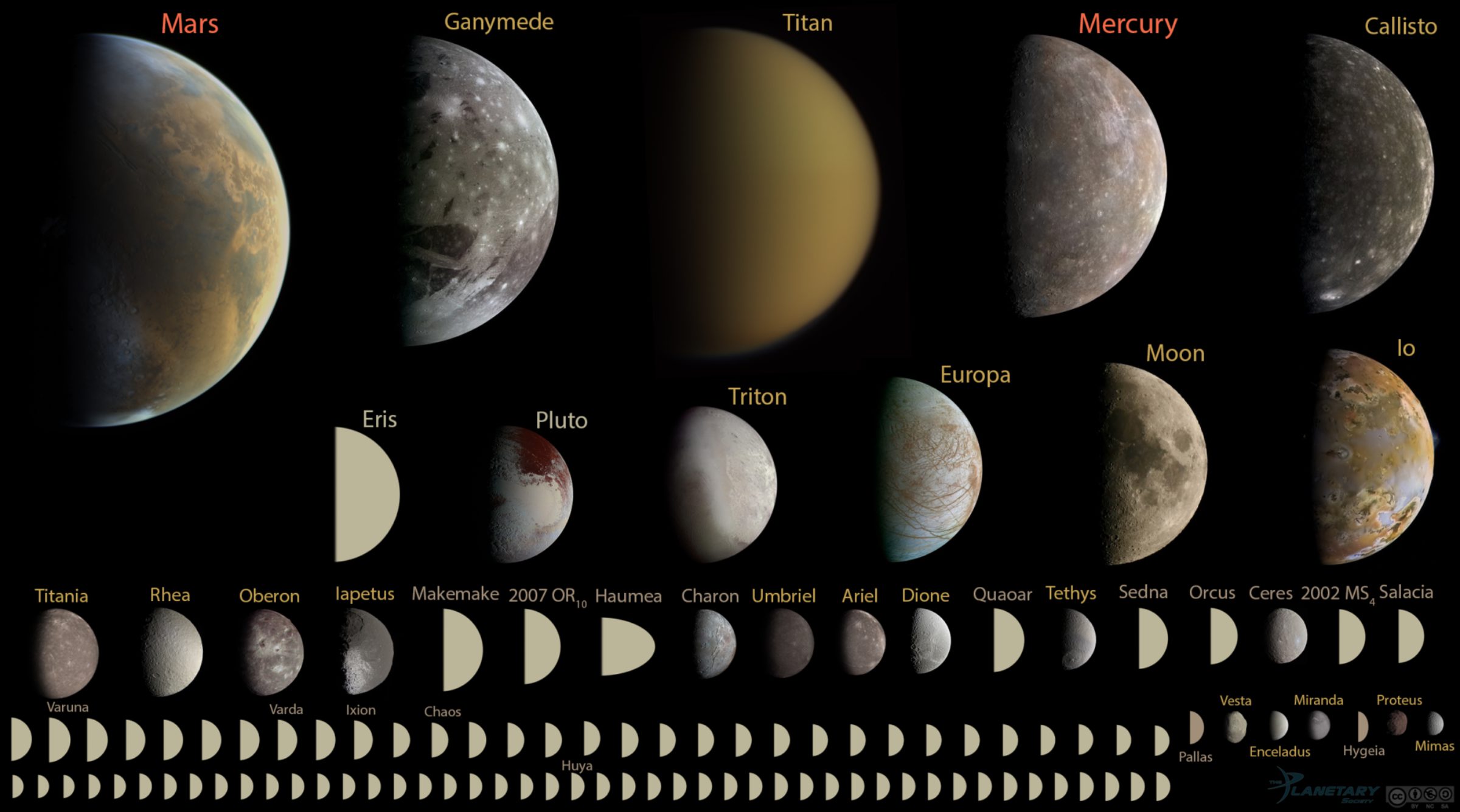

How outdated? For starters, the Voyager encounters with the outer planets revealed the diversity and activity of their moons, many of them larger and more recently active than some planets. Among them are worlds like Europa, Enceladus, Titan, and Triton, each of them as worthy of a dedicated mission as any of the planets.

Then, of course, the discovery of large Kuiper belt bodies unseated Pluto from planethood. We now know about thousands of solar-system objects beyond Neptune. Hundreds of them are large enough to be round, and their varying colors and albedos suggest that they're at least as diverse as the worlds that orbit the giant planets.

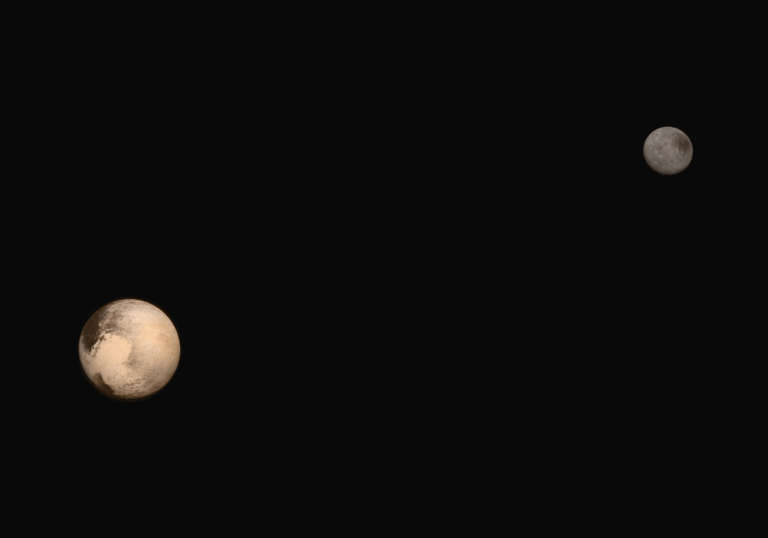

In fact, this "third zone" of the solar system is almost certainly stranger than anything we've seen before. New Horizons' flyby of Pluto and Charon bodies more varied than anyone had imagined. How weird do the other Kuiper belt objects look? Pluto is not the end of the solar system; it's just the beginning of the rest of the solar system. The Kuiper belt -- contrary to what Grunsfeld said -- remains almost entirely terra incognita.

Even within Neptune's orbit exist worlds we've barely touched. We now understand Uranus and Neptune to be a distinct class of planets from Jupiter and Saturn, and they have changed in the quarter-century since we visited them. We need to orbit our ice giants, probe them, and understand what they can tell us about similar-sized exoplanets.

As for those enticing moons, Voyager 2 managed only very distant, low-resolution views of Uranus' moons; Charon's surprisingly youthful surface makes me wonder how most of them truly look. And we don't know how time changes the appearances of these active, planet-circling worlds -- Triton, Titan, Enceladus, Io, possibly Europa.

We have never visited any of the icy Trojans and Centaurs, populations roughly as numerous as the main-belt asteroids. Finally, missions like Rosetta and Hayabusa have shown us the dynamic nature of the solar system's tiniest worlds, and we'll likely never finish our reconnaissance of all of those.

Each time we step a little further into space, we see farther, ask new questions, have new destinations to travel to. But it's a constant struggle to win support for federal funding for robotic exploration beyond Earth. So to have our space-science leaders imply that our work to explore the solar system is in any sense complete is hazardous. We're not done with the solar system. There's so much more to explore.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth