A.J.S. Rayl • May 31, 2010

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Spirit Sleeps through Solstice, Opportunity Cruises Past Viking Record

The Mars Exploration Rovers made it through their fourth winter solstice in what is the coldest, most challenging Martian winter the twin robot field geologists have experienced.

It was all quiet on the Gusev front as Spirit hibernated throughout May presumably recharging her batteries. On the other side of the planet at Meridiani Planum, Opportunity continued onward slowly but relentlessly toward Endeavour Crater, surpassing the Viking 1 Lander's longevity record along the way. That makes Opportunity, which landed on Mars three weeks after her twin in January 2004, the second longest-lived robot on Mars, pending Spirit's awakening.*

"It is the toughest winter certainly for Spirit," said John Callas, MER project manager, of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where the rovers were 'born' and are being managed. The team anticipated Spirit would go into hibernation mode months ago, because the amount of sunshine hitting the robot's solar panels declined during autumn in Mars' southern hemisphere, and mobility issues had prevented the rover from positioning itself with a favorable tilt north toward the Sun, like it had during the last three Martian winters.

Although Opportunity has managed to keep moving as past in winters, the rover, despite its location nearing the Martian equator, clearly felt the bitter freeze of the season this month. The module that houses the rover's main computer or "brain" continued getting colder as the temperature outside dropped lower and lower. Like last month, the rover handlers employed the tried and true countermeasure of keeping the rover awake longer. Just like humans stay warmer in freezing cold conditions if they're awake, these rovers produce life-saving warmth when systems are on. But, as the month progressed, the energy it took to stay warm cut into Opportunity's ability to drive.

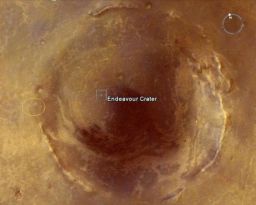

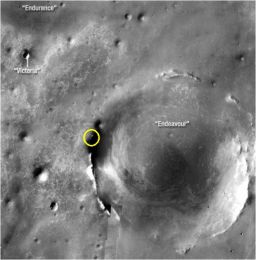

Landfall site chosen at Endeavour

Landfall site chosen at EndeavourThis image taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter is circled here to show the general location where the MER team plans to have Oppotunity make "landfall," so to speak, at the rim of Endeavour Crater. The University of Arizona's High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment, aka HiRISE, led by Alfred McEwen, has aided the MER team is directing the rovers, especially Opportunity as it journeys across Meridiani Planum to its still distant destination of Endeavour Crater.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / University of Arizona / labeled by Stuart Atkinson

Just when she needed it however, lucky Opportunity got a little boost from Mars this month as the planet produced a pleasant little wind gust that cleared a bit of the accumulated dust off the solar panels, giving the rover a little more power. "It wasn't a huge event, but every watt-hour counts at this point," said Steve Squyres, of Cornell University, the principal investigator for rover science. "It enables more driving and that's what its' all about with Opportunity these days."

Beyond that, winter solstice in the southern hemisphere of Mars, the day of the Martian year with the least sunshine at the rovers' locations, came and went on May 12 (May 13 Universal time), and so the rovers experienced the very depths of this brutal season this month and now a brighter, sunnier future appears to be just around the proverbial corner. With a little imagination, one could almost hear both Spirit and Opportunity heave a robotic sigh of relief.

During the next 12 months or so, as winter gives way to spring and spring becomes summer, the Sun will rise higher and higher in the sky, beaming down more sunlight and photon fuel for Spirit and Opportunity to rove on with newfound energy. Unless dust interferes, which is unlikely in the coming months, the solar panels on both rovers should gradually generate more electricity. "Passing the solstice means we're over the hump for the cold, dark, winter season and we're expecting the energy levels and temperatures to start going up in the coming weeks and months," confirmed Callas.

The team is cautiously confident that Spirit will awaken from hibernation at some point during the next several months, start communicating and resume work. Opportunity, meanwhile, will no longer have to rest to recharge her batteries between driving days and will be able to pick up the pace on the long journey to Endeavour.

Opportunity's port at Endeavour

Opportunity's port at EndeavourThis image taken by the University of Arizona's High Resolution Imaginging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter gives you an idea of where the MER team plans to have Opportunity pull up to Endeavour Crater. At least for now, this is general area where the rover is slated to arrive and begin its tour.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / UA / labeled by Stuart Atkinson

Now, as June takes hold, Spirit and Opportunity are nearing the end of the 77th month of their truly excellent, often harrowing, sometimes miraculous expedition, a tour originally planned to last just three-months.

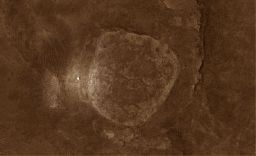

Spirit remains parked in the same location of course at Troy on the western side of Home Plate, the circular volcanic plateau she has roved up and down and around, her odometer still reading 7,730.50 meters (4.80 miles). Although the rover has not phoned home since Sol 2210 (March 22, 2010), the team believes Spirit experienced a low-power fault in late March during which she turned off all sub-systems, including communication, as designed and programmed to do, and is now using what available solar array energy there is to recharge.

"We do have models, but those models depend on the amount of dust on the solar panels, and in the atmosphere, as well as the rover's power levels, and right now we have no way of checking any of those," pointed out Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St Louis. We have no idea how Spirit is doing other than theoretically. The vehicle is on its own," added the deputy principal investigator who generally has been overseeing Spirit's scientific agenda since the beginning of the mission.

When the batteries are sufficiently charged, Spirit should wake up and try to communicate over her X-band antenna, a communiqué that would go straight to Earth via the Deep Space Network (DSN), an international network of antennas that supports interplanetary spacecraft missions, as well as radio and radar astronomy observations. Once awake, the rover is programmed to trip an up-loss timer fault that will enable it to communicate over an ultra-high frequency (UHF) radio signal via the Mars Odyssey orbiter. The team doesn't really expect to hear from Spirit until August, September or October, maybe November, "but we're listening every day," Callas said.

Simulation of Spirit's predicament

Simulation of Spirit's predicamentThis artistic image -- in which Astro0, a member of UnmannedSpaceflight.com, has placed a two-dimensional MER into a scene created by pictures taken by the real rover -- approximately illustrates Spirit's current position at the location in Gusev Crater known as Troy. Although the angles are admittedly a little off and the disturbed soil isn't quite right, it offers MER Update readers a glimpse into the rover's scene on Mars.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / ©Astro0 2009

In the meantime, team members are using the extra time to catch up on all kinds of things, said Bruce Banerdt, MER project scientist. "Listening for Spirit does require some planning and certainly Opportunity is going strong and is in full operation even through she's not able to drive everyday, so we are still busy. But we do have the opportunity to do some housekeeping and take care of some projects that have been pushed to the back burner for a while," he said.

Opportunity began the month with low power levels, but enough energy to continue making short drives, so pushed ever onward toward the 22-kilometer (13.70-mile) diameter Endeavour Crater, making rest stops along the way to recharge her batteries. By the second week of the month though, the rover was using a considerable bit of her small amount of sunlight fuel just to stay awake and keep her electronics warm. That meant of course it took longer to recharge her batteries, which in turn further limited her driving. But if Opportunity had not expended the energy to keep warm, a pair of thermostatic, survival heaters would have automatically turned on and consumed so much energy the rover would have been left at a standstill.

The rover engineers, however, are always strategizing and this month they saw an opportunity for Opportunity. The rover, they figured, could take advantage of the sea of sand ripples that stretch our before her by ending her drives parked on the northern face of a ripple to angle her solar arrays in a more energy-favorable tilt, Immediately, the rover began to implement this 'lily pad' strategy, as the rover engineers dubbed it. Although the energy required to carryout the final positioning sacrificed a little distance on each drive, the strategy worked and Opportunity carried on.

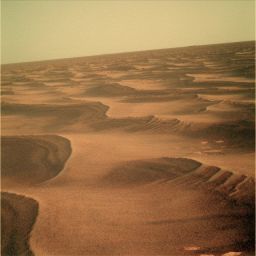

A sea of ripples

A sea of ripplesOpportunity took this mesmerizing image of the sea of ripples with her panoramic camera on her Sol 2229 (May 2, 2010). The rover is doing a lot of driving around and over the sand waves these sols at Meridiani Planum. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / enhanced by Stuart Atkinson

"The ripples look like waves on the ocean, like we're out in the middle of the ocean with land on the horizon, our destination," said Squyres. Indeed, the rim of Endeavour is on the horizon, and so the prize, the next big attraction for Opportunity is in view and the rover's 'eyes' are on it. In fact, Opportunity sent home the first postcards of the hills of the crater rim late in April and they ran in last month's MER Update. The Pancam team was at work processing new color images as this report went online. Although Endeavour is there for us all to see, the crater rim is still some 11-to-12 kilometers (6.8-to-7.4 miles) the way the rover drives. It will take Opportunity at least a year to get there in the best of all possible circumstances.

The MER team chose Endeavour as Opportunity's next big attraction back in September 2008 after the rover had finished two years checking out the smaller Victoria Crater, knowing that even this larger hole in the ground would take the mission even further back in Martian time. Since then, the really big crater has become even more alluring because orbital observations indicate that there are clay minerals exposed at Endeavour and clay minerals are important evidence of past water never examined up close and personal on the Martian surface. This month, Opportunity finally made the turn from south/southeast to the east, Squyres said, and is now visibly on the path direct to her destination. "Even though we know we might never get there, Endeavour is the goal that drives our exploration," he added.

That's not to say the team isn't optimistic about Opportunity's chances, because they are, and they've got every reason, every scientific motivation to get the rover to Endeavour. "The clay minerals at Endeavour speak to a time when the chemistry was much friendlier to life than the environments that formed the minerals Opportunity has seen so far. We want to get there to learn their context. Was there flowing water? Were there steam vents? Hot springs? We want to find out. And we would like to get to the clay minerals before MSL [Mars Science Laboratory] does," Squyres said in an interview Friday.

On or about May 20, Opportunity's Sol 2246, Mars whipped up that little gust of wind that blew some of the dust off her solar panels, resulting in "a 10% bump on our solar panel," informed Banerdt. "That's given us more energy and we have since been driving a little longer and planning more drives," added Callas, "so we're not as restricted as we were earlier in the month.

Viking lander

Viking landerThe Viking 1 Lander conducted surface operations on Mars for 6 years and 116 days and until last month held the longevity record for a robot working on Mars. MER Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson served as the the Viking Lander imaging team leader from 1977 to 1982. Credit: NASA

The gust also lifted a little more dust from the panoramic camera lenses, confirmed Planetary Society President Jim Bell, of Cornell University, the Pancam's lead scientist. "The lenses have been clearing little on and off for quite some time actually, but this time it was noticeable and that's a good thing," he said.

A good thing and another good omen especially when you realize that Opportunity cruised that very same sol, or Martian day, past the Viking 1 Lander's longevity record of six years and 116 days.

The Viking 1 Lander, which rocketed down to the surface on July 20, 1976, will always be remembered for being the first successful mission to the surface of the Red Planet. But this month Opportunity roved on to take her place in history as the second longest-lived robot on Mars, right behind her twin.

"Opportunity, and likely Spirit, surpassing the Viking Lander 1 longevity record is truly remarkable, considering these rovers were designed for only a 90-day mission on the surface of Mars, but it's not so much that they've lasted so long," Callas reflected during an interview late last week, "it's that they're doing so much on Mars."

Just five days after that achievement, the MER team on Earth gathered at JPL for its annual meeting. "The team meeting was really one of the best in terms of science that we've ever had," said Arvidson. "The RPs [rover planners] and the engineering staff attended and we had a very good, very productive discussion."

Passing the torch

Passing the torchOn May 20, 2010, Opportunity surpassed the Viking 1 Lander's longevity record for a robot working on Mars, becoming the second longest-lived surface mission just behind Spirit. The Viking lander operated for on Mars of 6 years and 116 days and only stopped because of, ouch, a human error in transmission. For Opportunity 6 years and 116 days translates to 2246 sols or Martian days. Credit: Astro0 / UnmannedSpaceflight.com

Now well into its seventh year, the mission has gone on for so long that some crewmembers have moved on to forthcoming missions, like MSL, and new, younger team members have come onboard fresh out of college.

"We all know voices because we interact by teleconference all the time, but, since we only get together once a year now, connecting a voice to a face is really nice," added Bell. "Getting the team together recharges us and it was really great to see people doing exciting things, pouring through old datasets and pulling out new discoveries."

"We've got a long, long way to go before we finish mining all the nuggets from the stuff we've already got, much less the discoveries yet to be made," Banerdt agreed.

"With 20,000 meters and counting of traversing, hundreds of thousands of data products, and lots of sites and targets measured, there's a lot of synergistic science coming about now, so we're able to compare this measurement to that measurement, and have enough time to put some pretty deep thoughts together," Arvidson elaborated.

The MER team spent significant time discussing strategic science plans for both rovers. For Spirit, the talk focused on plans of what to do when (not if, interestingly) the rover wakes up. "The meeting was totally upbeat and no one," said Arvidson, "was talking like 'this was a really good mission.' There's an expectation that it will be business as usual in October," he added. The agenda laid out earlier this year pretty much holds.

Since Spirit has lost the functionality of two of her six wheels, the rover is handicapped in the ability to take long jaunts in the rugged terrain of Gusev. "Even with four-wheel drive though, the conclusion at the meeting was that it is such a target-rich environment in terms of these crusts that even short drives of centimeters to tens of meters is well worth the investment of time to free Spriit," said Arvidson. Thus, there is, it would seem, every intention to get Spirit out of the sandy snare that had impaired her mobility for a full year before the Martian winter set in.

The discussion about the plan for Opportunity focused on "which way to drive, what we're going to do along the way, including characterizing the bedrock and the ripples, what we're seeing off the horizon, what we expect to see at Endeavour, and how that relates to what we've seen from CRISM, CTX, and HiRISE, juxtaposed with papers based on six and a half years worth of data," summed up Arvidson.

The Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM), Context Camera (CTX), and the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) are each onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). Arvidson is head of the Surface Geology subteam for CRISM. Squyres is a co-investigator on the HiRISE team.

Opportunity's prime directive of course stays the same: get to Endeavour. And during the meeting, the team firmed up the decision on where the rover will make "landfall" at the big crater. "We're going to go to the nearest spot on the rim," announced Squyres. "We kind of had that established already. This isn't a time to mess around."

Endeavour has always been alluring because it is just so darn big, meaning that it exposes much older environments deeper below the surface than the rover has been able to view anywhere else. But now, with a little help from the rovers' orbiter friends, there's even more reason for Opportunity to put the pedal to metal and haul as fast as she is robotically capable. "Through CRISM, we have evidence now for putative phyllosilicate signatures from the Noachian crust," said Arvidson. The Noachian epoch between 4.6 and 3.5 billion years ago, is when the oldest extant surfaces of Mars formed, a time marked by many large impact craters. Many scientists believe that there was extensive flooding by liquid water late in the epoch.

The engineers and scientists do still on occasion manage to marvel, if only momentarily, at what their charges have done. "It is amazing we're still acquiring important new data, but on the other hand it's also explainable because they're rovers," noted Banerdt. "We could have sent a thousand landers to Mars, but we found a more economical way of doing it – just send two rovers and have them move to a new spot every couple of days or so. I think," he added, "we've found the secret."

Spirit from Gusev Crater

Spirit still shining at Troy

In this picture of Home Plate, taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, you can easily see the stark white figure that is Spirit to the left (west) of the geologic formation in this image enhanced by rover poet Stuart Atkinson. "It's just a screengrab from the excellent HiRISE IAS Viewer," he said. "I added some colour, then highlighted the position of Spirit. If you look carefully you can see bright trailing leading to Spirit, the result of the (right front) broken wheel being dragged through the dirt, churning up brighter material beneath." The rover is currently in hibernation waiting for the Martian winter to end. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / enhancement by Stuart Atkinson

While MER team members haven't heard so much as a beep from Spirit, they really don't expect to until October, general consensus holds, said Arvidson. "It's uncertain because it depends on whether it gets a dust cleaning and other variables. But it's clear that Spirit is on its own."

With no idea of when Spirit will wake up, engineers at JPL have been relying on the Radio Science Receiver (RSR), which is connected to the DSN, to listen for any X-band signal that might come through the network of receivers. Mars Odyssey is also listening for the rover's signal during pre-scheduled UHF relay passes.

"We structured the fault response of Spirit so that when it does have a low power fault and then wakes up, she will also initiate an uploss timer fault that would enable the rover to not only use the X-band, but also use some of these communication passes that we put in the table onboard the rover to communicate with Odyssey," Callas explained once again. "We did this as a sort of belted suspenders, just in case the X-band transmitter after being in this cold weather no longer works."

While there's no particular reason to think the X-Band will fail, "when the rover wakes up, it's likely that a few components won't survive," warned Callas. "This way, we have an independent way of hearing from the rover via the UHF system; therefore, the rover will try to use the UHF in addition to the X-band."

Although no one on the team is really expecting that Spirit is trying to send a message through the DSN or Odyssey yet, since neither rover has ever gone into hibernation before, they have no idea how long it will actually take the rover to recharge and phone home. "So we're listening everyday anyway," said Callas.

Do rovers dream of electric sheep?

Do rovers dream of electric sheep?Do rovers sleep? Yes, in fact, they do in a robot kind of way. But whether they dream of electric sheep? We're just paying homage to author Philip K. Dick whose 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep is a science fiction classic. To be perfectly honest, far as we know, the rovers' "eyes" don't glow blue, but we thought this was such a cool artistic rendering by Stuart Atkinson of UnmannedSpaceflight.com that we are posting it for rovers fans everywhere, just for fun. For more of Atkinson's artistic renderings: check out: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / created by Stuart Atkinson

Silent though Spirit may be, listening for her signal means there is still some planning and "a low level of work" continuing on this rover. "For the direct-to-earth links, there are people involved who are outside the project, the radio science people here at JPL who are using the RSR to listen during the X-band windows every day that are pre-programmed on Spirit," said Banerdt. "So, the RSR at JPL is turned on and someone in the radio science group checks that out, then within a couple of hours the entire MER tactical team at JPL gets the update that goes out in an email distribution."

Complicating matters is the fact that the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and Spirit share the same frequency. "The RSR however is able to look at the signals that come in through the DSN and the engineers do a Doppler analysis on it," Banerdt explained. "The Doppler signature on an orbiting spacecraft is different than the Doppler signature of a spacecraft on the planet, because they're moving at different velocities, so the radio science team is able to look at the Doppler signature within the wavelength band and make a determination if Spirit is trying to communicate."

What will happen when Spirit does send that first beep home? "Once we receive that indication basically everybody on the project would get together and evaluate what we do next," Banerdt said. "Probably we would ask MRO to forego their transmission during the next window and try to lock on to Spirit's signal. Whatever we decided, it would be a pretty fast turnaround."

Not talking to Spirit has meant an adjustment for the team, both in terms of time and emotions. So far, everyone seems to be adapting. "We've gotten used to it," said Banerdt. "We had been struggling with keeping Spirit on an even keel and getting the most survivability per given watt-hour of power as we could before winter set in. When we lost contact, it was kind of jarring even though we were expecting it. But we did have her in pretty good shape going into that."

For the most part, Callas added, "people are just doing their jobs."

Even so, as project manager, Callas planned another team-building trip this month, a field trip to the Goldstone Deep Space Communications Complex, aka the Goldstone Observatory, in the Mojave Desert of California. It's part of the DSN and is operated by ITT Corporation for JPL.

"This isn't a standard situation with Spirit, so it's hard to know how accurate our models are in terms of temperatures and power," reminded Banerdt. "Our best estimate is that the rover will try to communicate in the late August-September-October timeframe. But the scientists and engineers are sort of used to trusting the team's calculations and I think people are really pretty confident that come September or November or whenever that she'll pipe up and we'll be back in business again."

As another month of silence passes, optimism is still measured about Spirit's awakening, but one thing is certain: no one yet is betting against this rover. "Just when you might think she's knocked down, Spirit has always popped up with something new and wonderful," reminded Banerdt. "The rover drivers have not given up on mobility yet, and were pretty encouraged by her performance before winter set in."

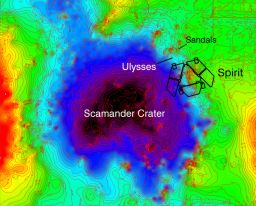

Topographic map of Spirit's location at Troy

Topographic map of Spirit's location at TroyThis topographic map of Spirit's location at Troy represents low elevations in black, purple, and blue and high elevations in red. It was developed based on rover images of the location, taken before it got mired at Troy. The topographic model has had a regional slope removed, which reveals that Spirit's left wheels are sitting inside a subtle depression that the team has named Scamander crater. The right-side wheels are outside the depression. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Ohio State University

Moreover, everyone seems in agreement that even if Spirit's roving is limited to the neighborhood around Home Plate, this rover has a lot more to do before she goes offline for good. "Perhaps the discoveries won't come as fast and furious," said Banerdt, "but the rover still has some pretty substantial contributions to make."

Spirit's science agenda was laid out earlier this year. It includes further characterization of the sulfate-rich soils around the rover, an extensive study of the atmosphere, and a long-awaited, much-anticipated radio science study to record the wobble in the planet's axis of rotation, research that will determine the diameter, density, and make-up of the planet's core.

Patiently, JPL's William Folkner has waited for the whole mission to do the radio science research. However ironically, this research can only be done with an immobile rover, and if that's all Spirit managed to accomplish before the end, it would be one heck of a way to end her part of the mission, for determining whether Mars' core is liquid or solid would rewrite the textbooks and put another major exclamation point behind an already distinguished, legendary mission.

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

Despite the colder-than-freezing temperatures, Opportunity began the month with power levels of around 245 watt-hours, under slightly hazy skies, recording an atmospheric opacity or tau of 0.322. The rover measured a dust factor of 0.462 on her solar arrays, meaning she was only utilizing about 46% of the available sunlight. Even so, Opportunity had enough energy to rove into May, taking a quick jaunt of about 29 meters (95 feet) on Sol 2228 (May 1, 2010), and then drive two more times during the first week of the month.

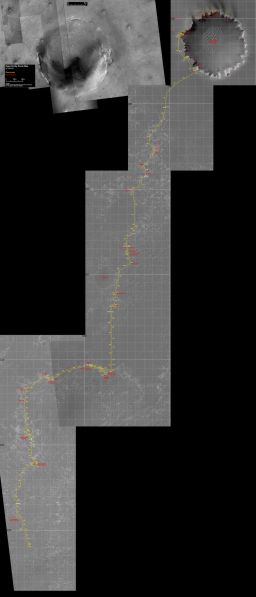

Opportunity route map

Opportunity route mapThis route map, which was put together by MER aficianado Eduardo Tesheiner, a senior member of UnmannedSpaceflight.com, is comprised of images taken by the HiRISE camera and CTX cameras onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and shows Opportunity's route from Victoria Crater to April 2010.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / UA / MSSS / Eduardo Tesheiner

While resting to recharge on her Sol 2229, Opportunity took part, remotely, in an Earth-wide photography event held by the New York Times. The newspaper's photography blog, Lens, actually proposed the event, called "A Moment in Time." The objective was to collect and post thousands of pictures from different locations around the world, each taken precisely at 1500 Universal Time (UT, or Greenwich Mean Time) on May 2.

It was actually The Planetary Society's science and technology coordinator, Emily Lakdawalla, who offered up the suggestion for Opportunity to take part, wondering "wouldn't it be cool if we could take this project to a whole 'nother planet?" She covered the event extensively in The Planetary Society blog.

"The team was very enthusiastic and supportive," recounted Pancam lead scientist Jim Bell, who is credited with the picture, and who just happens to be the Society's current president. So the rover team beamed up commands for Opportunity to take multiple exposures late in the Martian afternoon that day – and the rover snapped on command.

Because of logistical reasons, Opportunity actually took her pictures just before 1500 "local true solar time" on Mars, which was in reality a few hours earlier than the event called for on Earth, about 1115 UT on May 2 on Earth to be exact, "a bit of a fudge," as Lakdawalla put it. But 15:00 UTC corresponded to 18:14 local true solar time that sol and it simply would have been too dark for Opportunity to get anything. Shortly after taking her photograph, the rover transmitted the image dataset to Odyssey, which in turn relayed it to Earth.

"It wasn't until about 1500 Universal Time on Earth that we could actually see the images and combine them into a mosaic," Bell rationalized. "So we shot the mosaic on Mars at around 1500 local Mars time and received and processed the image on Earth around 1500 Universal Time and hoped that our entry was consistent with the spirit of the rules, and that we could make this a truly interplanetary event."

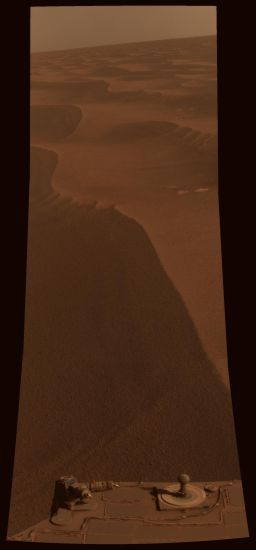

A Moment in Time

A Moment in TimeTwo worlds, one sun: while humans' lives unfolded on Earth, the Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity paused in its southward trek and captured this photomosaic. Dusty, reddish-brown sand dunes stretch to the horizon in a view taken around 15:00 local Mars time on May 2, 2010. That's the caption submitted along with this photo to the New York Times Lens blog's "A Moment in Time"project, which solicited people around the world to take a photo near 15:00 UTC on May 2 to document the variety of human experience at a given moment. The Planetary Society's Emily Lakdawalla convinced Society President and Panam lead scientist Jim Bell that Opportunity should take part. She later chronicled the story in The Planetary Society's blog. Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell University

The Times received Opportunity's image with Bell's explanation and indeed accepted the "fudge," posting it along with more than 12,000 images from around the world. You can view Opportunity's work in this Update or by going to the revolving Earth graphic that is the center of this visual display, at the NYT site and mousing over Ithaca, New York. "It's really encouraging and delightful that there is this public feedback that people are still clearly following along with the rovers and interested in what they're doing. It was also wonderful that the New York Times editors were willing to accommodate our special circumstance," Bell told the MER Update last Friday.

After taking part in "A Moment in Time" and spending another couple of sols to recharge and bask in the winter Sun, Opportunity powered up and hit the Meridiani highway on Sol 2231(May 4, 2010), putting nearly 33 meters (108 feet) behind her. It doesn't sound like much and though it may seem that Opportunity was moving at a snail's pace, given the winter conditions those 33 meters were actually a good, solid average and about the limit of what was possible then. These rovers, fans know, could never be considered slackers.

As May marched on and Opportunity got closer to the winter solstice however, she became more constrained by power because her rover electronics module (REM) was registering dangerously low temperatures. "We've had to pay special attention to that and have been keeping the rover awake longer to make sure that module didn’t get too cold," said Callas. If the temperature inside the REM drops to -40 degrees Celsius or thereabout, two thermostatic, survival heaters automatically switch on. If that happened, Opportunity likely would be going nowhere because the heaters would draw so much power driving would probably be prohibited.

Still, Opportunity's main objective is to drive, so the thoughtful rover operators got creative and came up with something they call the 'lily pad' strategy, in essence, directing the rover to take solar energy solace after each drive on the northern side of one of the countless ripples rolling like sand waves of an imaginary ocean. By pulling up and perching at an ever so slight angle on the northern side of a ripple, the rover could position her solar arrays toward the Sun in the north and draw in a little more of the precious sunlight as she recharged her batteries. Lo and behold, the engineers' plan worked and increase power levels from less than 245 watt-hours to around 249 watt-hours.

Following another recharge session, Opportunity wrapped the first week of May with a 15-meter (49-foot) drive on Sol 2234 (May 7, 2010) coming to rest on another 'lily pad' or ripple. Despite the challenging conditions, the rover managed to log a total of 77 meters (252.6 feet) during the first week of May, bringing her odometer to 20,672.90 meters (20.67 kilometers, or 12.85 miles).

Endeavour in the distance

Endeavour in the distanceOpportunity took this black & white image of the Endeavour hills on the horison late this month, around May 26, using the panoramic camera (Pancam). The Pancam team at Cornell, led by Jim Bell, currently also The Planetary Society President, is working now to process a super resolution image, and will be releasing it in color in coming weeks, so stay tuned. In the meantime, for more on Opportunity's trek to Endeavour, check out: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / processed by Stuart Atkinson

Opportunity spent most of the second week of May hunkered down in place keeping her electronics warm and recharging. After a six-sol rest, the rover put the pedal to the metal on Sol 2240 (May 13, 2010) and drove for 25.95 meters, continuing the strategy of resting on the northern side of a ripple at the end of the drive.

The third week of the month saw Opportunity take another good long rest, but the 'lily pad' strategy started to really pay off. On Sol 2245 (May 18, 2010), the rover ripped and managed to put an impressive 55.5 meters behind her. Two sols later, Mars, it seemed, would reward the little robot field geologist by helping her increase her power.

Although the solar energy conditions are naturally expected to improve as the winter solstice passes, the planet whipped up a gust wind on or about Sol 2246 (May 20, 2010) that blew by Opportunity and whisked some of the accumulated dust from her arrays. "We don't really expect dust events during this time period," Banerdt reminded. "They're not unknown, though they are unusual in winter." "But we'll take them whenever they come," added Callas, noting that the event this month "really helped Opportunity." The event, in fact, resulted in an estimated 10% boost in energy, causing power levels to jump to 275 watt-hours.

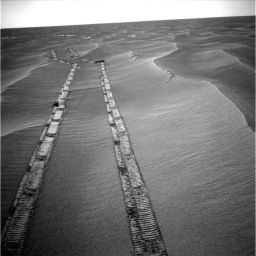

Opportunity looks back

Opportunity looks backOpportunity used its navigation camera to take this northward view of its tracks left by a drive from one energy-favorable position on the northern end of a sand ripple to another. The team calls this 'lily pad' strategy, because the rover is 'hopping' from one to the next, to take in as much sunlight fuel as possible. The rover snapped this picture from the northern end of a ripple, not visible in the image, on its Sol 2235 (May 8, 2010). It laid the tracks during a 14.87-meter (49-foot) drive southward on the preceding sol. For scale, the distance between the parallel wheel tracks is about 1 meter (3 feet). Mars' southern hemisphere was in the minimal sunshine period close to the winter solstice that occurred May 13, 2010 (Universal Time).Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

Best of all, the wind also cleared a bit more dust from Pancam's lenses. "We've had this problem in the right side in both fields of view, where you can see this darkening" [caused by the powdery fine Martian dust that infiltrated the camera system during the 200s global dust storm]," said Bell. "We've been seeing a slow clearing and a change in the dust in the front lens so that's improved over time. While we haven't taken all the test data we need to determine what percent improvement this event made, I do think when we do we will see improvement that will help us with mosaicking and won't have as many seams."

From the passing of winter solstice to the dust-clearing event, the rover seemed to be on something of a roll. And the very next sol – 2247 – Opportunity roved passed the Viking 1 Lander's longevity record of 116 days of surface operations and into the history books as the second longest-lived robot on Mars, second as far as we know to her twin, Spirit.

The celebration was delayed until last Tuesday, May 25, when most of the current MER engineers and scientists gathered in Pasadena for the annual team meeting slated for the next day at JPL. "We had a social event that was a sort of catchall for six years on Mars and to acknowledge that the rover is still going," said Callas. "What I think is really important though is not so much the longevity of the rovers on Mars, but how much they have done on the surface of Mars. These rovers have had a very active life and have been extremely productive."

Moreover, one might add, Spirit and Opportunity are not the kind of rovers content to rest on their laurels. On Sol 2252 (May 26, 2010), a reasonably revived Opportunity started her "engines" again and logged another 56 meters, then two sols later drove again.

Newfound energy seemed to be everywhere aroundthe MER mission in late May, especially among the crewmembers. After finalizing the plan to direct Opportunity to make landfall at the closet part of Endeavour's rim from the rover's position, and now that the rover can actually see her destination ahead, engineers and scientists alike are raring to go. The landfall location is, said Arvidson, "about 100 degrees azimuth from where we are, so it's a little bit south of the rover's current location." The high rim, which is clearly visible in the pictures of the Endeavour hills published last month is "about 133 degrees relative to where we are," he added.

The goal

The goalThis HiRISE image taken from orbit by the camera onboard MRO was shows the general area on Endeavour's rim where the MER team decided last week to direct Opportunity for arrival. From where the rover currently is, this is "the closest place on the rim," said Steve Squyres. "We're not wasting any time."Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA/ labeled by Stuart Atkinson

Although the general landfall location has been chosen, the precise spot is yet to be determined. "We haven't decided that level of detail yet," Squyres noted in an email earlier today. Choosing the closet part of the rim that juts out is, the principal investigator pointed out, in line with what Opportunity has always done. "Every time we've ever been in a situation like this we've always headed straight for the closet spot. That's what we did at the Columbia Hills. That's what we did when we rolled off the lander at Eagle Crater. We went straight to the closet spot on the outcrop," he pointed out. "We're going to do the same thing at Endeavour. It's a chance to find out what we're dealing with."

The landfall location has not yet officially been unofficially named, but the naming theme has been chosen, Squyres said. "At Victoria Crater, we named features along the crater rim after places that had been discovered and visited by Magellan during his circumnavigation of the globe." Victoria, as those following this mission know well, was one of Magellan's ships. "Well, Endeavour was one of James Cook's ships, so the places along the rim of Endeavour will be named after places discovered and explored by James Cook on his Endeavour expedition," he informed. And the spot where Opportunity will make first 'landfall' will receive one of those names, he added. A quick review of historical accounts indicates that Opportunity on arrival, and perhaps even as she gets nearer to her destination, will explore locations and targets nicknamed Tahiti, Huahine, Borabora, Raiatea, Sydney Cove, Botany Bay or Saint Helena. Time will tell.

This month Opportunity took a super resolution image of Endeavour's rim that should be released in living Martian color in a few weeks, said Bell. "We have the black and white version, but the one we've been showing the team is still incomplete," he said. "We've been having some processing issues, because of the dust changing on the front lenses, and the rest of the data just came down, so we're still working on it. Since we can actually do the super-res in color, I'd like to release that one. It takes us a few weeks to do the processing, because the images have to be combined and we have to work with the software, and then go through and manually fix what the software doesn't fix. But it is going to be a beautiful color shot."

While there is a lot of desire for Opportunity to get to Endeavour as soon as possible, the rover can only rove as fast as it can rove. Moreover, it will continue to take samples of bedrock, cobble, and craters along the way. One crater they're considering taking the time to check out is nicknamed Santa Maria. It's "a brand new crater" and will have exposed brand new material that "won't have any coatings" on the ejecta like the rover found on rocks lying outside Concepción Crater just a few months ago, said Arvidson.

Opportunity was scheduled to take another drive during this Memorial Day weekend, and now that the rover's gotten a little bump in power and this winter solstice is history, the hope is the rover will soon be back on track to drive every other day.

Chosen destination

Chosen destinationThis image includes some 23 different crops of a HiRISE image, taken from orbit by the camera onboard the Mars Reconnaisaance Orbiter that were stitched together. It is labeled to show the general area where the team now plans to have Opportunity make "landfall" at Endeavour Crater.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA/ processed by Stuart Atkinson

Better still, it looks now like she may have passed by the worst of the purgatoids, those threatening gnarly ripples. It was MER science team members – geologist Tim Parker, who played a critical role in landing site selection for MER and serves as the mission's geology team group lead; geologst Matt Golombek, a senior research scientist at JPL who also played an integral role in determining MER's landing sites and has frequently helped out in leading the SOWG science operations working group meetings; and Rob Sullivan, a senior research associate at Cornell – who took a look at HiRISE images last year and saw the significantly large ripples were along the rover's path. Together, they charted a new safer route that took Opportunity kind of counter-clockwise around the most threatening ones.

While the team had dubbed these rover-threatening obstacles after the infamous Purgatory Dune, "with slopes less than 15 degrees they are not really dunes but ripples," Arvidson clarified. In any case, ripples or dunes, either way any one could probably have stopped Opportunity in her tracks just like Purgatory Dune did. After following the newly charted path, it should be" easier to go sailing as we rove forward," said Callas.

"I'm always reluctant to declare victory on something like this, because funny things can get you," said Squyres cautiously. "But the orbital images do suggest that the driving is going to get progressively easier as we approach the rim. We have made the big left turn and we're starting to head mostly to the east now, which is nice. We've been heading south for a long time." Though Opportunity will continue to jog here and there to avoid danger and the operations team will do "whatever we need to do" to keep the rover safe, "we have rounded the corner and are heading for our destination," he said.

"As we move to southeast and east the ripples will get smaller and lower, but there are still some big ripples and so there are still issues," Arvidson added, not the least of which is the fact that Opportunity will soon begin crossing ripples to get to her destination. "One of the discussions in our meeting this month was about the best practices for crossing the ripples. The western side is softer, which we learned on Purgatory when we got all the wheels stuck. Likewise, there was a minor event on Sol 2220 where we failed a slip check and it looked like we had taken too shallow an attack and the RPs [rover planners] have formulated a best practices for climbing the ripples. The good news is it'll just take some time to get through the next couple of kilometers, and then it will be like the drive between Eagle and Endurance, smooth going," he said.

Opportunity and the MER seem fully amped and up for the challenge of the long trek ahead, no matter what it may entail. In part, no doubt, that's because the end of this road promises riches beyond those that the rover has already gathered. "Endeavour is compositionally different from anything we've seen before with this rover, and there is now clear and compelling evidence for clay minerals in the rim of this crater as seen from orbit," Squyres summed up. "That makes it a very, very interesting place. Clay minerals form under wet conditions more neutral pH than the wet, acidic environment that formed the sulfates we've found with Opportunity," he explained. There are ancient rocks, older than we have ever seen. It's going to be like a whole new mission when we get there."

While Opportunity has been roving along remarkably well given her age and the brutal climatic conditions of late, the rover still has a long way to go to get to Endeavour's rim, which lies an estimated 11-to-12 kilometers (6.8-to-7.4 miles) away. But hope remains high and no one is slowing down, despite the fact that everyone has to acknowledge the end could come, theoretically anyway, at any time. "We have no idea how long this rover is going to last," said Squyres.. "So we're not going to take the long route. We're going to go to the first jut of stuff we can find. Then, having done that, we can talk about going other places too."

On The Beach

On The BeachArt meets science in this downloadable little poster, titled On The Beach. It come to you here courtesy of rover poet Stuart Atkinson and MER image enhancer Astro0. Both are members of UnmannedSpaceflight.com. Enjoy. For more of Atkinson's MER poetry and prcoessed or enhanced pictures, go to: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.comCredit: Poem by Stuart Atkinson UMSF.com; photo courtesy NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / enhanced by Astro0

* Editor's Note: The record for longest working lifetime by a spacecraft at Mars belongs to NASA's Mars Global Surveyor, which aerobraked into orbit in 1997 and operated for more than 9 years. Mars Odyssey, which has been in orbit since in 2001, has been working at Mars longer than any other current mission and is on track to take the orbiter longevity record from MGS late this year.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth