A.J.S. Rayl • Jun 30, 2008

The Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Spirit Shudders Through Solstice, Opportunity Shoots Cape Verde Base

The Mars Exploration Rovers (MERs) celebrated a landmark milestone in June as they "trudged" through the very depths of their third Martian winter.

“We just passed our third winter solstice on Mars and we're feeling pretty good about that,” said Steve Squyres, the principal investigator for rover science, from his office at Cornell University.

"We're happy with the rovers' overall performance," concurred Jake Matijevic, chief of rover engineering at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where the rovers were designed and are being managed.

Spirit emerged from the winter solstice with more power than anyone expected and Opportunity marked the occasion by roving on, out of the sandpit that snared it back in April and, with its robotic arm in a new configuration, onto the base of Cape Verde at Victoria Crater.

Crossing the milestone is a significant achievement for both robot field geologists and the MER mission. But it is a more significant achievement for Spirit. Because of its location in Gusev Crater, no one ever expected Spirit to survive even its first Martian winter. The solar-powered rover's capability of getting to the Columbia Hills and onto a slope, where it could tilt its arrays to maximize its intake of sunlight "fuel," enabled it to beat the odds. Still, every winter since – and in these recent frigid months – it's been all about survival for this rover.

Toward the end of May and first of June, Spirit's power production levels began dropping to the lowest levels it’s ever experienced, just below 200 watt-hours, or less than one-quarter the levels it had on landing. While somewhat comparable to what Opportunity experienced during the dust storm of June-July 2007, Spirit's low energy proved to be nowhere near as bad or as frightening as what its twin experienced last year.

By hunkering down and putting even its routine science agenda on hold for most of June, Spirit seemed to almost cruise, albeit very cautiously, through the Martian winter solstice and came out with a little power to spare, even though it was experiencing -110 Celsius (-166 Fahrenheit) temperatures at night and -20 or -30- C (-4 to -22 F) temperatures in the middle of the day. "Its current levels are around 230 watt-hours," noted Matijevic, "so it's better than we predicted and we've basically gotten to the bottom of the energy curve, again."

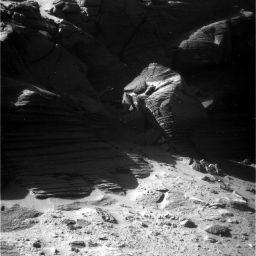

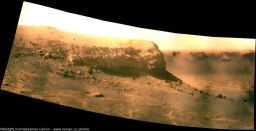

At the base of Cape Verde

At the base of Cape VerdeOpportunity took this raw image just after arriving at its current position at the base of Cape Verde on its Sol 1567 (June 20, 2008). It snapped the image of the geologists' dream cliff with its panoramic camera (Pancam) It may be hard to believe, but the plan is for the rover to move even close to this layered cliff face.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

Granted, Spirit hasn’t completely survived the season yet, but there seems every reason now to believe it will make it through to its fourth Martian spring.

As June gives way to July, it will continue its mellow agenda, riding out winter right where it is on the northern edge of Home Plate. In coming sols, it will return its routine atmospheric research to its daily agenda, and eventually get on with taking the hundreds of images still needed to complete the grand Bonestell Panorama, “as the power permits,” said Squyres.

As good as that news is, "the big event right now," as Squyres put it, is taking place on the other side of the planet, at Meridiani Planum, where Opportunity roved on in June.

With its arm unstowed and held out front, almost proudly, the rover made four drives to back out of the tenacious sandpit in which it had been stuck for some six weeks. Then it turned and drove onward, zigzagging in toward the base of Cape Verde.

Opportunity is currently about 8 to 10 meters (25-30 feet) from the cliff base, depending on whom you ask. For the time being, the exact distance isn't that important. "We're in a beautiful position right now taking a Pancam panorama for the ages of Cape Verde," Squyres said. Opportunity is rising to the occasion, making it worth every bit of robot and human sweat as it sends home "spectacular" images from its panoramic camera (Pancam), the likes of which the mission has not seen before.

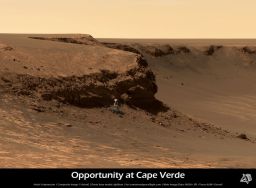

View of Cape Verde

View of Cape VerdeOpportunity looked across the slope and snapped this image of Cape Verde on Sol 1487 (Mar. 30, 2008). The rover is now about 8 to 10 meters from the base of the cliff. For full-resolution version, visit James Canvin's website.

Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell / J.Canvin

"It's been an extremely difficult endeavor," Squyres continued. "We're on slippery, steep terrain and approaching the base of a big cliff that blocks out the sky and casts shadows. That has an impact on all kinds of things, from power to telecommunications, because it blocks out view of the sky from the orbiters."

Even so, Opportunity won't be stopping here. The plan is for it to move in even closer in coming sols.

In other MER news, the rover engineering team at JPL hosted Houston-area Congressman and Mars exploration enthusiast John Culberson this month. The team invited the congressman to participate in the planning of Opportunity's Sols 1557 and 1558 (June 10-11, 2008) and he helped design a science observation of the cobble named Barnes. The target was named, as all the targets inside Victoria Crater have been, for renowned geologists. Barnes honors Virgil E. Barnes, of the University of Texas at Austin.

Spirit From Gusev Crater

When Spirit's power production dropped to 235 watt-hours in late April and Martian winter began settling in, rover engineers knew it was time to really kick into power conservation mode. They disabled the survival heaters on the rover electronics module (REM), because temperatures were falling to a point where they would automatically trigger them to turn on. Since those heaters would command an estimated 60 watt-hours of power, they could easily push the rover past a critical power limit, causing it to drain its battery. Plus, the engineers needed to keep other survival heaters available for the main battery and the miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES).

As the temperatures dropped, keeping the Mini-TES warm was Squyres' "biggest concern," because the science team wants Spirit to use the mineral-seeking instrument come spring to seek new bounties of silica.

Spirit's discovery of near pure silica last year was one of the mission's most significant discoveries, a sure indication of past volcanic activity that featured water, and the source of another milestone paper in Science last month.

But by the end of May, on Sol 1563, Spirit was burning up more energy than ever before on just those heaters – 54.0 watt-hours to warm the Mini-TES and 30.6 watt-hours for the battery.

While the rover was only downlinking data every four sols, when the calendar flipped to June, rover engineers had no choice but to reduce Spirit's activities even further to increase the basic energy performance of the vehicle.

"We changed the planning mechanism," Matijevic said. "We typically base our plans for our vehicles pretty much on the last downlink, trying to get the closest spacecraft status that's possible. Then, we plan with margin from that position on. During the month of May, however, we were in a situation in which the energy levels were kind of tenuous and our power modeling was a few watt-hours out of step with the performance of the system, something on the order of 10 to 15 watt-hours. That's a big deal when you're only pulling 220-230 watt-hours," he pointed out.

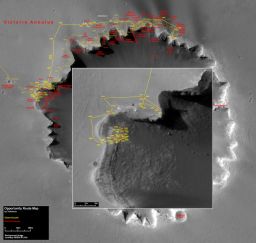

Spirit explores Home Plate

Spirit explores Home PlateMore than a year of Spirit's investigation of the feature in Gusev Crater known as Home Plate is chronicled in this animation of nine images from the HiRISE camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). The images cover an area approximately 100 meters square. The geometry of Home Plate appears to shift from image to image because the orbiter often had to turn to one side or the other of its orbital track across Mars in order to view Spirit, so usually saw the raised topography of Home Plate from a point that was not directly over Spirit's head. However, some of the apparent shifts in features are also real shifts in the distribution of dust around Home Plate with shifting winds and seasons. The dust storm of summer 2007 almost completely blocks the view of Spirit at one point during the animation.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / D.Ellison

"You can have a fair amount of variance and your plan can be off in an energy-negative way if you're not accurately estimating where the array is going to be and the battery charge is going to be at the time of lowest dip in the state of charge, especially when we're doing more energetic activities like communication," Matijevic added.

While the rover engineers have been “rapidly correcting” those models, the difficulty has been in trying "to predict the energy projection and also what the survival heating requirements will be," Matijevic said.

In part, it's difficult because the rovers don't carry weather stations and predictions of external temperature conditions are not always exact. “Depending on what assumptions you make about what the external temperatures will be, you can get a different prediction as to how much survival heating is needed," he said.

As Spirit carried on, the rover engineers discovered the rover had started to run down its main battery. "It wasn't a very fast degradation, something like a couple of tenths of an amp hour, but it was pretty persistent over a period of a few weeks," Matijevic said. At the same time, the rover was requiring more power for the survival-heating requirements of the Mini-TES and the battery of “up around 90 watt-hours,” he said. "We took a step back and decided we could not do that any longer.”

Although Spirit experienced the lowest power levels it ever has in June, those levels were certainly not the lowest the mission has experienced. Opportunity suffered even lower power levels, as low as 125 watt-hours on one sol during the global dust storm in June-July 2007. So Opportunity still holds that record and the engineers want to keep it that way.

They decided Spirit would put all science on hold. “Then, we put together a very lean engineering plan," said Matijevic. “We were creating plans that had very little content in them and even separated planning from the downlink. The thought was that with the plans pretty much empty of activities, the rover was likely going to be power-positive as a consequence."

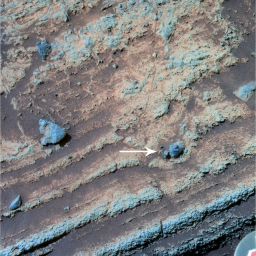

Volcanic Home Plate

Volcanic Home PlateSpirit took this false color image of an edge of Home Plate with its Pancam. It shows some of the evidence on which the science team is basing its hypothesis that the circular plateau was created from volcanic activity. The lower coarse-grained unit shows granular textures toward the bottom of the image and massive textures. A feature interpreted to be a "bomb sag," which is four centimeters across, is pointed out.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / USGS / Cornell

Spirit followed the new strategy, spending most of the month of June "chilling." For three weeks, the rover planners (RPs) uplinked 7-sol plans, Matijevic said. These plans included one sol in which the rover worked for about 30 minutes, "handling basic engineering activities and maybe take a tau measurement," with another sol in the week devoted just to downlinking data, and five sols dedicated to re-charging, maintaining the ability to send new commands if needed. “We were trying to keep the vehicle asleep most of the time."

This meant that for one of the rare times on the MER mission, Spirit wasn't even conducting its routine dust monitoring or atmospheric observations. Virtually all science was put on hold. Fortunately, dust wasn't much of a concern since the deposition on the solar panels has been “flat, with very little if any change in the last month," said Matijevic.

As Spirit headed toward winter solstice on June 25, the temperatures at Gusev Crater had dropped to an estimated -110 Celsius (-166 Fahrenheit) at night, rising to as high as -30 degrees C (-22 F) during the middle of the day. "In order to conserve energy, the vehicle has not been awake for very long because it can't be, so we don't get a lot of readings for external temperatures. We're trying to piece the readings we do get against models in the past and so these are not exact figures."

Nevertheless, Spirit not only succeeded in conserving what power it had, but actually managed to boost its levels to emerge power positive as had been anticipated during the planning of the power conservation strategy. “We regained our battery state of charge and the energy levels for the spacecraft bumped up to about 230 watt hours, which is where it's held now for the last two weeks," said Matijevic. "So in the course of a three-week period of time we actually gained.”

Looking northward

Looking northwardSpirit took this image with its Pancam on Sol 1448 (Jan. 29, 2008) after inching backward into position just off the edge of the northern edge of Home Plate. This is the view it has enjoyed since and will enjoy at least until September or October 2008, when spring "blooms" in the southern hemisphere of Mars. Husband Hill is on the horizon. The dark area in the middle distance is El Dorado sand dune field. This picture combines separate images taken through the Pancam filters centered on wavelengths of 753 nanometers, 535 nanometers and 432 nanometers. It is presented in a false-color stretch to bring out subtle color differences in the scene.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

Spirit's "primary objectives" for June had been "environmental monitoring and keeping the vehicle safe and ready for spring," as Squyres said last month. Like a true MER, the rover has come through again, achieving those objectives "much better than any of us expected," he summed up. "And, we haven't had to touch the Mini-TES survival heater."

With its newfound energies, Spirit has been slowly adding some routine dust monitoring and atmospheric work back into its agenda. It has also increased communications. “With the results we had of putting energy back into the batteries and being at these power levels, we changed the planning cycles to two uplinks a week and downlinks once every four sols,” noted Matijevic.

For now and in near-future sols, Spirit will continue to focus its science time primarily on atmospheric monitoring and dust monitoring. Tau measurements of the amount of dust in the atmosphere provide valuable data for science and operations planning, because, perhaps obviously, they affect the amount of solar energy that reaches the rover's solar panels.

The Bonestell Panorama – Spirit next majestic winter panorama, which will be comprised of some 2,000 images – is "still in work," said Squyres. "Plans will be added in to continue taking those Pancam pictures when we've got the power to do it. “

Robotically speaking, "everything is fine," said Matijevic. Spirit remains in good health, with subsystems performing as expected.

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

Testing Opportunity's robotic arm

Testing Opportunity's robotic armDuring Sols 1531-1,532 (May 14-15, 2008), Opportunity's handlers successfully deployed its stuck robotic arm, then determined the rover will have to drive from now on with its arm position out front is what the engineers call a "fishing pole" configuration.

Credit: NASA / JPL / animation by E. Lakdawalla

On the inner slope of Victoria Crater not far from its entry Point at Duck Bay, Opportunity greeted June in nearly the same place it left April, stuck in a tenacious sand pit that tripped it up back in April as it was heading for the base of Cape Verde. In fact, the rover took its first drive to back out of the sandpit on the last day of May.

That short, less-than-a-meter drive marked the first time in six weeks that the rover had moved since it inadvertently rolled over a ledge and encountered the sandpit. When it began unstowing its arm, its shoulder joint broke, so while its ground team dealt with the issue of the broken arm it was left to take panoramic images of nearby, conduct atmospheric research, and not move.

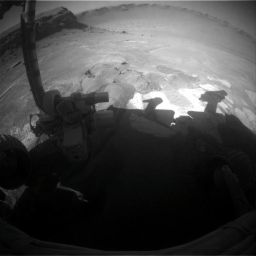

As June took hold, the engineers knew from weeks of testing in the Mars Yard at JPL, that Opportunity could drive with its arm partway unstowed and continued experimenting with the best possible configurations. They agreed the best position was for Opportunity to hold its arm out front, so that it kind of looks like it has permanently gone fishing.

"If you think of a fishing rod, its high point is above the stream and the line is below it, and it [presents] an angle," said Matijevic. "In a very similar sense, the rover's arm is in that kind of position. The elbow is up, almost at the level of solar panel, and the arm then extends, from the shoulder to elbow, then from elbow down to the effector, forming a right angle or L-shape. Therefore, it's kind of like a fishing pole, with the instruments sitting above the rover's bellypan."

In this position, the arm doesn't interfere with Opportunity's mobility capabilities. Moreover, it appears that in this "fishing pole" configuration, the rover can drive pretty freely without radically moving or doing damage to its arm, said Matijevic. It can even handle the slips and slides that come with driving on the sloped surfaces inside Victoria Crater. "We tested the rover engineering model with both backward and forward wheels falling off ledges and the impact was pretty much the same," he said. "We could create vibratory motion on the arm, but that was all that took place."

Opportunity's new arm position

Opportunity's new arm positionAfter a problem with Opportunity's shoulder joint rendered it unreliable, the MER team was forced to regroup and direct the rover to drive from now on with the arm unstowed. Opportunity took this image, which shows the arm in its new driving position, on Sol 1562 (June 15, 2008) with its navigation camera.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

It was, simply, the best of news for Opportunity in June. The sandpit, however, turned out to be “quite a bit larger and deeper" than had been expected, said Matijevic.

"Opportunity couldn't back up very far away from it, because it was over this ledge and wasn't getting very good traction," he said. "So we spent a certain amount of time thinking through what was the best approach here."

At the time Opportunity first entered Victoria Crater, the RPs were given instructions to always follow forward drives with a backward step or two to verify any drive performed could be un-done by backing up.

"It's done this all the way down the crater," said Matijevic. "The RPs have followed those driving rules carefully. To extract Opportunity from this sandpit over a ledge, they would have to back up so the vehicle was solely on bedrock and it was determined that's what should be done.

During the first week of June, the rover also conducted a series of shadow tests to determine the best way to photograph Cape Verde in the blocked-light conditions at the base. The position of the Sun as it arcs across the in the sky causes the cliff to cast extensive shadows during the day, as mentioned in previous MER Updates. These shadows impact not only imaging, but access to the solar-powered rover's "fuel" and communications if the orbiters pass by and the rover can’t see them.

Nevertheless, throughout the month, Opportunity managed to receive morning instructions directly from Earth via its high-gain antenna and downlink data daily via Mars Odyssey, as well as conducted its daily measurements of atmospheric dust.

Opportunity also spent quality time at the top of the month snapping full-color Pancam images of the cobble called Agassiz, taking six-frame, time-lapse "movies" of potential clouds passing overhead with the navigation camera, and measuring argon gas in the Martian atmosphere with the alpha-particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS), part of an ongoing, long-term study.

Out of the sandpit

Out of the sandpitOpportunity took this picture with its front hazard camera on Sol 1557 confirming that it had finally backed completely out of the tenacious sandpiut that had it in its grips since April. In this image, the rover has successfully gotten all six wheels back on bedrock. The sandpit is visible just above the robotic arm or instrument deployment device (IDD), which is shown here in the new "fishing pole" configuration.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

Finally, on Sol 1552 (June 5, 2008), it drove backward again, less than a meter, pushing to get fully out of the sandpit and back on bedrock. The rover took the usual post-drive pictures, then with its hazard-avoidance cameras it took some images of the cleat marks it made with its wheels cameras, and with its navigation camera it collected images for a mosaic. It was beginning to escape the clutches of the Martian sandpit.

“It took several drives to back up enough so that the wheels were on bedrock," Matijevic said. In between those drives, as the second week of the month got underway, Opportunity continued its science research, using its Pancam to survey surrounding rock clasts and take full-color images of Barnes and its navigation camera to search for clouds.

On Sol 1557 (June 10, 2008), Opportunity took its fourth and final drive backwards and finally got all six of its wheels back on firmer ground. It took another set of post-drive images, then after sending data to Odyssey, measured atmospheric argon with the APXS. It was a long sol for Opportunity, but a good one. Plans for the following morning called for it to monitor dust on its mast and take another six-frame "movie" in search of clouds passing overhead.

After several more sols of atmospheric research and Pancam imaging from its position near the sandpit, Opportunity turned and roved toward the base of Cape Verde, about. "From Sol 1562 to 1567 (June 15-20, 2008), the rover made six different drives on six different sols," said Matijevic.

The drives put 23 meters onto Opportunity's odometer, though the distance to its present location was only 15 meters. "It did not take a direct route, but zigzagged, trying to find paths that could reduce the amount of slip and also get us into position so that the rover would be facing a more northerly direction, deemed the best for the imaging campaign," said Matijevic.

While each of the drives out of the sandpit were backward drives for reasons explained above, each of the roves toward the base of Cape Verde were forward drives. The stability of the Opportunity's arm through all the driving this past month has been something of a surprise.

"At the same time, one of the things that is true about this vehicle is that there is quite a bit of acceleration and/or forces that are assumed by the wheels as it drives around," Matijevic pointed out. "The design of the rocker bogie system basically takes out or attenuates a lot of the forces that go into the vehicle as a consequence of its moving around on the surface."

A suspension system developed back in the 1980s by JPL engineer Don Bickler while working overtime in his garage, the rocker bogie system was first demonstrated on Mars by Pathfinder's tiny, microwave oven-sized rover, Sojourner. The term "rocker" comes from the design of the differential, which keeps the rover body balanced, enabling it to "rock" up or down depending on the various positions of the multiple wheels. The term "bogie" hails from old railroad systems, specifically the train undercarriage that features six wheels that can swivel to curve along a track.

"The motion from driving that is imparted to the web box and to the connections to the web box, which is the arm, is much reduced with the rocker bogie system, something on the order of 8 to 1 or 10 to 1, depending on the forces involved," said Matijevic. "So the actual motion the arm or the IDD sees is much less."

Interestingly, from the tests in JPL's Mars Yard, the rover arm really didn't move much at all. "It would shake a little, but it didn't change position," said Matijevic. "And that's what we've found in the performance of 10 drives over the course of the last three weeks. We have not seen any motion of the arm. It's been in exactly the same position after every one of these drives.”

Opportunity is currently between eight and 10 meters from the base of Cape Verde, depending on "what you consider the actual base," as Squyres put it, and is in the midst of its picture-taking campaign of the cliff face and its surroundings.

"It's been very interesting actually," offered Squyres. "I never thought that more than 1,500 sols into the mission that we'd be learning new things about how to take pictures with Pancam, but we've never had to take pictures of Mars looking up before. Now we're looking up at this cliff, so we're dealing with things like Sun glint that haven't shown up in our images before. It's a matter of taking the pictures at the right time of today, but we had this very interesting session [last Thursday] where we had to re-shoot four images out of a mosaic because of too much glint. We've just never seen that before," he said.

As tedious and troublesome as it may seem, it is, said Squyres, "what we should be doing at this stage of the mission. We've done the easy stuff and it's time to do the hard stuff. This is one of the hardest things we've ever tried. We're having a ball with this."

Although Opportunity bounded into June sporting energy levels up around 450 watt-hours, its power production dropped over the last four weeks. "Now that it's moved in toward the cliff base, it is uphill and at a 12-degree adverse tilt toward the south and averaging around 370 watt-hours," said Matijevic. At this point, no harm, no foul. "We still have plenty enough energy for what it's doing and all subsystems continue performing as expected," he assured.

The plan for Opportunity now is to finish the big "Cape Verde Panorama for the ages" and follow that with some super resolution imaging of a number of selected targets on the cliff face.

"Then, we're going to move in closer," said Squyres. " We have to worry about mobility, wheel slippage, and we have to worry about power. We don't want to drive into the shadow of the cliff and we don't want to get into too adverse a southward tilt. But we're going to get as close as we safely can."

The MER science team has its collective eye on the rover's next desired destination. "We've got a name cued up, but we're not going to use it until we get there," said Squyres. It falls into the same theme they've used all along inside Victoria Crater. [Think renowned geologists.]

If everything goes as planned, and as well as it is now, Opportunity should be roving closer toward the cliff face sometime this week. "We have to kind of drive uphill to make a closer approach to Cape Verde and we're still determining just how much closer we can get," Matijevic said.

However close Opportunity actually does get, said Squyres, "it'll be the closest we've ever gone – or will go – to a big cliff."

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth