Judy Schmidt • Jun 24, 2016

WISE Views in Infrared

I enjoy image processing but was on hiatus for a few months after getting tired of digging through Hubble's archive. I know there's still more to find in there, but sometimes I feel like I'm going in circles. More than once have I been looking at some data and only to realize I've already worked on this or that.

Then, about two months ago, William Keel posted a GALEX image of NGC 6872 in an APOD discussion thread for the same galaxy. I decided to go poking around in the MAST Data Discovery Portal and check out the FITS files. Eyeing some fresh astro images rekindled the old flame. One thing led to another, and before I knew it, I was creating a big Andromeda mosaic out of GALEX data; the Helix Nebula came next.

From there, I ended up in Spitzer's archive, which is yet another observatory I've been meaning to check into. I processed Spitzer's Helix and then found the Pleiades and did them, too. Spitzer's archive was full of tremendously beautiful imagery, but not for the entire sky. The Pleiades mosaic doesn't extend far beyond the stars themselves. I was curious!

Enter WISE. By now, after working with Spitzer, I've convinced myself these infrared datasets haven't received nearly as much attention as they deserve outside the astronomical community, and I think I might know why. A lot of people do not like infrared astronomy. It takes extra effort to interpret an image that has an unfamiliar color palette, and if you don't like the way it's presented, you might have little motivation to put forth any such effort.

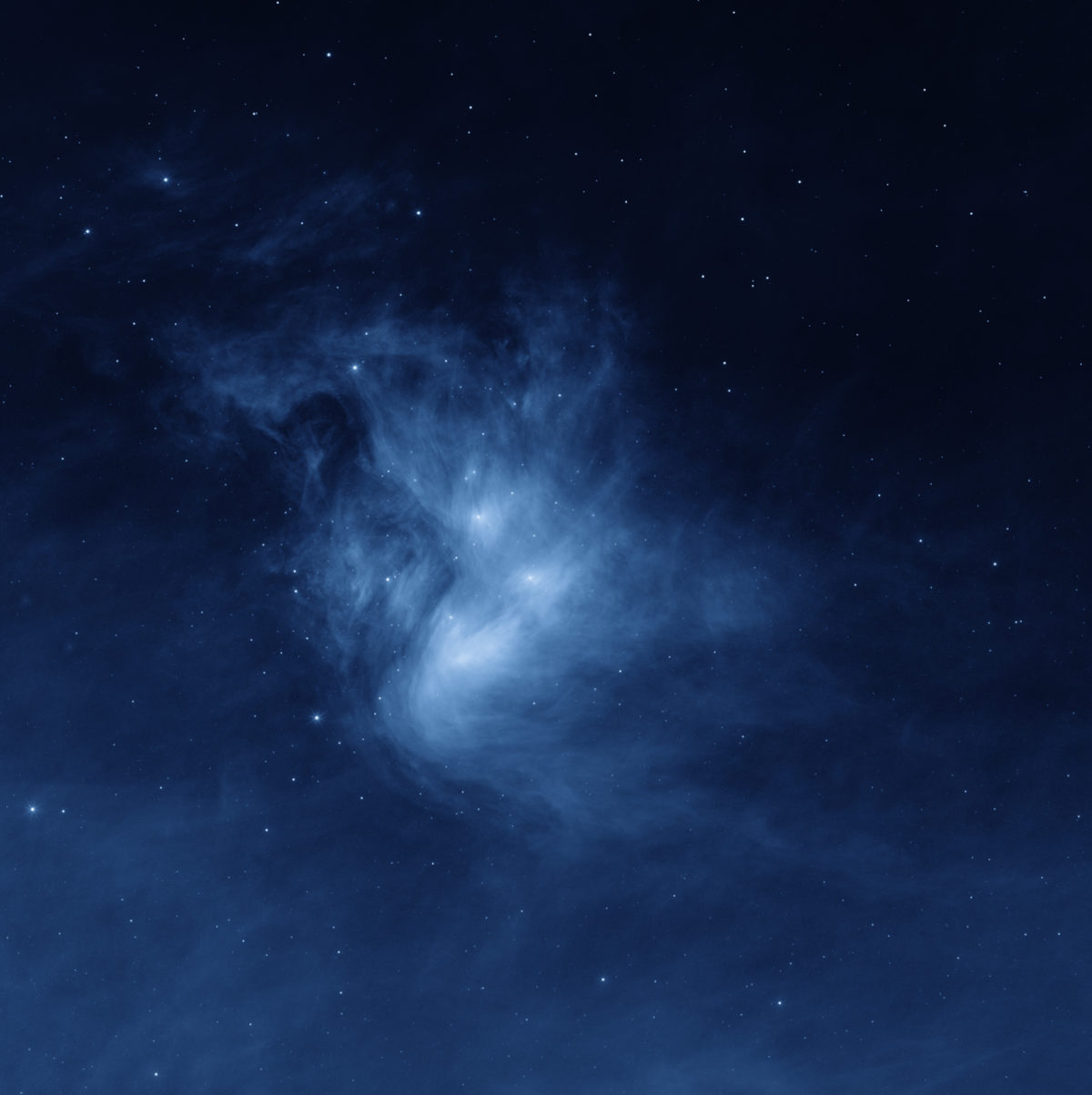

I decided to process the WISE Pleiades mosaic and try out some color palettes to see if I could satisfy my own personal aesthetic and then test it on my followers. They seemed to love it, so that's a good sign. If the fact that it was infrared bothered anyone, they didn't speak up.

Here are the lovely Pleiades and their associated filaments and clumps of dust. To their south is a diffuse warm glow known as the zodiacal light. I am very impressed by how bright it is in this picture and the dynamic range with which it presents. In visible light, it's often barely discernible if you can even find skies dark enough to view it. It's bright enough in infrared to pose a bit of a nuisance to astronomers, but in this case I think it is wonderful.

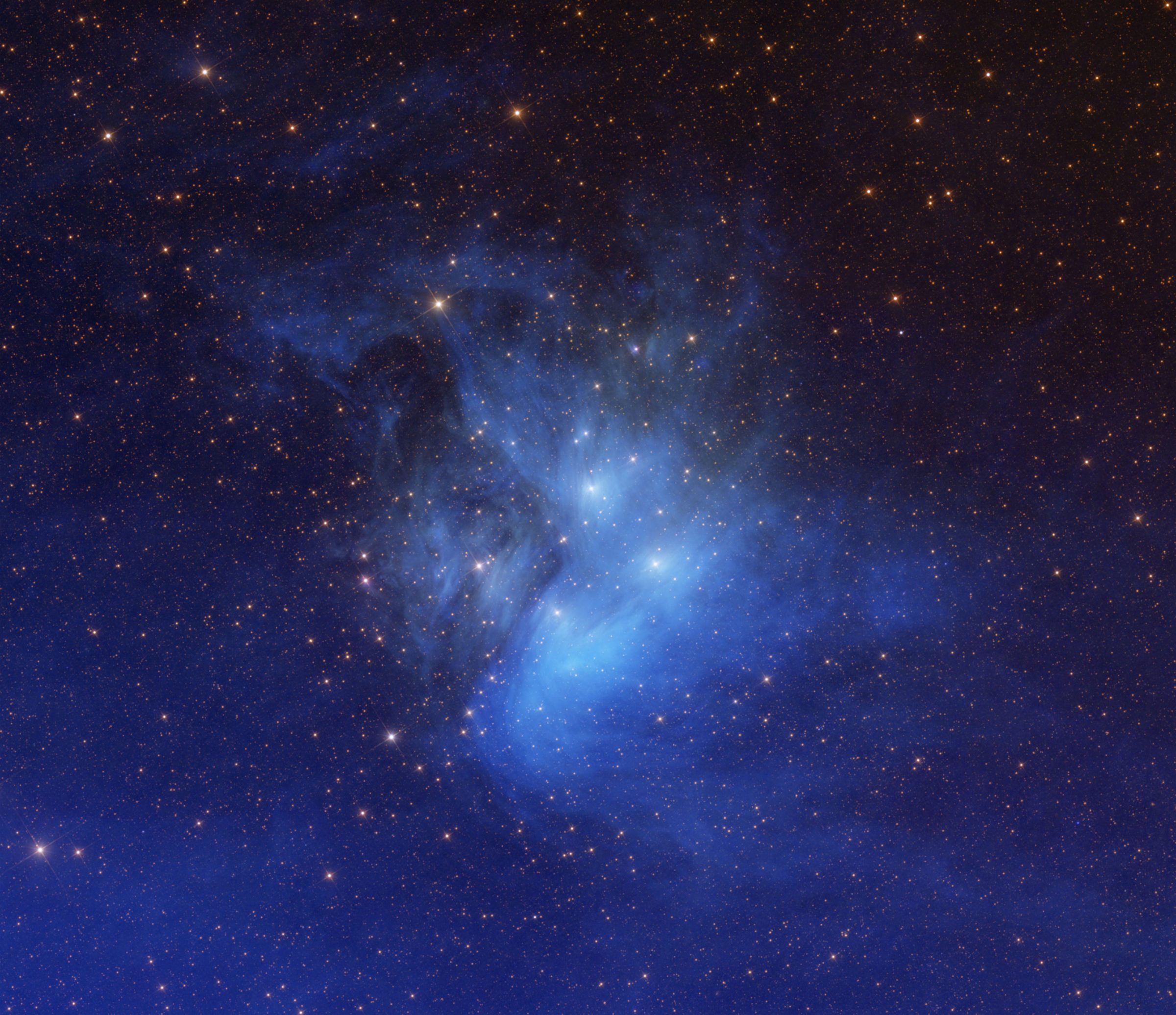

The Pleiades never disappoint, do they? I think I am in love with infrared. In visible light, the Pleiades illuminate dust to create a reflection nebula. They can look isolated. To WISE's infrared vision, the Pleiades are far from isolated; look at that long tail.

(It is possible to capture more of the dust in visible light than the DSS overlay shows and it has been done a number of times by some very talented astrophotographers. The DSS image is just a typical example.)

If you are familiar with WISE, you know it's an infrared observatory, and this image may not look anything like what you might expect from it. WISE image releases typically look like this. While useful, they're not particularly pretty, and they might have even turned off a lot of people from infrared imagery. I've definitely seen a general lack of interest in infrared imagery and have even seen more than a few people express displeasure about JWST being an infrared telescope, fearing all the images will be...well, ugly.

Worry not, fellow humans! JWST will produce beautiful images and they need not be presented in weirdo colors. This particular image has only one special processing trick beyond what I normally do. After some careful consideration I decided to reverse the wavelength order. I nearly always put the shortest wavelength in the blue channel and the longest in the red. This time, I did the opposite. I was afraid that cognitive bias would prevent people from enjoying this image if it was a fiery red, given the extreme familiarity the astronomy community has with the Pleiades. Sometimes you've got to do something unconventional to get the result you want.

This is what the infrared Pleiades look like with a normal wavelength arrangement. I wasn't going to post it, but after asking around I found out people split evenly on their preference of the red versus the blue version.

Processing notes: Thankfully, most of the processing work was aligning and matching up each of the frames to one another. This is fairly tedious work, but it's not nearly as bad as dealing with cosmic rays. There were a few annuluses to deal with near some of the brighter stars, but they only took about 15 minutes to be rid of. I did not saturate the colors or apply any sort of sharpening.

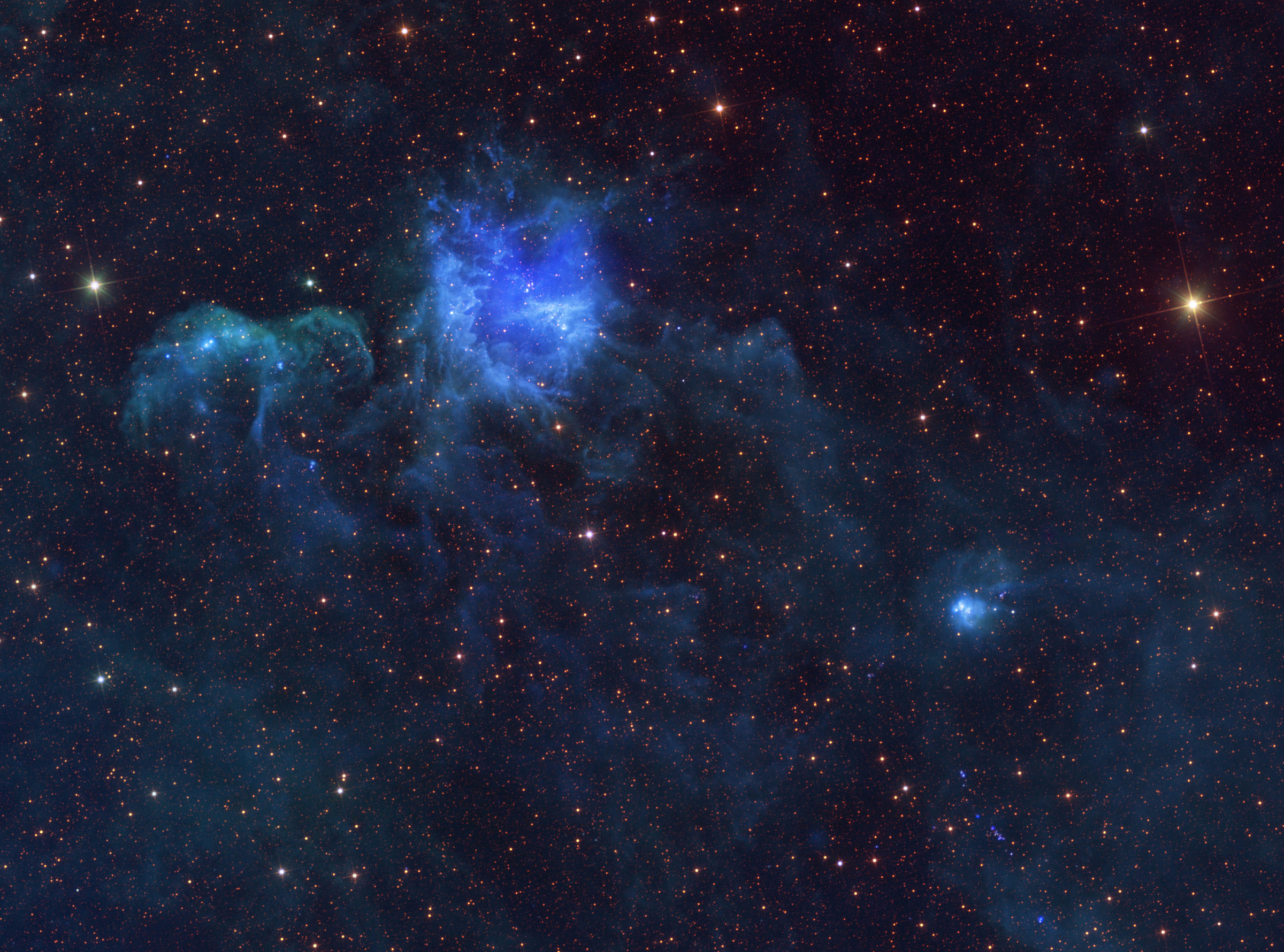

Here is another infrared color image from WISE. Once again, I've reversed the wavelength order for what I consider a more aesthetically pleasing result, so keep in mind that deep blue is the longer wavelength and red is the shorter wavelength. The Pacman Nebula, otherwise known as NGC 281, is revealed not as a singular pool of light but as a larger structure of seemingly related knots and trails of dust. Pacman itself is the largest blue structure northeast of center. The two other noticeable structures do not have any special designations. In the lower right corner of the image is a blueish strand of stars I included because it seemed interesting. Deep blue in this case corresponds to the warm dust in the 22 micron channel. In visible light, a knot of dark, obscuring dust is visible in the location of the strand, but no stars are.

I tried very hard to balance the colors this time and not have the blue and red overwhelm the image, so more cyan is showing through this time, unlike with the Pleiades image. Nine WISE frames were aligned and matched to create a smooth mosaic. Some small optical artifacts were removed. No sharpening or color saturation was done.

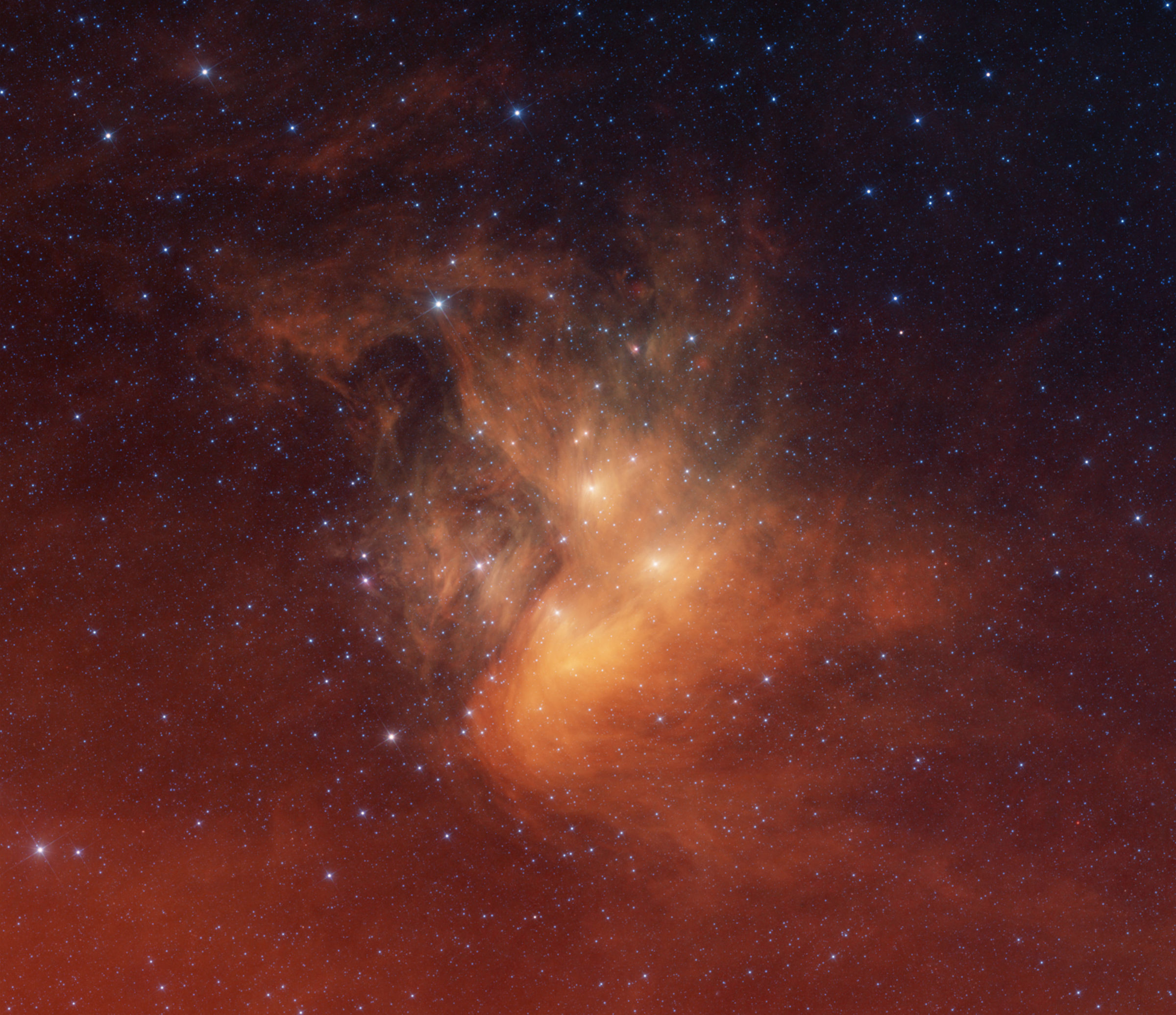

I am still pondering the aesthetics of the WISE data. Here is another infrared image. Lambda Cephei—demure and largely ignored in visible light—stands out with its bright red shock wave to WISE's infrared eyes. Jim Kaler, as usual, has a nice way of describing the star if you would like to know more about it.

For the processing on this one, I separated the four WISE channels into two distinct groups, treating each group as if it was a two-channel, pseudogreen image. The dust group (W3 & W4) is given preference for visibility while the star group (W1 &W2) is only faintly applied on top of the dust group as an additive layer. I also learned about some new artifacts in WISE imagery called latents which are leftover spots on the detector where bright sources were previously imaged, so I got rid of those along with the usual annuluses, otherwise known as filter ghosts.

So far I've learned that perhaps no single palette works best in all cases, though there might be one that works well in most. The Pleiades are compelling in blue because people expect them to be blue. For a lot of other cases, that may be dead wrong. I've also learned that I do not have to achieve maximum color separation to create an informative image. It might even be much more confusing if the colors are wildly varying. As long as it's enough to point out what's important, that's good enough.

Ultimately, I hope more people learn to appreciate infrared (and other non-visible wavelengths!) in the future. I also hope that more people will be inspired to look into these underappreciated archives with me.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth