A.J.S. Rayl • May 31, 2011

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Spirit Mission Declared Over, Opportunity Roves Closer to Endeavour

The Mars Exploration mission suffered the loss of Spirit and shifted to one-rover operations in May, but Opportunity carried on, blasting across the plains of Meridiani to within 2 miles (3.5 kilometers) of its next major destination and discovery.

At Gusev Crater, sounds of silence greeted the last of more than 1300 commands beamed to Spirit through the Deep Space Network X-band, and the ultra-high frequency (UHF) relay communications systems with Mars Odyssey and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, each an attempt to elicit a response from the rover.

Spirit presumably, as programmed, went into a hibernation mode after a final electronic communiqué March 22, 2010 during its fourth Martian winter. The team hoped to hear from the rover by early this year, once it had a chance to re-charge its solar-powered batteries. But going into the 14th straight month of silence and not so much as a ‘beep’ through all the efforts, the consensus at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the NASA center where the rovers were designed and built and are being managed, shifted for good. Spirit is not going to be phoning home.

On Monday, May 23rd NASA and JPL officials decided to conclude the official recovery effort with the last of the sequences prepared for the intensified strategy, scheduled to be sent early May 25, 2011 Pacific Time. Despite plans for a televised press event at NASA headquarters this week to announce Spirit's decommissioning, the official announcement of the end came abruptly, before those last signals were sent, in an impromptu press teleconference on May 24th.

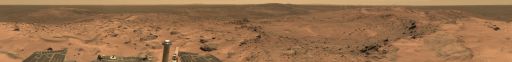

Spirit: still shining

Spirit: still shiningIn this image taken on Mar. 31, 2011 by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and colorized and turned into art by Stuart Atkinson, Spirit seems to shine in the Sun. It's a fitting, final salute from a star of space and screen. [Spirit is the tiny white spot to the left of the circular formation in the left portion of the image.] Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / colorized by S. Atkinson

Technically, there is no “off” switch on the MERs, so, Spirit, if it's 'alive,' could still respond. NASA actually will reach out again for the rover. There are pre-sequenced UHF relay passes onboard Odyssey and those will continue through June 8, 2011. It’s also likely that operators at NASA's Deep Space Network (DSN) will listen and/or reach out again, time permitting, between now and the end of the year. But even if Spirit responds, there won't be much time for it to do much of anything, if anything, before the next winter grips the southern hemisphere of Mars and delivers the final blow. Regardless of how unceremoniously the rover was sent-off, the Spirit mission is over.

The MER team members are moving on. "We've had a long time to get used to the notion," said Steve Squyres, the principal investigator for rover science and Cornell University professor, who was actually in Japan on other NASA business when the mission's end was announced. "We lost contact with Spirit better than a year ago. We've been trying everything we can, but the prospects of regaining contact with the vehicle have been diminishing gradually and steadily with time." Ray Arvidson, the MER deputy principal science investigator and geology professor at Washington University St. Louis, agreed: "This has been going on for a while."

Still, there is grieving. Spirit was, after all, a team member, the robot field geologist that was up there on Mars doing the work, doing our bidding in exploring the brutally cold, dusty, desolate planet with which we Earthlings have forever had a love affair. "I see near tears in the hallways here at JPL, and reddening of faces when I talk with certain people," said John Callas, MER project manager. “Spirit struggled so much. I think all our emotions were closer to Spirit, because Opportunity didn't need our emotional support like Spirit did."

"She was a tough little rover that earned our respect," said Bill Nelson, chief of the MER engineering team.

"Every day, for more than seven years, we have come to work on Mars and we have come to feel very deeply for these rovers," said Squyres. “This sadness is expected."

What seems to have surprised team members more than anything is how good they feel in spite of their grief. "When you look at everything that rover has accomplished, the sadness is tempered to a large degree by a significant measurement of pride and sense of accomplishment," Squyres reflected earlier today. “Spirit is dead, but boy she died an honorable death."

Designed, built, and tested together, Spirit and Opportunity were brought to “life” with a little help from some 4000 people and dozens of companies, in less than four years, on a budget of $820 million, a near-miracle level achievement in and of itself. They were "warrantied" for a 90-day mission with the capability of driving one-kilometer around their respective landing sites, and named in a contest co-sponsored by The Planetary Society. Despite a string of mishaps, upsets, last minute emergencies and near catastrophes, they managed to launch from Cape Canaveral on time, three weeks apart, into picture perfect skies in the summer of 2003.

Spirit lifted off first and would land first, on January 3, 2004 in Gusev Crater. The size of Connecticut, Gusev Crater is a more rugged, dustier terrain, located on the other side of Mars and a little farther south of the equator from the more temperate locale where twin Opportunity would land three weeks later.

Since scientists knew the Martian winters in Gusev are colder and darker and considering that the rovers could not tilt their solar arrays, no one really expected Spirit to survive for long, maybe “at the very best, a year,” offered Jake Matijevic, a member of the original design team and former chief of rover engineering – if, that is, they could get the rover parked on a northern facing slope for the winter where it could position itself so the solar arrays faced the Sun.

Spirit launches

Spirit launchesMars Exploration Rover Spirit took off for Mars on June 10, 2003. Despite being 'zapped' en route by the then-largest solar flare on record, the rover arrived and landed on Mars right on time at 8:35 p.m., Jan. 3, 2004 Pacific Standard Time.

Credit: NASA

Whatever assumptions and bets may have been made on her life, this robot field geologist had other plans and seemed almost hellbent on teaching the team to never say 'never.'

Spirit found that northern slope, two kilometers away, on Husband Hill, survived her first Martian winter, and then managed to survive two more Martian winters, living long and prospering against the odds. As she maneuvered and picked her way through the rocky landscape, up Martian hill, through Martian dale, and around ancient volcanic formations in Gusev’s inner basin, she earned distinction after distinction for the mission …the first to hike a hill on another planet … the first to take a picture of Earth from another planet … the first to take pictures of Mars’ notorious dust devils from the surface … the first to find near pure silica … and the first to find carbonates in rocks on Mars, a certain sign of near-neutral water that could have provided a suitable habitat for the emergence of life – exactly what the MERs had been sent to find.

The rover put a total of 7,730.50 meters (4.80 miles) on her odometer, sent home more than 124,000 images from the surface along the way, and worked for more than six Earth years (and three Mars years). Perhaps most importantly, as Callas has often pointed out: "Spirit sent Mars home, into our offices and dens and living rooms, and made Mars familiar.”

None of it came easy for Spirit, in large part because of the terrain. This rover had to struggle to make discoveries, while her twin was all but handed the mission objective of finding evidence of past water on a gold platter. Through it all, Spirit persevered, though she wasn't always happy about it. She threw enough electronic fits and tantrums to garner a reputation as a drama queen. But in her robot heart of hearts, the rover was a trooper’s trooper from the beginning, dedicated and determined, always forging onward in ever-resilient ways to complete her tasks, sometimes in the most seemingly courageous of ways.

When her right front wheel stopped working in 2006 during something of a mad dash to get to a winter haven, for example, Spirit turned around and started driving backward with five wheels, dragging her broken front wheel like an anchor, pulling into her destination, in the nick of time. “How can you not love this rover?” asks rover driver Scott Maxwell almost every time he tells that story.

Simulation of Spirit in the Columbia Hills

Simulation of Spirit in the Columbia HillsTo create this image, a computer simulation of Spirit was dropped into a Navcam panorama captured on Spirit's sol 438, as it was climbing into the Columbia Hills. SourceCredit: NASA / JPL-Caltech; Rover model by Dan Maas; synthetic image by Koji Kuramura, Zareh Gorjian, Mike Stetson and Eric M. De Jong

Even Mars seemed resigned to agree. In dragging that bad wheel, around Home Plate, Spirit left a trail of trench – and in that trench made one the mission’s grandest discoveries – near pure silica near Home Plate, a finding that led to others and bolstered the leading hypothesis that this circular plateau is actually an eroded over fumarole or vent in the Earth's surface from which steam and volcanic gases were emitted eons ago. An ancient environment all but came alive in the data … active, erupting volcanoes, steaming hot springs, and spewing fumaroles, conditions in which life, however exotic and small, could have existed.

In April 2009, as Spirit was driving around Home Plate to its next destinations to the south, an unusual mound and a concave depression, its left wheels broke through a crusty surface layer and sunk into a sandy mix of soils. The MER team spent the summer researching, analyzing and testing with ground rovers in the Mars yard at JPL.

Finally, in November 2009, several strategies prepared, engineers began commanding Spirit to begin her extrication. When the first exit forward-drive strategy failed, they initiated a backward-drive strategy. The rover began making progress, just as NASA officials announced it was being reassigned to lander status in January 2010.

In a matter of a couple of weeks, although Spirit had moved an impressive 13 good inches toward getting out of her sandtrap, winter temperatures forced the rover to shelter in place with its solar arrays more or less ‘flat’ rather than tilted to the north and with no real reserve of power to stay awake. On March 22, 2010, it phoned home, responding to commands sent from Earth. And that was it.

The assumption is that Spirit, at some point after that last missive, tripped the low power fault, and turned off everything except a pair of emergency heaters and the clock and went to "sleep," programmed to collect sunlight until its batteries were re-charged.

A couple of months later, in June, as Spirit ostensibly slept, MER team member Dick Morris, of NASA's Johnson Space Center, and others announced that they had found carbonates in the data the rover collected at the base of Husband Hill from a rock called Comanche. It was a scientific coup of sorts. For decades, scientists searched for carbonates they expected were somewhere on Mars and it was Spirit that sent home the evidence. She had managed, despite everything, to close out her mission with an incredible discovery.

"I always felt the only sensible way for the mission to end is to just drive these rovers until hey can't go anymore and that's what we did with Spirit," said Squyres. "So I feel fine about that. We did what we were supposed to do, what we wanted to do."

With no favorable tilt and dust covering her arrays, the MER team believes Spirit may have simply run out of energy, and, unable to heat the electronics, succumbed, as one or more parts broke. “We knew this was going to be the worst winter yet for Spirit,” said Callas. “We had hopes. But everyone always has hopes.”

Spirit -- the pioneer rover that first looked out across the landscape just as we would, picked up rocks and dug into them, and roamed around from place to place, just like you and I if we were there -- is a monument on Mars now for explorers everywhere, a relic from a legendary planetary exploration adventure that was the first to take all of humanity on an overland expedition of the Red Planet and invite the world, anyone with a computer and Internet access, to tag along. Someday maybe – if not in this lifetime or the next, then the next – someone will retrieve the rover and bring the inimitable spacecraft home to a final resting place on Earth. Perhaps though she belongs on Mars.

In any case, Spirit leaves behind a legacy of scientific discoveries and data that will be mined for decades to come, a legacy of advances that redefine the concept of “engineering marvel,” and perhaps most profound of all, the intangible legacy of inspiration that is immeasurable and cannot be scientifically analyzed. "I really do hope that the inspiration people draw from this mission is going to lead young people to pursue careers in science and technology and engineering and things that we need to have people in this country doing," said Squyres. "That's what I really hope will be Spirit's greatest legacy."

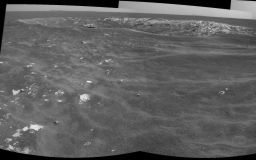

Freedom 7 Crater

Freedom 7 CraterOpportunity recorded this view of a crater informally named Freedom 7 shortly before the 50th anniversary of the first American in space: astronaut Alan Shepard's flight in the Freedom 7 spacecraft. The image combines two frames that Opportunity took with its navigation camera on its Sol 2585 (May 2, 2011). Shepard's suborbital flight lasted 15 minutes on May 5, 1961. The crater is about 25 meters (82 feet) in diameter. It is the largest of a cluster of about eight craters all formed just after an impactor broke apart in the Martian atmosphere.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

Meanwhile, on the other side of Mars Opportunity roved on and on, making tracks as fast and furious as possible for a rover of this make and model. “We've been driving on average about four sols a week and the drives have been typically over 100 meters so we've added a lot of odometry in May,” said Callas. "I'm still not willing to make any predictions about when we will arrive. But look at the map and do the math," added Squyres. "It's coming." [Doing the math: it could reach Endeavour Crater in 35 drive sols … optimistically, two and a half to three months if it can continue at its current pace.]

The next Martian winter, however, is already looming, and Opportunity is sporting quite a coat of dust. Historically, winter has never been as much an issue for this rover, because Opportunity is located closer to the equator than Spirit and it typically experienced multiple wind gusts during late spring and summer that cleared the dust from the solar panels by this time of the Martian year, and perhaps because it always seemed to have more luck.

Although Opportunity’s dust factor continued to deteriorate and power levels hovered at lower than hoped-for levels through April and the first part of May, the rover's luck may have returned a couple of weeks ago when power levels rose moderately, but notably.

Just before Memorial Day weekend, Opportunity pulled up to some outcrop to take a sampling as part of an ongoing study of the terrain the rover is crossing between Victoria Crater and Endeavour Crater. The plan called for the rover to spend a restful weekend, checking out the bedrock, then carry on driving to Endeavour, now 3.5 kilometers (about 2.17 miles) away this week.

“We're past peak summer and moving into the fall now, so energy levels are decreasing,” confirmed Callas. “For now, Opportunity is fine, and has plenty of energy to continue its 100-meter+ drives, but we're keeping an eye on her power, as well as looking ahead to the next winter.” And they’ll be on the lookout for something else too.

Farewell Spirit, RIP

Farewell Spirit, RIPSpirit, which is about the size of a golf-cart disappears on the shoulder of Home Plate in Glen Nagle's illustrative creation here. This image shows the rover's approximate position, where she became bogged down along the edge of a sand-filled crater in May 2009, in an area the team calls Troy. The panorama -- into which the rover was placed by artist Nagle -- was taken by the rover on her Sol 743, while descending from Husband Hill. Home Plate is the plateau occupying the center of the image; the rover is in the valley to its right, which on Mars is to the west.

Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell / G. Nagle

There has always been an uncanny kind of connection between the rovers, something Callas, who tended to them during their creations, witnessed in subtle and not so subtle ways over the years. They are twins after all. “It may be that Opportunity will have a sympathetic response for Spirit,” he considered. “We will be keeping an eye out for that as well."

Spirit from Gusev Crater: The Last Dispatch

Spirit sat silently throughout May, parked just to the west of Home Plate, the ancient fumarole, in Troy, her "neighborhood" for the last couple of years, right where she has been since late April 2009 as the rover ops and radio science teams at NASA and JPL listened and reached out.

Spirit's mission end

Spirit's mission endThis artistic image shows Spirit's approximate position and location in Troy, on the west side of Home Plate. Artist Astro0 has placed a two-dimensional MER into a scene created by pictures taken by the real rover. Although the angles are admittedly a little off and the disturbed soil isn't quite right, it offers the casual reader a glimpse into the present scene on Mars -- and this rover scribe thinks it's a pretty cool illustration.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / ©Astro0 2009

In recent weeks, the MER team stepped up the effort, doing just about everything humanly possible to recover the rover with an intensified strategy of scanning and commanding every conceivable frequency at all hours of the Martian days.

There are still a few other tricks they could try, Hail Marys they call them, if NASA were willing. Then they would then be able to say we had done everything humanly possible to try and get a response. "But that may well be all we would be able to say," said Nelson.

More than seven years after the little rover bounced down to a landing and a three-month tour, the prospects of ever hearing from the rover again were bleak and getting bleaker by the minute as the days of May passed. So the haunting silence that greeted the last of the electronic commands sent to Spirit on May 25th in attempts to "nudge" her into responding was not unexpected.

There is no way of knowing right now how long Spirit has been gone or what caused her to succumb. Mars will hold the answers to that mystery for a long time to come. But it may have simply been the harshness of winter. "It had to have gotten awfully cold over the winter," said Squyres. "When last we communicated with the rover, it had a flat deck and filthy solar arrays and those are fatal conditions. It probably got a lot colder than the electronics boards and other sensitive components inside the rover were designed to handle."

In the end, it won't be how Spirit died that people will remember, but how she 'lived.' Spirit took off in blue skies from Cape Canaveral on June 10, 2003 and began a 487-million-kilometer [302.6-million-mile] journey to Mars. Jostled by the same solar flare that took out Japan's Nozomi, she shook it off and flew on, arriving at Mars' doorstep right on time, but hours before she was scheduled to land, a dust storm kicked up on the planet.

The first minute of terror

The first minute of terrorThe aeroshell, as depicted here in this artist's rendering, protected Spirit, which was folded up and cocooned inside, from the fiery temperatures as she entered the Martian atmosphere on Jan. 3, 2004, US Pacific time.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

The rover’s entry, descent, and landing team, headed by JPL's Rob Manning, tweaked the spacecraft's entry parameters, and Spirit entered the Martian atmosphere at 8:29 p.m., Pacific Standard Time (PST), traveling at 12,175 miles per hour, 25 times the speed of sound. She seemed to skate through the "six minutes of terror" to landing, bouncing down as scheduled at 8:35 p.m. PST, then bouncing for what was, for some, a gut-wrenching 16 minutes, before rolling to a stop, upright and ready for duty.

"We're on Mars!" Manning announced. And with that the adventure really began.

Spirit had the world at “first beep.” More than 1 billion people, an Internet record, jammed the websites to get a glimpse of the rover's first picture postcards. So crisp, so clear, so as if you were standing right there, they left even the 'mission photographer,' Jim Bell, principal investigator for the panoramic cameras, and President of The Planetary Society, in "a state of shock and awe."

Everything seemed to be going really well … Spirit stood up, rolled off the lander and ventured onto the landscape. And then, around the time that her twin was on final approach to Mars, on Spirit's Sol 18, just as she had pulled up to her first rock and was about to take her first set of measurements, "the rover began freaking out," remembered Arvidson.

It took more than a week's worth of sleepless days and nights, but it turned out the rover's flash memory had been overloaded, putting Spirit into an endless reboot loop. "After the incredible joy of landing, we thought we might have lost the vehicle," Pete Teisinger, the first MER project manager said back then. An erase and reformatting procedure put the rover in recovery just as Opportunity was arriving. "The only drawback to debugging a system so far away is – well, imagine your slowest dial-up service provider," said software engineer Glenn Reeves, of JPL, a member of the anomaly team that rushed to Spirit's rescue.

The team didn’t think too much about it then, but the incident was the first revelation of Spirit's emerging, human-like personality. "Spirit is the willful one, and is known as the drama queen," noted Sharon Laubach, who for years was the integrated sequencing team chief for the rovers. Of course there were almost always engineering explanations, but every time the team shifted its focus to Opportunity, Spirit acted up. It was "really weird and kind of funny," she said, “but it happened again and again and again.

Maybe it's because, from the beginning, Spirit would struggle "because of her environment," while Opportunity was "Little Miss Perfect, a kind of glamour girl" that roved, carefree almost, through her landscape, noted Maxwell.

NASA chose Spirit's landing site because of evidence from Mars orbiters that indicated Gusev Crater may have actually been a lake in the distant past, a place where sediments might be found. Although Spirit did find hints of past water in the final days of the 90-day primary mission, the landscape was looking to be a somewhat disappointing rugged volcanic plain.

With nothing to lose and plenty of energy, Spirit headed for a range of hills in the distance that were promptly named for the Columbia space shuttle and crew that disintegrated on re-entry in February 2003. “We didn't know if we could drive that far – it was 2 kilometers away," recalled Nelson. "In the beginning, who knew?”

Charting a course from her landing site through treacherous terrain to Bonneville Crater. Spirit she roved on through 2004. With an average speed of 10 mm/s, she wasn't the fastest set of wheels. But Spirit made it to the Columbia Hills and almost immediately embarked on one of, if not the greatest adventure of her lifetime, a challenging, physical and emotional “bucket list” achievement, hiking a hill the height of the Statue of Liberty.

Simulation of Spirit on the flank of Husband Hill

Simulation of Spirit on the flank of Husband HillTo create this image, a computer simulation of Spirit was dropped into a Pancam panorama captured on the flank of Husband Hill on Spirit's sol 454 (April 13, 2005). The image is available in a poster-sized rendering at JPL's website (25 MB).Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech; Rover model by Dan Maas; synthetic image by Koji Kuramura, Zareh Gorjian, Mike Stetson and Eric M. De Jong

Spirit spent 2005 on the hill named for Columbia Commander Rick Husband at first hiking, sometimes agonizingly an inch at a time up its slopes. In February of that year, she found Peace, “the most interesting and important rock the rover had found,” Squyres deemed it then. It was rich with sulfate (a salt of sulfuric acid), a good sign for past water. The rover's mission had begun anew.

As Spirit continued hiking up Husband Hill, she made “an absolutely serendipitous discovery,” as Squyres called it, when she churned up some interesting stuff with her wheels as she was grappling with the hill. Paso Robles, as the team called it, boasted the highest salt concentration of any target examined to date. Turned out to be a magical March, for that same month, as Spirit was heading for Larry’s Lookout, she took the first pictures from the surface of Mars’ notorious dust devils, and experienced her first major dust cleaning which boosted her energy back to beginning-of-the-mission levels.

By April 2005, NASA and JPL officials were making long term plans for the MERs after nearly a year of continued extended missions. “They may be around for quite a while,” suggested Jim Erickson, then project manager. “Both rovers are in amazingly good shape.”

Paso Robles

Paso RoblesA team of physicists from the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada, are reporting that in their analysis of alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS)data Spirit collected from two samples of Paso Robles appear to be made up of 16% water, with an error margin of 5%. Spirit took this image of Paso Robles on Sol 399 (Feb. 15, 2005) with her Pancam.

Credit: NASA /JPL-Caltech / Cornell

In good shape, but Spirit was now slipping and sliding so much she would have to blaze a different trail if she was going to summit Husband Hill. Braving dust storms as she went, she carried on inch by inch, rover step by rover step. The pay off was soon to come.

As June rolled around, Spirit was into “the kind of geology you can really sink your teeth into,” said Squyres, and finding more compelling evidence for water-altered rocks. The rover hiked on, higher and higher, and in August Spirit reached the summit of Husband Hill, completing the 360-panorama from the summit in September, “one of the signature accomplishments of the mission,” as Squyres described it. Then, the team discovered Husband Hill had another, taller summit.

"We had a really good reason to do good geochemistry and mineralogy on the Hillary outcrop right near the summit, and it was a real tough campaign, and it paid off brilliantly, because we were able to show that the rocks there correlated with rocks far, far away, down on Cumberland Ridge," remembered Squyres. "It was one of our best stratigraphic correlations of the whole mission, but once we finished that, the science at the summit of Husband Hill was done. If the mission had only been about science and nothing else, then our job would have been to head down the hill."

On and up Spirit went, roving into the planetary exploration history books as the first rover to hike a hill the height of the Statue of Liberty, reaching the true summit of Husband Hill on Sol 635 (October 15, 2005), "when the top of the PMA was the highest point on all of Husband Hill," Squyres recounted.

“To have made it all the way to the top of that hill – and to have that moment of standing there looking around, this Connecticut-size crater beneath you, was tremendous … one of the finest moments in all of the history of space exploration," remembered Maxwell, who at time had his hands on the rover wheel, so to speak, for part of that journey.

At the true summit, Spirit basked for a while in the glow – the Queen of Mars – and took it all in – producing a panorama titled – what else? Everest. "Was there any science in that? Not really," admitted Squyres. "Was it the right thing to do? Hell yeah. To me, to this day, the Everest Pan is the best image from the entire mission." He is not alone in that assessment.

Everest Panorama

Everest PanoramaSpirit crawled to the true summit of Husband Hill to capture this breathtaking view of the interior of Gusev crater from her Sols 620 to 622 (Oct. 1 to 3, 2005). For the full-resolution image, visit the Pancam website.Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell University

On her descent, Spirit celebrated her first Martian year and took the time in December 2005 to thoroughly check out a strange looking outcrop, called Comanche. No one would know it for years, but when MER science team member Dick Morris, senior planetary scientist, manager of the Spectroscopy and Magnetics Laboratory at NASA's JSC in Houston, first looked at data from the Mössbauer spectrometer, an instrument that detects iron-bearing minerals, he knew something was different. It would take years before he openly proffered his guess, and years more of continued "pesterence" of other scientists on the MER team to sign up to conducting analyses. Spirit roved on.

As 2006 dawned on Earth, the MER crew instructed Spirit on Mars to head for the next Columbia hill, named after Willie McCool, the pilot for the shuttle Columbia. The scientists were hoping the rover could scale at least part way up onto its northern slope for the coming Martian winter.

En route, she stopped briefly in February to take a cursory look at a circular geologic formation, about 90 meters diameter, which the team named Home Plate. With the pressure on to get to a northern slope for the Martian winter, Home Plate was put on the ‘return-to’ list. Just a few weeks later, Spirit's mission took a distinctive turn.

A HiRISE view of Spirit

A HiRISE view of SpiritThe High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment, aka HiRISE, camera on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter took this image of the Spirit not long after MRO's primary science phase began last month.

Credit: NASA / JPL / UA

Her right front steering wheel had been cantankerous, seemingly sticking and stalling, and in April it failed for good, transforming Spirit overnight into a five-wheeled vehicle, a configuration that made future mountaineering "extremely tricky and potentially dangerous," as Matijevic said. “The way the wheel failed is that it locked, so doesn’t spin freely," Bruce Banderdt, MER project scientist elaborated then.

What hadn't changed was that Spirit needed to get to a northerly slope where she could tilt her solar arrays toward the Sun to take in as much of the sunlight fuel as possible, if she was going to survive. With the winter freeze taking hold, she turned around and began driving backward, dragging her locked wheel like an anchor. It was touch-and-go for a number of sols, but just in time, on her Sol 807 (April 10, 2006), the rover pulled up and maneuvered into a parked position not far from the base of McCool Hill for her second Martian winter, in an area with a northern slope the team nicknamed Low Ridge. It was a remarkable demonstration of the determination and resilience that would come to define this rover.

For seven months, Spirit investigated everything she could around Low Ridge. She took lots and lots of pictures of the nearby surroundings, discovered another meteorite, Allan Hills, named for the place in the Antarctic where so many meteorites on Earth are found, examined Halley, a loose broken up rock rich with calcium sulfate, and took the thousands of images that went into the McMurdo Panorama. In November, Spirit finally shook off winter and roved out of Low Ridge. Her destination: Home Plate, with interesting stops at targets spotted from her winter have along the way.

Within weeks, while 2007 was ringing in on Earth, a storm was dumping dust on Spirit, darkening skies overhead, blotting the solar-powered rover's source of fuel, and creating a cloud of concern that hung over the MER team throughout the New Year's holiday. The rover was forced to "emergency evacuate" Esperanza, an intriguing, spongy-looking rock, and head for a northern slope to get enough sunlight to stay alive.

Elizabeth Mahon

Elizabeth MahonSpirit took this image of the bizarre nodules that it encountered at Elizabeth Mahon on Sol 1160 (April 8, 2007) with its panoramic camera. As it turns out, this site boasts the highest silica seen on the mission to date.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

True to her MER mettle, Spirit rallied, and quickly got back to work, first investigating an outcrop named Troll, then returning to a light-toned soil patch called Tyrone for another, closer look of its sulfate rich mix. From Tyrone, the rover headed on toward Home Plate, diverting briefly to check out a “terrific geologic puzzle” called Torquas at Mitcheltree Ridge, then roving on and stopping again in April in an area adjacent to the plateau to examine an unusual outcrop with strange node features. The rover homed in with her miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES) and her alpha-particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) on one node, named after Elizabeth Mahon, a player from the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League like the other targets in the area. Well, Elizabeth Mahon turned out to be a real star on Mars, boasting a jaw-dropping composition of 72% silica. But she wasn't the only star.

The very next month, May, Spirit accidently churned up a most intriguing soil patch as she was dragging her bad wheel. "There is a silver lining to Spirit having to drive backwards dragging her wheel. We dig this wonderful, hundreds-of-meters-long trench as we drive through the Martian soil and every once in a while something interesting pops up in that trench," Squyres said then.

Gertrude Weise, as they nicknamed the churned up patch, was bright as snow. "That caught our attention," remembered Squyres. "So we looked at it with Mini-TES … this was Mini-TES' finest hour. We found an infrared spectrum that looked unlike anything we'd seen on Mars before, one that looks startlingly like amorphous silica. The APXS data confirmed the composition of Gertrude Weise to be 91-93% pure opaline silica (SiO2), significantly enriched with titanium. "It immediately became one of our top discoveries.”

Accidental silica

Accidental silicaIn the aptly-named Silica Valley, Spirit took this false color Pancam image in July 2007. It shows the silica-rich materials near Innocent Bystander, the target it accidentally ran over.

Credit: NASA /JPL-Caltech / Cornell

Spirit was in a veritable Silica Valley. "The Mini-TES spectra of the high silica rocks in this outcrop, which we found to be quite extensive, show association with an amorphous silica, meaning more like non-crystalline silica that's most commonly found around active volcanic environments where there is interaction with water," elaborated Steve Ruff, of Arizona State University, who oversaw the science on the instrument for much of the mission, elaborated after the discovery. "This is potentially the largest range or area of what appears to be aqueous alteration that we've found in Gusev."

The water story that was trickling to the surface was revealing that Gusev Crater was once "a hot, wet, violent place," as Squyres put it. "The kind of evolving understanding that we're sitting in an ancient environment where volcanic explosions were charged with magma interacting with groundwater is a pretty neat kind of revelation," Arvidson noted.

In July, as a global dust storm pummeling Opportunity blew across the planet darkening the skies over Spirit, the rover was huddled over a rock it had accidentally had run over and crumbled – and which the team – never at a loss for a sense of humor had to call Innocent Bystander. During the sols following the dissipation of the storm, Spirit checked out the innards of the rock with the APXS, and it confirmed, not surprisingly at this point, it was rich with silica.

On August 24, 2007 (Sol 1294), Spirit chalked up another record, surpassing the Viking 2 Lander's record as the second-longest-lasting spacecraft on the surface of Mars. Finally, in September, she roved onto Home Plate and began a topside tour, driving from point to point around the edge. Then, on Sol 1404 (December 15, 2007) Spirit backed right up to the rim of the circular plateau, positioned herself, and inched backward to descending just over the north edge, where she literally hung on through the season, solar arrays angled to the Sun.

Even at the hoped-for 30-degree tilt, at the depth of Martian winter Spirit would be able to produce just 150 to 160 watt-hours of power, leaving her "just about power balanced," Matijevic reported, noting that they would probably have to turn off the heater for the Mini-TES to save power, which eventually they did.

Little Bigfoot

Little BigfootThis is the Martian rock that many people believed resembled "Bigfoot" or Sasquatch and caused a veritable stir on television and the Internet in January 2008. Turns out that the Martian Sasquatch is a Martian rock spotted by a jokester looking at Spirit's West Valley panorama.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

Spirit made headlines again in January 2008. It wasn't for completing her fourth year of exploration on Mars and turning 5, but for an alleged Bigfoot sighting. The rover took a picture in which the alleged “Bigfoot” appeared weeks before from her position on top of Home Plate, among the hundreds of images she took for her West Valley Panorama. "It must have been a slow news week. Bigfoot was actually two inches tall and didn't move at all while we took all four images," chuckled Squyres shortly after the news hit airwaves around the world.

The rest of 2008 was all about surviving for Spirit. Despite the odds against her, MER-A held on through the brutally cold Martian winter. While she did survive the lowest power levels to date on the mission that year, it was not during the winter as had been anticipated, but after a dust storm hit her dead-on in early November as the Martian winter had turned to spring. During that storm Spirit demonstrated her MER mettle once more. Following power conservation instructions, she hunkering down, waited out the storm, then phoned home. “It’s going to a lot to take that rover down," Laubach remarked at the time.

Although Spirit was coated in dust and power challenged, she roved on as the Earth calendar turned to 2009, backing down from her winter position on the northern end of Home Plate, and then began a long journey around the old fumarole to two formations, an unusual pit the size of a house and a mound, named, respectively, for rocket pioneers Robert Goddard and Werner von Braun, to the south.

Spirit spent the first part of the year just trying to get around the northern edge of Home Plate. The initial plan had been to inch up on top of Home and take the short cut across the circular plateau to the other side. But her broken wheel prevented that and ultimately she had to take the long way around order to avoid troublesome terrain along the eastern side. "It was a little bit of a disappointment, but it was not unexpected," Banerdt said then. “We were sitting on a 30-degree slope, challenging driving even for a rover with six functioning wheels.”

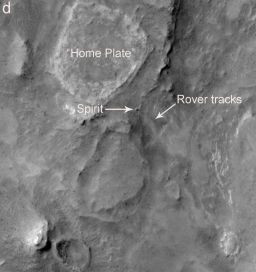

Topographic map of Spirit at Troy

Topographic map of Spirit at TroyThis topographic map of Spirit's location at Troy represents low elevations in black, purple, and blue and high elevations in red. It was developed based upon Spirit's camera images of the location, taken before it got mired at Troy. The topographic model has had a regional slope removed, which reveals that Spirit's left wheels are sitting inside a subtle depression that the team has named Scamander crater. The right-side wheels are outside the depression.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Ohio State University

Clearly, 2009 was looking to be a year of increasingly difficult physical challenges for Spirit, and certainly, Arvidson said, “it was the toughest year on record for this rover in terms of mobility." By April, the rover was only about half way to her dual-destination. Then, as that month was winding down and as Spirit was roving into an area the team called Troy, she drove right up onto the edge of a hidden, shallow, sand-filled depression (later dubbed Scamander Crater) and her left wheels broke through a crusty outer layer, sinking into the loose soil. When Spirit tried to get out, her wheels only dug in deeper, and she was ordered to stop in early May. "It's hardly surprising that we've gotten stuck,” Squyres said. “We just don't have the six-wheeled mobility system these things were designed to operate with.”

“The counterpoint is we're embedded in a geologically very rich site,” Arvidson said. And while her team on Earth experimented with exit strategies on Earth, Spirit worked on looking at everything of interest within reach, taking a lot of pictures of the area, and a lot of atmospheric measurements.

In November 2009, Spirit began the extrication process. Strangely, her right front wheel spontaneously, and only briefly, spun during a couple of tests. But in the ensuing sols the rover's right rear wheel failed, leaving Spirit a four-wheeled rover.

Nevertheless, by January 2010, even as NASA officials held a press conference to reassign Spirit to lander status, she was making visible progress. During the next couple of weeks, she inched a total of 13 inches closer to freedom, but winter and fate stepped in, and the rest of the story is fast becoming history.

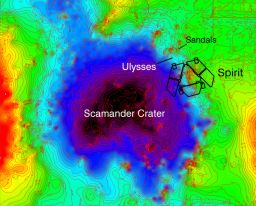

Orbital view of Comanche

Orbital view of ComancheSpirit began its Mars exploration at its landing site in January 2004. As of May 2009, the rover has been mired in a sand-trap in an area called Troy, on the western edge of Home Plate. In Dec. 2005, Spirit inspected an outcrop called Comanche during her descent from the summit of Husband Hill toward Home Plate, and found a high concentration of carbonate, indicating that a past environment at this location was wet and non-acidic, possibly favorable to life. The locations of the landing site, Husband summit, Comanche and Troy, along a yellow line tracing Spirit's route, are shown here on a portion of an image taken by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter on Nov. 22, 2006.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA

Spirit has been there, just to the west of Home Plate, ever since. She made it through all the steps to prepare for the anticipated low power fault that would send her into the hibernation mode, and sent her last electronic communiqués on March 22, 2010. “We were all pretty surprised that the rover was still talking to us then,” recalled Squyres.

No one can say for sure, but many who know this rover believe Spirit may have still been alive and in hibernation on April 29, 2010, which would mean she did in fact surpass Viking Lander 1's longevity record of six years and 116 days on the Red Planet. And it would be just like her to have hung on until June 3, 2010, to know the Comanche research was published in Science, and to revel, however quietly, as it rocked the planetary science world.

The discovery of carbonates on Mars is a major scientific finding. Comanche’s magnesium iron carbonate composition is compelling evidence for past near neutral water. In other words, water that is more alkaline, more like we know it, and more conducive to the emergence of life than the highly acidic water, evidence for which both rovers found.

Spirit may have carried out her mission on her terms, but in the end it worked. She made a spectacular entry onto Mars, worked above and beyond the call of duty, and went out with scientific "hit" that rewrites the planetary science texts. Now the golf-cart size rover sits, ostensibly for eternity in the middle of an ancient "ghost environment," where volcanoes erupted, fumaroles hissed caustic steam, and hot springs bubbled and spit.

Daily flight ops, not to mention their day-job responsibilities, have so far prevented the MER scientists from doing much more than digging into the tip of the iceberg of Spirit data. There are no doubt, more discoveries and surprises to come as the research and analyses are done, but with Opportunity roving on, don't hold your breath just yet.

Opportunity is keeping most of the operations team pretty busy, which by all accounts is a good thing. Still, there is real emotion about the loss of Spirit. "Some people here have a very strong attachment,” acknowledged Callas.

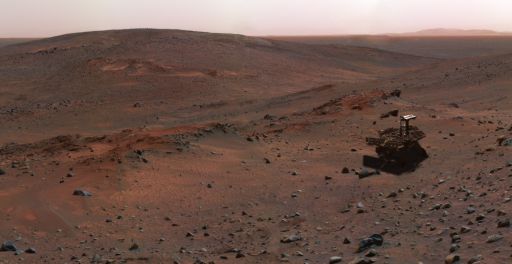

The little rover that did

The little rover that didSpirit landed on Mars Jan. 3, 2004 (PST) and for more than six Earth years (three Mars years) roamed around Gusev Crater. The rover put a total of 7,730.50 meters (4.80 miles) on her odometer, sent home more than 124,000 images from the surface along the way, and captured hearts around the world. Rover model by Dan Maas; synthetic image by Koji Kuramura, Zareh Gorjian, Mike Stetson and Eric M. De Jong.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

Given their appearance, their personalities, their admirable work ethic, it's almost impossible, even for most of the scientists and engineers who have worked with the rovers since the beginning, not to anthropomorphize Spirit. "What we're doing of course is projecting our emotions onto a machine," acknowledged Squyres. "I mean it's a hunk of metal. The rover is not a living creature, and yet we talk of accomplishment, of tenacity and courage, sadness and death and all these human traits and emotions."

Those traits and emotions though are the most human aspects of robotic exploration. They are what endeared Spirit to people everywhere around the world. And as human and un-robotic as it may be, Spirit will be remembered not as a hunk of metal, but as the little rover that could, the rover that never did say 'never.’ And on a personal level, the bond does go deep for some of her crew on Earth. "Spirit occupied this place in my life and I know I'm going to be unconsciously looking around for her,” reflected Maxwell. “The plus side of that it will be this great little constant reminder of how important a part of my life she was, and of all of our lives,” he added optimistically. “Job well done, baby.”

For such a little rover, Spirit leaves an awful big legacy. But beyond the scientific discoveries, beyond being the engineering marvel that she was, this rover’s greatest contribution to the human race just may be the inspiration she gave people around the world to believe in dreams, not matter how impossible they may seem.

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

Opportunity began the month of May taking a tour a small field of young impact craters along the chosen “pink path” to Endeavour Crater. “Opportunity is drive, drive, drive,” said Arvidson, reiterating the mantra and mission directive fore the rover since it took off from Victoria Crater back in September 2008.

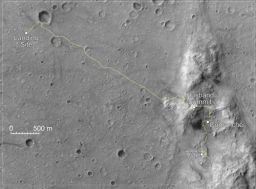

Opportunity route map

Opportunity route mapThis route map shows Opportunity's travels through this month, May 2011. It was assembled and annotated by Eduardo Tesheiner, of UMSF.com, who has been contributing route maps to this Update for years.Credit: NASA / JPL / UA / MSSS / E. Tesheiner

The pink path is the route the MER team chose for Opportunity to take to the southern tip of Cape York, where it will make the first "landfall" at Endeavour Crater. The path "bows" to the north from the straight-line path, "but the extra drive distance relative to the crow line is only 150 meters,” said Arvidson. "Plus it takes the rover past scientifically interesting bedrock, craters, and what [JPL planetary geoscientist] Tim Parker calls gravel bars, which that may be filled craters. We're doing reconnaissance science, largely drive-by shootings as we go," he added.

After driving out of April on her Sol 2583, cautiously navigating near the craters with a drive of a little more than 120 meters (394 feet), Opportunity kicked it on May Day. But on her Sol 2585 (May 2, 2011), the rover took off again, driving 28 meters (92 feet) due south, heading between the two largest craters, nicknamed Friendship 7 and Freedom 7. On the next sol, the rover made a 7-meter (23-foot) approach toward the crater Freedom 7 to carefully take some pictures of the interior. In honor of the 50th anniversary of the first American into space, Alan Shepard, the MER team dubbed the craters in this impact field after the spacecraft of NASA’s Mercury Program.

With energy levels hovering between 360 and 408 watt-hours in May, Opportunity was sporting plenty enough energy to drive, even though the atmospheric opacity kept the skies really hazy with the Tau registering .819. “Wish for a dust-cleaning event,” said Arvidson earlier this month.

To safely navigate around and out of the crater field and onto the south and Endeavour, Opportunity performed a "dog-leg" maneuver first due south, then due east, on Sol 2587 (May 4, 2011), and then headed east with a drive of more than 126 meters (413 feet) the following sol, and almost 129 meters (423 feet) on Sol 2589 (May 6, 2011).

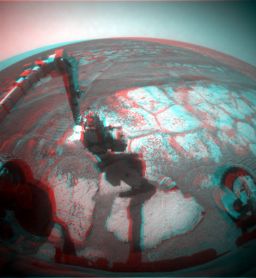

Opportunity at Valdivia in 3-D

Opportunity at Valdivia in 3-DOpportunity pulled up to this slab of bedrock just before the Memorial Day weekend, to rest and take a routine sampling. Stuart Atkinson rendered this image, which shows the rover at work at Valdivia, in 3-D. Get you red/blue glasses and enjoy.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech /Cornell / S. Atkinson

The rover spent the next three sols taking care of routine engineering and science business, and resting. Then on Sol 2592 (May 10, 2011), she took off again, driving east another 126 meters (413 feet), clicking off kilometer 29 – or mile 18 – on her odometer. On a definite rover roll, Opportunity would drive four more times during the second week of May.

On Sol 2593 (May 11, 2011), she roved east for 117 meters (384 feet). The science team saw an interesting crater in the distance during that jaunt, dubbed it Skylab, and on the next sol, they commanded the rover to drive 72 meters (236 feet) to stop near the crater to take a few pictures before moving on.

Opportunity then headed to the southeast with a drive of more than 91 meters (300 feet) on her Sol 2595 (May 13, 2011), following it with an even longer trek further southeast the next sol, during which she logged more than 140 meters (460 feet).

After a couple sols of rest, Opportunity took off again on Sol 2599 (May 17, 2011), roving southeast then east for more than 86 meters (282 feet). On the next sol, the rover put more than 112 meters (367 feet) on her rocker bogie, utilizing the dog-leg maneuver mid-drive in order once again, to do some close-up imaging of a crater.

Around this time, Opportunity's power levels climbed above 400 watt-hours, a little less than half of what it had when it first landed. "We may have had a minor cleaning event, but it's so close to our general uncertainty that it's hard to say," said Nelson.

On Sol 2601 (May 19, 2011), Opportunity headed out on yet another long drive, but her trip was cut short by a cosmic ray-induced single event upset (SEU) in the electronics of one of the motor control boards. The rover safely stopped after only 29 meters (95 feet) when the event occurred and both the vehicle and the electronics are fine, JPL reported, noting "[t]hese events happen from time to time."

Opportunity picked up again on Sol 2603 (May 21, 2011), with a drive of nearly 129 meters (423 feet) to the east/southeast. During the drive, the rover performed a tank turn test. This is a maneuver where the rover drive one side or set of wheels forward while driving the other set of wheels on the other side in reverse to turn in place like a caterpillar or tank would. It's a way for the rover to turn without using the steering actuators.

Valdivia

ValdiviaOpportunity took this image of Valdivia on her Sol 2608 (May 26, 2011) and Stuart Atkinson, of UMSF.com, and the rover poet-artist, processed it. The rover is taking a break and conducting some routine science on this plate of bedrock, part of an ongoing terrain campaign the rover has been conducting since Victoria Crater.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech /Cornell / S. Atkinson

While the tank turn test was successful and Opportunity achieved the desired turn in place, the maneuver actually puts more wear on the drive actuators, which are already operating beyond their guaranteed "lifetime" of revolutions, while the steering actuators are actually hundreds of thousands of revolutions under their "lifetime warranties;" thus, it's not likely to be employed soon.

Since Opportunity was overdue in sampling another section of bedrock for the ongoing Meridiani terrain study, when the science team saw a decent target area ahead last week, it decided it was time. “We don't want to waste any of the drive time and we'll be going over extensive outcrops, but we were overdue for the bedrock sampling," confirmed Arvidson.

So, following some routine dust monitoring and picture taking on Sols 2604 and 2605 (May 22 and 23, 2011), Opportunity drove a modest 41 meters (135 feet) on Sol 2606 (May 24, 2011) to the east/southeast, up to the chosen outcrop to check it out with the instruments on its instrument deployment device (IDD) or robotic arm. It looks to be the northern edge of a geologic transition the rover will cross.

After spending Sol 2707 (May 25, 2011) taking Navcam 360 images and monitoring the dust in the sky overhead, Opportunity performed a .53-meter bump on her Sol 2708, putting herself in good position on the bedrock, and bringing her total odometry to 29,908.73 as the holiday weekend got underway.

Opportunity's right front wheel continues to show modestly elevated motor currents but right now the engineers aren't terribly concerned. “We're not sure what it means, but we watch it everyday like a hawk,” Callas said. "This is the wheel that has the failed steering actuator and it's toed in slightly by 7 degrees, is that the reason? It's also the same wheel on Spirit that failed. Is it a precursor to more serious problems? We can't say. The only thing I can say is that we're at 29.9 kilometers right now, so we're less than 100 meters away from crossing 30 kilometers for a system designed for one kilometer.”

The plan called for Opportunity to do some remote sensing during the Memorial Day weekend, sample the outcrop and hit the Meridiani highway again this week. "We're at a steep rate of travel right now and just 3.5 kilometers from first landfall from Endeavour," Callas reminded.

"What was that other mission--?" asked Arvidson, tongue in cheek. "Oh yeah, Spirit."

"The wheels could fall off tomorrow. I'm making no promises, you know that," cautioned Squyres. "But things have been going well lately and we'll take it one day at a time."

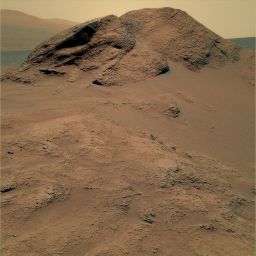

The art of Endeavour

The art of EndeavourOpportunity took this image of the Endeavour hills in March, and Stuart Atkinson, of UnmannedSpaceflight.com, turned it into this artistic image. "The Sun is "added," and the colours are all fake, and it's tweaked to within an inch of its life, poor thing, but apart from that it's an accurate view," Atkinson notes with a smile.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / S. Atkinson

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth