Scott Maxwell • Jun 04, 2015

Using Cardboard to Tour Mars

I went to Mars last week. That’s not a particularly new thing for me, of course. I just don’t normally get to take so many other people along.

Maybe I should explain.

From 2004 through 2013, I drove Mars rovers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory; for most of that time, I was the solar system’s only Mars Rover Driver Team Lead. I was one of the original eight rover drivers on the Mars Exploration Rover (MER) mission, driving first Spirit and then her twin sister, Opportunity. Indeed, I’ve driven three of the four rovers that have ever landed on the red planet: Spirit, Opportunity, and Curiosity, only Sojourner excepted.

To say I was enthusiastic about it would be an epic understatement. I adored everything about doing that work, just as I adored the team I did it with. And why wouldn’t I? I was that kid who grew up immersed in science fiction, and suddenly my day job was to reach out my hand across millions of kilometers of empty space and move something on the surface of another world.

But as rewarding as that job was, the best part was getting to take everyone on Earth along with me — anyone can be a backseat rover driver, so to speak. Thanks to the foresight and tenacity of MER’s Principal Investigator, Steve Squyres, MER put every single picture that came back from the rovers up on the Web within hours, free for the entire world to see. When it landed, Curiosity followed suit. If you live in the right time zone or are just an early riser, you might see the latest pictures from Mars even before the mission team does. A community grew up around those pictures, and I used hundreds of them in the many dozens of outreach talks I did over the years.

Oh, right: the outreach talks. I typically craft a new one for each audience, but they all have this in common: they’re almost entirely pictures of the rovers or from the rovers — I hate putting text on slides — and me, talking. I think I do well within the limits of the technology, but I never feel quite like I can tell the story properly. In particular, I can’t show panoramas, those gorgeous vistas the rovers have visited, and without the panoramas, it’s hard to get a sense of the sheer scale of these missions; looking at only a single image is like seeing the Grand Canyon through a straw. No matter how eloquent I am, without the panoramas, it’s hard to really transport the audience to Mars. A panorama would be worth ten thousand words.

Enter Cardboard, Google’s virtual reality viewer. Last year, Google — my current employer — introduced a fold-up piece of cardboard (seriously: you can make your own from a pizza box) that wraps around your phone. Hold it up to your face while your phone runs the appropriate software (for instance, the demo for Android or iOS), and you see a 3-D world around you. Have you taken a panorama with your phone, maybe on vacation? Cardboard lets you stand in the middle of that panorama and look around it, to revisit that vacation spot while you’re in your living room — or give it to a guest, so they can see what you saw.

So you can see where this is going.

This year, Google doubled down on Cardboard by introducing Expeditions, a way for teachers to take their classrooms on field trips to anywhere. You can think of Expeditions as the Google Magic Schoolbus. By giving a simple tablet interface to a teacher and Cardboard viewers to the students, the teacher can lead the class on a virtual reality field trip — to the Great Wall of China, or to the American Museum of Natural History, or under the sea to learn about coral reefs.

Or to Mars.

And that’s where these two threads of the story meet. Last week, I flew up to Google I/O to help demo Expeditions for the conference attendees. The hard work had already been done by The Planetary Society’s own inimitable Emily Lakdawalla, who had put together a great series of rover panoramas documenting the life of Spirit. And since Spirit was the best Mars rover ever, it was easy for me to play my part.

A dozen or so at a time, group after group of conference attendees eagerly picked up a Cardboard viewer and donned headsets that enabled them to hear me over the din. And I led them through Spirit’s life, as seen through her own eyes.

We stood together on Spirit’s lander, newly arrived on Mars, discovering the cruel joke that that planet had played on her — filling up Gusev Crater, her ancient lake destination, with lava, thus forever burying the water evidence she’d come 500 million kilometers for. (The tablet interface let me point out particular rocks that were obviously lava rocks instead of the expected sedimentary rocks; the students see an arrow pointing to the feature of interest and can turn their heads until they see the thing I’m talking about. They saw it just as Spirit had seen it.)

Turning, we spotted hope on the horizon: the Columbia Hills. Had they maybe been altered by water before lava covered the crater floor? There was only one way to find out: Spirit would have to go there. Those hills were impossibly far away for Spirit to reach, of course — but Spirit never let a little thing like impossibility stop her. So off she went, taking us with her.

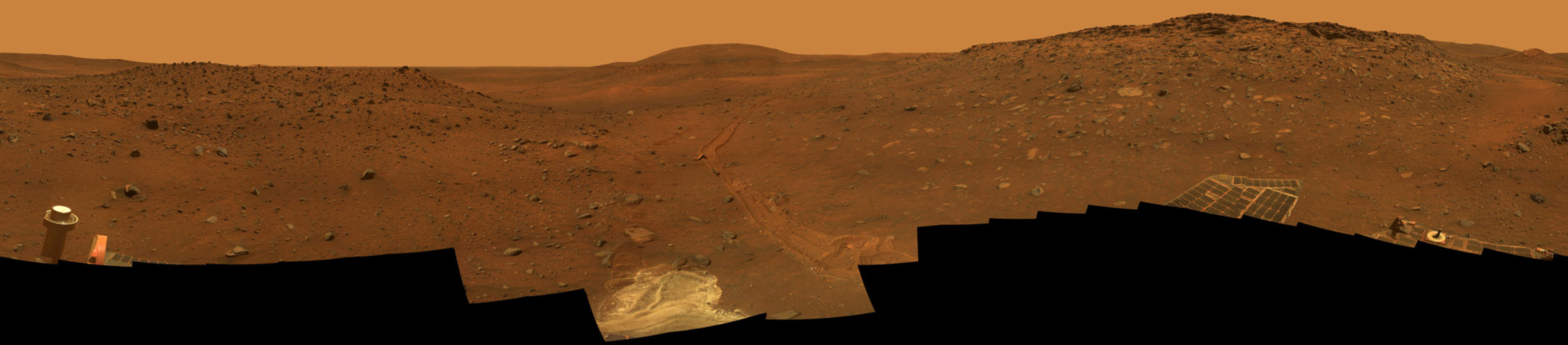

We caught our breath together at a waypoint on the long road to the hills. We looked back at our own tracks, at the dangerous rocks we’d dodged — and ahead at the still-distant Columbia range. At our target within that range, Husband Hill.

We viewed the world then from partway up the “on-ramp” to Husband Hill, West Spur. Spirit had already traveled impossibly far at this point — and we saw some evidence of the price she’d already paid: we looked back at the mess we’d made of Engineering Flats, where we’d had to stop to diagnose an increasingly troublesome wheel. And we looked ahead, at Husband Hill, the hill we were climbing — and we wondered how our little golf-cart-sized rover, who wasn’t made to climb anything bigger than a watermelon, was ever going to make it up a hill the height of the Statue of Liberty. Impossible.

And then we saw the world from the top of Husband Hill. We felt that pride, sensed that accomplishment, as Spirit had once again beaten the odds. We saw our own tracks leading to the summit, that gleeful last sprint as we scrambled to the very top. We scanned the horizon, saw dust devils screaming at 80 km/h across the floor of Gusev Crater.

And — just as Spirit herself did when she was good and ready — we made our way down the far side of that hill and kept on going. We were there where the troublesome wheel gave out at last, just in time to temporarily trap Spirit in the soft-sand region named “Tyrone.” We saw the evidence of her struggle to escape Tyrone — successful, thank goodness — and we saw the tracks that led to Spirit’s winter haven that year. We saw the bright silica turned up by the trench the broken wheel dug as we dragged it along, silica that proved to be our best water evidence to date.

And we saw, finally, the last sight Spirit ever saw: the foul sand trap named “Troy” that, in the end, she was unable to escape. Just there, her destination, Von Braun hill, beckoned — so close, so close — as Spirit struggled for freedom and gasped for sunlight and then, heartbreakingly, closed the eyes that had seen so much.

It will be hard to go back to outreach talks that use plain old images after that field trip to Mars.

Together, we learned the lesson Spirit spent her life teaching. Mars was impossibly far away — but she went there. The Columbia Hills were impossibly far away — but she reached them. Husband Hill was impossibly tall for our little rover — but she climbed it. So what’s the lesson? Find a thing that’s worth doing, and do it, even if it seems impossible. Because you might find that the thing that looks impossible, isn’t impossible after all. You find that out only if you try.

Thank you, Spirit. It was wonderful to see your world through your eyes once more. And to be able, in a whole new way, to take others on that journey too.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth