Emily Lakdawalla • May 17, 2017

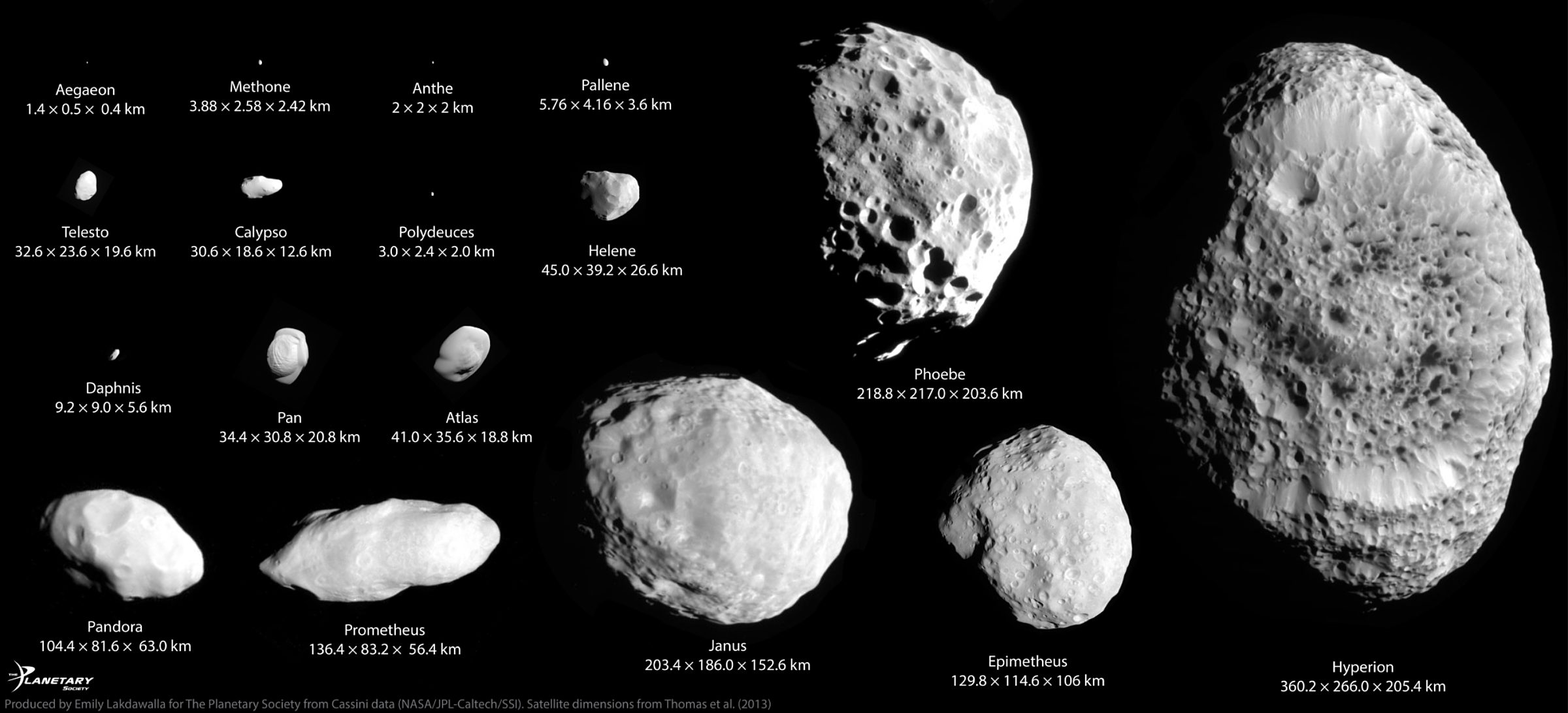

Saturn's small satellites, to scale

Early in 2017, as Cassini began to circle the drain on its Saturn orbits, it was able to capture several images of the tiny, odd-shaped ring-moons from closer perspectives than ever before. I find it really hard to wrap my head around all the scales in the Saturn system so I thought it was time to produce another of my patented size comparisons of planetary bodies. As it turns out, there are orders of magnitudes of scales in the Saturn system and it wasn't sufficient for me to produce one such size comparison.

Here's the first comparison I produced. When you enlarge it to its full resolution, it has 100 meters per pixel. These are all the smallish moons in close orbits around Saturn (with the exception of Phoebe, which is a bit out of place here, representing all the wayward irregular moons in distant orbits). It's astounding to me how much diversity and size variation there is even among Saturn's smallest moons. There's this weird transition from lumpy to smooth that happens at the very smallest sizes, where the tiniest moonlets appear to be covered with a gravity-smoothed, deep coating of ringsnow that must be the puffiest substance imaginable. I'll bet you could fly right into the outer layers of one of those moons and sploof out the other side, leaving in your wake a super-slow-motion eruption of fine ringsnow material that the motion of your passage produced.

It's difficult to tell in this comparison, but I cheated on Aegaeon, Anthe, Pallene, and Polydeuces, using Methone to stand in for them all, because it's the only one that's been imaged at sufficient resolution for this comparison. Pallene, at least, we know is shaped like Methone, because of a crescent view that Cassini got. The rest we know little about. Keeping that in mind, here's a zoom in on the tiniest worlds in the upper left corner of my original comparison, finer-scale by a factor of 5. The ringfloof moons.

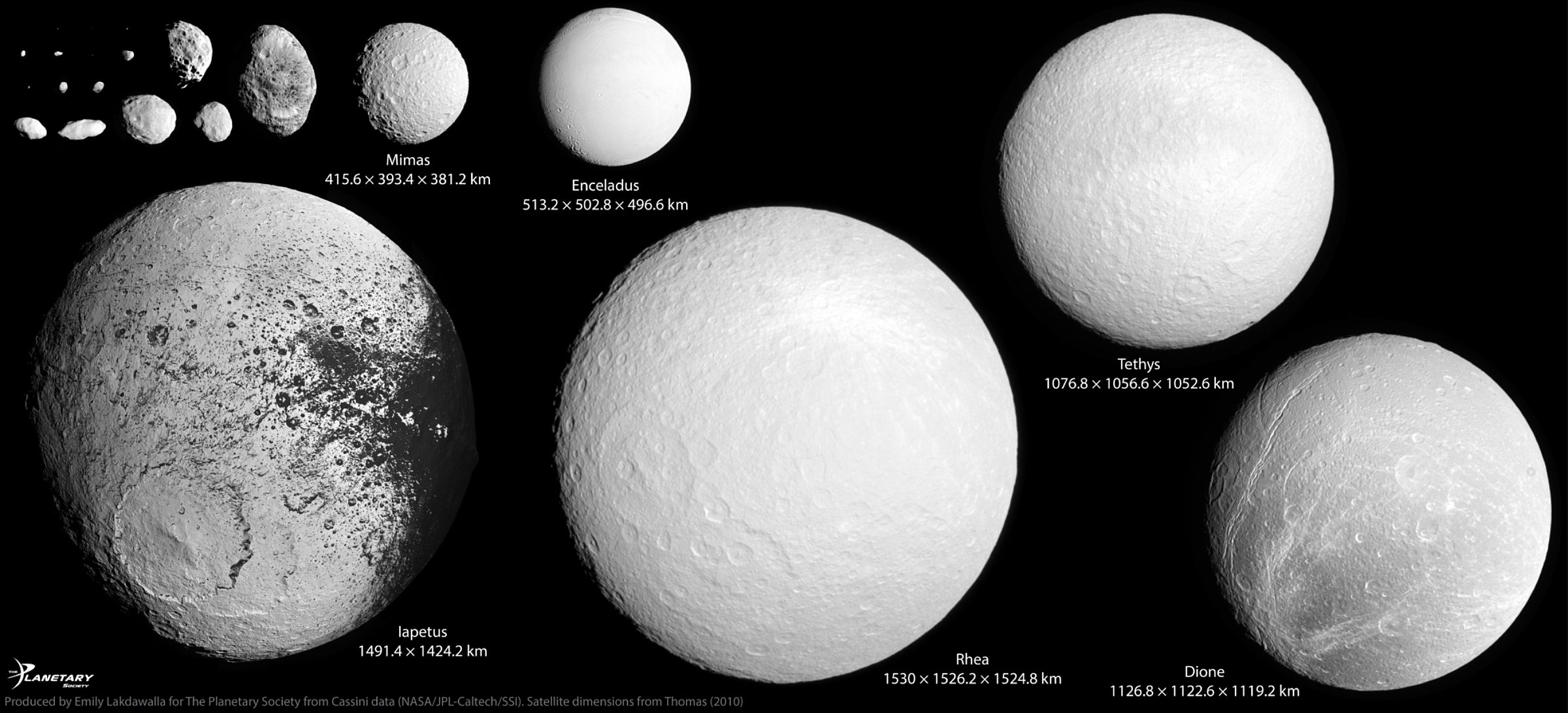

What's also striking to me about the original size comparison is how it doesn't in any way predict that the next-larger moons in the sequence would be quite round. Here's a final comparison, zooming out this time by a factor of 5, which brings in all of Saturn's major satellites except Titan (which would be as wide as this whole collage). This shape transition has to do with the competition between gravity and the strength of the icy material that Saturn's moons are made of. Ice is stronger than gravity until a moon gets just a bit bigger than Hyperion, and then all of a sudden, gravity wins and crushes the moons into round balls.

This was fun, and most of the work was with "old" Cassini data. I'll be having fun with this data set for the rest of my professional life.

P.S. If there are any scientists out there who need size comparison slides for public talks, hit me up!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth