A.J.S. Rayl • Jul 04, 2013

Mars Exploration Rovers Mission Update: Opportunity Continues Sprint to Solander Point

Sols 3325 - 3354

Mars Exploration Rover

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Maas Digital

The Mars Exploration Rover (MER) mission celebrated its 10th anniversary of leaving Earth in June, as Opportunity continued the sprint to its next winter haven at Endeavour Crater.

It was June 10, 2003 that Spirit, MER-A, Opportunity's alpha twin, lifted off from Cape Canaveral to leave Earth forever and become a Mars explorer. But that date is only the first of a number of MER anniversaries coming up that NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) will be acknowledging.

Opportunity's launch anniversary is coming up July 7th. Then, there were the unforgettable, breathtaking landings - Spirit on January 3, 2004, Opportunity on January 24, 2004 Pacific Standard Time, to be celebrated in January 2014, in a big way. The Planetary Society will be hosting events in cities across the country and around the world, as well as holding a celebration in coordination with NASA.

Although Spirit failed to emerge from a winter hibernation, and effectively ceased communication in March 2010, the rover worked for 7 years in some of the toughest terrains on Mars, all but redefining the word 'perseverance' and setting a standard and robotic work ethic for all future rovers to follow. On the other side of the planet from where Spirit now sits as a silent monument to exploration, Opportunity roves on. In recent months, the veteran robot field geologist has been making some of the most important discoveries on the entire mission.

Like the month before, June 2013 was pretty much all about driving, and Opportunity seemed to be in fine form, roving on 13 of the month's 30 sols, heading south along Endeavour Crater's western rim. "We are now into our sixth Mars year, and we're driving as fast as we can," Steve Squyres, MER principal investigator, of Cornell University, told the MER Update. "We can't wait to get to Solander Point."

Spirit blast off from Earth

On June 10, 2003, Spirit, compactly stowed in a tetrahedron-shaped landing platform, took off from Cape Canaveral above a Boeing Delta II rocket, and began its journey to Mars. It was that moment, perhaps more than expected, that deeply touched MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres. "I spent so many years working with this team to create these rovers," he told the MER Update author years ago. "I stood next to them, crawled underneath, and held pieces of them in my hand. I had invested so much of my hopes and dreams, and so had everybody else on the team. Then we put them on a rocket to blast off. The day Spirit launched, I suddenly realized that it had left Earth forever, that I was never going to see this rover again. I treasure those moments I had with Spirit before we launched and I miss them. That may sound goofy, but that's how I feel."NASA / Maas Digital / Ecliptic Enterprises Corporation / Boeing

Opportunity left Matijevic Hill and Cape York in mid-May, after sending home the most compelling evidence for near neutral flowing water found on the mission to date. During the last four weeks, the rover has been making tracks on its 2.2-kilometer (about 1.37 mile) journey to Solander Point, where it will spend its sixth Martian winter. "We're doing as close to pedal to the metal as possible," confirmed Bill Nelson, chief of MER engineering team, at JPL. By the end of June, Opportunity was about halfway there.

Cape York and Solander Point are sections of the broken rim of the ancient, 22-kilometer (13.67-mile) Endeavour Crater, which contain rocks and remains of the Noachian Period some 4 billion years ago, when Mars was a lot more like Earth. "We're heading to a 15-degree north-facing slope with a goal of getting there well before winter," said John Callas, MER project manager at JPL.

Solander Point is actually at the northern tip of Cape Tribulation, where orbital data indicates there is a motherlode of clay minerals waiting to be discovered. Currently, the rover is "on track" to reach Solander Point by August 1st, noted Ray Arvidson, deputy principal investigator, of Washington University St. Louis (WUSTL).

On the first day of June, Opportunity pulled up to Sutherland Point, a small, peninsula-like chunk of Endeavour's rim situated between Cape York and Solander Point. From there, the rover cruised along the Endeavour side of this rim section, and then onto the flat, apron area that divides Sutherland Point from Nobby's Head, just to the south.

The robot field geologist continued her trek, roving to the northern end of Nobby's Head, another section of big crater's broken rim that features some north-facing slopes. From there, Opportunity drove around its western flank, or far side. "We took the scenic route around Nobby's Head rather than taking the fastest route," said Squyres.

The engineering team wanted to take some stereo pictures "to validate that there are slopes of 10-to-15 degrees that would be good bail-out slopes if we had to turn around and spend the winter there," said Arvidson. While fallback plans and options are a matter of course for this mission, no one's planning on turning back.

Making fast tracks and two to three sols ahead of schedule, Opportunity was commanded to take a slight detour to check out the southern interior of Nobby's Head. Bright deposits seen in HiRISE images from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) indicate there may be flat, light-toned rocks at Nobby's Head that are like the Whitewater Lake outcrops on Matijevic Hill. [As reported in previous MER Updates, the Whitewater Lake rock unit is the oldest rock unit the rover has ever seen, and the one that holds the evidence for clay minerals found on Matijevic Hill.]

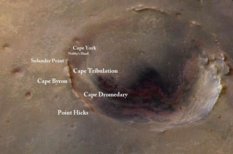

Overview of Opportunity's trekking grounds

This image, taken by the University of Arizona's HiRise camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows the sites where Opportunity has been and is going. It was colorized and labeled by Stuart Atkinson, MER poet, author, member of UnmannedSpaceFlight.com, and frequently contributor to the MER Update. Atkinson has been following Opportunity's path to Endeavour in a blog called The Road to Endeavour, which you can visit here.NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / S. Atkinson

When Opportunity arrived at the appointed destination at Nobby's Head however, there was no outcrop target within reach of its instrument deployment device (IDD) or robotic arm, and the team "decided to punt," said Callas. "We want to get to Solander by August 1st. We are on track, but we have to be careful. If we have some anomaly or complexity with the vehicle, we could lose drive opportunities."

The team previously established some pretty hard and fast rules on the acceptable margins for driving to Solander, and they followed them. "Rather than eat into our margin to a degree that might not have been safe, we followed the rules that we set for ourselves," added Squyres.

The venture into the interior of Nobby's Head wasn't wasted. Opportunity took some pictures of the rock and ledges and layers with its panoramic camera (Pancam) before hitting the road. "Sutherland Point and Nobby's Head look like smaller versions of Cape York, which is not unexpected," noted Arvidson. "They are little, bitty tips of the dissected rim of Endeavour Crater."

From Nobby's Head, Opportunity began "a beeline" across Botany Baym according to JPL's Ashley Stroupe, one of MER's rover planners. "We are now less than a kilometer away from the northern slopes of Solander where we want to spend the winter," she reported as June was coming to an end.

The MER team is enthused and excited, even a little anxious to get to Solander Point as soon as possible. For starters, this section of Endeavour's rim offers Opportunity access to a much taller stack of geological layering than Cape York the area, where the rover had been working since arriving at Endeavour Crater on August 9, 2011. In other words, Solander Point is a bigger hill. While Cape York exposes a few meters of vertical cross-section through geological layering, Solander Point by comparison exposes about 10 times as much, said Arvidson. "Getting to Solander Point will be like walking up to a road cut where you see a cross section of the rock layers. But we'd like to get there early enough to have time to do some science around the base," he said.

Meanwhile, down on Earth, the MER team held a press conference on June 7th to update members of the working press and media on Opportunity's travels and findings at Cape York. During the telecon, Callas, Squyres, and Arvidson reviewed the rover's status and coming anniversaries; its eight-month study of rock units and other geological formations on Matijevic Hill during which it found a combination of elements that point to clay minerals; and the plans for a winter science campaign at Solander Point, all of which have been covered in detail in MER Updates during the past year.

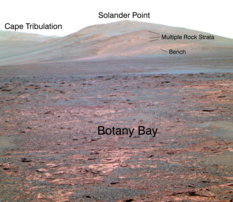

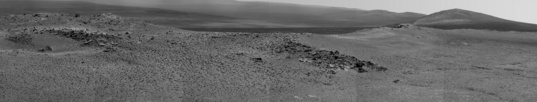

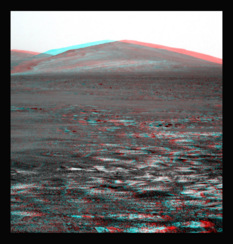

View of Solander Point

From her arrival location at Sutherland Point, Opportunity used her panoramic camera (Pancam) to acquire this view of Solander Point during her Sol 3325 (June 1, 2013). Plans are for the robot field geologist to spend her sixth Martian winter at Solander. Botany Bay in the foreground, is a topographic saddle exposing sedimentary rocks that are part of the Burns formation, a geological unit this rover examined in years past. At Botany Bay, the Burns formation is exposed between isolated remnants of Endeavour Crater's rim. Solander Point is actually at the northern most tip of Cape Tribulation, and both are sections of Endeavour's broken rim south of Botany Bay. Orital data indicate a motherlode of clay minerals at Cape Tribulation and it is where Opportunity will head once the Martian winter passes, sometime in the first half of 2014.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

Back on Mars, Opportunity quietly chalked up its fifth Martian year on June 21, 2013. One Mars year is 686.98 Earth days or 1.88 Earth years, roughly equivalent to two Earth years. In a little more than six months, the veteran rover - and her team on Earth - will celebrate their 10th Earth year anniversary of roving and exploring the Red Planet.

Three Martian days later, on the rover's Sol 3348 (June 24, 2013), Opportunity pushed past the 37-kilometer mark. "That drive not only broke 37 kilometers, it also broke 23 miles," reported Nelson.

Just a few weeks ago, it would have been cause for major celebration, as reported in previous MER Updates, because that milestone would have meant that Opportunity beat the all-time, Earth rover distance record on another planetary body. The former Soviet Union's robotic Moon rover, Lunokhod 2, which explored the Moon's Le Monnier Crater for about five months in 1973, has since held the record with a published 37 kilometers (23 miles). New news about just how far Lunokhod 2 actually drove however emerged in June.

For some 40 years, Lunokhod 2's record had been recorded as 37 kilometers. But time marches on and technology gets better. In 2010, the Soviet Moon rover was located in images taken by the narrow angle cameras onboard the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, the NASA spacecraft that has been studying the Moon since 2009. [See: the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera website's "Lunokhod 2 Revisited" feature] And in those images, the tracks made by Lunokhod 2 can be seen.

Lunokhod, by the way, is the English translation of the Russian word "луна Уолкер" which means Moon Walker.

For Squyres, that 37 kilometers always seemed "too round of a number." So, he began a quiet investigation, reaching out to the Russians through Phil Stooke, associate professor at University of Western Ontario, and author of The International Atlas of Lunar Exploration and The International Atlas of Mars Exploration. At the same time, Squyres asked MER science team member and geologist Brad Jolliff, of WUSTL, who is also a member of the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera (LROC) team, to look into the Lunokhod 2 traverse distance using the latest imagery of the Moon.

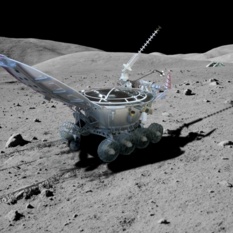

Lunokhod 2 on the Moon

This simulated image shows Lunokhod 2 as it might have roved on the Moon. The second of two unmanned Soviet rovers sent to the Moon in 1973, Lunokhod 2 holds the international record for distance traveled on another planetary body. For decades, it was stated that this "Moon Walker" traveled 37 kilometers (23 miles) on the surface of Earth's Moon. But in June 2013, new news revealed that the robotic rover actually traversed some 42 kilometers. It is the only rover distance record that Mars Exploration Rovers Opportunity has to best.Russian Academy of Sciences

"I decided that before we made any claim about having exceeded the Lunokhod 2 record, we damn well better find out exactly what they really did," said Squyres. "I wanted to make absolutely certain that we really knew what the true Lunokhod accomplishment was."

Turns out, Russian planetary mapper, Irina Karachevtseva, and her colleagues at the Moscow State University of Geodesy and Cartography (MIIGAiK) had revised the calculations of Lunokhod 2's mileage using the same images taken by LROC. The new distance, Karachevtseva wrote in an email, was approximately 42.1 kilometers, basically the distance of a marathon. Although the Russian scientists reported their findings at various planetary-science conferences during the past year, the news of the revised Lunokhod 2 distance only hit the American press this month as Opportunity was thought to be closing in on the record.

"How do you go from 37 to 42? - that's a big increase, so I and others thought let's just give that a double check, do our due diligence," said Jolliff, who as a member of the LROC team has worked with the Moon images a lot.

Jolliff enlisted grad student Ryan Clegg and began "a little project" at WUSTL. The tracks are "remarkably well preserved" and can be readily seen in the images, Jolliff said. "But it's not easy to see everywhere it went."

Even so, they found one traverse where Lunokhod 2 doubled back on its traverse, and then did the traverse again, in effect making a triple segment," Jolliff explained. By all MER accounts, since MER has doubled back on occasion, that counts. "That triple segment was 2 kilometers long, so it added 4 kilometers, and got us over 40," he said.

LROC images show where Lunokhod 2 traversed back and forth across small craters in a star-like pattern, and on a few other drives went out and then roved back along same exact path for magnetometer experiments. Jolliff and Clegg also noticed circles where the rover would turn in place to do a panorama, "at least 36, but maybe as many as 80 or more," noted Jolliff. "If you add a little bit of odometry for each of those, pretty soon you are pushing 41.5 getting close to 42 kilometers, so, in fact, we have been able to verify that long distance, not right down to the meter, but certainly approaching Irina Karachevtseva's estimate," he told the MER Update.

Just to be sure, Jolliff put another grad student, Mike Zanetti, on the case. Using a different approach, he came up with 41.8 kilometers.

"Everybody agrees now that it was at least 40 kilometers," said Squyres. "But we're still working out exactly what the numbers are, both in the United States and in Russia."

Once the Americans have their best estimate, they plan to communicate their results to a colleague in Russia, Alexander T. (Sasha) Basilevsky, director of the Laboratory for Comparative Planetology, Vernadsky Institute, at the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow. A well-known lunar scientist, Basilevsky was involved with the Luna 21 / Lunokhod 2 mission. [Luna 1 delivered Lunokhod 2 to the surface.]

Lunokhod 2 model

A Moon rover controlled remotely by a team of Soviet controllers on Earth, Lunokhod 2 is about 170 cm (5' 7") long x 160 cm (5’ 3”) wide x 135 cm (4’ 5”) tall, and appears almost circular when viewed from above, according to a post at the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera (LROC) website, by LROC Principal Investigator Mark Robinson, of Arizona State University (ASU). The vehicle had eight wheels and could travel at either 1 kilometer per mile or 2 kilometers per mile (0.6 and 1.2 mph). For more images and findings about Lunokhod 2's actual traverse distance please visit Arizona State University's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera (LROC) websiteHayk/WikiCommons

"Lunokhod 2, which looked sort of like a fancy, futuristic washing machine on wheels, had both a solar electric source and a nuclear source," Jolliff pointed out. "It had this lid that was closed at night, when the nuclear heat source kept it warm through the cold lunar nights. During the day, the lid would be opened, exposing the solar panels so they could charge up, and off it would go. And it was done by teleoperation," he noted. "It really was pretty spiffy."

The way Squyres sees it, if and when Opportunity drives beyond 42 kilometers, MER's claim to the title will be about more than breaking a record. "Personally, the main reason I want to make a big deal about passing the Lunokhod record, when and if we do, is to call attention to the Lunokhod 2 accomplishment, to highlight the historical significance of what the Soviets managed to achieve on the Moon by the fact that we didn't manage to exceed that for 40 years," he explained. "Okay, it was the Moon and not Mars, and it's different. Still, when you consider the fact they were able to do what they did with 1973 technology, it was a truly magnificent accomplishment. If one of the things that we can do with this little drama is to shine a spotlight on what the Russians did accomplish in those days, I think that's a good thing," he said.

"Because of what we [on the MER team] do for a living, we have an enormous amount of respect for what the Soviets accomplished," Squyres added. "But a lot of people haven't even heard of Lunokhod and they should. Frankly, some of the Russian robotic accomplishments on the Moon, because they took place in the shadow of Apollo never received, in my opinion, the recognition they should have received. And now, it turns out the Lunokhod accomplishment was even greater than we had realized," he said.

"Our goal is to explore Mars," Squyres reminded. "If we break the record in the process, so be it. At this point however, we're going to get to Solander Point pretty quick and our odometry is only going to be somewhere between 38 and 39 kilometers, and then we're going to slam on the brakes and start doing science again. We're not going to be wracking up the miles like we have been."

So, Opportunity has kilometers to go before she can sleep with the honor of being the most traveled rover on another planetary body. For now, Lunokhod 2's record is safe, at least until the Martian winter comes and goes in the southern hemisphere of the planet, and Opportunity sets out for Cape Tribulation and parts beyond.

Learning that Opportunity would not be claiming the title in June was something of a let down for the rover's drivers. "It was a little disappointing to find out that what they had been publishing all this time wasn't accurate," said Stroupe. "We would have loved to have beaten the distance record this summer, but that's okay. We want to beat the real number, and we're still absolutely confident that we will. It's just a matter of time."

The team's focus in the meantime has shifted back to Solander. The hope is that Opportunity will find more evidence for flowing water there and better-defined layers in the rock to discern different stages in the history of ancient Martian environments. So far, things are "looking good," said Arvidson. "As we get closer, the bright layers that we've been seeing are getting increasingly detailed in the pictures the rover has been shooting."

In addition to tantalizing rock layers, Solander Point also offers plenty of north-facing slopes that will enable the solar-powered to angle its arrays toward the Sun throughout the coming Martian southern-hemisphere winter. This actually is why this segment of Endeavour's broken rim was chosen to serve as the rover's haven for its sixth Martian winter.

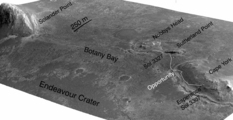

The path to Solander Point

A stereo pair of images from taken from Mars orbit but the University of Arizona's High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera were used to generate a digital elevation model that is the basis for this simulated perspective view of Cape York, Botany Bay, and Solander Point on the western rim of Endeavour Crater. The view is from the crater interior looking toward the southwest, and the vertical exaggeration is five-fold. Opportunity investigated the Cape York segment of Endeavour's rim from August 2011 to May 2013, and is now driving to Solander Point. The white line indicates the rover's traverse from Esperance to the rover's location on Sol 3327 (June 3, 2013). For reference, the highest elevation on Solander Point is approximately 55 meters (180 feet) above the surrounding plains. Opportunity is her way to the northern tip of Solander Point to spend the upcoming winter season.NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / OSU

During the last Martian winter, Opportunity positioned itself on a north-facing slope in Greeley Haven at Cape York, and worked from a parked position for more than six months. This winter, scientists and engineers alike are optimistic that the rover will not only work, but be mobile through the harsh season, energetic enough to rove from one northerly slope to another.

Given that the seasons on Mars are generally twice as long as seasons on Earth and because the minimum-sunshine days of MER's sixth Martian winter will be in February 2014, the plan for Opportunity to arrive on August 1st should give the team plenty of time to check out the base of this little mountain, find the right north-facing slope, and outline a winter science campaign.

Despite her age, Opportunity is having no trouble sprinting toward Solander, and no one on the team seems too surprised. Then again, this is "the rover who loves to rove," as JPL rover pioneer Jake Matijevic described this robot field geologist in interviews with the author years ago. "We're making good progress," confirmed Callas.

The skies are hazy over Endeavour, typical of this time of year, and the dust continues to accumulate on the solar arrays, but Opportunity is still managing to produce plenty enough power to make long drives necessary to reach Solander. "Opportunity is doing wonderfully well and she has been practically boring from the standpoint of not having any particular problems," summarized Nelson. "It's the kind of boring we really like."

Other than another annoying Flash memory error on June 12 and some stall issues with her instrument deployment device (IDD) or robotic arm, the rover is in good health and seems, as always, to be raring to go.

The Flash anomaly has happened a couple of times before, the last time some 50 sols ago. "Other than losing a couple of sols work, it was no big deal," said Nelson.

"We recovered the rover, put the sequences back onboard and continued on," added Callas. "Until it's persistent, there's probably not much we're going to do. We'll just deal with it. If happens only once every 50 sols, it's an inconvenience that costs us one or two sols to recover, but it's a small price to pay to keep going on the surface."

The tiger team that was formed in May to look into what the engineers might be able to do to prevent these events, as reported in the last MER Update, continues its investigation, added Nelson. "We're hopeful we can come up with something," he said. "But even if we can't, it's not so terrible that we can't keep going."

In preparation for the work to be conducted at Solander Point, the rover ops team has appointed a group of engineers to look into mitigations for the stalls Opportunity experienced with her robotic arm in June, and what seems to be an errant sensor at the elbow.

As the last week of the month was about to begin, Squyres threw down the gauntlet and challenged the rover planners to have Opportunity log 500 meters (half a kilometer or .31 mile) during the final days of the month. "It's good to set lofty goals," Squyres said.

Alas, because of glitches and no fault of her own, the rover wasn't able to meet that challenge. The robot field geologist did however put a respectable 316 meters on her rocker bogie during June's final week, and 406 meters if you count the drive on June 22nd.

In any case, the rover is now in Botany Bay and racing to the Solander slopes, said Stroupe, as July was peeking over the horizon.

With Solander Point coming into better view with almost every passing sol, the MER scientists are enthralled by what they're seeing in the daily images. "I've been excited about Solander for a long time," said Squyres. "We're seeing more and more structure on the lower slopes, more and more detail and that's a trend that's going to continue."

Given the age of this veteran robot and how much she's been through on this desolate, usually unforgiving planet, the fact that Opportunity is able to pull off these long sprints seems almost crazy. "It's not crazy," said Callas. "It's like your grandfather still getting up every morning and doing a 3-mile run before breakfast. I keep saying this over and over, but it's not how long the rover lasts or how far it's driven but how much exploration we continue to do with this rover - and that's the amazing thing."

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

Nobby's Head

Opportunity used her Pancam to record this view of the rise in the foreground, Nobby's Head on her Sol 3335 (June 11, 2013). The rover drove around the north and west sides of Nobby's Head during a multi-week southward drive between two raised segments of the west rim of Endeavour Crater. This view is centered toward the south- southeast, with Opportunity's next destination, Solander Point, toward the right edge of the view. Nobby's Head is about a third of the way from Cape York, the rim segment where Opportunity worked for most of the past two years, to Solander Point. Opportunity began a trek of approximately 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) from part of Cape York to Solander Point in late May 2013."We're not just wandering around to wander around, as cool as that might be," added Nelson, reflecting. "We're actually finding new things and learning new science about Mars that may have implications for some of humanity's most basic of questions: Where did we come from? Are we alone? The things we're finding out about Mars will help illuminate the answers to those questions. For me, that is one of the really, really exciting things about this mission," he offered.

"These are questions humanity has asked since we ceased to be monkeys and we're getting closer and closer to finding out," Nelson continued. "This mission may not answer those questions, but it is giving us the background from which other missions will draw and eventually find the answers. And that is cool. This has got to be the best job in the world. To have the ability to practically be on Mars - it's as close as I'm ever going to come, most of us on this project will ever come to going to Mars. And, to be a part of a project that has achieved so much and yet has the potential to achieve so much more is really something," he said.

"When I come in, in the morning, I get a daily email with my engineering data from overnight, and putting myself there with the rover and imagining, going through the analysis and telemetry, looking at the rear Hazcam pictures and other images of where we are, knowing what's coming up and where we're going - that's when it really comes home to me - that's when it's always re-amazing," Nelson concluded. "The only thing I regret is that I can't lean down and go - whoosh - and blow off dust from the rover."

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

Opportunity drove into the month of June, logging 62.62 meters (205.44 feet) to officially "arrive" at Sutherland Point on Sol 3325 (June 1, 2013), reported Nelson. After taking three sols to re-charge, conduct routine tasks, and take pictures, the rover racked up another 102.18 meters (335.23 feet) on her Sol 3328 (June 4, 2013). On that drive the rover moved into the apron area between Sutherland Point and Nobby's Head.

"As of Sol 3328, our Year 2013 odometry of 1102.1 meters exceeded the Year 2012 odometry of 1077, meaning that Opportunity traveled further this year than last year," Nelson noted.

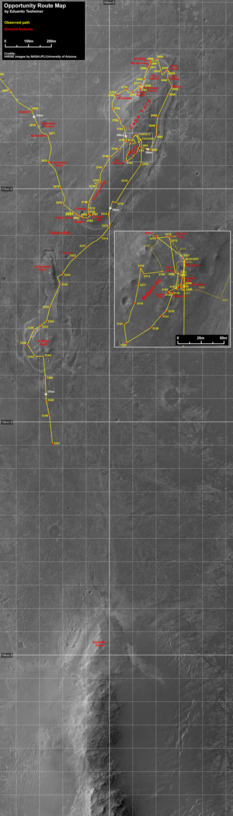

Opportunity route map

This route map, produced by Eduardo Tesheiner, of Unmanned Space Flight.com (UMSF) shows Opportunity's travels around Cape York and through Sol 3351, near the end June 2013, and its current position. Tesheiner creates his route maps, which are regularly featured in the MER Update, from images taken by cameras onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.NASA / JPL / UA / E. Tesheiner

Two days, later, on Sol 3330 (June 6, 2013), the rover put another 65.38 meters (214.50 feet) on her rocker bogie, driving south toward Nobby's Head. From that location, still in the apron area, the robot field geologist began taking images of the north-facing slopes on what is, actually, another smaller section of Endeavour's rim. If for any reason the rover wouldn't be able to make it all the way to Solander Point, Nobby's Head was the chosen "bail-out" option for a winter haven and the engineers wanted plenty of pictures.

Around the same time, the robot field geologist briefly examined the apron to see if it resembled the Bench that surrounded Cape York. "It did," said Arvidson.

With a 30.62-meter (104.06-foot) drive on Sol 3333 (June 9, 2013), Opportunity arrived at the base of Nobby's Head. After spending a sol taking more pictures of Nobby's northerly slopes, the rover put another 34.88 meters (114.43 feet) on her rocker bogie on Sol 3335 (June 11, 2013). The scientists haddecided to take the "scenic route," as Squyres called it, around the far side or western side of the geologic feature.

The following sol, 3336 (June 12, 2013), Opportunity suffered a Flash-memory write error that caused a warm reboot, leaving the rover without a running master sequence. "Basically, the operating system crashed and we believe that was due to the Flash memory problems we've been having off and on," Nelson summarized.

"We did get an X-band fault, because it happened when the rover was using the high gain antenna (HGA)," added Callas. "When it resets, it doesn't record the position of the HGA and that gets flagged as unknown, so the next time we tried to talk with the rover it said - 'Un-uh, I don't know what my system is doing,'" he explained.

The initial recovery attempt on Sol 3337 (June 13, 2013) was not successful, because the rover did not wake early enough to receive the recovery commands. The engineers on the MER ops team were well aware that this might happen, because of variability in the morning wake-up time. But during Sols 3338 and 3339 (June 14 and 15, 2013), they cleared that fault, put the sequences back onboard, and got the rover back into action.

Whatever is going on in Opportunity's Flash memory, it appears now to be different set of glitches than what happened with Spirit. "With Spirit, we had continuous amnesia events," said Callas. "The amnesia event is when the rover wakes up and can't find it's Flash memory, so it works out of RAM, and then when it goes back to sleep, we lose all the information that hasn't been transmitted," he reviewed. "We've had amnesia events on Opportunity, but this anomaly is different."

With Spirit, the MER engineers didn't have a lot of diagnostic information to tell them why the rover was having amnesia, in other words, why her Flash memory would not mount. "But the failure to mount the Flash memory meant that we would build a fallback in RAM, a mode called crippled mode, and when that became a permanent feature, we were able to reformat Flash and remove the bad sectors," recalled Nelson. "Then, we were able to operate Flash, and it was just fine."

On Opportunity, the Flash anomaly occurs when the rover is trying to write things to memory. "It's a different set of circumstances, but it does seem to be [occurring] in the same location in Flash," said Callas.

"We're mounting the Flash just fine, but when we're when we try to write, sometimes it doesn't stick, and we've found a whole peppering of different addresses where this is true, all in the last bank of Flash memory," expounded Nelson.

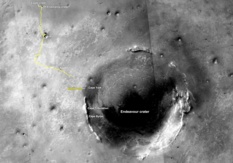

From Eagle to Endeavour

This image of Endeavour Crater was taken by the Malin Space Science Systems' Context Camera onboard MRO. The yellow line on this map shows the route Opportunity took from Eagle Crater, where the robot field geologist landed in January 2004 (at the upper left end) to a point about 3.5 kilometers (2.2 miles) away from the rim of Endeavour Crater. The rover pulled up to Spirit Point on Aug. 9, 2011, after nearly three years of roving from Victoria Crater. Until the middle of May 2013, the robot field geologist worked in the Cape York area. On May 14th, the rover roved on, heading south on a 2.1-kilometer trek to Solander Point, for its next Martian winter. From Cape York, Solander Point is about two-thirds of the way to Cape Tribulation.NASA /JPL-Caltech / MSSS

Since this is intermittent, a reformat now won't fix it, because a reformat can only fix those sectors that are found to be bad at the time of the reformat. "If it's intermittent, then that means some things are not bad at any given time, even though they are bad at another time," Nelson explained. "What's worse, if you reformat multiple times, things you found to be bad before will be rechecked, and if they're good this time, they're restored to the memory. So, you're playing Whack-A-Mole with your problems," he said.

Also, when the engineers do a reformat, they lose everything in memory, just as you would when you reformat your computer. Add to that the week to 10 days it takes to upload all the files back into Flash memory that the reformat takes away and it becomes a time-consuming process. "Reformatting is not the sort of thing you want to be doing all that often, especially since we're racing for Solander Point and trying to make it by August," said Nelson.

As the third week of June took hold, Opportunity continued its half-circle excursion around the far side of Nobby's Head with a 75-meter (246-foot) drive on Sol 3339 (June 15, 2013), during which it completed the first part of a two-sol test of multi-sol autonomous driving. After taking more pictures, the robot field geologist logged a 61.65-meter (202.26-foot) drive on Sol 3342 (June 18, 2013), which contained the second part of the multi-sol autonomous driving test.

Since the rover was ahead of schedule, the science team decided to head east toward the interior of Nobby's Head for a closer look and on Sol 3344 (June 20, 2013), the rover drove for 32.89 meters into the southern interior of this piece of the broken rim of Endeavour.

The scientists were hoping the rover would stop at one of the light-toned rocks there that MER scientists spotted in HiRISE images taken from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. "There was a lot of desire on the science team to stop and take a look at Nobby's Head," said Squyres. "We had the time in the schedule to do some IDD work to if the drive had ended on rock, and just through bad luck, it didn't. The problem was we had worked out how many margin sols we had, how much time we had to stop and scientifically smell the roses along the way, and the margin was getting very, very thin," he explained.

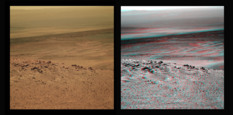

Opportunity's postcards from Nobby's Head

These images, which Opportunity took in mid-June 2013 with her Pancam while roving around the far end of Nobby's Head, were processed, colorized, and rendered into 3D by Stuart Atkinson, MER poet, author, and member of UMSF.com. They are, of course, the same image, near true Martian color on the left, and on the right in simulated 3D. You will need to don your red-blue glasses in order to get the full effect of the 3D image on the right. Also, check out Atkinson's blog, The Road to Endeavour.NASA /JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

Opportunity has consistently had two to three sols' worth of margin since it began the trek to Solander in mid-May. "But our estimates are such that I can't really say if that's real margin or not, because anything could happen to the vehicle," Callas pointed out. "We've picked an approximate date to arrive at our winter haven and the reality is we have to make sure we find the 15-degree slopes and get up on one where we can do science. There are a lot of things to consider, Our performance could bog down, for example. It's just always good to have a little margin," he said.

"It's tough to project ahead and figure out how much margin you've really got," Squyres added. "You've got to guess how far you're going to be able to drive. Some days you drive farther than you thought you would. Other days you have drives that get cut short for whatever reason. We sort of make our best guess and set up some rules and then we have to follow the rules. At Nobby's Head, the analysis we had done suggested we had run out of margin and we had to keep driving, so we did."

That decision took some discipline. "It'd be easy to say, 'Let's roll the dice, it'll probably be okay,'" said Squyres. "But that's not a responsible use of a priceless asset, so when the time comes to make your decision, you abide by the rules you set."

While the data is still being downlinked and will be analyzed in coming in coming weeks and months, Opportunity found that both Sutherland Point, the little peninsula section of the rime of Endeavour, to the north of Nobby's Head, and Nobby's Head are "very soil-covered," said Arvidson. Which means the area has seen perhaps more than its share of Martian winds, among other things.

As Opportunity roved toward Solander, and June roved toward July, Squyres challenged the rover planners and the team to have the robot field geologist blast out 500 meters or a half-kilometer during the final week of the month. "One-hundred-meter drives aren't crazy. This is very flat terrain, very smooth, and we've got good images. We're back on Burns Formation sandstone, terrain we've been driving on for seven, eight years. We've got a lot of experience on this stuff," he assured. ". But if we only get 400 meters for the week," he added, "I'm not going to be disappointed."

A 3D view of Solander Point

Put your red-blue glasses on and check out this image of Solander Point on the horizon that Opportunity shot with her Pancam in June 2013. Note the faint signs of structure on the northern slopes in the upper right portion of the image. "Getting to Solander Point will be like walking up to a road cut where you see a cross section of the rock layers," noted MER Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis. Stuart Atkinson, of UMSF.com, processed this image, and rendered it this simulated 3D image.NASA /JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

On Sol 3346 (June 22, 2013), Opportunity was maneuvering her way back to the rapid transit route to Solander, completing a 90-meter (295-foot) drive due south toward Botany Bay. The rover took a break from driving the following sol to snap some pictures of the rock abrasion tool (RAT) bit to assess how much "bite" the instrument has left. "We are still waiting for those images to be down-linked," reported Senior Systems Engineer Gale Paulsen, who tends to the instrument for Honeybee Robotics and Spacecraft Mechanisms, which manufactured it.

Opportunity was back on the road Sol 3348 (June 24, 2013), driving 96.99 meters (318.21 feet) and well into Botany Bay. "Our ending odometry that sol was 37.028.11," said Nelson. "That drive not only broke 37 kilometers, it also broke 23 miles, and we ended at 37.028 kilometers, about 13 meters beyond 23 miles," reported Nelson. "Not too shabby."

Indeed. Not too shabby for a would-have-been record. While American and Russian teams on Earth continued investigating just how long the Soviet robotic Moon rover Lunokhod 2 actually drove back in 1973, Opportunity stayed clam and in fact seemed to ignore the commotion, and rovered on. A couple of annoying glitches during the last week of June would cause the rover to be unable to achieve Squyres' 500-meter challenge, but the robot field geologist succeeded in getting close.

On Sol 3349 (June 25, 2013), the ops team commanded Opportunity to drive for 160 meters (524.93 feet), but the drive was terminated after only 63 meters (206.69 feet), said Stroupe. "That's okay. These things happen, and it's still more than we need to drive each day."

The reason the drive terminated however was puzzling. It stopped when the potentiometer on the rover's elbow indicated an unexpected motion. The potentiometer is a sensor that can indicate if the arm has moved or is moving during a drive, something that is not intended. But when engineers checked out the joint using before-and-after images, they detected no joint motion.

Opportunity was commanded to drive 120 meters the following sol. But that drive stopped almost immediately, again because of the same potentiometer with an even larger anomalous reading. The ops engineers plan to conduct a set of diagnostics on the joint potentiometer in coming sols.

NASA /JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

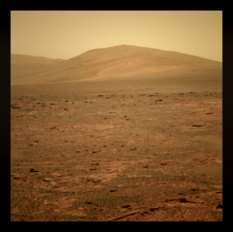

Closing in on Solander Point

Opportunity took this picture of Solander Point, the hill or small mountain in the distance, with her Pancam late in June 2013. The stratigraphy or rock layers are becoming more defined in the images as the rover gets closer. By the end of June, the rover was about halfway to her destination at Solander Point. Stuart Atkinson processed this image.Actually, the MER engineers had already been looking into the joints on Opportunity's arm. "We had a stall in Joint 2, which controls the elevation of the shoulder joint or the up and down movement, of the IDD, and we are working on mitigations for that," said Nelson at month's end. "I'm hopeful that we can deploy those in the next few weeks."

"Those stalls have kept us from placing things on the target on the day we plan to do so, and forced us to take an extra day to recover and place it," Nelson explained. "To have a mitigation of that to keep that from happening will help keep us on schedule, as well as help the rover more efficiently complete its work on science targets."

Meanwhile, the engineers are even looking into the possibility of "reviving" Joint 1, the azimuth joint, which controls the horizontal movement of the IDD, Nelson said. This joint has long been out of service because of stalls. "We have believed that the joint was un-useable, but maybe it's not as dead as we think," Nelson said. "Right now, we are just looking into the possibilities."

Cape Tribulation waits in the distance

Althopugh Opportunity has not yet even arrived at Solander Point, the MER scientists and engineers already have their sights set on the future and Cape Tribulation. Once the Martian winter is over, the robot field geologist and the MER team hope to dig into a motherlode of clay minerals at Cape Tribulation, which have been detected by the CRISM instrument on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Cape Tribulation, a large section of Endeavour's broken rim, lies just to the south of Solander Point. Actually Solander Point is at the northern tip of Cape Tribulation. This image was processed and colorized by Stuart Atkinson, MER poet, author of astronomy books in the U.K., and a member of UMSF.com. Check out Atkinson's blog, The Road to Endeavour.NASA /JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

Finally on Sol 3351 (June 27, 2013), Opportunity managed to bolt, dashing off an impressive 123 meters (403.54 feet). Following that sprint, during the last weekend and final days of June, Opportunity did a touch 'n go, reported Callas. On Sol 3352 (June 28, 2013), the robot field geologist completed the "touch," taking some MI's of an exposed rock called Tawny, then putting her APXS on the same target for an overnight integration. The next sol, she did the "go," with a 31-meter (102-foot) drive to end the month with her odometer at 37.245 kilometers.

At end of June, Opportunity was producing power levels of around 450 watt-hours, just under half of her full capability just after landing - all those years ago. Throughout the month, the rover, recording a Tau hovering around 0.822, worked under hazy skies, able to make use of less than half the amount of sunlight that hit her solar arrays, reporting a dust factor of around 0.605.

The plan ahead is for Opportunity to drive into July and get to Solander Point by August. If all goes well, the robot field geologist will start in on science investigations there right away, even before she drives onto a 15-degree slope. "There's a lot of interesting stuff around the base of the mountain and we want to explore that a bit if we have time," said Stroupe.

With Opportunity getting closer to Solander, the MER scientists are preparing for whatever comes next, and the excitement is building - although it is still somewhat tempered. This experienced team, after all, has experience with this kind of excitement. "We've been through this before," noted Squyres. "As Spirit started to approach Husband Hill, the hills started looking more and more interesting. As Opportunity was approaching Cape York, Endeavour started looking more and more interesting. And now as the rover approaches Solander Point, new details are slowly being revealed to us as we creep up on this thing."

For her part, Opportunity is taking images of the mountain every morning. "We're going to generate another approach movie like we did for Endeavour Crater, and that will be really exciting to see," said Stroupe.

So as June turns to July, all MER eyes are squarely on Solander Point. "We're making more or less the progress we wanted to," summed up Arvidson. "And we're still within the margin to make it by August 1st."

Stay tuned.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth