A.J.S. Rayl • Aug 03, 2012

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Works on a Whim, Team to Stand Down for Curiosity

After quietly working through her 3000th day on the Red Planet, Opportunity roved on to new targets near the rim of Endeavour Crater in July, and is now hunkered down at one them, working and waiting, as the Mars Exploration Rover (MER) team prepared to stand down for Curiosity, the new, bigger, more complex Mars Science Laboratory rover, which heads into the seven minutes of terror and landing around 10:25 pm, on August 5 Pacific Daylight Time.

Mars Exploration Rover

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Maas Digital

"Back on the road again is what July was all about," summed up Ray Arvidson, deputy principal investigator of Washington University St. Louis. "It's good to be moving again, good to be collecting data in different places and doing lots of science these days," added Steve Squyres, MER principal investigator, of Cornell University.

But for the next 10 days, Opportunity won't be going anywhere. "Right now, it's all about Curiosity," acknowledged John Callas, MER project manager, of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the birthplace and mission control for all the Mars rovers. "We feel a little like the older sibling with the expectant baby due to arrive any day now, and Opportunity's not getting the attention she's used to," he noted, smiling.

For eight and a half Earth years and counting, Opportunity has demonstrated the now legendary MER mettle, roving across the Meridiani plains, setting and then breaking drive records, surviving dangerous sand dunes, driving into a crater and back out, and finding evidence that, yes, water did once flow on Mars. Through it all, this rover that likes to rove evolved a persona as her human colleagues saw it. This rover was "The Glamour Girl," a "Little Miss Perfect" who loves attention and reveling in the spotlight, compared with her more cantankerous twin Spirit.

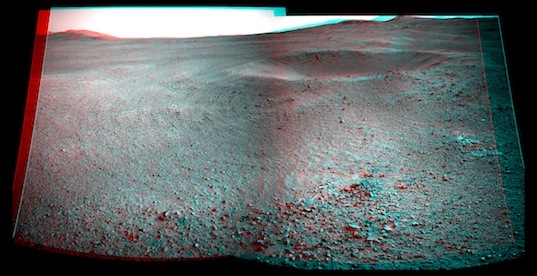

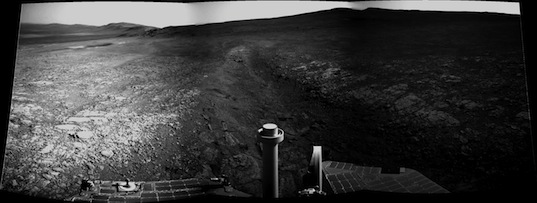

Whim Creek

Opportunity took the images that went into making this stunning view with her panoramic camera this month, while she was on approach to Whim Creek, which is visible in the center of the image. Stuart Atkinson processed it here in black and white. For more of Atkinson's imagery and words, go to his Road to Endeavour blog.NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell/ASU/S. Atkinson

Now Spirit is silent, and Opportunity is a veteran robot field geologist – downright ancient in Mars robot years – and "an emotionally mature rover," Callas added, "that understands these things happen and that attention will be focused on MSL."

Opportunity's longevity has remarkably defied all odds. Even after this rover scored the solar system's first 300-million-mile, interplanetary hole-in-one, landing inside Eagle Crater back in January 2004, no one on the team ever expected that one of their twin robot field geologists would still be roving along when the laser-toting Curiosity came knocking on Mars . . . but soon there will be a new kid on the block commanding the attention and the spotlight Opportunity has grown to love.

The MER team will stand down for Curiosity's entry, descent and landing (EDL) for one week, Callas informed. "We will stand down for what are effectively seven sols beginning Thursday, August 2nd, from -3 days to +4 days after Curiosity lands," elaborated Bill Nelson, chief of the MER engineering team. That means the team will stop daily tactical planning and commanding of their charge.

Opportunity, however, won't get much of a break. "Opportunity will be active the entire time," said Callas, although she won't be roving.

The team began uploading commands yesterday instructing their charge to shift 'gears' into a kind of 'science light' mode, so that the MER mission can give its scheduled time for direct planetary communications with the Deep Space Network (DSN) to Curiosity. "Opportunity will be running out preprogrammed sequences," confirmed Nelson.

Up until now though, Opportunity had been cruising through the Martian spring and revving up for the coming summer. When July dawned at Meridiani Planum, the rover was inspecting a rock called Grasberg, as part of a study of the ancient terrain in northern section of the Bench, the apron that borders the outboard side of Cape York at Endeavour's rim.

By July 10th, Opportunity was back on the road, roving toward one of a trio of small craters for a drive-by photo shoot. From there, the robot field geologist then headed back and slightly west toward a fracture or cut the team calls Whim Creek, located on the northern tip of the Bench bordering Cape York.

There's no water in Whim Creek, and likely never was. "But it's probably our best place in the whole mission to look at the stratigraphy or layering relationships between the Bench materials, like Grasberg, and the surrounding Burns Formation, which is the typical Meridiani sedimentary rock the rover's been looking at since landing in Eagle Crater and up to arriving at Endeavour last year," said Arvidson.

Opportunity is currently parked in the middle of Whim Creek, taking pictures with its stereo panoramic camera (Pancam) of every angle of this trough, focusing especially along the sides, and analyzing a chosen target there with her alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) to try and determine composition of that rock layer.

A thorough examination of the trough will be the rover's science campaign through the stand-down. "We're looking into Whim Creek at the layers, to see if it cuts through the Bench materials and exposes Burns Formation underneath or to see if the Burns Formation is above the Bench," said Arvidson.

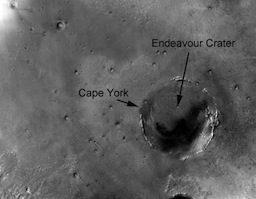

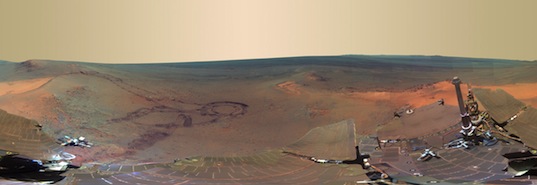

Cape York

This image of Cape York was taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. In the upper right hand corner you can see Whim Creek, the cut or trough that is "probably the surface expression of a fracture in the shallow crust," according to Ray Arvidson, the deputy principal investigator for MER.NASA/JPL-Caltech/Arizona State University

"We've got the APXS down. We figure having it down is better than having it up right?" Squyres posited. "We'll get data where we are, but this is a stratigraphic problem, so we're trying to look carefully at the layering and the focus here is really going to be on imaging." The data the rover collects during the stand-down will be downlinked once a day via UHF and the Mars Odyssey orbiter.

By studying this relationship between the ancient Noachian Period terrain at Endeavour Crater, estimated to be 3.7 to 4.1 billion years old, and the dominant, sedimentary rock layer the rover has studied for the first 7.5 years of its mission, the MER scientists are working to write the geologic story of the area. What environments once existed there? If those environments featured water, what kind of water? And, the big question of course, were they ever potentially hospitable to life, if only microbial life?

In December last year, Opportunity and crew found evidence of hydrated calcium sulfate or gypsum, in a vein deposited by liquid water billions of years ago – what Squyres deemed "the single most powerful piece of evidence for liquid water on Mars discovered by Opportunity."

The scientists know there is more to be found at Endeavour – not the least of which are phyllosilicates or clay minerals, smectite specifically, detected by the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) instrument onboard the Mars Reconniassance Orbiter (MRO) not too far south from where Opportunity is presently parked. But for now, the rover is dutifully carrying out the science campaign at Whim Creek.

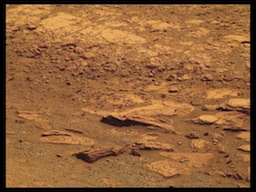

Homestake

Opportunity took this picture of Homestake, the striking vein running through bedrock in December 2011, and Stuart Atkinson processed it here in rich Mars-like color. "This is different than anything we've ever seen with either rover," MER PI Steve Squyres told the MER Update before discovering that Homestake is harboring gypsum. It is one of the most significant discoveries Opportunity has made to date, because gypsum is an indication of an alkaline water, unlike the highly acidic past water that both Spirit and Opportunity had previous found plenty of evidence for.NASA /JPL-Caltech/Cornell/S. Atkinson

The winds of the Martian spring whipped up a couple of storms that briefly darkened the skies over Endeavour Crater in July. "This is the dusty season, so we expect some local storms and maybe some major storms," said Arvidson. "It's what happens on Mars in the spring."

One storm came as close as 360 meters (0.22 of a mile) of Opportunity mid-month, but neither it, nor the one that followed 12 days later, hit the rover's immediate site and both dissipated quickly. As this rover's luck would have it, a couple of tiny gusters in the whirl of winds whisked another fine layer or two of accumulated dust from its solar arrays. But at the same time, the haze overhead thickened and the rover's power levels dropped.

The winds of Mars, as notorious as they are fickle, are a double-edged alien sword. While they are a primary reason the MER mission has survived so long and prospered, one planet-circling event in the Martian summer of 2007 nearly took Opportunity out. So the season rains its own concerns among MER team members.

This time Mars was forgiving. "These storms were not out of family with stuff we've seen before this time of year," said Squyres. And neither the haze nor lower power levels were "enough to increase the fear factor," added Arvidson.

Now at month's end, the dust over Endeavour is clearing and "power-wise, Opportunity's doing okay," Callas reported. The rover is producing more than half its full power potential.

Once Curiosity is on the ground and checked out, Opportunity will finish up at Whim Creek and rove on. "We'll keep working our way clockwise around the tip of Cape York and then start heading south," informed Squyres.

"We'll head south along the inboard side of Bench, which is like a super highway," Arvidson expounded. They'll be on the hunt for "an extensive outcrop" along the inboard side of Cape York that may be harboring those clay minerals seen from on orbit.

While Curiosity is actually charged with groundtruthing the presences of phyllosilicates and Opportunity was not, loyalty looms and a lot of MER team members and followers around the world are silently wishing and hoping that Opportunity delivers the evidence first. It would be another significant scientific achievement for the MER mission – and it would be another moment in the spotlight for the Glamour Girl.

Ground-truthing the clay minerals is meaningful because, as reported here many times before, they are evidence of a kind of alkaline water, water more conducive to the formation of life, water more as we Earthlings know it. Opportunity is ready to rove and it would appear ready to rise to the clay mineral challenge. "The rover is in very good shape and we'll be ready to drive as soon as that stand-down is over," said Nelson. "We're anxious to be back on the road."

How anxious? "It feels like how a car feels when you're revving its engine, but you've got your foot on the brake. It's waiting to break free and drive again, but it can't – and it wants to go so bad," offered Nelson. "We want to be driving. We really do."

But for the next week and a half, the brakes are on and Opportunity will work quietly, in the shadows as Curiosity takes the spotlight.

"If the reason we've got to stand down is because another wonderful vehicle is about to land on Mars, I'm okay with that," chuckled Squyres. "We're just wishing the best for MSL. This is a fantastic mission. It's their time. It's going to be a very exciting night when we land and years of excitement after that."

"Everybody's okay with this," agreed Arvidson. "We're in this business of Mars exploration for the long haul. It's a program not just a mission."

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell/ASU

Greeley Panorama

This full-circle scene combines 817 images that Opportunity took with her Pancam. It shows the terrain that surrounded the rover while it was stationary for four months of work during its most recent Martian winter. The rover took the component images between its Sol 2811 (Dec. 21, 2011) and Sol 2947 (May 8, 2012), while it was parked on a northward sloped outcrop, called Greeley Haven. There, the rover angled its solar panels toward the Sun low in the northern sky during southern hemisphere winter. The name of the outcrop and this panorama are the MER team's tribute to Ronald Greeley (1939-2011), who was a member of the MER team and who taught generations of planetary scientists at Arizona State University. The site is near the northern tip of the Cape York segment of the western rim of Endeavour Crater. On the far left at the horizon is Rich Morris Hill, named in memory of John R. "Rich" Morris (1973-2011), an aerospace engineer, musician, and MER team member and mission manager at JPL.Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

As June transitioned to July, Opportunity was busy working on her analysis of Grasberg, at the north end of Cape York, part of the Shoemaker Formation along the rim of Endeavour Crater. Her energy was high – upwards of 575 watt-hours – and the skies were mostly clear, with a Tau recording 0.34.

After grinding into Grasberg with her rock abrasion tool (RAT) in late June, the rover eased into the new month conducting an atmospheric argon measurement with her alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) and taking a few pictures on her Sols 2999-3000 (July 1-2, 2012).

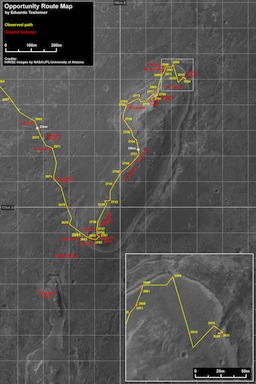

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

This route map shows Opportunity's travels up to its Sol 3024 (July 26, 2012), the rover's current location in Whim Creek at the northern end of at Cape York. This image was produced by Eduardo Tesheiner, of UnmannedSpaceflight.com, who created it from images taken by cameras onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. The rover will be quietly working in Whim Creek during the arrival of Curiosity, the Mars Science Laboratory rover, scheduled to set down on Aug. 5, 2012, around 10:30 pm Pacific Daylight Time.NASA/JPL-Caltech/UA/MSSS/E.Tesheiner

When the Sun set on Mars July 2nd, there was a cheer here, a marveling there, and a hip-hip-hooray on the other side of the Pond, as Opportunity checked off Sol 3000 on an expedition originally slated to last only 90 Martian days. The lack of any official acknowledgement or press release was pause for thought: do Earthlings already take rovers on Mars for granted?

Opportunity worked on, picking up her RAT on Sol 3001 (July 3, 2012) to brush the grind tailings from the target Grasberg. The rover switched instruments in order to take some pictures with her microscopic imager (MI) and then placed her APXS on the target for a long integration to try and determine what this rock was made of.

The rover devoted most of the rest of that first week of July – through the Independence Day holiday – and into the second week of the month continuing the APXS analysis of Grasberg, with integrations on Sols 3002, 3003, 3004, 3006, and 3007 (July 4, 5, 6, 8 and 9, 2012).

As the second week of the month began, Opportunity conducted some additional close-up imaging with her MI on Sol 3006 (July 8, 2012). With that, her work at Grasberg was done, and Opportunity hit the road again on Sol 3008 (July 10, 2012), driving for about 32 meters (105 feet) in search of more gypsum veins or whatever else she might find.

Turns out, Grasberg is "very similar to Deadwood," informed Arvidson. "It's the Bench material and it has a whole lot less sulfur than the surrounding Burns Formation. I think it represents the first sedimentary unit to form after Endeavour the crater formed and the rim was eroded down a little bit. Grasberg material probably shed from Shoemaker Formation, but it's a sedimentary unit, not impact breccia."

On Sol 3010 (July 12, 2012), Opportunity drove 55 meters (180.44 feet) to the south toward a small impact crater, named Sao Gabriel. "There are three little craters about one-third the size of Odyssey, which is about 20-meters in diameter, and we wanted to do a drive-by shooting," said Arvidson. "They were interesting enough for a drive-by shooting, but we planned to stop only if we saw interesting rocks, targets of opportunity in the ejecta or if imaging the wall could tell us anything new."

Sao Gabriel, however, is just not very big. "So it didn't excavate a whole lot and it's a little eroded down," Arvidson said. "It was worth the drive-by shooting, but not stopping. So we did a side-step to Sao Gabriel, and then went off to the northeast to Whim Creek," said Arvidson.

Opportunity almost seemed anxious to pick up the pace. The rover had been unable to drive for much of June, not because of a lack of power – the winds of the Martian spring have been particularly favorable for the rover this season – but because the MER's main communication link, the Mars Odyssey orbiter, had gone into safe mode. It then had to switch out of its reaction wheels [with which it routinely stabilizes itself in orbit]. That meant the rover could not downlink data except through a very small 'pipeline' via her X-band direct to Earth. And that meant the rover was unable to drive.

Just before Opportunity got going again, Odyssey once again put itself into the precautionary, Earth-pointed status called safe mode, this time after performing a maneuver to adjust its orbit. The spacecraft remained in this state for 21 hours before mission managers began recovering normal operations, according to NASA officials.

MER mission operations team members responded immediately to the absence of relay support from the orbiter, converted several rover X-band sessions with the DSN to Direct-to-Earth passes to receive the necessary telemetry for the team to assess the health of the rover. Opportunity was fine. And so, while Odyssey was in recovery, the rover was forced to slow her pace again in July, tasked only with a modest photometry campaign, daily observations of atmospheric opacity and other low-data volume remote sensing.

The good news was that the orbiter was only out of communication relay service for one week this time, instead of nearly three weeks as in June. And it was good news for Curiosity, as well as Opportunity.

In addition to conducting its own scientific observations, Odyssey has served as the primary communication relay for Spirit and Opportunity and NASA plans to use both it and the newer Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) as communication relays for Curiosity during landing and its two-year primary mission on the surface. That means Odyssey is still very much a critical part of the communication network at Mars and a vital link in the seamless relay of data to Earth.

During an MSL / Curiosity news conference on July 16th, NASA officials confirmed that Odyssey – which was to provide a near-real-time communication link with Curiosity on landing – would in its present orbit arrive over the landing area about two minutes after Curiosity landed. Even as the press conference was being held however, Odyssey's operations team was busy with the calculations and commands for an orbital repositioning maneuver.

"Odyssey went into safeing and that changed the orientation, which changed their drag, which slowed them down in their orbit, and consequently they were about six minutes behind where they expected to be," Nelson explained yesterday.

MSL can send limited information directly to Earth as it enters Mars' atmosphere. But, before the landing, Earth will set below the Martian horizon from the descending spacecraft's perspective, closing off that direct route of communication. The two other Mars orbiters, NASA's MRO and the European Space Agency's Mars Express, also will be in position to receive radio transmissions from the MSL spacecraft carrying Curiosity during its descent, but those orbiters will be recording information for later playback. Only Odyssey was to have been in position and prepared to relay immediately.

"Odyssey has been working at Mars longer than any other spacecraft, so it is appropriate that it has a special role in supporting the newest arrival," noted Mars Odyssey Project Manager Gaylon McSmith of JPL. Indeed.

Opportunity waited out Odyssey's safeing and recovery in fine form. Everyone on MER and MSL knows things could have gone differently. It is Mars, after all. Whether acknowledged out loud or not, team members on both missions are looking at the old workhorse orbiter with a newfound appreciation for its often unheralded but hugely important role in Mars exploration.

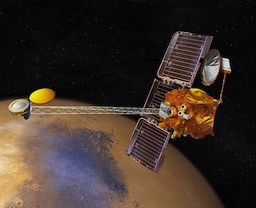

Odyssey

Mars Odyssey, which has worked at Mars longer than any other spacecraft, is the main data relay link for Opportunity and an unsung "hero" among Mars spacecraft. When the orbiter went into safe mode in June, and then again in July, the Mars Exploration Rover mission was slowed, but the orbiter is back in service relaying Opportunity's data and will be ready to cover Curiosity's landing on Aug. 5, 2012.NASA/JPL-Caltech

Meanwhile, Malin Space Science Systems' Mars Color Imager (MARCI) instrument onboard MRO began observing a dust storm near Endeavour Crater on July 13th, while Opportunity was taking a routine measurement of atmospheric argon with her APXS, part of a mission-long study.

The storm would never get any closer than 360 meters (0.22 mile) to Opportunity, but it elevated the atmospheric opacity over Endeavour. Within a couple of days, the MARCI team reported that they could see water-ice cloud cover around the site, something that indicated the dust storm was abating. [Water-ice nucleates on the suspended dust particles.]

The dust the storm wrought lingered, not surprisingly, and atmospheric dust in the region increased the haziness of the skies overhead. "There was a storm to the west of Endeavour Crater," confirmed Callas. "The effect on us is that it elevated Tau to 0.571, but Opportunity did get a small cleaning event, perhaps related to this storm, around the same time."

So, although Opportunity's power levels dropped mid-month from the high 500s to the low 500s in watt-hours mid-month, the rover and her team were not terribly concerned, and her solar array dust factor was maintaining a good level of 0.707.

But July 18th, normal UHF communication relays with Odyssey were restored and Opportunity was able to drive again. On Sol 3019 (July 21, 2012) and the robot field geologist logged some 42 meters (over 137.79 feet) driving in a kind of "V" trajectory, first to toward the small impact crater named Sao Gabriel for mid-drive imaging, then a near reverse drive away, back toward the south and the geologic cut called Whim Creek.

Two sols later, Opportunity drove across Whim Creek with a 10.52-meter (34.45-foot) jaunt toward some surface targets. The next Martian day, Sol 3022 (July 24, 2012), the rover collected a series of pictures for an MI mosaic of the target Mons Cupri before placing her APXS down on the same spot.

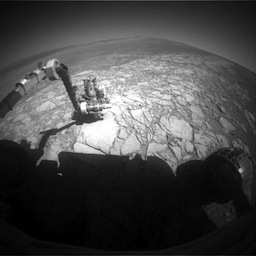

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell/ASU/S. Atkinson

Behold Whim Creek

Opportunity took the pictures that went into this image in July. Stuart Atkinson processed into this black and white panorama for the MER Update this month. For more of Atkinson's work, visit his Road to Endeavour blog at: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.comOpportunity was to have driven on Sol 3023 (July 25, 2012), but "the master sequence did not get onboard because of a link/margin problem," said Nelson. So the commands were re-sent and the rover drove for 6.05 meters (19.84 feet) on Sol 3024, slightly to the west to a parked position right in the middle of Whim Creek. And that's where the Mars Exploration Rover is right now.

Last week, on July 24th, Odyssey performed a correction maneuver, with a spacecraft thruster burn lasting about six seconds, to successfully nudge Odyssey about six minutes ahead in its orbit, which will put it in a position to provide prompt confirmation of Curiosity's landing. Thus, it now appears that Odyssey will arrive over Curiosity and Gale Crater 25 seconds early well within its +/- 60 second tolerance. So Odyssey is good to go for Curiosity's EDL.

For MER, that orbital correction threw off all Opportunity's communication windows by six minutes. "So we did another update to adjust the comm windows and they are now at the proper time," said Nelson.

"We've had our issues with telecomm recently," sighed Squyres. "It's just part of being at Mars with old spacecraft in orbit."

No question, the best news for every Mars explorer right now is that Odyssey, an unsung hero among planetary spacecraft, orbits on, ready to serve as the link for Opportunity and Curiosity, and now on orbit to be in the right place at the right time to relay confirmation of Curiosity's landing as originally planned. That confirmation is expected to be picked up on Earth at JPL by 10:31 p.m. PDT on August 5th.

The action never stops on Mars it seems and on the very next Martian day, July 25th on Earth, the MARCI team spotted another storm not too far from Opportunity. Again it abated, this time even more quickly than the first. Even so, MER eyes are on the skies over Endeavour. "In planning for the stand-down, we're taking the opacity into consideration, along with whatever the MARCI folks tell us about what weather systems might be emerging," said Arvidson.

Opportunity spent this past week sitting in Whim Creek and now as July comes to a close, the rover's has 34.64 kilometers (34,639.45 meters 21.524 miles) on her odometer. Her power levels are back up to 543 watt-hours, the Tau has dropped a bit to 0.665, and the dust factor is holding around 0.718. As annoying as that colloquialism is, it's all good on Mars right now.

During the coming stand-down, the rover will be conducting a pretty thorough study from its parked position in the middle of this fracture that cuts through the Bench bordering Cape York. The scientists will analyze the data returned to tell the story of how the Burns Formation of the Meridiani plains relates to the ancient environments at Endeavour.

"It's a good spot," Squyres said of Whim Creek. "We had hoped that this would give us a good view through the stratigraphy, and it seems pretty good. We've only seen some of it with Navcam. We need to get some Pancam images on it and that's in today's plan, so we'll see what we see. It's business as usual at Mars," he said.

There is an obvious rationale for MER to stand-down for Curiosity's EDL. "They're trying to make sure no other spacecraft is going to compete for attention with MSL – and by that, I don't necessarily mean anyone else would try to 'steal Curiosity's thunder,'" said Nelson. "The idea is to preclude any possibility that MER could have some kind of anomaly, for example, that required the use of uplink resources to try and resolve. By having Opportunity be fairly quiescent, that won't be of any concern."

Truth told, the MER team still has a couple of tracks still on the DSN schedule. "But we'll probably end up not being able to do anything with them or we may hold them as contingencies in case something happens," said Nelson. "Although I think if anything did happen, the more likely directive is to live with it until stand-down is over."

The MER uplink team does get a break for the next week and a half, but Opportunity's mission continues with a UHF downlink from Odyssey everyday. "One reason we get the downlink is to act as a 'keep alive' communicator for MSL, a demonstration, in other words, that Odyssey is still working." And – no one on MER is complaining about that.

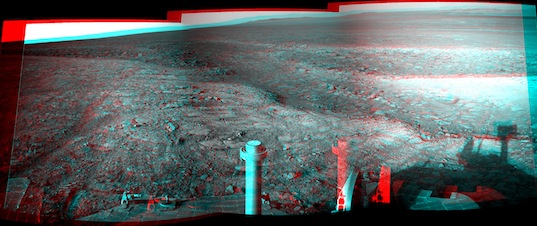

The rocky layers of Whim Creek

Opportunity took the images for this picture in July with her Pancam. The picture here was processed in approximate Martian color. The rover will be hunkered down in Whim Creek checking out the layers and trying to define the basal unit that formed over the Noachian Period terrain at the rim of Endeavour Crater.NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell/ASU/S. Atkinson

Opportunity's scientists are looking to record all the data needed to straighten out the "stratigraphy issue," as Squyres called it, at Whim Creek and Meridiani Planum. "One idea is that the Bench is the oldest sedimentary rock that formed right after Endeavour formed as the groundwaters were coming up, and the Burns Formation is the thick sequence of stuff that formed afterward – that's what most people think," said Arvidson.

"But another possibility is that this Bench material is sitting on top of the Burns Formation." This is not the most population notion. The confusion arises because the Burns Formation layers appear to be below the Bench in Whim Creek.

"The story seems to be that the Burns Formation is on top of the Bench material, but it just happens to be topographically below the Bench in this little fracture, because the fracture is a kind of down-drop block, and it down-dropped some of the overlying Burns Formation, protecting it from erosion. I think that's what we'll conclude," Arvidson suggested. "That's what we're trying to sort out with these experiments."

With the work at Whim Creek, the greater geologic story of Endeavour is beginning to crystallize. "There's the ancient crater terrain that was highly dissected by river systems, and Shoemaker Formation, the rim of Endeavour Crater, is part of the ancient crater terrain's surface.

"You can imagine back in the Noachian day, Mars was forming craters and channel systems, and there was snowfall and maybe rainfall, and a lot of erosion and a lot of material transported to the plains to the northwest," Arvidson said. "And then that pretty extensive erosional regime kind of slowed down. It became more sluggish and the region moved from being an erosional regime to being a depositional regime."

Geologic riches hidden in Endeavour

This map reveals the locations where the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) onboard MRO detected clay minerals at Edeavour Crater. This crater is about 22 kilometers (14 miles) in diameter. As indicated by the scale bar of one kilometer (0.6 mile), this map covers only a small portion of the crater's western rim. A discontinuous ridge runs north-south, exposing basalt (coded blue) and clay minerals (coded green) believed to be from a time in Martian history before the deposition of sulfates on the portions of the Meridiani Plains region that Opportunity has seen during its first 7.5 Earth years on Mars. Opportunity and soon Curiosity will be on the hunt for clay minerals.NASA/JPL-Caltech/JHUAPL

After an extensive amount of erosion, including an eroding part of the rim of Endeavour, "the whole environment moved from a kind of fluvial system or river system transporting a lot of material downslope, to a much gentler environment with rising groundwater and the first units, the basal units formed, what is now the Bench material," Arvidson continued. "The Bench material seems to be a nice mixture of Shoemaker Formation and a little sulfur and a lot of chlorine, and so it represents the basal or bottom unit of the sedimentary section that's sitting on top of the Noachian. It's nicely exposed, because it's hard, and it stands as a Bench today because of differential erosion surrounding Endeavour's rim segments."

Repeated groundwater rising events then led to the formation of the next unit, the layers that are the Burns Formation. "Then Mars shut down and wind erosion and cratering started. Eagle and Victoria and Santa Maria and Endeavour all punctured into the top of the Burns Formation . . . and then we landed," suggested Arvidson. "As we drove over to Cape York, we went from the Burns Formation to the Bench material and onto Cape York and the Shoemaker Formation."

Odyssey Crater, he added, punctured into the top of the Shoemaker Formation, and "represents the ejecta that we first measured last August when we went over to Cape York and Shoemaker Formation," Arvidson said.

Of all the past environments Opportunity has explored in her 8.5 years in Meridiani Planum, "Shoemaker is the oldest, then came the Bench material, and then the Burns Formation, which is now hundreds of meters thick and unconformably overlies this ancient crater terrain and Bench unit," Arvidson theorized. Time – and Opportunity's work – will tell.

As July turns to August, Opportunity chalks up another month of roving Mars hunkered down in the middle of Whim Creek, conducting some APXS analysis of a rock and taking lots of Pancam pictures of this trough to write this part of Endeavour's story.

"We're told to stand down for Curiosity's EDL, from -3 to +4 sols, but we're planning in chunks of 3 sols, so we're actually planning 9 sols in this stand-down period," informed Nelson. "We could basically use one of those sols as contingency to wrap-up of anything we absolutely have to do before we start stand-down, and we could use one, on the 8th sol, to drive again, but that doesn't mean we will."

"We'll finish off at Whim Creek after the stand-down and then head south looking for an extensive outcrop on the inboard side of Cape York," said Arvidson. "We're heading for the Noachian outcrops."

The MER team is not exactly sure where Opportunity will begin the hunt for the phyllosilicates, but Arvidson expects the rover will find a place sooner rather than later. "Further south at Cape Tribulation, there are big outcrops, big enough for CRISM to see a spectral signature of the clay minerals, but it's the same geologic setting as the inboard side of Cape York," he explained. "So we'll be driving south, looking to the west at the inboard rocks, and stopping where we think there is a good extensive exposure. About halfway down toward the southern edge of Cape York is the likely place we'll stop to do IDD work."

Side by side

This picture shows a life-size working model of the Mars Exploration Rovers (left) next to the Mars Science Laboratory Rover Curiosity (right), along with a couple of their caretakers at the Jet Propulsion Laboraotry (JPL) in Pasadena, CA, where all of the Mars rovers to date have been "born."NASA/JPL-Caltech

In the meantime, the MER team members will be keeping an eye on the weather. "It's another component in terms of planning to make sure we're on the other end of this stand down," said Arvidson, who is also a member of the Curiosity science team.

"You don't need to worry about us," assured Callas. "All the attention is now on MSL and we're all pulling for her – or is it a he?" he wondered out loud. It's a bigger bulkier rover, not as svelte and elegant and symmetrical as the MERs, so Curiosity, for many, seems to be of the male persuasion.

In any case, no matter the robogender, Curiosity is a much more complex vehicle. While many MER team members are also a part of or shifted to the Curiosity mission, everyone deep down inside does seems truly excited about the arrival of the "new sibling." And, sibling rivalry aside, why wouldn't they be?

"If standing down for Curiosity is the worst frustration I have to deal with in my life, I'm doing real well," chuckled Squyres. "I'm thrilled to be watching and thrilled to be a small part of it, and we are all wishing MSL and Curiosity the best."

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth