Emily Lakdawalla • May 23, 2006

Cassini RADAR: Another Flyby, Another Completely Different View of Titan

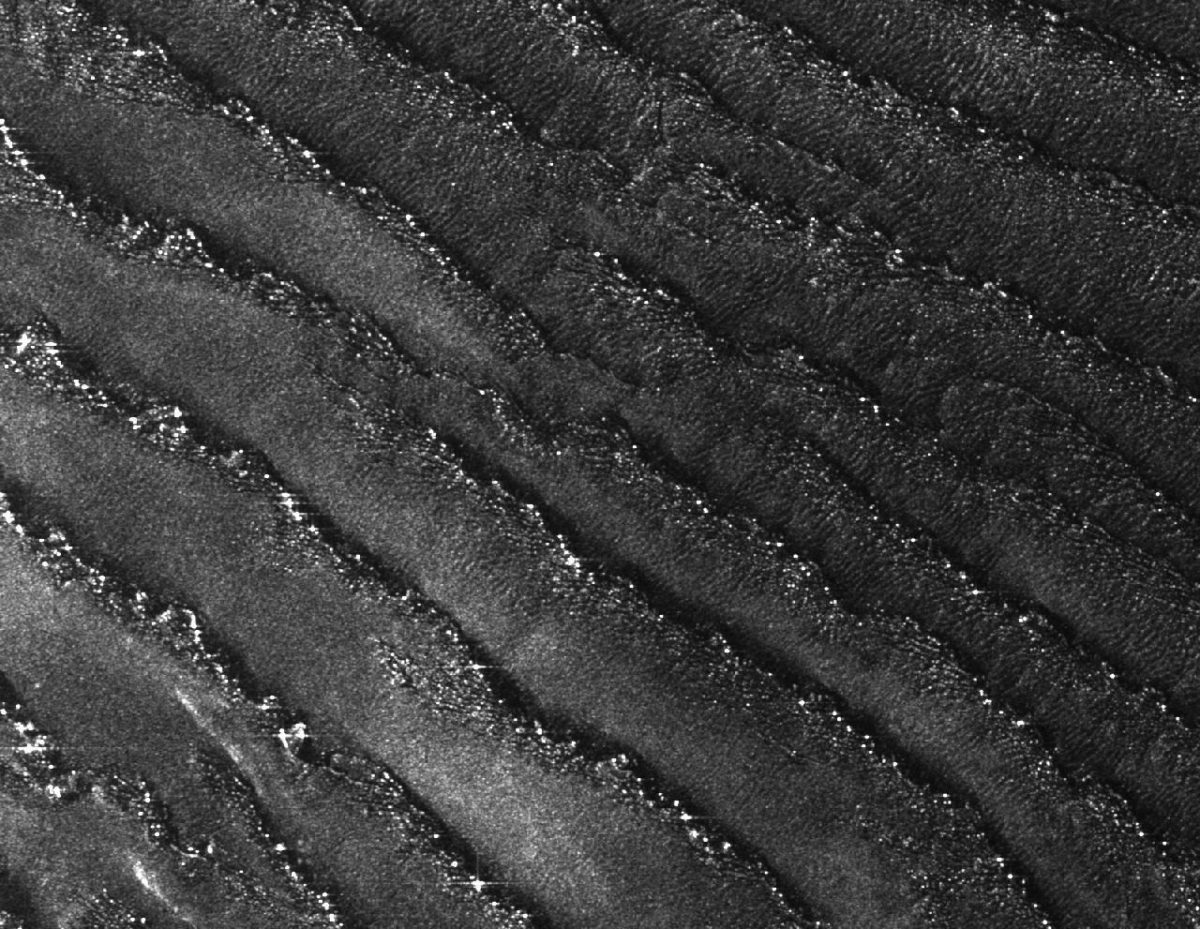

OK, I finally got a story written about the latest and greatest of the Cassini RADAR data based upon a conversation I had with with Ralph Lorenz late last week. He had a few interesting comments that didn't quite fit into the context of the article, so I'll put them in here. First, he has been staring very hard at Shuttle Imaging Radar views of sand dunes on Earth, particularly those in Namibia, as analogues to what he's been looking at on Titan. And he stated the perennial lament of any geologist who has to work from satellite images: we could see so much more if we just had a bit better resolution. On Earth, these Namibian dunes look very much like the Titanian ones at low resolution -- long, skinny, straight, parallel sets of dunes aligned with the average wind direction. At high resolution though, "You can see little transverse dunes in between the longitudinal ones, you can see lots of little glints from small dunes on top of the longitudinal ones. And where the longitudinal ones taper out to a dark apex or dark triangle, much like the ones on Titan do, in Namibia you can see these tapered parts where there's little collections of star dunes, where the wind pattern is evidently a bit more complicated. So there's an awful lot that we're not seeing on Titan that we could see if we were there with either a high-resolution radar on an orbiter, or on a balloon with a camera."

Ralph, of course, was the guy who gave the Titan Montgolfiere presentation at the Outer Planets Assessment Group meeting two weeks ago—he is very seriously interested in seeing a balloon with a camera go to Titan in his professional lifetime. I asked him what we could manage from orbit. He said, "Terrestrial civilian radar routinely achieves 10-meter resolution. But they can be lower in their orbital altitude than we'd have to be on Titan, because Titan's atmosphere is very thick. Realistically, 50 meters; 100 meters is a piece of cake. 50 meters could be done with some effort, we might do better than that."

Speaking of "some effort," Ralph had some tantalizing things to say about what to look forward to from the RADAR team. "The RADAR imagery is bringing up new surprises every time. The processing and techniques we're applying are getting better all the time. We're finding ways of getting little bits of imagery from even further away than we planned, and we're starting to get a handle on the altimetry side of things too, so it's all good." Altimetry, I asked? The public hasn't been shown much altimetry data from the Cassini RADAR instrument yet. There is supposed to be a little burst of altimetry data on each end of the SAR images, so there should be data available; the fact that we haven't been shown it indicates that the RADAR team is not finding it as easy to calibrate their altimetric data as it is to produce the SAR images, which they seem to be able to spit out within hours or days of a flyby. Ralph laughed and said "There's a story developing but that's all I can tell you. The guys are basically doing things that we've got no right to get away with doing with SAR data but the results may be worth sticking our necks out for."

It's common for workers on a long-lived mission like Cassini to be able to spend a few years working with their instruments and slowly develop new techniques that they had, as Ralph said, "no right to get away with" or at least no right to promise going in to the mission. Just look at Malin Space Science Systems and the performance they've managed to pull out of MOC on Mars Global Surveyor -- they now routinely produce images with resolutions down to 50 centimeters (several times better than they'd initially promised) and are accomplishing tricks like catching photos of other orbiting spacecraft. So I've no doubt we'll see some similarly great tricks coming out of the Cassini teams in the coming years.

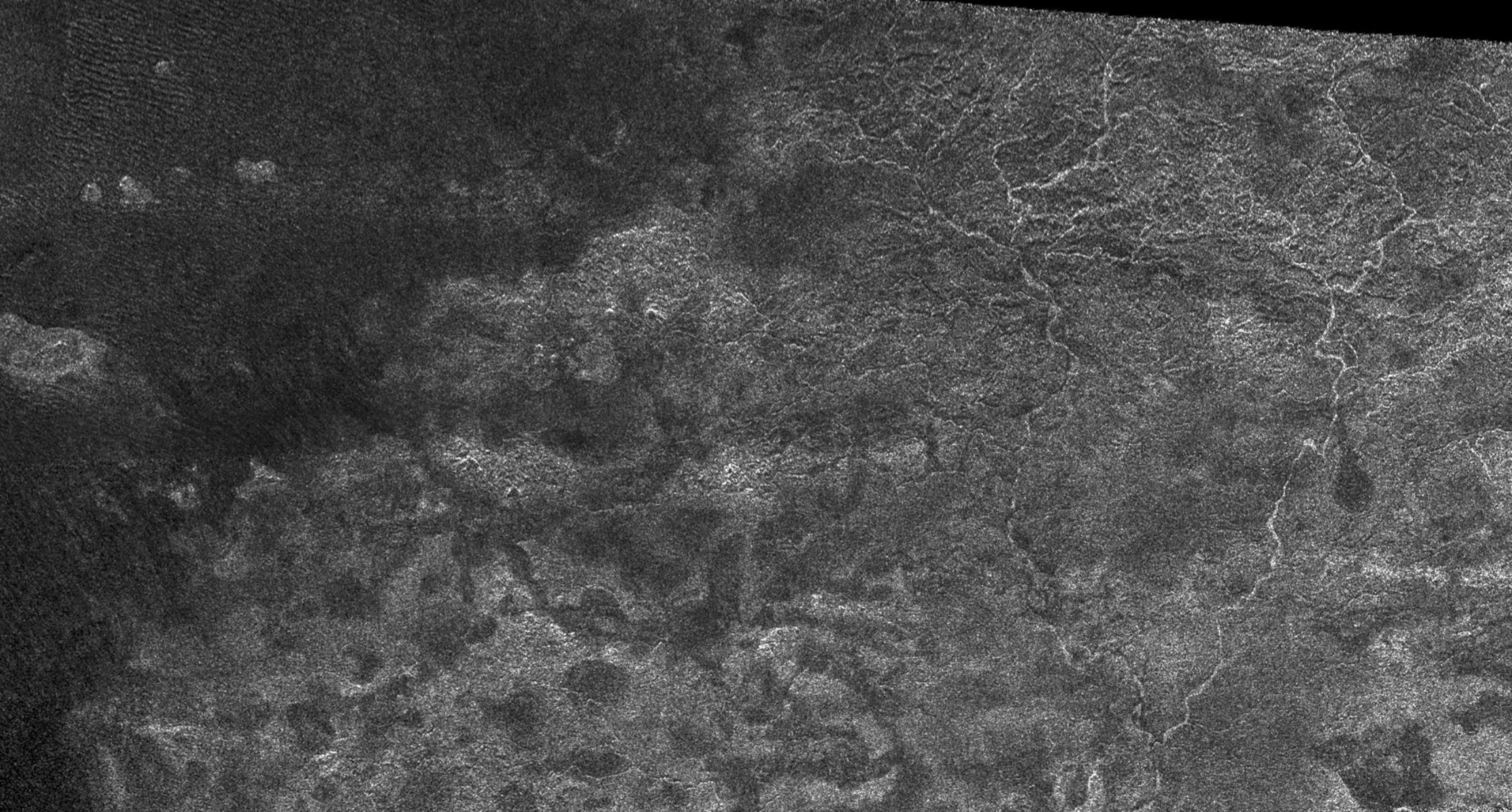

On a slightly different topic, I wanted to point out the final image that I included in the story. I kept the original image title that accompanied the image when it was released:

I sometimes keep and sometimes change the titles of the images released by JPL, but I had to keep this one because RADAR team member Rosaly Lopez was so proud of the literary reference she had sneaked into it. (She told me this -- twice -- at the OPAG meeting.) The image's title is a reference to the opening stanza of Samuel Taylor Coleridge's poem "Kubla Khan," which she, and I, and, I assume, millions of other people had to commit to memory as kids:

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth