Emily Lakdawalla • Jun 30, 2016

Juno's first taste of science from Jupiter

Jupiter is growing in Juno's forward view as the spacecraft approaches for its orbit insertion July 5 (July 4 in the Americas). The mission has released two views of Jupiter and moons taken about 7 days apart. This happens to be Ganymede's orbital period, so the three inner moons -- Ganymede, Europa, and Io -- are in nearly the same positions in the two photos. In the time separating them Ganymede went around Jupiter once, Europa twice, and Io four times. Hopefully, on Monday, NASA will release a movie with more frames connecting these two endpoints, and more! We're supposed to be seeing raw images from that movie released at the same time, too -- I'm trying to find out how and where we'll be able to get those. These photos are unusual because Jupiter appears at half-phase, and the stripes are not perfectly horizontal, because of Juno's polar trajectory. (The moons don't appear to be half-phase because they are not resolved -- they are just dots as far as the camera can tell.)

All the science instruments have been returning data on approach. At a press briefing this morning, the team showed some very early data from one of them, the plasma waves instrument, which has been measuring the solar wind during cruise and is now directly measuring Jupiter's magnetosphere. They crossed the bow shock on Friday, June 24 (where the solar wind slows to subsonic speeds as it's diverted around Jupiter's magnetosphere), and entered the magnetosphere itself on Saturday, June 25. Here the plasma waves data has been turned into sound, to help you sense the differences between solar and Jupiter environments.

At a press briefing that the mission held today, I asked about data from other instruments. The answer was that all the instruments have been gathering data and the science team is very happy, but it's going to take a while to understand what the rest of the instruments' data are telling us; only the JunoCam and Waves data were amenable to such a rapid turnaround for presentation. I think that is going to be the story of this mission. Many of the investigations will need to assemble quite a bit of data before they can even begin to interpret it.

Not all of the mission science is being done by Juno itself. Other spacecraft, like Hubble, are making observations in support of the Juno mission. Today, Hubble released a gorgeous video of Jupiter's aurora, something that Juno will be able to investigate once it's in orbit. Unlike Hubble, Juno will be able to see an entire pole at once (instead of just the half that's facing Earth).

Now that science is beginning, a lot of people are asking questions about how this mission will be different from Galileo. To be sure, Juno and Galileo share a lot of similar instruments -- plasma waves, magnetometer, energetic particles, radio science. All of these instruments are designed to investigate Jupiter's magnetic field, energetic particle environment, and internal structure. What makes them different?

It's mostly about location. "Fields and particles" instruments do in-situ investigations, meaning that they measure properties of Jupiter at the location of the spacecraft. This is in contrast to remote sensing investigations, which measure properties of Jupiter from a distance.

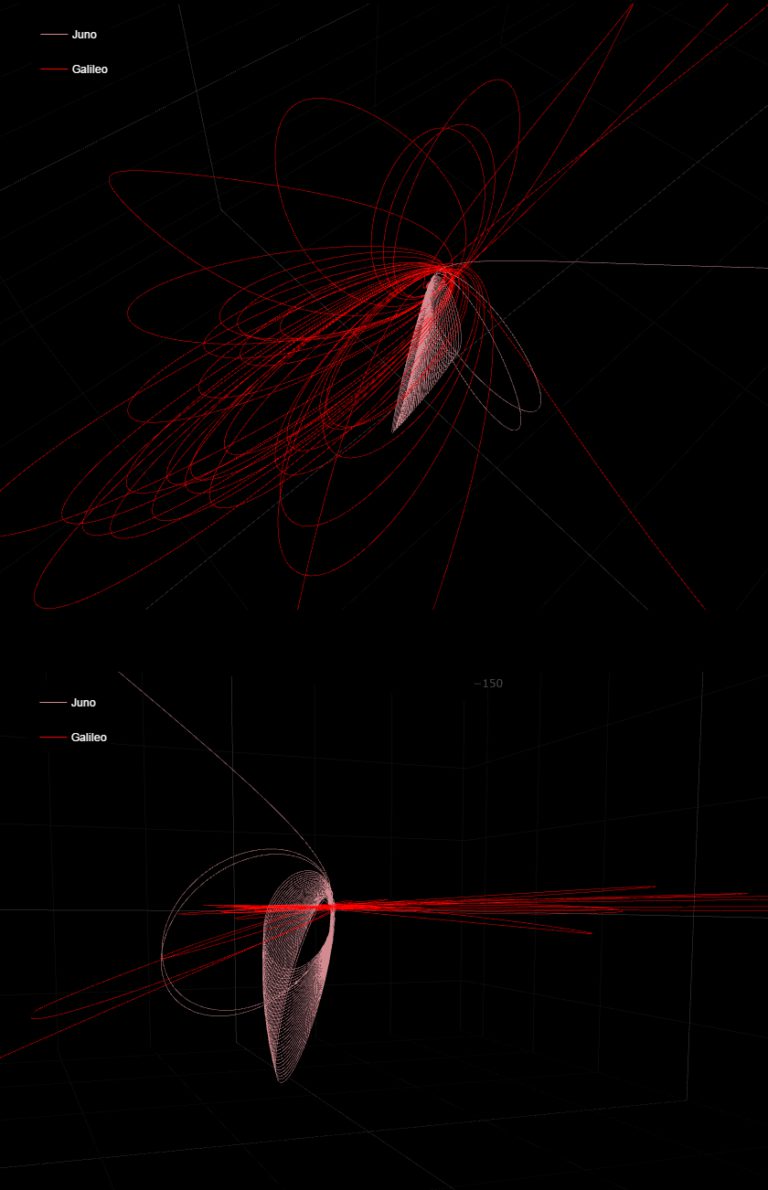

If you are an in-situ investigation examining a 3-dimensional structure like Jupiter's magnetosphere, you need to take your spacecraft to as many different locations within the 3-D structure as you can. Because it focused on Jupiter's moons, Galileo was constrained to an orbit close to the plane of the moons' orbits, confining it to only a 2-D slice of the magnetosphere around the equator. Galileo also avoided Jupiter's donut-shaped radiation belts, mostly staying relatively far away from Jupiter outside Europa's orbit, so hardly probed the magnetosphere close to the planet.

In contrast to Galileo, Juno has a polar orbit that will fly to a wide variety of different latitudes and distances from Jupiter. And its orbit takes it through the donut hole of the radiation belts, very close to the planet.

Here are two views comparing the Galileo and Juno orbital trajectories at Jupiter, created using a really terrific visualization tool built by Science News. You can see that while Galileo samples a lot of longitudes, all its orbits are in one plane and mostly pretty far from Jupiter.

Together, these two characteristics of Juno's orbit -- its high inclination, and the close approach of its periapsis -- will make its measurements of Jupiter's magnetosphere much more complete than anything Galileo could achieve. On the other hand, Galileo sampled a wider variety of longitudes at great distance from Jupiter. The two data sets complement each other. In the long term, I'm sure that the science team will be incorporating Galileo data into their work on interpreting Juno results.

Here's another Science News visualization -- it has to zoom way in at the end to show you how much closer Juno gets to Jupiter than any other mission ever has.

Jupiter's visitors Every spacecraft that has visited Jupiter has traced a different path past or around the giant planet. Here's 43 years of Jupiter drive-bys, compressed to a couple of minutes. Learn more here. (Story by Chris Crockett; animation by Sean Kelley; production by Helen Thompson.)Video: Science News

It's terrific that the science is beginning, even before Juno gets into orbit. Tomorrow I'll put a post together with suggestions on how to follow orbit insertion events. Stay tuned.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth