Casey Dreier • May 20, 2014

No, Russia Did Not Just Kick the U.S. Out of the Space Station

Update 2014-05-21: Updated Rogozin's statements below with official english translation (replacing poor Google translation).

In a surprise series of statements last week, Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin announced that Russia would stop shipments of rocket engines unless the U.S. could guarantee that they would not be used to launch military spacecraft. He also implied that the Russian space agency would not support the proposed extension of the International Space Station through 2024.

And oh man was this news seriously misreported.

"Russia is kicking NASA out of the International Space Station in 2020," hyperventilated Vox.com. "Russia Wants to Ban U.S. From the Space Station, But NASA Knows Nothing About It," according to Mashable. Even Stephen Colbert misreported the story (because he was quoting NBC Nightly News and Fox News).

Not everyone got it wrong (and, to generalize, it was mainly click-hungry news aggregators and TV news that blew it out of proportion). Pete Spotts at the Christian Science Monitor really provided excellent context for the story, as, of course, did Marcia Smith at Space Policy Online and Warren Ferster at SpaceNews.

There are two separate issues here, one relating to the engines and one relating to the space station. Let's start with the one that got most of the news this week.

The ISS

The International Space Station (ISS) contains significant hardware contributions from Russia, the European Space Agency, and the Japanese Space Agency, among others. But Russia is the largest partner and its contributions are crucial to the basic functionality of the station, which include providing the primary means for station propulsion (it periodically needs to boost its orbit due to atmospheric drag).

Though the ISS has been continually inhabited since 2000, it was only fully completed in 2011. For years previous, NASA (and the U.S. Congress) had only committed to operating the space station through 2015. It wasn't until the 2010 NASA Authorization Act that NASA was directed to continue the ISS through 2020 (with a lot of support internally from NASA).

But it wasn't until January of this year that the White House proposed to extend ISS operations through 2024. To date, no other country has officially agreed to this extension, though it was widely believed that Roscosmos was supportive of it.

Obviously, that's no longer the case, at least from an official level. Here's the relevant quote from Rogozin's recent press conference (official translation):

As for the International Space Station (ISS), this is an extremely sensitive issue. We were somewhat surprised, if not amused, by the fact that the United States is prepared to reduce cooperation in every area with the Russian Federal Space Agency, except the ISS. Basically the US wants to keep those areas it’s interested in, but it’s ready to take its chances in other areas that are less interesting for them.

We also realise that the ISS is quite fragile, both literally and figuratively. This concerns manned space missions and the life of the astronauts, and we’ll therefore proceed extremely pragmatically and will not hamper the operation of the ISS in any way.

However, it should be kept in mind that, by creating problems for us, for the Russian industry developing launch vehicles that can fly Russian cosmonauts and US astronauts to the ISS ... It is absolutely obvious that this is some kind of logical inconsistency on the part of the United States. The US creates obstacles with regard to launch vehicles and evacuation systems. But at the same time, it believes that the ISS should not be tampered with. Our US colleagues have told us that they would like to extend the ISS' operation deadline until 2024. But the Russian Federal Space Agency and our colleagues, including the Academy of Sciences and the Russian Foundation for Advanced Research Projects are now ready to make some new long-term strategic proposals linked with the subsequent development of the Russian space programme after 2020. We plan to use the ISS exactly up to 2020.

Notice he did not say that they would "kick out" the U.S. or stop launching astronauts to the station anytime soon. It's not even clear what the exact consequences of withdrawal would be (could the U.S. take over control of the Russian segment?) As John Logsdon of GWU's Space Policy Institute noted, it's unlikely that the Russians could run their segment of the station without the U.S. hardware, either. There's a lot to figure out.

But there are no immediate threats to U.S. access to the space station. That bears repeating.

NASA issued a statement not long after Rogozin's remarks saying, basically, that they hadn't been notified of this in advance:

Space cooperation has been a hallmark of US-Russia relations, including during the height of the Cold War, and most notably, in the past 13 consecutive years of continuous human presence on board the International Space Station. Ongoing operations on the ISS continue on a normal basis with a planned return of crew tonight (at 9:58 p.m. EDT) and expected launch of a new crew in two weeks. We have not received any official notification from the Government of Russia on any changes in our space cooperation at this point.

I don't want to totally downplay these remarks—they are inflammatory and are certainly causing some major headaches within NASA. Congress is already requesting information on what NASA is doing to preserve ISS access. These statements should be taken seriously. But I do want to note that six years is a long time in politics, and a lot can and will change between now and 2020, including at least one Presidential administration.

Also worth mentioning is that NASA plans to have its Commercial Crew program launching astronauts to the ISS starting in 2017, a full three years before the potential Russian withdrawal. The Senate has yet to release its proposed NASA budget for 2015, and given these new statements, I predict that Commercial Crew will receive a healthy allocation, likely above the $785 million provided by the House in their draft budget.

Again, I need to emphasize: this has no immediate impact on ISS operations that we yet know of. Russia is still planning to launch U.S. astronauts to the space station and return them safely (and did, just a day after Rogozin's statement). Remember, Russia makes money launching U.S. astronauts right now—about $71 million per seat. And like NASA, they have no other human spaceflight program. The space station is it, and unless they're willing to throw away that investment and that income, the space station will serve to temper actions despite the rhetoric.

The Other Problem: The Ban On RD-180s

Now the other policy decision announced by Rogozin stands to be more disruptive, though it also has no immediate impact. It's the ban on Russian-made RD-180 rocket engines for use in U.S. military launches.

Like most people, you are probably wondering why Russia is involved with U.S. military launches at all. Well, it's because of the Atlas-V rocket.

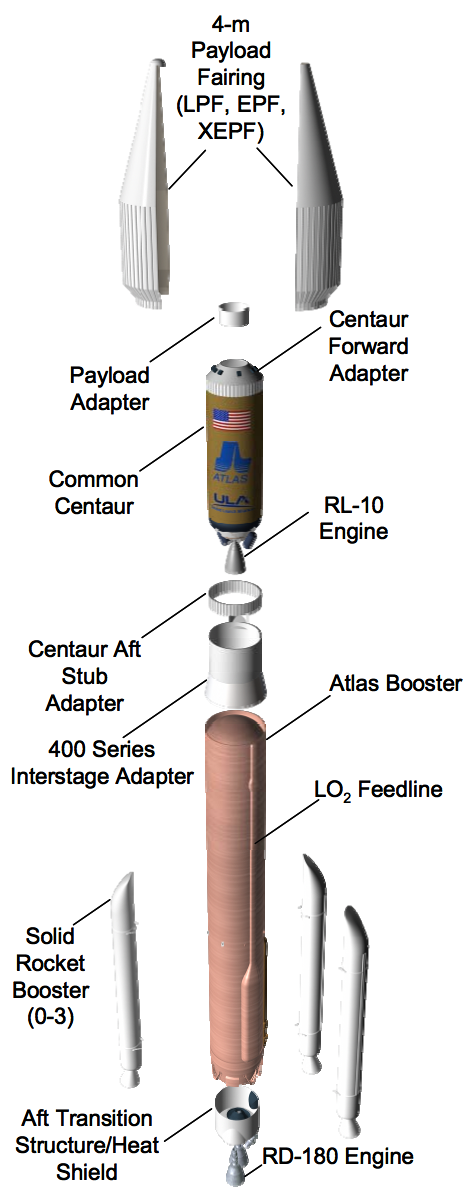

Russian-made RD-180s are used as the first stage engines in the otherwise U.S.-made Atlas-V, one of the two rockets used by the U.S. government to launch nearly every uncrewed spacecraft (the other rocket is the Delta IV).

The Atlas is made by a company called the United Launch Alliance (ULA), which is a joint venture between Lockheed-Martin and Boeing, and, at the moment, the sole provider of rockets for national security needs. The ULA also launches the majority of uncrewed NASA missions (resupplying the space station is a notable exception). The Atlas-Vs are very reliable but also very expensive. For example, NASA is paying about $160 million for an Atlas-V to launch its next mission to Mars, InSight, for which the spacecraft and two years of operations have a total budget of about $450 million.

Regardless, the Atlas uses the RD-180 and now Rogozin says that Russia will stop exporting them to the U.S. unless the ULA guarantees that they won't be used in national security launches. This is very unlikely. So what happens now?

Again, the immediate impact is mitigated because the ULA has 16 RD-180 engines already in the United States, and they claim that this gives them up to two years' worth of buffer for things to simmer down between the U.S. and Russia. As of this post, the ULA has not received any additional confirmation that this threat has come to pass (they have four engines currently on-order for delivery this year), though at this point I don't see how Russia could not follow through, at least for a while.

If Russia stops the shipments, the Delta IV can be used as an alternate rocket. This isn't ideal though, as the Delta IV is significantly more powerful than the Atlas-V, and significantly more expensive—around $350 million per launch. It's also not clear how quickly the ULA could ramp up production of this rocket, either.

It's also looking likely that the Department of Defense will begin to develop their own RD-180 replacement. But that will take at least a few years and cost on the order of $1 billion.

And then, for what I assume many of you are wondering, there's SpaceX and their Falcon 9 rocket. This whole issue falls between an pretty major power struggle for the future of the U.S. government launch market, with SpaceX trying to compete with ULA for national security launches. I'm not going to delve too much into this, save for the fact that there has been litigation by SpaceX against the Air Force, protests against big "block buy" contracts given to the ULA, and lots of accusations exchanged between both companies about risk and cost and value to the taxpayer.

SpaceX has been warning Congress about Atlas-V's Russian engine dependence for some time now, and this recent move by Rogozin pretty much plays directly into their narrative. The problem is that SpaceX is not yet certified by the Air Force to carry military payloads (they're working on it) and it's unclear if the Falcon 9 can launch NASA missions, like InSight, to Mars (which is a significantly different requirement than launching something into low-Earth orbit).

For the Society's interests, we're particularly worried about how this situation is going to impact the flights of two planetary exploration missions in 2016: OSIRIS-REx and InSight. Both missions are planned to launch on Atlas-Vs. My gut tells me that if it comes down to military necessity vs. Mars exploration, the military will get those Atlas-Vs over NASA.

Why This Is Happening

In a word: Crimea.

But in a lot more words: this is another step in an escalating series of reactive policy decisions between the U.S. and Russia caused by Russian interference in Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea.

In early April, the U.S. broke most ties between NASA and their counterparts in Roscosmos, though the International Space Station was specifically exempted in this directive. While this was widely (mis)reported as coming from NASA, this seems to have been an Administration-wide policy that applied to all federal agencies and their Russian counterparts.

The Obama Administration has also been levelling targeted sanctions against high-ranking individuals within the Kremlin, of which (surprise!) Dmitry Rogozin was one.

So this seems to be a retaliatory move in response to these and other sanctions. Note that so far this is mainly rhetoric. None of this is immediate. I hope that the inter-dependency between Russia and the U.S. on human spaceflight acts as a stopgap, or at least a road bump, to allow time for tensions to simmer down and for real progress to be made.

So don't start freaking out just yet. Should you be concerned? Yes. But a lot has yet to happen before we see real impacts from Rogozin's statements.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth