A.J.S. Rayl • Jun 02, 2012

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Departs Winter Site for Field of Veins

May proved to be a merry, merry month on the Red Planet as Opportunity strolled out of her winter haven to continue the expedition around Endeavour Crater, and the Mars Exploration Rover (MER) mission roved on into yet another Martian spring. "Opportunity is on the road again," confirmed Steve Squyres, the principal investigator for rover science, of Cornell University during a recent interview with the MER Update.

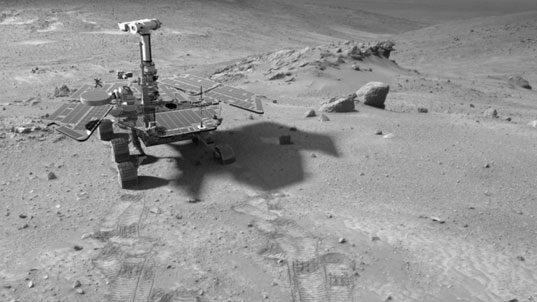

Mars Exploration Rover

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Maas Digital

"Incredibly on the road again," added Ray Arvidson, the deputy principal investor, from his office at Washington University St. Louis.

The rover's first drive since December 26, 2011 was a short, 3.67-meter (12-foot) jaunt off the 15-degree northern slope at Greeley Haven on May 8th, followed by several more drives heading north along Cape York on the rim of Endeavour Crater.

"Opportunity drove off the slope and left Greeley Haven, did a short couple of drives, and last weekend completed a 50-meter drive," elaborated John Callas, MER project manager, of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the NASA center where the MERs were designed and built.

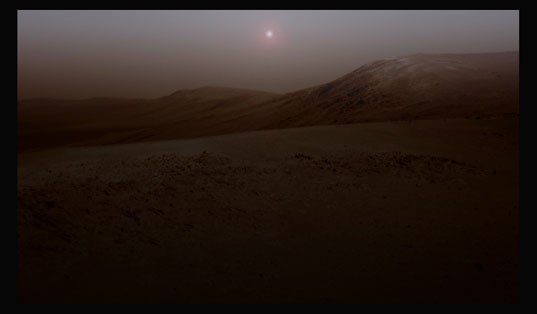

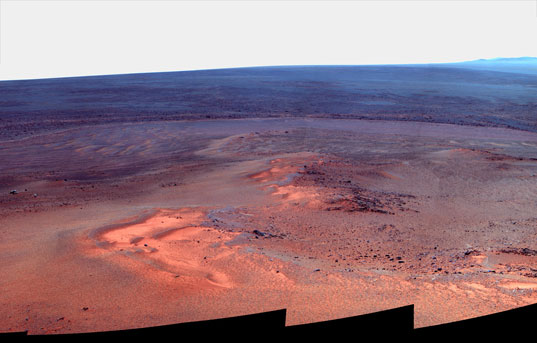

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell/ASU

Late afternoon at Greeley Haven

Opportunity catches its own late-afternoon shadow in this dramatically lit view eastward across Endeavour Crater on Mars. The rover used her panoramic camera (Pancam) between about 4:30 and 5:00 pm local Mars time to record the images taken through different filters and combined into this mosaic view. Most of the component images were taken on the rover's Sol 2888 (Mar. 9, 2012) during the low-solar-energy weeks of the Martian winter at Greeley Haven. In order to give the mosaic a rectangular aspect, small parts of the edges of the mosaic and sky were filled in with parts of an image acquired earlier from the same location as part of the 360-degree Greeley Panorama. The picture you're looking at here combines about a dozen images taken through Pancam filters centered on wavelengths of 753 nanometers (near infrared), 535 nanometers (green) and 432 nanometers (violet). It is presented in false color to make differences between materials easier to see. Note the dark sandy ripples and dunes on the crater's distant floor.Opportunity has been exploring the rim of the massive 22-kilometer (14-mile) crater called Endeavour since last August. The rover arrived at this much-anticipated destination on the 2681st Martian day, or sol, of its mission, after more than seven years and 33 kilometers of driving since landing in January 2004.

As energetic as Opportunity may be, she is getting on in rover years. For the first time ever, this rover had to park at a northerly angle for the mission's fifth Martian winter in order to soak up as much of the winter Sun as possible to be able work through the season.

Her twin, Spirit, wasn't so lucky. Located further south of the Martian equator and on the other side of Mars from Opportunity, Spirit had to park on a north-facing slope every Martian winter just to survive. Many team members believe Spirit's inability to get on such a slope during the fourth Martian winter was the reason she never phoned home after going into hibernation. Spirit's last communication was received on March 22, 2010.

This Martian winter, Opportunity's northern tilt may have been necessary, but it ensured the rover had enough power to work on a rich science campaign throughout the season, through winter solstice at the end of March, and even the days of the coldest temperatures a couple of weeks after that. Since then, winter has been slowly receding at Meridiani Planum and "spring is springing," as Scott Lever, one of the MER mission managers, put it.

During the last couple of months, Mars has been whipping up small gusts of wind that have been clearing some of the accumulated dust from Opportunity's solar arrays. The daily supply of solar energy began to steadily increase in April and that enabled the rover to drive off the sunward-tilted outcrop of Greeley Haven earlier than initially expected. "After months of being motionless, it was really good to be moving again," said Squyres, echoing the sentiments of every MER team member.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / M. Howard

Simulation of Opportunity at Greeley Haven

Michael Howard, the creator of the heralded Midnight Mars Browser software, put together this simulated image of Opportunity in her winter parked position at Greeley Haven, a few months back. This electronically simulated picture has served readers of the MER Update through the fifth Martian winter, because it "places" the rover – and vicariously the reader – in Greeley Haven offering a visual sense of the scene on Mars.As the Mars Odyssey orbiter relayed the data confirming Opportunity's completed first drive and it appeared in the rover mission control, the MER operations team offered up cheers and fist-pumped 'Yes's' with the news. Opportunity is eight and a half years into a 90 -day mission, after all. "There was definitely a really positive upbeat feel to the day," said rover driver Ashley Stroupe of JPL. "We were all excited and in a great mood. We had done a really detailed science campaign at the winter site, but we pretty much exhausted what we could do there. We were all anxious to be able to move on and there was a real air of excitement and happiness that day." "A lot of people came up to us and said: 'Hey I heard you guys drove,' and it was nice," agreed Lever. The team is feeling good and rightfully so. "We're glad to be out of the winter and back to what we were meant to do – which is drive," summed up Callas. "Opportunity is the rover that likes to rove."

Although scientific "gold" lies to the south, Opportunity is heading north, at least for a while to look for more gypsum-rich veins like Homestake. That little vein put the MER science team back in the news late last year, and again this month. Gypsum is "the best evidence yet" for water flowing on Mars, noted Arvidson, water that is less acidic than the rover has previously found evidence for – and more hospitable to the formation of life.

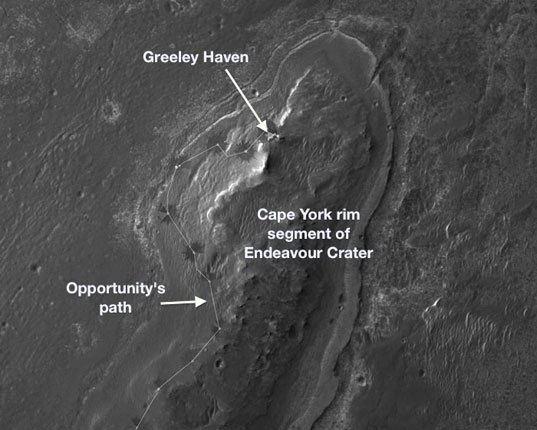

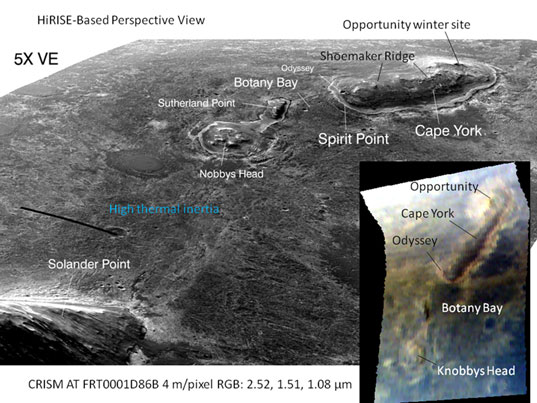

NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA

Cape York

Opportunity spent her fifth Martian winter working at Greeley Haven, labeled in this orbital image of the Cape York part of Endeavour Crater's western rim. This site features an outcrop with a north-facing slope of 15 degrees where the rover parked and angled her solar arrays toward the winter Sun and worked through the season. To the MER team's good fortune, the site presented geological targets of interest for investigating during the four- plus months of limited mobility while the rover was parked on the slope."If you look at the shape of Cape York, the long axis is northeast/southwest and it tilts inward toward Endeavour, because it's part of the rim," Arvidson explained. "So the north-facing slopes would be to the north of Greeley Haven, and that's where we've been driving."

And so May 2012 goes down in history as a month of continued exploration of Endeavour Crater, with Opportunity picking up the Endeavour expedition where she left off. "We're at a very exciting location at the moment – this swarm of veins," said Squyres. "We're looking for a vein that's fatter than Homestake, one that is wide enough to fill most or all of the APXS field of view. We'd also like one that we can use our rock abrasion tool (RAT) on so we can get below any surface dust or junk and down inside the thing," he added, not bothering to contain his excitement. "We're vein hunting right now." Once Opportunity roved away from Greeley Haven, the team had the rover pause to look back with her stereo, panoramic camera (Pancam) and in parting snap some multi-filter pictures of the surface targets it studied, and a few picture postcard landscapes of the place she called "home" for the last four and a half months.

Stuart Atkinson

Adiós Greeley Haven

On May 8, 2012, Opportunity drove for the first time since December 26, 2001, when she settled into a parked position for winter on a north-facing slope at Greeley Haven. In the ensuing sols, the rover would take several more drives before sprinting for 50 meters the weekend of May 25-26. Before that first long drive however, the rover paused and turned around to say "good-bye" to Greeley Haven and take a few shots. From the image components she sent down from her Pancam, Stuart Atkinson produced this richly colored picture of what she was taking in. You can see the rover's tracks toward the center, right side, of the image.For some on the team, it was a time for personal reflection as well, to remember Ron Greeley, the beloved planetary scientist, professor, mentor, and MER team member who passed away unexpectedly last October, in whose honor the winter site was named. During the winter, Opportunity snapped hundreds of pictures that are being processed now into the Greeley Panorama, the mission's next big 360-degree view of Mars. "We were able to collect a lot of good data over our so-called 'quiet' fifth winter on Mars – we weren't really hibernating at all!" noted Planetary Society President Jim Bell of Arizona State University, the lead scientist for Pancam.

"When all is said and done, the Greeley Pan will include 595 images acquired in five Pancam filters, and will be merged with a previous deck panorama that includes another 228 images in three Pancam filters," Bell added. "Right now the science team is busy analyzing and interpreting those measurements, as well as working with the rover planners to continue our exploration of Cape York."

Opportunity's winter science campaign was one of the richest, most successful winter science campaigns of the MER mission. "All planned observations and studies were completed successfully, and then some, and the analyses are in progress," summed up Arvidson, who oversaw the scheduling and the work.

The rover completed more than 60 radio Doppler passes while parked for the past 19 weeks, returning enough precise data about the Red Planet's rotation that will, once analyzed, improve our knowledge of Mars' core "by a factor of two," according the study's lead scientist, Bill Folkner, of JPL.

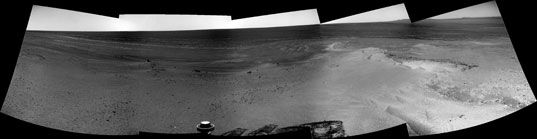

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

Greeley Pan glimpse

This mosaic of images taken in mid-January 2012 shows the windswept vista northward (left) to northeastward (right) from the location where Opportunity spent her fifth Martian winter, an outcrop the team calls Greeley Haven. The rover used her Pancam to take the component images as part of full-circle or 360-degree panorama. Hundreds of these component images are being assembled by the Pancam team into what will be forever known as the Greely Panorama. The view here includes sand ripples and other wind-sculpted features in the foreground and mid-field. The northern edge of the Cape York segment of the rim of Endeavour Crater forms an arc across the upper half of the scene.As part of the primary winter science campaign, Opportunity also used her Mössbauer, Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS) and microscopic imager (MI), instruments located on her instrument deployment device (IDD) or robotic arm to inspect more than a dozen targets within reach on the outcrop, completing "the first really detailed set of measurements of the Shoemaker Formation," Arvidson pointed out. In addition, the rover took lots and lots of pictures, some artistically reminiscent of Ansel Adams in their beauty, and also conducted routine assignments, including argon measurements from the atmosphere for a mission-long study on Mars' atmosphere.

After pulling out of Greeley Haven in early May, Opportunity made a brief stop a few meters north on Cape York at a bright-looking dust patch and launched into a brief campaign to look at and measure the chemistry of this "pure airfall dust deposit," as Bell put it.

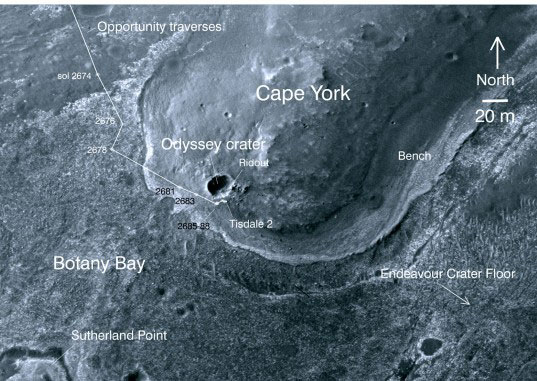

NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA

Cape York neighborhood

This image taken from orbit shows the path Opportunity drove in the weeks just after arrival at the rim of Endeavour Crater. The sol number (number of Martian days since the rover landed on Mars) are indicated along the route, with Sol 2674 corresponding to August 2, 2011 and Sol 2688 corresponds to August 16, 2011. The rover officially drove into the rim area of the crater at a place called Spirit Point, on its Sol 2681 (August 9, 2011). The base image of the map is a portion of a picture taken by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) instrument onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter on July 23, 2010."It is surprising to many people familiar with the mission that despite our years and years of exploring both Gusev and Meridiani, we have yet to fully characterize the ever-present and sometimes-annoying compositional properties of the famous Martian dust," Bell pointed out. "I'm hoping these recent measurements at North Pole, which we're only now starting to analyze in detail, will give us that new glimpse into the stuff that makes the Red Planet red!"

Most of the scientists however were focused on the Bench, an area or apron around the northern edge of Cape York filled with veins, the likes of Homestake. "The drive that happened last weekend put us right in the field of a bunch of veins, but they're small veins and there's still a lot of soil cover," noted Arvidson. "The objective since we left Greeley Haven is to get further to the north and northeast and closer to less soil cover on the bedrock and so that's the general plan right now."

Opportunity closed in on a longer vein earlier this week and there are plans for the rover to bump itself into a position this weekend to look at it up close, if the scientists decide it's worthy. "We are planning a small bump to try to get one of the veins into the IDD work volume," expounded Stroupe. "We're also going to take some color pictures of it. On Monday, we'll decide whether to go ahead and use the IDD or drive to another nearby one."

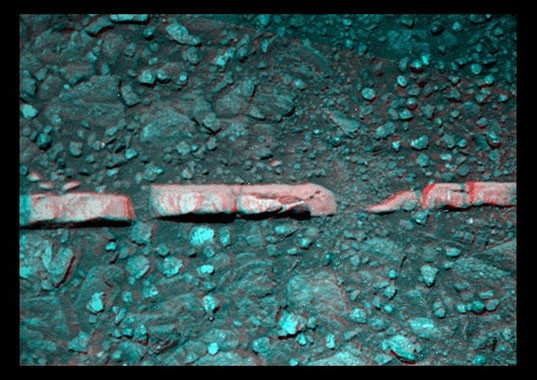

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / S. Atkinson

Homestake

Opportunity took this picture of Homestake, the striking vein running through bedrock, and Stuart Atkinson processed it here in rich color. "This is different than anything we've ever seen with either rover," MER PI Steve Squyres told the MER Update. On Dec. 7, 2011, at the American Geophysical Union fall meeting, he and Ray Arvidson announced Homestake is harboring gypsum. It was one of the biggest discoveries Opportunity has made. Gypsum is evidence for water flowing over the surface of Mars at a moderate temperature.Endeavour Crater offers Opportunity an almost ideal setting for scientific discovery, especially more than eight years into its original 90-day mission. The big crater was chosen in part because it is there of course, and because the rocks here record an ancient epoch in Martian history, much older than this rover has previously seen. More than 20 times wider than Victoria Crater, which the rover examined for two years (from August 2006 to September 2008), Endeavour was formed in Noachian materials that predate the sulfate-rich sedimentary rocks that the rover has explored for most of its mission.

In recent years, orbital data have indicated Endeavour's rim harbors phyllosilicates, ancient clay minerals in the form of smectite – evidence of ancient, wet environments with less acidity than the ancient environments found at sites this rover visited during its first seven years on Mars. Data from the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) – a visible-infrared spectrometer onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) designed to detect mineralogic indications of past water on Mars – indicates there are clay minerals to be found to the south, at the inboard side of Cape York, and farther south, at Cape Tribulation, where a mother lode of phyllosilicates appear to be just waiting for Opportunity.

Opportunity will soon be roving south for the clay minerals represent a kind of brass ring for the MER mission to groundtruth. "It'd be crazy not to look as we head that way, but the inboard side is not ideal in terms of power, so we've got to think it through," said Squyres. "We'll take what Mars gives us [there], but we think the best opportunities for finding the phyllosilicates are at Cape Tribulation," he added. "Remember, the point is not to confirm there are phyllosilicates there. We know there are phyllosilicates are there. You can think of the phyllosilicate signature as being a kind of mineralogical beacon that you can see from space that says: 'Go to this place. This is an interesting place.' The point is to see the place where the phyllosilicates are."

The solar energy remains something of an issue right now for Opportunity as far as long trips and tricky driving go. "But that's changing rapidly," noted Squyres. "The Sun is moving higher in the sky everyday. We can operate just fine in our current location. We'll operate there as long as we need to, to do the things we need to do, and then we'll move on when we can."

NASA / JPL-Caltech / JHUAPL

Geologic map of Endeavour's western rim

This map reveals the locations of where some of the geologic riches detected from orbital observations of Endeavour Crater. This crater is about 22 kilometers (14 miles) in diameter. As indicated by the scale bar of one kilometer (0.6 mile), this map covers only a small portion of the crater's western rim. A discontinuous ridge runs north-south, exposing basalt (coded blue) and clay minerals (coded green) believed to be from a time in Martian history before the deposition of sulfates on the portions of the Meridiani Plains region that Opportunity has seen during the rover's first seven years on Mars. This geological map is based on observations by the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) onboard MRO.Unless the Martian spring sends in a few more dust gusters to remove more of the accumulated dust from Opportunity's solar arrays so it can take in more sunlight, the rover will likely work in the field of veins for the next few weeks. "We'll head south as soon as power levels are adequate to handle the slopes where we'll go," said JPL's Diana Blaney, MER deputy project scientist, of JPL. There is little doubt that Opportunity will make it to one of the phylliosilicate-rich areas along Endeavour's rim, but positively identifying clay minerals will be something of a challenge, considering the rover's two specially designed mineral detectors are no longer working. "It will be harder without the Mössbauer and the Mini-TES, but there are things we'll see in the APXS data if there is a high enough concentration of phyllosilicates," assured Squyres.

True to form, Opportunity seems ready for just about any task. "She's doing great," said Stroupe. "Everything looks really healthy and good. We're very pleased. There doesn't seem to be any sign of any problem as a result of being parked for so long and the drives have been really good."

"Opportunity has been 'steady as she goes' so far," added Lever. "We were really pleased with all the data we got back after the first drive and the subsequent drives. We haven't seen anything strange and we're getting very close to business as usual." Still, spring has only begun to take hold at Meridiani Planum. "We're not at our peak energy-producing period of the summer, and there's still a fair amount of dust on the solar arrays – with a dust factor around 55%, they are 45% obscured," noted Callas, adding that there were a couple of slight dust gusters in May lifted a little more Martian powder from the rover's solar arrays. "There has been improvement. There have been small continual contributions to the improvement of the arrays. No big dust clearing events, but a bunch of little ones all adding together and all in the right direction."

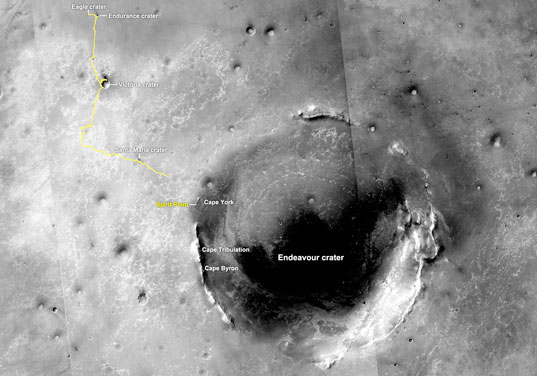

NASA / JPL-Caltech / MSSS

Opportunity's truly excellent road trip

The yellow line on this map traces where Opportunity landed inside Eagle Crater in January 2004 (at the upper left end of the track) to a point about 2.2 miles (3.5 kilometers) away from reaching the rim of Endeavour Crater or through the rover's Sol 2670 (July 29, 2011). In honor of Opportunity's rover twin, the team chose Spirit Point as the name for the site on Endeavour's rim targeted for Opportunity's arrival at the big crater. Spirit, which worked halfway around Mars from Opportunity for more than six years, ceased communication in March 2010. The base map is a mosaic of images from the Context Camera on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.The MER team takes nothing, least of all their rover, for granted. "You never know day to day," Callas pointed out. "This is Mars. The difference between winter and summer is often less than the difference between night and day for the rover."

By that, Callas means that Opportunity regularly sees 100 degrees Celsius change in temperature every single sol or Martian day. Imagine, going from -40 to +60 degrees, from specially lined mukluks to flip-flops in one day. Suffice to say: "We have to check everyday to make sure the rover is there," as Callas put it.

For now, Opportunity is roving and team is rocking. The best thing of all – for both the engineers and the scientists – is the technically complicated but emotionally simple act of exploration, pure and simple. "We're still learning and discovering things we've never seen before on Mars eight and a half years into this mission, and that is just so spectacular," said Stroupe.

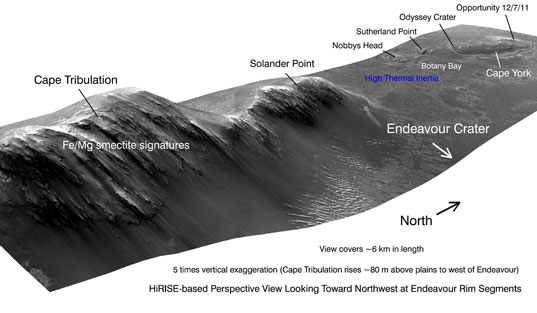

NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / JHUAPL

Opportunity's current roving grounds

This graphic combines a perspective view of the Botany Bay and Cape York areas of the rim of Endeavour Crater on Mars, and an inset with mapping-spectrometer data. Major features are labeled. In the perspective view, the landscape's vertical dimension is exaggerated five-fold compared with horizontal dimensions. Opportunity examined targets in the Cape York area during the second half of 2011. The perspective view was generated by producing an elevation map from a stereo pair of images from the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, then draping one of the HiRISE images over the elevation model.Meanwhile, down on Earth, Squyres, Arvidson, Bell, and others on the MER science team, reported on some of those "things never seen before on Mars," specifically Opportunity's findings since arriving at Endeavour. In a paper published in the journal Science on May 7th,1 they found that the outcrops of Shoemaker Ridge, from bedrock dubbed Chester Lake near the southern edge of the formation to various targets at Greeley Haven at the northern end, are "similar in physical appearance and elemental chemistry," and represent, they suggest, "the dominant surface rock type of Cape York," even though they are separated by more than half a kilometer.

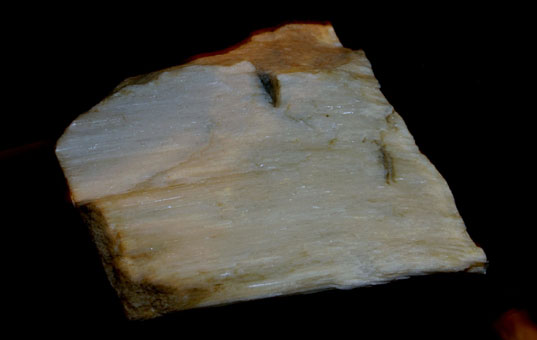

The dominant Shoemaker Formation rock type is "brecciated, with dark, relatively smooth angular clasts up to around 10 centimeters in size embedded in a brighter, fractured, fine-grained matrix . . . formed during the Endeavour impact . . . [and texturally] similar to the typical texture of suevite breccias common in impact settings on Earth and the Moon," as they described in the article.

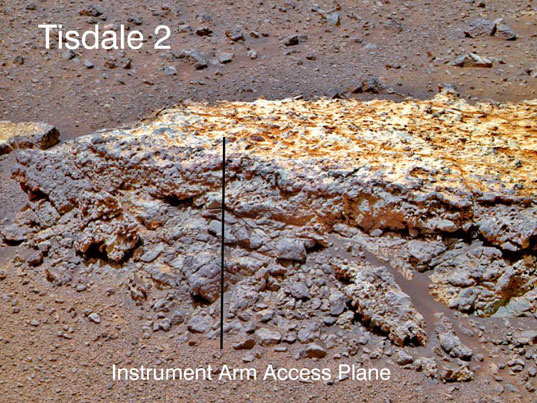

One ejecta block, Tisdale, which Opportunity found near a smaller Odyssey Crater at the southern end of Shoemaker Ridge, differs texturally and compositionally, and features far more zinc than all other sample analyses to date from Mars. It "may represent a deeper unit within the Shoemaker formation," the scientists wrote.

They further concluded that Tisdale is similar to what Spirit found in hydrothermally altered rocks around Home Plate in Gusev Crater, and could be "the main breccia unit of the rim," while Chester Lake and the rocks near Greeley Haven were likely emplaced later in the impact flow. "The heating caused by an impact the size of Endeavour is sufficient to cause hydrothermal circulation if water is present," they wrote, suggesting that the enrichment of zinc in Tisdale "could have resulted from such activity."

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

Tisdale

This close-up of Tisdale2, the first rock Opportunity examined in detail on the rim of Endeavour crater, has textures and composition unlike any rock the rover has ever examined. Its characteristics are consistent with the rock being a breccia, a type of rock in which broken fragments of older rocks are fused together. Tisdale2 is about 30 centimeters (12 inches) tall.A gently outward-sloping topographic bench, around 6 to 20 meters wide surrounds Cape York, now known among rover followers as simply the Bench.

"The outer part of the bench on the western side exposes bright, thinly bedded sandstones with bedding that dips shallowly toward the plains," they wrote in the Science article. "These sandstones lie directly above darker granular sedimentary rocks that form the inner portion of the bench . . . The inner bench materials, in turn, overlie the Noachian breccias that form the lower slopes of Cape York."

The Bench is distinguished in many places by "bright linear veins," as the scientists described. Opportunity quickly examined one of them, Homestake, just before settling in for the winter. "A discontinuous, flat-topped ridge 1 to 1.5 cm wide and around 50 centimeters long, this vein "stands up to around 1 centimeter above the surrounding bedrock, which suggests that it is more erosion-resistant than the material into which it was emplaced," according to the authors. The scientists further found that "the orientations of the veins" suggest that the rocks of the Bench surrounding Cape York "were subjected to horizontal tension perpendicular to the bench margins at the time of vein emplacement, perhaps related to sediment compaction, dewatering, and settling."

Unlike the Burns formation sulfates, which are rich in jarosite and dominate the Meridiani plains, "the gypsum of Homestake did not require acidic fluids for its formation," the scientists found. They did note and suggest, however, that the water and/or "fluids from which the gypsum was precipitated may have been a contributor to the overall hydrologic budget" or environments "responsible for formation of the Meridiani sulfate sandstones."

In summation, the authors wrote: "The ubiquity of impact breccia at Cape York contrasts with the only other Noachian terrain explored in situ, the Columbia Hills in Gusev Crater. The rover Spirit encountered great lithologic diversity there, including materials interpreted as impact ejecta. However, none were breccias, and none had the lateral extent of the Shoemaker formation." The scientists concluded and suggest that "the difference can be attributed to Opportunity’s sampling of the rim deposits of a single large crater, rather than Spirit’s sampling of more distal ejecta from multiple impacts."

NASA / JPL-Caltech; Rover model by Dan Maas; synthetic image by Koji Kuramura, Zareh Gorjian, Mike Stetson and Eric M. De Jong

Spirit on the flank of Husband Hill

Spirit spent her first winter on north-facing slopes on Husband Hill. This image was created from a computer simulation of the rover that was then dropped into a Pancam panorama that the rover took on the flank of Husband Hill on her Sol 454 (April 13, 2005).Homestake provides "clear evidence" for "relatively dilute" water "at a moderate temperature," perhaps supporting locally and transiently habitable environments. "More broadly, rocks at Cape York appear to record early events in a transition from (commonly) hydrothermal waters that altered basaltic crust to phyllosilicates to sulfate-charged ground waters that generated salt-rich sandstones deposited widely over the Meridiani plains and elsewhere," they wrote.

"The main punch line is this: the gypsum vein is unequivocal evidence of water running through fractures and filling in with this soluble gypsum," summed up Arvidson. "It is the most direct evidence we've had ever for an extensive amount of groundwater."

"The nice thing about exploration is that when it goes well, afterwards, it always look like you knew what you were doing," mused Squyres. "At the time, it's a different story. But this paper almost wrote itself. It was all just there."

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

When May dawned at Meridiani Planum, Opportunity was still parked on a slope at Greeley Haven on the north end of Cape York on the rim of Endeavour Crater with an approximate 15-degree northerly tilt.

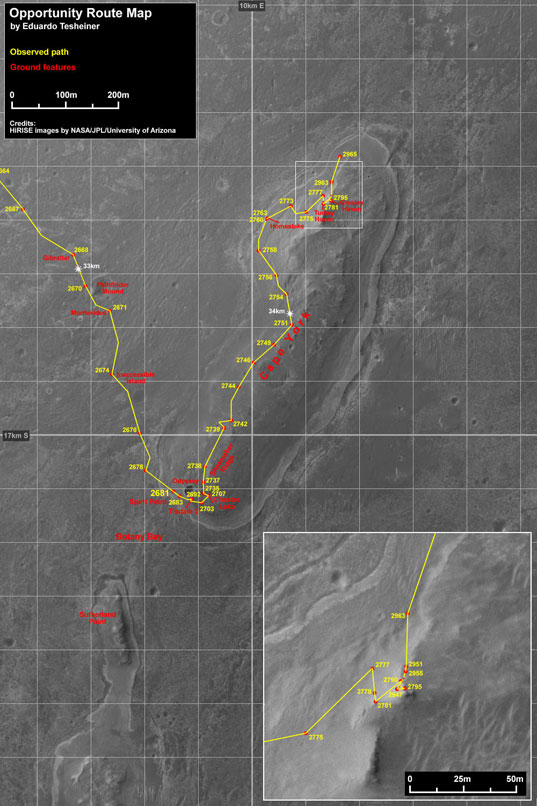

NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / MSSS / E. Tesheiner

Opportunity route map

This route map shows Opportunity's travels up to its Sol 2965 (May 27, 2011) and its approximate current location at the northern end of at Cape York. It was produced by Eduardo Tesheiner, of UnmannedSpaceflight.com, who created it from images taken by cameras onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. The rover, which officially reached the rim of Endeavour Crater rim on Aug. 9, 2011, settled into a parked position on a north-facing slope last Dec. 26, 011 for its fifth Martian winter. After four and a half months of working from a solitary position, the rover wrapped up her science campaign at Greeley Haven this month and roved on.Although spring had yet to engulf Endeavour with sunshine, the rover was producing around 365 watt-hours of power; good enough, it seemed for driving and the latest predictions were green-lighting that notion. "We were excited when we saw the energy levels could support driving again," said Callas, who had hinted last month that Opportunity would be roving on in early May.

With an atmospheric opacity registering a slightly hazy Tau of 0.480 and an improving solar array dust factor of 0.534, the team made its decision: it was time for their rover to put the bow on the winter science campaign and move along.

On Sol 2940 (May 1, 2012), Opportunity conducted one of the last radio Doppler tracking passes for the geo-dynamic investigation into Mars' core, a study designed really for a lander, as reported in previous MER Updates. Nevertheless, parked as she was, Opportunity stepped up to the challenge and sent home textbook altering data from 60 radio Doppler tracking passes conducted during the winter that will serve to knock out half of the models of Mars’ interior currently in play, refining and improving our knowledge about the planet's core "by a factor if two," according to the study's chief scientist, Bill Folkner, of JPL.

"The data through the end of April meet our expectations," Folkner told the MER Update. "We are finding that calculating the effect due to the motion of the high-gain antenna more complicated than we expected, but are confident that we have enough information in hand to meet our needs." It may still take some time and iteration "to get the right results," he continued. "We could probably have one done already, but we have been busy with GRAIL and MSL the last months or so, and have to prepare something for Juno by end of May, so won't be working full bore on [Opportunity's] data set right away."

Although the Greeley Panorama was completed, Opportunity had to devote quality time during the first week of May attending to wrapping up the Microscopic Imager (MI) picture campaign, an assignment that has produced a collection of detailed mosaics of the Shoemaker Formation bedrock on which she was parked, and finishing up the Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS) measurements of the extended bedrock region around the surface rock target the team calls Amboy.

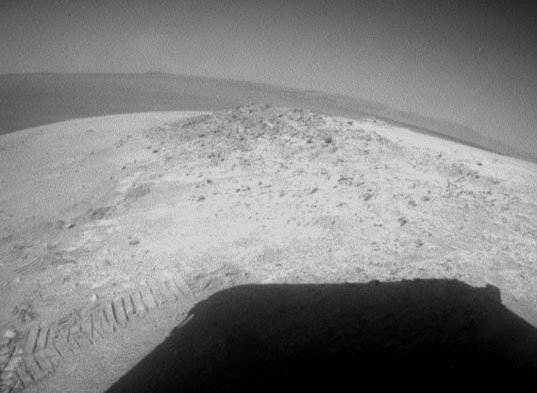

NASA/JPL-Caltech

Looking Back at Greeley Haven

Opportunity drove about 12 feet (3.67 meters) on May 8, 2012, after spending 19 weeks working parked at Greeley Haven while solar power was too low for driving during the Martian winter. The winter worksite was on the north slope of Greeley Haven. The rover used its rear hazard-avoidance camera capturing this view looking back at the Greeley Haven as it completed the May 8th drive. The dark shape in the foreground is the shadow of Opportunity's solar array. The view is toward the southeast.The continued improvement in the solar insolation, or the amount of solar radiation energy hitting the surface at Meridiani Planum, and the flurry of recent, albeit modest, dust cleaning events on the rover's solar arrays brightened the prospects for driving and neither rover nor team members could sit still much longer. Everyone was chomping at the bit to get back on the road.

As the second week of May got underway at Meridiani Planum, the MER team issued their directive and on Sol 2947 (May 8, 2012) Opportunity drove off Greeley Haven heading north.

Opportunity's first post-winter drive pushed the rover's odometer – which had for more than four months been "frozen" at 34.361.37 meters (34.36 kilometers or 21.35 miles) – by just 3.7 meters (12 feet). Even so, it took her back to more or less on level terrain, and as a result and as expected, her northerly tilt decreased from around 15 degrees down to about 8 degrees. And that in turn caused the rover's energy to drop to 357 watt-hours. Still with the atmospheric opacity or Tau hovering around 0.476 and the solar array dust factor at 0.526, the rover was okay energy-wise.

After being stationary for 130 sols during the winter, Opportunity was back to driving. Perhaps the best news of the drive was that all six of the rover's wheels, including the problematic, "hot" right-front wheel, drew nominal or normal currents from their respective motors.

"By the time Opportunity drove, we were already pretty relieved," said Lever. "For us on the team, our concerns were with the deepest part of winter, getting past Winter Solstice and then the month or so after that, where the coldest temperatures and the lowest solar power came within a couple weeks of each other. So in many ways, we already had our big excitement. But from other people outside, there was a lot of positive reinforcement from folks saying, 'Awesome, you guys are driving again.' It is good to be moving on."

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell

North Pole, Meridiani Planum

Opportunity took this true color picture of ripples she passed after leaving Greeley Haven this month, one of which contained the pristine dust patch with a target dubbed North Pole. The rover spent time taking a close-up look at a target in one ripple the team christened North Pole. Planetary Society President Jim Bell is one of the scientists interested in finding out whether or not this pristine patch of dust has anything to tell us about "why the Red Planet is red."Opportunity first drove to a nearby dust patch, located on a classic Meridiani ripple, to investigate the nature and origin of rusty red Martian target. A series of short drives during the second week and into the third week of May, roving on Sols 2949, 2951, 2953 and 2955 (May 10, 12, 14 and 17, 2012), for a total of just more than 46 feet (13.9 meters), put her in position to study the pristine patch.

Dust covers much of Mars and this patch was an opportunity for Opportunity to look into the origin of the dust by way of its chemical signature. The science team decided to have the rover use her IDD instruments to look at it up close, on a chosen target dubbed North Pole. "We were driving by this bright red part of a ripple, and it was bright and red enough that we stopped and put the APXS on it, and did MIs, both the undisturbed surface and also the track that we drove through," confirmed Arvidson. Turns out, North Pole is "very much like a dusty patch we measured early in the mission, named Les Houches named for a place in France," he added.

On Sol 2957 (May 19, 2012), Opportunity took a series of MI pictures for a mosaic of the surface target called North Pole on the dust patch, and then placed her APXS for a multi-sol integration. The rover continued her investigation, repositioning her instruments on an associated target for another set of MI pictures followed by another set of APXS measurements on Sol 2960 (May 22, 2012).

MER scientists are only beginning to analyze the recent measurements at North Pole, however, and some scientists, including Bell, are hoping to find "a new glimpse" into what makes Mars red.

What they know so far is that the dust patch is "enriched in sulfur compared to the basalt sands," according to Arvidson. "So it's another dust end member where the interior of the ripple is basically basaltic sand, and it's another piece of the puzzle, another area where dust collects on the surfaces of ripples until it's blown off. There's nothing here that's Mars shattering. But it is more information to work with," he offered.

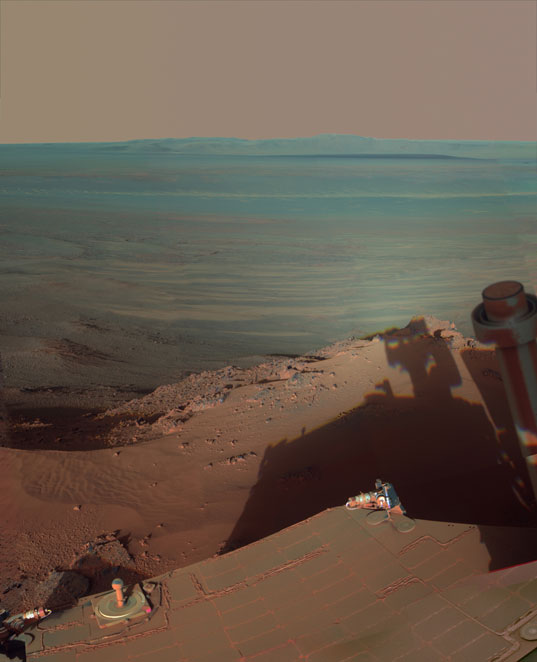

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell/Eduardo Tesheiner

Veins everywhere

During the weekend of May 25-26, 2012, Opportunity made a 50-meter drive that put her before a field of veins. Many of these veins appear to be much like Homestake, which the rover checked out last December before the Martian winter set in. Stuart Atkinson created this mosaic from the component images the rover sent home earlier this week. It shows the rover's view ahead.During the third week of the merry month of May, Opportunity benefited from another small dust guster that boosted her solar array energy production to 395 watt-hours. The skies above continued to clear, with atmospheric opacity or Tau registering less 0.387. And the rover's solar array dust factor continued to creep up to 0.559. It was all adding up "in the right direction," as Callas put it, and during May the rover was also able to revert to solar array wake-ups, the autonomous rover wake-ups induced by bright morning sunlight.

At this point, the plan ahead remains the same as announced in last month's MER Update: to resume driving toward the north end of Cape York in search of more gypsum veins and then head to the inboard side of Cape York to seek out the phyllosilicates detected from CRISM onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

"The idea is still to go north into the Bench that surrounds Cape York, because the Bench, we think, based on the Science paper [as cited in this report], is the oldest sedimentary unit surrounding the Noachian Cape York rim," explained Arvidson.

"There are two hanging issues we have to deal with," Arvidson continued. "One is the gypsum veins, one of which we looked at before winter. Homestake didn't fill the field of view of the APXS. It was too narrow and too narrow to RAT any surface coatings off of – and we didn't have a lot of time to spend there," he reminded.

"Then, the bedrock next to Homestake – called Deadwood – we didn't have time to RAT that," Arvidson added. "The APXS measurements suggested a lot of local material from Cape York was incorporated into the measurement. We didn't know at the time if it was dirt on top of the rock or dirt embedded in the rock, and it's important to know the environment of deposition. If it's the first sulfate unit to form with rising groundwater, you might expect a lot of local debris to come off of Cape York. Or maybe it's like the other sulfate-rich sands and we have a lot of contamination by a lot of soil on Deadwood."

Last weekend, Opportunity put the pedal to the metal and drove for 50 meters, pushing her odometer to 34,456.53 meters (34.45 kilometers or 21.4 miles). "It was really nice to do a long drive again," said Stroupe. "We have a minimum limit on our northerly tilt to make sure our power stays good and we expected that to trip somewhere and it did."

The rover was automatically brought to a halt when the northerly tilt dipped to 2.5 degrees, according to Lever. But as Opportunity's luck would have it, the fault trip left her at the edge of "a beautiful field of veins," as Stroupe defined it, veins the scientists assume are made-up of gypsum, like Homestake.

The gypsum found in Homestake is, as Arvidson put it simply, "the best hard evidence for water flowing through fractures on Mars."

"We're very interested to find out in exquisite detail what this stuff is made of," added Squyres. "We did the best we could with what Mars gave us at Homestake, but Homestake is narrow, the width of your thumb, and it was sticking up above the ground so we couldn't RAT it. Obviously, it's calcium sulfate and a lot of evidence it's gypsum. But what else is in there? What's the purity? We don't have a good handle on that yet. We have some pretty good guesses, but we want some hard data that absolutely nails down what the composition is."

On a short, 11-meter (36.08-foot) jaunt earlier this week, Opportunity's Sol 2967, the rover moved in on a vein that is about 2 meters in length, to see if it's the one to dig into. "A lot of them are not worth doing IDD work on, because they are not even as nice as Homestake," Arvidson said. "This one looks skinny to me, and so we'll probably just do Pancam imaging of it, and then do a lot of Pancam imaging of the surroundings to search out north-facing slopes with more veins," he added.

While there is no doubt that Opportunity is there to help the scientists figure out the story of the veins, the excitement is somewhat tempered. "We're driving through the vein network looking for a juicy one, but so far we haven't seen a thicker vein," said Lever.

The plan to be sent to the rover on June 1st for the June 1-3 weekend activities includes commands for Opportunity to rove again, but it looks like it won't be much of a drive. "We are planning a small bump to try to get one of the veins into the IDD work volume," confirmed Stroupe. "We're also going to take some color [Pancam] imaging of it. On Monday, we'll decide whether to go ahead and use the IDD there or drive to another nearby vein."

Opportunity is now in a period of "restricted sols," where communications take longer and workflow is somewhat reduced, so she may be on the hunt for just the right vein for a while. The good news is that the rover is "seeing veins all over the place right now," said Callas.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / OSU

Western rim of Endeavour

This orbital illustration shows portions of the western rim of Endeavour Crater on Mars from a perspective looking toward the northwest. The image exaggerates the landscape's vertical dimension five-fold compared with horizontal dimensions. The scene covers about 6 kilometers (4 miles) in length. Major portions of the rim are labeled. Generated by producing an elevation map from a stereo pair of images from the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, the image wizards then draped one of the HiRISE images over the elevation model. Elevation data were calculated by researchers at Ohio State University, Columbus.Although Opportunity is still energy-constrained and limited in terms of what kinds of slopes she can perch on, "in its current location, the rover can operate just fine," Squyres pointed out.

Once Opportunity does find a suitable vein for an in-depth study, the scientists will want to do all the in situ measurements they can, according to both Squyres and Arvidson, including using the rock abrasion tool (RAT), and taking comparison measurements and images of the surrounding bedrock. That will take some time; a few weeks, likely.

The rover drivers are good with that. For starters, there's no rush. The clay minerals or smectite on the inboard side of Cape York – the next scientific objective – are on slopes that have a southerly tilt to them, reminded Callas. "Right now we don't want the rover to see more than about 5 degrees of southerly tilt for power reasons," he said.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / S. Atkinson

Triple crunch

After checking out the vein dubbed Homestake in December 2011, Opportunity was instructed to perform a "triple crunch," as Deputy PI Ray Arvidson called it. "We backed over the vein, drove forward, then turned in place and left. We crunched it," he said. It turned out to be filled with "sparkly bits." Stuart Atkinson processed the image here in "retina burning false color." What a mess, but what a mix of stuff.Plus, the vein hunt gives Opportunity the chance – not that she needs it – to get her wheels warmed up and wanderlust in gear. "She is in a very target rich area, so we're going to explore a little bit with some short drives, looking at a bunch of these veins before moving on," said Stroupe.

Squyres, as usual, declined to predict when exactly Opportunity will head south to the inboard side of Cape York, and of course so much depends on Mars and the rover herself. But the field of veins is not all that big, and in a few weeks time, spring will be in full "bloom" in the southern hemisphere of Mars.

"The Sun will be high enough then so that we can go around Cape York clockwise on the Bench to the inboard side of Cape York where geologically we expect the clay minerals to be," said Arvidson.

Opportunity, for her part, seems ready for whatever her teammates want her to do. "The rover is doing very well," said Lever. "The wheel motor currents are all within range, even the right front which has been slightly elevated – no problems. We expect to possibly get down to a northerly tilt of between 0 and 1 degree on drives coming up, so we are safe to drive at level terrain. In fact, our power engineer just declared today that there is no problem in going down to -5 northerly tilt in the current environment, so we're definitely on the road again. That gives us a lot more leeway to look at a lot more stuff."

The magic number the MER engineers are looking for is -15 northerly tilt. "That will allow us to cruise around to the Endeavour side of Cape York, where we expect to begin the search for phyllosilicates," Lever said. It's actually kind of perfect timing here. We're getting this natural transition to a thicker gypsum vein, and once we've characterized this local area and completed the gypsum IDD work, we will then move on to look for the phyllosilicates on the crater side of Cape York."

The rover planners will be carefully calculating Opportunity's paths to that "beacon" of phyllosilicates. "It's the obvious thing to do, the part of Cape York we haven't seen yet," said Squyres. "But the strongest phyllosilicate signature is not at Cape York. It's farther south, which is why we want to head south. Ultimately, we want to work our way south because we want to get across Botany Bay and up towards Cape Tribulation."

As June begins, Opportunity roves on into the Martian sunsets and wakes up with the morning Sun, taking each sol as it comes. "Everything that is working is working," said Arvidson. "I do think we'll get to the inboard deposits before Curiosity gets to the valley that holds the iron magnesium smectites. The issue is that Mössbauer isn't working and Mini-TES doesn't work. Those are the two instruments that directly detect minerals. So we have Pancam, which can detect the iron phases, and we have APXS, which detects elemental abundances, and we have imaging that can provide context. We're going to have to work triple overtime to figure out which place to target at the inboard side of Cape York, and what measurements to do and how to tell whether or not we've actually seen clay minerals."

There isn't a MER team member, neither scientist nor engineer nor rover, who has ever shied from putting in the work and the time it takes to uncover Mars' secrets and make the kind of discoveries that change the way we Earthlings think about our favored planetary neighbor. This team earned its legendary status in large part because of its integrity and its attitude. Bring it on.

With the promise of continued scientific discoveries at Endeavour Crater and the arrival in early August of the MERs’ descendant, Curiosity, it is looking to be quite a summer both on Mars and on Earth.

Groundtruthing the presence of phyllosilicates is obviously important, Squyres agreed. "But it's not like – 'Oh we found phyllosilicates!' We know the phyllosilicates are there anyway. It'd be cool if we could say, 'Yep, this is a phyllosilicate signature.' And if there's enough we'll be able to see with APXS, because there are these excess light elements that you can detect their presence. But that's not the point," he stressed.

"That's not the exciting thing. There's no doubt the phyllosilicates are there. I want to know why they're there," Squyres sad. "I want to know how they got there."

Stay tuned.

Citations

1. S.W. Squyres, R.E. Arvidson, J.F. Bell III, F. Calef III, B.C. Clark, B.A. Cohen, L.A. Crumpler, P.A. de Souza Jr., W.H. Farrand, R. Gellert, J. Grant, K.E. Herkenhoff, J.A. Hurowitz, J.R. Johnson, B.L. Jolliff, A.H. Knoll, R. Li, S.M. McLennan, D.W. Ming, D.W. Mittlefehldt, T.J. Parker, G. Paulsen, M.S. Rice, S.W. Ruff, C. Schröder, A.S. Yen, and K. Zacny, "Ancient Impact and Aqueous Processes at Endeavour Crater, Mars," Science, 570 336, May 7, 2012.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth