A.J.S. Rayl • Jul 31, 2008

The Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Spirit Bides Winter Time, Opportunity Wraps Victoria and Begins Exit

After cruising through winter solstice in late June, the Mars Exploration Rovers (MERs) roved into July taking every advantage of a winter that is by all appearances now proving to be rather mild for the Red Planet. At Gusev Crater, Spirit managed to maintain its power level and get back to doing a little bit of science, while on the other side of the planet, at Meridiani Planum, Opportunity finished photographing Cape Verde and began to chart its course back to Duck Bay where it will exit Victoria Crater.

The MER team's decision to have Opportunity rove out of the big crater – which was only made during a science operations working group meeting Wednesday afternoon -- was the big news of the month. It came one week after the rover experienced a spike in the electrical current to the motor for its left front wheel, an event ominously similar to what Spirit experienced just before it lost the use of its right front wheel for good back in March 2006.

During a series of diagnostic tests this week, the wheel maneuvered just fine. "It seems to have been only a transient event," said Jake Matijevic, chief of rover engineering at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where the rovers were designed and are being managed. But, he added, "the high current spike has spooked the team a little bit in the sense that we're wondering – even though the actuator [motor] looks like it's okay – maybe this is a harbinger of some degradation on the mobility system."

"Because it looked so similar to the spike that we had just before the right front wheel failed on Spirit back on Sol 779, we were very concerned," confirmed John Callas, MER project manager, of JPL. "These wheels have around 24-25 million revolutions on them and their design requirement was 2.5 million so we're a factor of 10 beyond the requirement," he pointed out.

Spirit has fared remarkably well with its broken right front wheel for more than 2 years – and, because of it, serendipitously churned up one of the mission's most significant discoveries, nearly pure silica – but it wasn't and isn't constrained the way its twin is now. If Opportunity loses one of its front steering wheels at this point, chances are it would be stuck inside Victoria Crater for the rest of its life.

"We've always been concerned that if we lost an actuator inside the crater, we would never be able to get out. The slopes are just too steep for us to climb out at the same time we're trying to drag one of the wheels like we do with Spirit," Matijevic said.

Not surprisingly, the team decided without much debate that it was time for Opportunity to rove on and out of Victoria. "We want to get out of the crater as quickly as possible," Callas said during an interview right after the meeting.

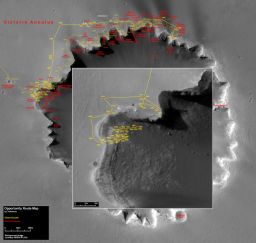

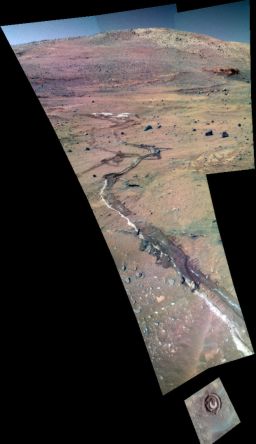

Opportunity's routes

Opportunity's routesEduardo Teishner has detailed Opportunity's routes up to the rover's Sol 1584 (July 8, 2008) over this image of Victoria Crater, taken by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO.) Credit: NASA / JPL / UA / E. Teishner

The plan is for the rover to exit the crater the same way it entered, by way of the shallow slope at Duck Bay. Because of the sandy, slippery slope it has to navigate, Opportunity's departure is going to take some time, Callas said. "It's going to be as direct a route as we think we can achieve, but we still have to deal with the slope we're in," he noted. "We're not backing down, so out of the crater is up from where we are right now."

Today, the last day of July, its Sol 1607, Opportunity took the first drive to that end. It moved 24 centimeters (about 9.4 inches) and made a 5-degree heading change despite significant slippage of around 90%, according to Matijevic. "But there was no recurrence of a high current spike on the left front drive actuator," he said. Another drive is planned for this weekend.

Fortunately, Opportunity's got plenty of power for roving. Throughout June and July, small gusts of wind have cleared a fair amount of dust from its solar arrays, giving it levels that hover between 350-380 watt-hours, even with its current southerly tilt away from the Sun, reported Matijevic.

Spirit has not been so lucky. Its arrays are so thickly coated with the powdery dust now that it looks like it's wearing Martian camouflage. The rover's dust factor is 0.345, Matijevic said. That means only about 34% of the sunlight is reaching its arrays. But the rover's position on the northern edge of Home Plate, the circular volcanic formation it's been studying, has allowed it to maximize intake of the sunlight and maintain power generation averaging around 225-230 watt-hours throughout July. [The rovers each sported levels upwards of 900 watt-hours on landing in January 2004.]

"We have been able to maintain a stable battery state of charge, the heaters for the batteries and the Mini-TES [miniature thermal emission spectrometer] have been enabled the entire season, and now the Sun is starting to move south again," said Callas. Keeping those vital heaters going was the top priority this winter.

Spirit at Home

Spirit at HomeThis image shows Spirit at its current location on the northern edge of Home Plate in the Columbia Hills,at Gusev Crater. The picture was taken during the southern hemisphere winter solstice at about 2 p.m. local time on the rover's Sol 1591 (June 24, 2008). Home Plate is the elevated round and light toned mesa on the right side of the image. Spirit is visible at the large dark "bump" on the north-northeast edge of the circular volcanic formation. Mid-winter on Mars is the time of the clearest and least dusty atmosphere.

Credit: NASA / JPL / University of Arizona

The MER science team, as Steve Squyres, principal investigator for rover science, has previously noted in these updates, is anxious, come springtime, to use the mineral-seeking Mini-TES to search for more silica and whatever other Martian surprises may be lurking in the region. Once again, Spirit showed its right robot stuff, persevering and pulling through despite the odds.

Being able to maintain its power levels and the fact that the draw from the survival heaters fell slightly allowed Spirit to begin taking some atmospheric measurements and a few more pictures for the big Bonestell Panorama. "Spirit has been active, though at a low level in that we have had limited science operations each week," Callas affirmed. All things considered, the science completed this month was really, well – gravy.

While the power levels are expected to rise in August, Spirit likely will stay put for a few more months, Callas said. "We will increase the science as the power levels rise, but it'll probably be in this posture until the Sun starts getting closer to being overhead." There is a possibility it will rove as soon as October, he said, but the team has still not decided whether the rover will move before or after solar conjunction, which begins at the end of November and lasts to mid-December. Obviously, that decision will depend on how much more power Spirit will be able to generate in August and September, as well as other factors.

So far this winter, Mars has been cooperating and even, in a way, seems to be giving the two robot field geologists something of a break. "We were hoping for conditions like this and it's worked out that way," said Matijevic. "There have been instances during the previous winters where we've had little up-spikes in the tau or amount of dust in the atmosphere or other changes in the general atmosphere or environmental condition around the vehicles in wintertime. This season has been unusual in the sense there hasn't been any of those and I've generally thought of us as being fortunate that the weather has held as well as it has."

Although the newfound urgency to get out of Victoria Crater puts the spotlight back on Opportunity, Spirit's resilience through the MERs' third Martian winter is something to underscore. It certainly will be in the space history books.

"Past winter, Spirit and Opportunity still have exciting adventures ahead," said Callas.

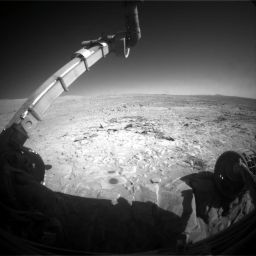

Intrepid defined

Intrepid definedIf you've ever gotten stuck while driving on a sandy beach or road, you can imagine Opportunity's recent experience trying to get to a place called Nevada on Mars. At times, the rover's wheels have done more slipping than advancing. At one point this past month, a potato-sized rock nearly got lodged in one of its wheels, but, true to its MER nature, Opportunity keeps on keepin' on, heeding the advice of Winston Churchill -- never, never give up.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

The MER science team has long had its sites set on their next destinations: Spirit will head to the formations called Goddard and von Braun, named for the pioneer rocketeers, looking for more of that nearly pure silica it found last year along the way.

After roving out of Victoria Crater, Opportunity will begin a study of the cobbles on the Meridiani plains. Then, it may head for another [as yet unnamed] crater about 2 kilometers (about 1.2 miles) to the north/northwest of Victoria, Callas offered, provided of course that all revolves well with its left front wheel.

The twins have gone for so long now, it sometimes seems as if they'll rove on forever and while there are certainly a lot of people around the world who could get behind that dream, Spirit and Opportunity are aging. By rover standards, however, they're "senior citizens," according to Larry Soderblom, who is standing in as acting principal investigator while Squyres takes leave for this year's Arctic Mars Analog Svalbard Expedition (AMASE) in Svalbard, Norway, one of the places on Earth that is somewhat like Mars. Nevertheless, optimism about the futures of Spirit and Opportunity remains high.

"These rovers are about 100 years in rover years, but who knows," Soderblom mused, "maybe they'll live to 200. The fact that they're still making such significant discoveries deep into their missions sort of says – don't give up on these missions when they're halfway through," he said. We need to keep the funding there to let them get all the fruits they can."

Spirit From Gusev Crater

As June turned to July, the story at Gusev Crater continued to be all about power and survival. For the most part, Spirit spent the month biding its time, continuing to ride out the winter.

The reason Spirit has struggled in a way Opportunity has not is two-fold: location and the global dust storms of 2007. Because of its location and the position of the Sun in the sky at Gusev during the winter season, the solar-powered rover must park each winter on a slope that allows it to tilt its solar arrays to the north to catch as much "fuel" as possible from the winter Sun.

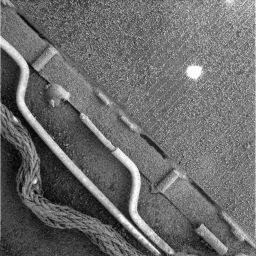

Got dust? You bet.

Got dust? You bet.The global dust storms of June-July 2007 left a Sun-blocking haze in the atmosphere and a thick sunscreen of particles on Spirit's solar panels. As the Martian winter set in and the skies cleared after the storms, more and more dust fell and so far this rover has not been graced with any clearing wind gusts.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / USGS

At the beginning of the mission in 2004, the assumption was Spirit would not survive even the first Martian winter. Once it landed, however, the MER team saw the small range of hills in the distance, which they named in honor of the crew of the Columbia space shuttle that disintegrated on its return from space in February 2003, and decided to send their charge in that direction.

Despite the challenges of the rock-strewn landscape at Gusev, Spirit managed to make the some 2-kilometer journey to the Columbia Hills, where it began its hike up Husband Hill to beat the odds, survive the rovers' first winter season – and become the first rover ever to climb a Martian "mountain."

For the second Martian winter, the plan had been for Spirit to hike what turned out to be the even taller McCool Hill, but en route the rover experienced that high current spike and lost the use of its right front wheel, making a second ascent impossible. Instead, the rover turned around and valiantly drove backwards, dragging its broken wheel to a place near McCool called Low Ridge, drawing cheers from team members and fans everywhere. For some seven months, it hunkered down at that haven and held on through the brutal cold of the dreaded season.

With all of the dust fallout from the global storms of 2007, however, there was serious doubt about whether or not Spirit could make it through yet another Martian winter. The storms left a haze in the atmosphere and a thick coating of particles on Spirit's solar panels. As the nights grew longer and the days colder with the onset of winter, the dusty coating got thicker as more and more dust fell from the sky.

To conserve energy, rover planners cut back on communications and the amount of time the rover was "awake," as has been reported here in the last several updates. Remarkably, Spirit's lowest levels of power never dipped much lower than 200 watt-hours, not even close to the 128 watt-hours that Opportunity experienced during the dust storms, which remains the lowest rover power level on record.

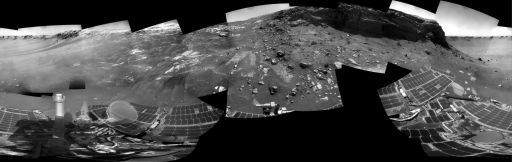

Fragment of Spirit's McMurdo Panorama 2006While parked at its winter have at Low Ridge in 2006, Spirit worked on capturing the largest panorama taken on the mission to that date: a 360-degree view of the surroundings through all 13 filters at very high resolution. This fragment of the McMurdo Pan consists of 16 individual frames captured from Sols 856 to 869 (May 31 to June 11, 2006). Although the view is through the rover's red, green, and blue filters, it is not correctly calibrated, making the sky appear blue and enhancing color variations in rocks and soils.

Fragment of Spirit's McMurdo Panorama 2006While parked at its winter have at Low Ridge in 2006, Spirit worked on capturing the largest panorama taken on the mission to that date: a 360-degree view of the surroundings through all 13 filters at very high resolution. This fragment of the McMurdo Pan consists of 16 individual frames captured from Sols 856 to 869 (May 31 to June 11, 2006). Although the view is through the rover's red, green, and blue filters, it is not correctly calibrated, making the sky appear blue and enhancing color variations in rocks and soils.Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell / Midnight Mars Browser

As the MER luck would have it, the northern edge of Home Plate has proven to be a choice winter hang-out, because Spirit has been able to tilt its arrays there to 29.9 degrees to the north where the Sun is in the sky. "We got to the right tilt angle for the vehicle so we can maximize the energy production," said Matijevic, "and we've been taking advantage of that ever since."

Even so, the MER team had no choice in June but to put all science on hold, including the routine atmospheric and dust monitoring measurements. Simply surviving and maintaining the tiny heaters for the rover's main power batteries and the mineral-detecting miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES) became the priorities.

Where Opportunity gained energy in June and July, in large part because little gusts of wind cleared some of the dust from its arrays, Spirit hasn't seen so much as a breeze this season and its arrays are now so thickly coated in the powdery Martian dust that it is only able to access about 34% of the sunlight that is beaming down on Mars. But that wasn't about to stop this rover.

Showing the same kind of mettle the MERs have been demonstrating since they landed, Spirit managed to rise to the challenge on about the same amount of energy that it takes to run a microwave oven for seven minutes each day and not only survive through winter solstice on June 26, but emerge power positive.

"We rode out the winter solstice with power levels around 225 watt-hours and the rover was able to maintain that level throughout July," Matijevic said. The rover's two batteries, which provide about 22 amp hours when fully charged are currently charged to 19-19.5 amp hours, he added. Meanwhile, the survival heating for the Mini-TES and for the batteries this past month was "no worse than about 80-85 watt-hours or so," he added. That left Spirit with enough power to begin adding science back to its agenda.

"We have gone to a twice-weekly planning cycle – on Monday and Fridays we have our planning days for the rover," said Callas. "We are doing 3-sol and 4-sol plans for Spirit, minimizing communications sessions to save as much energy as possible. The UHF downlinks are every 4 days, and the X-band uplinks are 3 and 4 days, so the two will fall out of phase with each other."

Spirit has been working for about a half-hour each of those two sols in those planning cycles. During its work sessions, the rover has been taking atmospheric measurements, mostly dust monitoring, and some more images for the Bonestell Panorama, the full-color, stereo 360-degree panorama from its location at Home Plate. "We've gotten about half of the Bonestell Pan finished, so we still have quite a bit to do," said Callas. "But the part that has been mostly completed is the portion of view in front of the vehicle, basically looking at Home Plate and it does look spectacular."

Still blending in

Still blending inSpirit's deck began getting coated way back in September-October 2007, as dust from the global storms of June-July rained down from the sky. This approximate true-color image was assembled from frames taken by the Pancam from the solar-powered rover's Sol 1355 to Sol 1358 (Oct. 26-29, 2007). It shows the best view of the deck, though it somewhatdistorts the ground and antennas. The eight-pointed star shape near the front of the rover (bottom of image) marks the location of the camera mast, which is out of view of the Pancam, which sits atop the mast.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

In addition to the science, the engineers have been trying to synchronize Spirit's clock. Like your watch or clock at home, the rovers' clocks can lose or gain a few seconds each month. Normally, this routine maintenance is done in a direct-to-Earth (DTE) transmission in which time packets are sent up, These time packets give the engineers the ability to correlate the rovers' clocks with real time on Earth. Since Spirit doesn't have the energy it needs to do that right now, "the best we can do is estimate," said Matijevic.

To acquire a good estimation, the engineers have been trying to 'beep' through the X-band in order to determine how much the clock has drifted. "Our estimation process is to take one of these carrier signals, which is our beep, which corresponds to a time on the spacecraft that we can measure from the spacecraft's event logs," said Matijevic. "We can then do a rough correlation of the difference between the Earth time there and the Earth time we can calculate from the onboard clock. Looking at that difference basically gives us a correction time for the amount of drift that clock has seen over time."

Attempts to beep through the X-band on Sol 1604 (July 7, 2008) were not, however, successful. It turns out that there is so much activity onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) that the "noise" emanating from that orbiter "swamps out our signal," Matijevic explained. So, on Sol 1611 (July 14, 2008), the engineers tried to beep when MRO was behind Mars so some of that "noise" from the oribter would be blocked. "We got part of the signal, but we didn't get all of it at the end, so we couldn't do a good time estimate based on the receipt of the signal."

Since Spirit probably won't have enough energy to support a DTE transmission for several more months, the plan, Matijevic added, is to just keep trying to complete the estimation. "These beeps are a mechanism for doing something in between and we're just going to continue to try periodically."

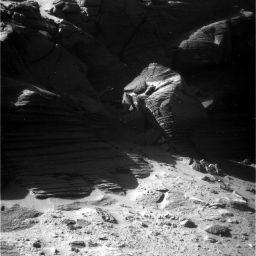

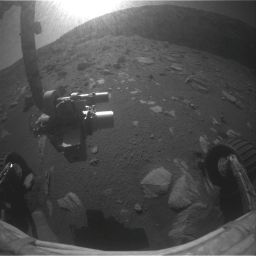

Hunkered down

Hunkered downSpirit snapped this picture with its front hazard camera on Sol 1506 (Mar. 28, 2008) from its parked position off the northern edge of Home Plate. The rover is styill in the same place and will stay in this position until the Sun begins to get higher in the sky and it can increase the amount of sunlight fuel it can access.

Credit: NASA / JPL - Caltech

So far, the drift in Spirit's clock hasn't caused any real problems, Matijevic said. Nevertheless, the team does like to keep its time reference as closely in sync as possible and in situations like this their experience really pays off. Over the years, they've found that during the course of a month there may be "30-40 seconds of drift between the reference time here on Earth and the reference time we can calculate on the vehicle," said Matijevic.

"We'd like to take that time out though, because if there's ever an instance where we're trying to do real-time operations with the vehicle, then we've got to know when to send commands, when those commands will be received, and when we'll get back a signal from the vehicle. The precision also helps in being able to perform a recovery action, he added.

"That 30-40 seconds can have a significant impact, especially when we're trying to time a series of events to take place over the course of just 30-40 minutes," Matijevic continued. "Our real-time windows are not open for much longer than that now and if we're trying to send a signal, counting for one-way light time that's more than 10 minutes now, and we're trying to get a few things done within that period, those 30-40 seconds can really add up. In the past, what we've seen is when we don't quite get the timing right – when we send commands at a time when the vehicle isn't listening or we send it early and the vehicle hasn't started in the communication window – then all those sequences tends to get fouled up," he noted.

"A lot of what we do [with the engineering] is anticipatory. We try to plan as though we're going to have a problem and we try to set the stage so we can recover from those problems," Matijevic explained. "Doing regular maintenance to make sure that we can respond and respond correctly when we have to is part of our general agenda with respect to both vehicles. In Spirit's case, we just haven't had the chance to be able to do this kind of correction on the clock."

The Art of Chesley Bonestell

The Art of Chesley BonestellThis image shows the dust jacket cover of The Art of Chesley Bonestell by Ron Miller and Frederick C. Durantt III, published by Collins & Brown Ltd, 2001. Arthur C. Clarke, who wrote the forward for the book, defined Bonestell's impact as "colossal." Credit: Collins & Brown Ltd.

Despite a not-exactly-synchronized clock, Spirit and its team carry on. The rover will basically spend August the way it spent July, riding out the winter season. "But as the power increases, we will add in more science activities," said Callas.

Spring won't "bloom" in Mars' southern hemisphere until January, but it's is possible that Spirit could be roving again as early as October. "The question will be whether we move before or after solar conjunction, a two-week period that begins in late November," Callas said. During those two weeks, the rover will be on its own, "because of the solar corona affecting the uplink," dropping out or even scrambling the data.

In any case, as soon as energy permits, Callas said, Spirit will begin roving south to the features called von Braun and Goddard. "Remember, it was in this area where we found the high silica. The expectation is that there is more rich silica to be found and the route to Goddard and von Braun will take us through some of these low-lying areas between ridges where we think the silica would have accumulated. So we have a lot of excitement in store for us with Spirit as soon as we start driving again with her."

While the past few months have been slow and an expected source of some frustration, Spirit remains healthy and the future is once again looking bright -- and who could ask for more than that?

"We have a vehicle that maybe is 120 meters away from some new geological formations there and if it had another 100 watt-hours of energy we could start driving over there," Matijevic said. "But for now, we have to wait."

The MER team knows well that patience can be the better part of valor on Mars, as it often is on Earth. Like always, however, the waiting is the hardest part.

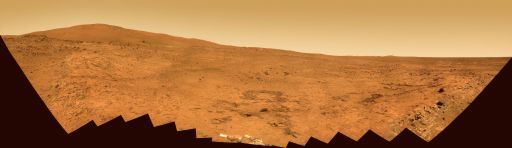

The Bonestell Pan so far

The Bonestell Pan so farAlthough the chill and low Sun of winter sharply limit the science activity of Spirit, the rover has slowly and steadily been acquiring images for a 360-degree panorama from its parking spot on the northern edge of Home Plate. As of July 16, 2008 the rover was about halfway done with the panorama named for the late, great, legendary space artist Chelsey Bonsetell. This image, which represents about 120 sols of work for the rover, was taken from the Martian Chronicles weblog, where it can be downloaded at its original resolution. Note: The color in the version shown here has been tweaked slightly by Astro0.Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

At the end of June, Opportunity used its panoramic camera (Pancam) to begin taking a series of high-resolution and super-resolution images of outcrops dubbed Alpha, Bravo, Charlie, Delta, and Echo from near the base of Cape Verde inside Victoria Crater and during the first week of July, the rover completed that assignment.

Down on Earth, MER science team members have been analyzing all the Pancam images of Cape Verde as they arrived. "The whole point of being at Cape Verde and doing high-resolution and super-resolution imaging is that this was our first chance to get close up to one of these capes or promontories to better understand these rocks that we've been seeing from a distance [since September 2006] with images that give us information about texture and what the individual layers are," said Alexander Hayes, a grad student at Caltech.

Working under John Grotzinger, professor of geology, and Oded Aharonson, associate professor of planetary science, Hayes, along with fellow grad student Lauren Edgar, has been working on the planning and interpretation of these up-close and "personal" images of Cape Verde. From their analysis this past month, the group has been able to refine and fill in some of the blanks in their scientific interpretation of just what the straitgraphy or layering in Cape Verde is telling them about the paleo-environment in the Meridiani region.

The team has known for a while that Victoria Crater is an ancient Aeolian dune field, eroded by wind blowing from north to south. "The rocks themselves are telling us they are hardened, sinuous crusted dunes," noted Hayes. "What surprised us was how complementary the capes were. When we went from one to another, we realized we were looking at different parts of the same overall feature. What we see at Cape Verde is the same as what we see at Cape St. Vincent and Cape St. Mary -- crossbedding indicative of a dune field. You look at one cape and you see what you'd expect to see if you sliced into the dunes at that angle, then go to another one and at that angle you see exactly what you'd expect, so you're looking at this regional dune field that's expressing itself in glorious detail on Mars. By getting up-close, we knew we could start distinguishing the textures and how exactly the sand was falling to create the layers."

In fact, the highly detailed photographs have taken the group vicariously right to Cape Verde. "For the first time, we're doing things that would normally be done by a field geologist on Earth, only we're doing it on Mars and at the same level of detail that a field geologist on Earth would. In other words, we're doing the same kind of analysis you would do if you were out in the field at Meteor Crater [Arizona], but we're doing it on Mars with a robotic field geologist," said Hayes, who first began working on the MER mission as an undergraduate in 1999, when the rovers were just pieces. "Because of the accuracy and level of detail that we're able to see in these images, we are now also able to build models that show the paleo-environment and what was going on. There's a wondrous story at Cape Verde with a lot of science we're still working on."

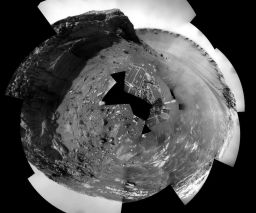

Polar view of Cape Verde base

Polar view of Cape Verde baseOpportunity took a series of images from its Sols 1600 to 1605 (July 25-July 30, 2008)with its navigation cameras and Eduardo Teishner assembled them into this polar version of the 360º panorama. North is to the left. The images was rotated, Teishner noted, for aestetic purposes.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / E. Teishner

The story of Victoria is still coming together, but already the exquisitely detailed Pancam images have allowed the group to answer long-held questions about the crater. The tri-layer light-toned ring that encircles the interior of the crater, which Opportunity began examining since last October, for example, is something that happened after the rocks were in place. "It's pretty clear that that bright band is an alteration of the rocks and not part of the depositional rock record," said Hayes. "Most likely the band was there before the impact that created the crater, but it may not have been. We can say that band was put in place after the rocks were in place so that band is the youngest thing at Cape Verde."

Even more exciting, arguably, is that after all the study of Victoria, the super-res images have at long last allowed science team members to home in on the boundary of the dune. "Just this past month, we finally found the bottom of that dune unit at Cape Verde and we did that from high-res and super-res imagery," Hayes said. "We've seen the base of the unit we're talking about."

And underneath that dune field?

"Another dune field," offered Hayes. "It might be either be a completely different dune field below it or it could be that the dune field we're looking at was part of a very, very large dune field. You can have dunes running on the back of other dunes, so it can either something like a 10-to-30-foot dune riding on back of a 100-foot dune field or it's another dune field from another time. It could be either answer."

While Hayes and crew were working on interpreting the data that Opportunity was sending down from Cape Verde and the rover was finishing up its super-res imaging assignment on Mars, rover engineers at JPL spent some time during the first week of July working on preparatory analyses, kind of troubleshooting in advance research. Specifically, they characterized the performance of the rover's rock abrasion tool (RAT) along the z-axis by comparing voltage and the speed of the actuator at different temperatures. In the event that the z-axis encoder lines break, as the encoder lines for the grind and revolve axes already have, this characterization will be essential in developing a functional strategy for operating the RAT with full, open-loop control.

"The two encoders that we have lost are actually on traces on the outside portion of the ribbon cable, which leads from the electronics down over the arm to where the RAT is located on the arm," explained Matijevic. "We think we're seeing a slow delamination or degradation of that ribbon cable and, unfortunately, the next traces in that cable ribbon are the encoder for the z actuator of the RAT." The z actuator supports the up and down motion of the RAT. " What we were doing is preparation for when we encounter that problem."

After returning hundreds of images that are stunning in detail, Opportunity completed its Pancam campaign at Cape Verde by the end of the first week of July. The robot field geologist then began what was supposed to have been a short trek to an area of outcrop that extended out from Cape Verde and was accessible on the slope. It was located just 3 to 4 meters (about 9 to 12 feet) away, behind a rock dubbed Nevada, so-named because it looks something like the shape of the state

The area was in the shadow of Cape Verde late in the afternoons, thus presented a possible energy problem for Opportunity. "But after careful measurement and evaluation, we felt we could drive there, do this work, then drive away," said Matijevic. The plan was to drive up the slope, then circle around to drive down the slope and into a position where the rover could get the instrument deployment device (IDD) down on the outcrop to carry out some close-up studies of that outcrop.

Sometimes though even the best-laid plans don't work out.

Opportunity took off for Nevada on Sol 1582 (July 6, 2008), but the going got exceedingly tough and it only managed to put a few centimeters on its odometer. "It was very slippery," said Matijevic.

"We were on a 20-degree slope covered with a lot of loose material and the rover was struggling just to make headway," expounded Callas. "We changed tact a couple of times trying to get to Nevada."

But the driving continued to be arduous. Since the azimuth joint on its shoulder – the joint that allows the rover's arm to move from side to side – froze a couple months back, Opportunity is now driving with its arm in a straightforward position, or fishing pole configuration, as some call it. "That makes it awkward to drive, because it's a risk to arm and it means you have to be more careful," said Soderblom, who was one of the science operations working group chairs during those difficult days. Add to that the sandy terrain that has caused the rover to slip, often as much as 90% on the slope inside the crater and the drives must be more cautious, "So progress was very slow going."

Opportunity logged subsequent drives on Sols 1584 (July 8, 2008), 1591 (July 15, 2008), 1593, 1596 (July 20, 2008), and 1598 (July 22, 2008), progressing just a few centimeters with each one. "Every one of these drives was intended to get us to this sort of staging area for the run to this Nevada region, but climbing up these hills has been very difficult," said Matijevic.

"We've been negotiating anywhere from 10 to 15-degree slopes for quite some time, but we've gotten stuck in a little dirt pits in the past, so we have been trying to stay on rock paths rather than driving through the dirt," Matijevic continued. "Even then, we're not always clear if the rocks are actually outcrop rocks or so lightly positioned in the soil they will move if you drive on top of them. While the path we took seemed to have more rock than sand, the vehicle was still slipping significantly as it was trying to get up the slope," he said.

Eventually the rover drivers tried to direct Opportunity across slope to get to a little less slippery path where the rover could get a little more traction. "They then could turn and position themselves at this sort of staging area," explained Matijevic. "That's what all these little drives were. They were each a few centimeters total, but the drives were all stopped because of high slip."

By the end of the third week of the month, Opportunity, for all its expended efforts, had only managed to drive halfway or about 2 meters toward the Nevada region and the outlook for making good progress was not looking great.

Then, a week ago, on Opportunity's Sol 1600 (July 25, 2008), as the rover was inching to the halfway point toward it destination, it experienced a spike in current from the actuator or motor that controls its left front wheel. "That stopped the drive," said Matijevic. And caused the MER team to take a step back.

"To remind you, when the wheel failed on Spirit, a few sols before it failed there was a current spike, then we had the wheel failure. So, we couldn't help asking – 'Is this current spike a precursor a foreshock to a catastrophic failure?'" said Callas.

This past week, rover engineers conducted a series of diagnostic tests on that actuator to determine why the current suddenly jumped. "We did a set of resistance tests on the wheel and we had normal continuity through the motor," said Callas. "We compared the expected resistance value for that motor to the resistance on the motor for the right front wheel and they matched," said Callas. "We then did a wheel wiggle just to make sure there wasn't some rock that we didn't see on the outside that maybe was caught in the wheel hub or something like that. The wheel wiggle looked to be just fine." [The engineers can't really see the outside of the wheels, but the hazard cameras can see the inside of the wheel.]

"Then we did a motion test of the left front wheel where we rotated it back 45 degrees and then rotated it forward 90 degrees keeping all the other 5 wheels fixed," Callas continued. "That behaved normally. The current levels were well behaved and the voltages were well behaved and the rate on the motor, forward and backward, so the wheel looks fine. But we don't know if this current spike was a wake-up call," said Callas.

"We've been very sensitive to high current spikes on actuators, ever since we lost the actuator on Spirit's right front wheel. On Spirit, basically we were driving along pretty much with nominal current, suddenly had this high spike, then no performance on the motor ever since. That thankfully hasn't been the case on the left front actuator on Opportunity," said Matijevic.

Opportunity has racked up more than seven miles on its odometer and in the last 4.5 years, the only other mechanical issue it's experience a 'jam' in the right front steering actuator back in 2005, on Sol 443. Interestingly enough, though, "the left front wheel on Opportunity has the most revolutions of any of the wheels. It's 25.3 million versus 24.3 million," Callas pointed out. "They were designed for 2.5 million revolutions."

When science team members met July 30, they quickly determined that Opportunity had acquired all the important science data they needed to get within the crater and it was time for it to rove on, especially given this scare with the wheel. "They decided that the science we would do out on the plains in Meridiani is the most important science to do so getting out of the crater is the priority," said Callas.

"Where we came in, Duck Bay, is where we're targeting to go out. That is the shallowest slope," said Callas. So, as July came to an end on Sol 1607, Opportunity took that first short drive, "just to check out the wheel in terms of normal driving, with all the wheels operating," Callas said. "We are on a path now to leave Victoria. The rover drivers have been looking at Victoria and how to get out and so we're going to start along that path, but it's going to be as direct a route as we think we can achieve. But we still have to deal with the slope we're in. We're not backing down, so out of the crater is up from where we are right now."

Since it has to go up slope, to go across slope and then down, Opportunity slipped about 90% of the intended drive, managing to move onward by only 24 centimeters (9.4 inches). But it did make a heading change of about 5 degrees and there was no recurrence of a high current spike on the left front drive actuator.

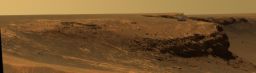

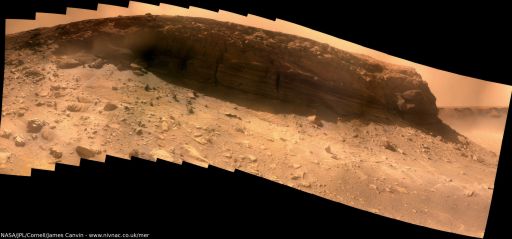

Cape Verde panorama from Opportunity

Cape Verde panorama from OpportunityOpportunity captured this breathtaking view of Cape Verde, from Sol 1570 to Sol 1578 (June 24 to July 2,2008 ) during a weeklong pause in its crawl toward the cliff. It is shown here at only half its full resolution; visit James Canvin's website for the full-resolution view.

Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell / James Canvin

Past that, Opportunity remains in excellent health, Matijevic said, sporting 350-to-380 watt-hours, plenty of power to rove on. "This is even with a southerly tilt of the vehicle, so everything is good in terms of energy," he added. Always the luckier of the two rovers, Opportunity has been gifted with small gusts of winds that have resulted in "small reductions in the dust coating over the last 2 months."

The next major destination for Opportunity is the cobble field out on the plains, as Squyres indicated it would be some months back.

"We're going to drive again across the plains of Meridiani and conduct this cobble campaign, looking at these exposed rocks lying on the surface that tell us about different places on Mars," Callas elaborated. "Then we're going to head toward another interesting feature, like another crater. There's a candidate crater [not yet named] about 2 kilometers to the north/northwest from our current location."

For now, the focus is on getting the rover off the slippery slope, out of Victoria Crater and back onto those plains.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth