A.J.S. Rayl • May 31, 2009

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Spirit Sand Snared and Dusted, Opportunity Rests and Roves

The Mars Exploration Rovers hit some rough patches in May – as Spirit sat stuck in a sand patch all month and Opportunity had to stop again to rest its right front wheel – but with a little help from Mars, the intrepid, twin robot field geologists cruised through the summer solstice with the energy and invincibility of a couple of teenage robots.

Mars virtually dusted Spirit and for the first time in years this rover is bursting with energy, snapping pictures like a tourist, and waiting on its ground crew to give it instructions on how to extricate itself from the sand that first snared it in April.

On the other side of the planet, Opportunity, which lucked into finding another possible meteorite this month during its rest stop, is back to roving on toward Endeavour Crater, the impact depression that is some 20 times larger than the one that made Victoria Crater and still a some 13-kilometer (8-mile) drive away.

At Gusev Crater, May was the worst of times and the best of times for Spirit. It was the 'best of times,' because, for starters, the rover remembered everything. It seemed to be back to its old self, over the anomalous behavior of last month, the episodes of amnesia, spontaneous resets, and oversleeping and missing work. "None of these events have recurred," said Jake Matijevic, the chief rover engineer, who was a part of the original design team. What happened to the rover last month remains a mystery. "It's kind of strange," he said. "I haven't found a good explanation for what happened or why."

It was also the 'worst of times,' because one thing Spirit got to remember was that it was effectively stuck in one place the entire month. The rover had been trying to get up a rise or 'lip' to get onto what appeared to be more solid ground to make headway to the south and Goddard and von Braun, the house-sized pit and mound that are its next destinations. "We apparently broke through a crust of harder material that covered the sand," said Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis, the deputy principal investigator for MER science, who generally oversees science operation on this rover. "As soon as that happened, it just started churning into this loose material and we haven't moved since."

There wasn't "any appreciable change" in Spirit's position since the middle of April, confirmed Matijevic. "Even though it was only a little bit of a rise, Spirit has real difficulty whenever we encounter these in the terrain because of its broken right front wheel," he explained. Once Spirit cracked the crusty covering and its left wheels hit the sand, it began doing more to dig itself in than out. "So we basically stopped driving," he said.

Squeaky clean

Squeaky cleanSpirit took this picture of its solar array with its panoramic camera (Pancam)on Sol 1907 (May 15, 2009). It's hard to believe but the rover got even a little cleaner as the month progressed and its power levels shot back up to where they were back toward the beginning of the mission.

Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell University

During its last attempt to move early in May, Spirit experienced a stall in the left middle wheel, something that had to be checked out. There was some concern that the rover's belly might be on some rocks, reason enough for the rover to stand down and wait for the engineers on the ground to do a drive assessment and evaluation.

Things were looking gloomy as May took hold, but the first diagnostic test on Spirit's left middle wheel turned up nothing untoward. Even so, "may be weeks" before the rover moves again, announced John Callas, MER project manager, in an official statement mid-month from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where the rovers were designed and built, and from which they are commanded.

"When this first happened, there were a few days there where it just wasn't clear how we were going to tackle this and there was a kind of unease that came over the team," said Steve Squyres, of Cornell, the principal investigator for MER science. "I think the unease came from the fact that the power was pretty bad when this first happened and we were scared we wouldn't have the time to work the problem right and that we would have to take some risks."

Then, Mars came to the rescue, blowing "kisses" of wind to the rover all month long. "We went down the west side of Home Plate with the hopes that being out in the open, out in the plains like it is, the rover would catch some wind gusts and it has," Squyres said. "The summer season, the dust devils and their high velocities, and these vortices just cleared the panels off," added Arvidson. "This is what we were hoping for and we finally got it."

It was, as it turned out, way more than they had hoped for. Heading into this weekend, Spirit was boasting a jaw-dropping 840 watt-hours, almost as much energy as it had after landing in the southern hemisphere Martian summer of 2004. "We were close to 960 watt-hours or so early on when the tau [level of dust in the atmosphere] was near 1," said Matijevic. That amount of dust is significant, but not overwhelming or unexpected for the Martian summertime. "Obviously it's been a long time since we've been at this energy level. The rover is essentially like another vehicle. The winds have sort of recreated the original Spirit capabilities."

"We have so much power," Squyres added, "it's ridiculous. Spirit is as clean as it can get."

For the first time in a long, long time, noted Arvidson, "Spirit is only limited right now by data volume and how much we can get down to Earth, to keep from filling its flash memory up."

Surround sand

Surround sandSpirit took this image on its Sol 1914 (May 22, 2009) with its panoramic camera (Pancam) and the team rendered it in false color to better delineate the geology around the rover. The photograph gives some idea of the tenacious and tricky terrain through which the rover is trying to negotiate.Credit: NAA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

All this newfound power translated into a change of pace that for Spirit that has been "enormous," said Matijevic. "We've gone from struggling to find energy for activities to 5 hours at least during the daytime and we're conducting some nighttime observations again, and communicating in both the morning and evening with Mars Odyssey." A doubling of downlink sessions with the obiter will help ease a backlog load of data onboard Spirit and also insure that the soil pictures needed for the rover team to devise an exit strategy are sent home promptly.

Although Mars is a pretty busy place these days, Odyssey, the unsung, workhorse orbiter, and its team graciously put Spirit back into the schedule. No one expected the MERs to be roving five and a half years after landing, but since the twins are going still, they are amongst the community of planetary explorers deemed robot royalty.

Perhaps the best thing about being flush with power is that neither Spirit nor the team has to hurry to find a winter haven. "It buys us time to work our way methodically through this problem instead of having to rush it and that is what's we're doing," said Squyres.

"November is no longer the time we need to be parked facing north [so Spirit can tilt its solar arrays and survive another winter] – unless a whole lot of dist accumulates between now and then," elaborated Arvidson.

The team will use the time to plan the next steps "carefully," said Callas. "We know that dust storms could return anytime, although the skies are currently clear."

Engineers and scientists alike spent a good deal of May mixing up analogue soils in preparation for ground testing and devising exit strategies. "The whole team has gone into problem-solving mode and that's something we're good at," Squyres said. "We're working our way through it."

Snared

SnaredDuring attempts to extricate itself from a patch of sand over a period of about two and a half weeks from April into May, Spirit made little progress. By Sol 1899 (May 6, 2009), it had succeeded in partially burying some of its wheels. The rover took this image with its front hazard-avoidance camera on Sol 1899, the day when the team temporarily suspended driving attempts. The ground crew is now studying the ground around Spirit and planning simulation tests of driving options with a test rover at JPL. Driving attempts between the time Spirit took a similar image 10 sols earlier [seebelow] and when it took this image moved the rover a total of about 36 centimeters (14 inches).

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

They're only waiting now on the JPL indoor Mars yard or "sandbox" to be restored. A disc drive failure on an interface system used to run the surface system test bed (SSTB) rover used in the sandbox effectively zapped any ground testing plans for awhile, Matijevic confirmed. Where any other team might fall from frustrating exhaustion, for the MER team, this latest snafu just keeps things interesting. The plan now is to begin basic testing on the SSTB Light rover next week. One of the first rovers used for early mobility tests, the SSTB Light is stripped down or not fully loaded and so is not a MER clone.

With luck, the regular SSTB rover will be back in action soon. "We need to have that test bed all together to simulate 5 or 6 different ways of getting out, so we can chose the one that is most likely of popping us out of the current situation," explained Arvidson.

Spirit meanwhile is keeping busy, taking a new color panorama with its panoramic camera (Pancam) and a whole lot of images with all its cameras of the sand that's giving it so much trouble. At first blush, the light-toned soil it's churned up looks a little like the silica it's found all around Home Plate. "But we don't know what it is," said Arvidson. "It could be silica or sulfate, but it's sandy for sure."

This weekend, Spirit is scheduled to extend its instrument deployment device (IDD) and reach underneath its belly and snap a picture with the microscopic imager (MI) camera that's on the end of its arm. "We've used that trick now a couple of times and we'll use it again now on Spirit to see what's going on under the vehicle," said Squyres, who suggested it.

They had Opportunity rehearse the gymnastic motion earlier this month and it worked far better than many anticipated. Although the MI camera, which focuses on thing close-up, is not designed to take this kind of snapshot picture, and although the image Opportunity took was fuzzy, it clearly showed the left middle wheel. And that was something to see, especially from that angle. "I haven't seen that middle wheel like that since Cape Canaveral," marveled Squyres.

Once Spirit does extricate itself from the sand, the objective is still to head south to Goddard and von Braun. "We're continuing south, because that's where the action is," said Arvidson. And, he added: "Don't give up on this rover."

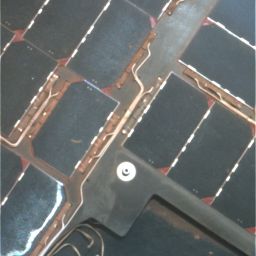

Looking underneath

Looking underneathSimilar to a geologist's hand lens, the microscopic imager on the Mars Exploration Rovers (MER) is designed to image objects at a close distance (less than a few centimeters) at very high resolution. On Sol 1890 (May 18, 2009), Opportunity stretched out its arm and reached underneath with its MI camera and took a picture of its underside. Although out of focus, which was anticipated for this distance, the image does show the rover wheels (left middle and left rear), the ground and the underbelly of the rover. "I haven't seen the middle wheel like this since Cape Canaveral," enthused Steve Squyres. This picture may prove helpful for getting Spirit out of th mess it's in. Spirit was commanded to take a similar image this weekend.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Opportunity

Over at Meridiani Planum, Opportunity continued on its long trek to Endeavour Crater, but it began having an issue with elevated current in the motor to its right front wheel again. "It's been a persistent problem," said Matijevic. "We saw evidence of this way back even on our drive to Victoria Crater and subsequent to that as well. We've been trying to recondition or reset it if we can by driving backwards. This reverse direction ought to redistribute the lubricant in the wheel, but it doesn't always do it completely, so the other strategy is to stop and let it rest."

There is natural concern over the persistence of this problem, because this is similar to what Spirit experienced years ago just before its right front steering wheel broke and froze in place, turning into a kind of anchor. This month, the team decided to err on the side of concern. Opportunity stopped to rest its wheel again.

It just so happened that this lucky rover was in a choice place to pause. The science team had been eyeing some intriguing little pebbles in the area and decided that a comparison of the pebbles and nearby cobbles would be a strong addition to the systematic study of rocks and soils en route to Endeavour. As Opportunity rested its wheel, it attempted to take a close up look at three of the pebbles then moved onto a cobble they called Kasos. The pebbles and cobbles didn't appear to be from different sources, according to Albert Yen, of JPL, a MER science team member. Kasos, he said, may well be another meteorite.

As May progressed, Opportunity roved to a Memorial Day for the history books. On Sol 1897 (May 25, 2009), the rover made another "giant rove" for roverkind, pushing its odometer past 16,133.96 meters – passing the 10-mile mark. "That was cool," reflected Squyres. Especially when one considers that the distance requirement for mission success was 600 meters and that the rovers were "warrantied" to drive as much as one kilometer over their lifetimes. "We've exceeded that by a factor of 16 now," he pointed out.

Since leaving Victoria Crater about eight months ago, Opportunity has driven about one-fifth the way to Endeavour by the route chosen. The objective for June remains the same: "Drive. Drive. Dirve," said Squyres.

Rove on, Opportunity

Rove on, OpportunityThis rendered image of Opportunity is an image produced using "Virtual Presence in Space" technology, developed at JPL. It combines a photorealistic model of the rover and a false-color mosaic taken by the rover on Sol 134 (June 9, 2004) with its panoramic camera (Pancam) while in Endurance Crater. The rover has roved a long, long ay since then.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell; MER model Dan Maas, synthetic image by Zareh Gorjian, Koji Kuramura, Mike Stetson and Eric M. De Jong.

Despite still elevated currents to its right front wheel, Matijevic said Opportunity will continue to drive both forward and backward. "We're just keeping an eye on it," added Squyres. "We'll drive as far as we can without stressing the wheel too much."

The attempts to shake the dust out and off of the optics in the miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES) never worked. The dust was deposited during the global dust storm of 2007 and the optics have been obscured ever since. Now the team has decided to open the instrument's cover to see if Mars might take care of the situation.

"The project has decided to move on to a different dust mitigation approach – letting the wind blow the dust off, confirmed Amy Treuba Knudson, an associate research scientist at the Planetary Science Institute, who is overseeing the Mini-TES science on Opportunity. "We have adjusted the way that we plan to open the Mini-TES mirror shroud a few times and now we are waiting for final approval before we try it on Mars."

It may be that they go for blow in June. "We've played every other card we've got, so this is the last one," said Squyres.

Both Spirit and Opportunity, which landed during the planet's southern hemisphere summer in 2004, marked their sixth Martian summer solstice on May 21. Worthy of a roverrita toast it would seem. The twins also passed their physicals with flying colors in May, as each continued to work daily.

The robot field geologists are both sporting robust energy, although Opportunity’s power levels of around 450 watt-hours now seem almost paltry compared to Spirit's bounty of 800+ watt-hours. But, Opportunity's levels are "understandable" and there's no cause for concern, said Matijevic. "Since Opportunity is very near the equator and the Sun is toward the south, overhead at 25-degrees south, there's a fairly good size loss angle for the arrays, which are basically flat. The rover's power will increase as we keep going through the summer season."

In other MER news, a paper on Opportunity’s exploration of Victoria Crater, written by Squyres and 33 other MER science team members, was published in the May 22 issue of the journal Science. Since landing in 2004, this rover found a compelling saga of environmental changes that occurred over billions of years.

Opportunity spent nearly two Earth years -- from September 2006 through August 2008 – surveying the rim and interior of Victoria Crater and its findings there reinforced and expanded on what the scientists learned from the rover’s explorations of the smaller craters, Eagle and Endurance earlier in the mission.

A rock from space blasted a hole about 600 meters (2,000 feet) wide and 125 meters (400 feet) deep that is now Victoria Crater, the authors theorize. But wind erosion chewed at the edges of the hole and partially refilled it, increasing the diameter by about 25%, as evidenced by its scalloped edge, and reducing the depth by about 40%. Steep cliffs and gentler alcoves alternate around the edge of the bowl that is now about 0.8 kilometers (half-mile) in diameter.

In documenting the effects of wind and water, Opportunity found that water repeatedly came and left billions of years ago, while the wind persisted much longer, heaping sand into dunes between ancient water episodes. Interestingly, Squyres and his co-authors noted, these patterns still shape the landscape today.

As Opportunity photographed the crater's rim and interior, it inspected layers in the cliffs around the big bowl, including layered stacks more than 10 meters (30 feet) thick. "What drew us to Victoria Crater is the thick cross-section of rock layers exposed there," Squyres said. "The impact that excavated the crater millions of years ago provided a golden opportunity, and the durability of the rover enabled us to take advantage of it."

Opportunity ready to roll

Opportunity ready to rollThis image shows a simulated Opportunity ready to descend into Victoria Crater via the rock-paved slopes of the alcove Duck Bay. Inside the crater, the rover examined the deeper, older rocks and discovered another chapter in a compelling saga of environmental changes. Duck Bay has slopes of about 15 to 20 degrees and exposed bedrock, which made it the safest site for entry.

Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell University

The distinctive patterns Opportunity saw indicate the rocks formed from shifting dunes that later hardened into sandstone, the authors write. The rover's first observations showed interaction of volcanic rock with acidic water to produce sulfate salts. Dry sand rich in these salts blew into dunes. Under the influence of water, the dunes hardened to sandstone. Further alteration by water produced iron-rich small spheres, or spherules, that the team nicknamed "blueberries" when the rover first saw them in 2004, as well as mineral changes, and angular pores left when crystals dissolved away.

With the instruments on its IDD, Opportunity studied the composition and detailed texture of rocks just outside the crater, as well as exposed layers in the ‘alcove’ dubbed Duck Bay. The rocks the rover found beside the crater include pieces of a meteorite, which may have been part of the impacting space rock that made the crater.

Other rocks on the rim of the crater, the authors suggest, were excavated from deep within it when the object hit. These rocks bear the iron-rich spherules or blueberries, which, like concretions on Earth, formed from interaction with water penetrating the rocks. The spherules in rocks deeper in the crater are larger than those in overlying layers, suggesting the action of groundwater was more intense at greater depth. Inside the crater at Duck Bay, Opportunity found that, in some ways, the lower layers differ from overlying ones, revealing less sulfur and iron, more aluminum and silicon. This composition matches patterns the rover found earlier at the smaller Endurance Crater, about 6 kilometers (4 miles) away from Victoria, indicating the processes that varied the environmental conditions recorded in the rocks were regional.

As May turns to June, the rovers rove on as the science continues to stream down from Mars.

Spirit From Gusev Crater

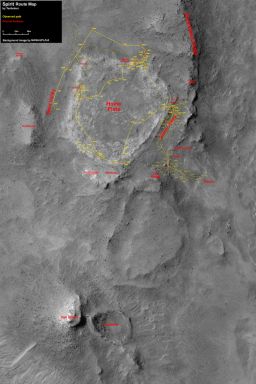

Spirit route map

Spirit route mapThis image taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter has been labeled by Eduardo Tesheiner, an active participant on UnmannedSpaceflight.com, to show Spirit's route from its arrival in the Home Plate area on Sol 743 through Sol 1871 (April 8, 2009), when the rover began suffering a series of bouts with 'amnesia.' Credit: NASA / University of Arizona /E. Tesheiner

Spirit bounded into May with the blessing of a wind gust late in April that pushed its power levels to 370 watt-hours. That's more that this rover had had in at least a year and a half.

Happily, the rover also suffered no recurrence of any of the anomalous behavior that happened last month between Sol 1872 and Sol 1881 (April 9 and April 18, 2009) – no amnesia or resets or oversleeping and missing work. The behavior continues to mystify Matijevic and other rover engineers and there is still no explanation for the April anomalies.

The MER team implemented planned changes to the rover's wake-sleep cycle and internal data logging, as well as set up a new ability to detect amnesia events, all in anticipation of one or more of those anomalies happening again, Matijevic said. But Spirit didn't miss a beat this month, leaving the investigation to stall.

Spirit was having trouble however with the terrain on the west side of Home Plate, particularly the loose sand that it first encountered in April while trying to rove up a little rise to get on a more firm path for driving south to Goddard and Von Braun, its next destinations. The rover's left wheels apparently broke through a crusty covering and hit the sand patch. With only five driving wheels, it was painfully slow going for the rover during the first week of May, as it tried again and again to back out of the Martian ‘quick sand’ that first snared it in mid-April. Success was elusive and progress was measured in centimeters.

As it turned out, Spirit’s wheels slipped so repeatedly that by Sol 1899 (May 6, 2009), its left wheels became partially buried, up to mid-hubcap so to speak. With every commanded move, the rover seemed to spin its wheels deeper. "In trying to move in this area, the underlying material got churned up and turned over around the wheels," said Matijevic. That was frustrating for the rover drivers. "Typically, these drivers plan a drive not just to make a small motion of a few centimeters, but to do a complete extraction and make progress along the planned path through the area." In other words, they make plans to drive this rover.

Although Spirit's right front wheel is not immediately involved in this latest event, its broken state matters. With the MERs, there is, "a means by which one side or the other can sort of compensate for problems that one wheel is encountering when it's on difficult parts of the terrain," Matijevic explained. Not being able to utilize Spirit's right front wheel makes the right side less capable of being able to compensate. That makes for a kind of "double whammy" dilemma for Spirit, he said. Worse, during the last attempt to exit the sandy patch, the rover suffered a stall in the motor to its left middle wheel. That had to be checked before the rover did anything else.

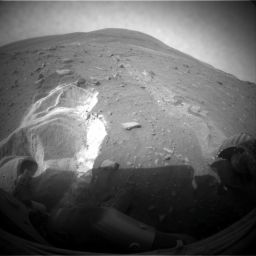

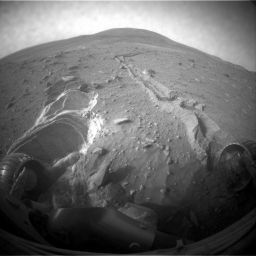

Snared by sand

Snared by sandSpirit slipped in soft ground during short backward drives on its Sols 1886 and 1889 (April 23 and 26, 2009). It used its front hazard-avoidance camera after driving on Sol 1889 to get this wide-angle view, which shows the soil disturbed by the drives. This view is looking northward, with Husband Hill on the horizon. For scale, the distance between the wheel tracks is about 1 meter (40 inches). It drove 1.11 meters (3.6 feet) on that sol, after roving for 1.68 meters (5.5 feet) on Sol 1886. Spirit lost the use of its right front wheel years ago and now drives mostly backward dragging gthe wheel like an anchor. As May dawned, the rover dug its left wheels in deeper and was only making only centimeters' worth of progress in the sandy soil.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

All the slippage, plus the possibility of the left middle wheel being jammed or, perhaps, Spirit being high-centered – in other words, its belly stuck on a rock – made the team's decision to temporarily suspend driving easy. As of Sol 1900 (May 7, 2009), Spirit was commanded to stay put and begin extensive remote sensing observations, taking tons of pictures of the sand and soil characteristics, so the engineers and scientists could figure out exactly what they were dealing with.

Back on Mars, Spirit was getting its solar arrays further dusted as Martian winds continued to blow across the Gusev region. By the second week of May, the rover's power production had jumped up to a rich 650 watt-hours. For the first time in a very long time, Spirit had more energy than Opportunity.

With the significant improvement in power, Spirit could once again downlink data via morning UHF relay passes with Mars Odyssey, as well as during its standard evening communication session with the orbiter. The Odyssey team made a special effort to add Spirit back into the relay line-up and the rover subsequently began sending home some of the backlog of onboard data, as well as all the current sandy soil pictures and engineering data on its ground geometry.

Both Spirit and its ground crew spent what ultimately would be the rest of May working on the diagnostics for the rover's left middle wheel, refining the analogue Martian soils, and planning exit strategies. A "shoebox" test of a soil simulant, called Bag House dust, which actually is ground-up basaltic cinder, was planned to be performed under one wheel of the SSTB rover to see if the simulant exhibits the characteristics of the soil on Mars.

Meanwhile, on Sol 1908 (May 16, 2009), engineers took Spirit through a low-voltage continuity test of the motor of its left middle wheel. The results showed normal resistance for a healthy motor. The wheel, alas, appeared to be fine. Even though very small voltages were used in that test, the engineers could see a tiny amount of motion, less than a degree, opposite of the apparent jam on Sol 1899 (May 6, 2009). Since it was likely caused by the unwinding or relaxation of the strain in the gearbox, it was a good thing to see because the motion meant it was less likely there is a jam."

“This is not a full exoneration of the wheel, but it is encouraging," Callas reported. "We're taking incremental steps. Next, we'll command that wheel to rotate a degree or two. The other wheels will be kept motionless, so this is not expected to alter the position of the vehicle."

Spirit conducted that next test with a small, 4-degree backward wheel motion on Sol 1913 (May 21, 2009). Again, everything seemed was A-okay. Last week, it conducted a 16-degree backward wheel motion test to investigate the wheel further and no problems or issues of any kind were detected, Matijevic said.

"We ran a set of diagnostics, which basically indicated that by turning the wheel backward in the reverse direction as we were turning it during the drive, we have in effect released whatever had been the cause of the stall condition," he said. "There is nothing wrong with the motor and nothing is stuck in the wheel as far as we can tell."

The team, meanwhile, had also enlisted other spacecraft at Mars to help free Spirit. For example, Opportunity, tested a couple of picture-taking procedures – reaching around with its IDD to use the MI camera on the end to take a picture of the wheels, then on Sol 1911 (May 18, 2009) it reached underneath itself and snapped a picture of the wheels. It worked. The image was blurry, but you could clearly see the wheels. This would be a way for Spirit to see whether something was obviously wrong with the left middle wheel and/or if its belly was stuck on a rock.

While the team members prepared to begin ground testing the Bag House dust analogue sand with the SSTB rover in the indoor Mars yard or sandbox, one of the systems went down when a disc drive failed and all ground testing got put on hold. "There is an interface computing system that is provided for the computer onboard the test vehicle and that machine actually serves as the representation of the ground data system for our flight systems here," Matijevic explained. "It senses the collection point for data that is processed and developed as telemetry on the test vehicle and it also is a kind of depository for certain scripts and set-up sequences that we use to get the vehicle to drive and conduct various other major functions."

Although the system is backed up, "it's not backed up frequently," said Matijevic. There was "a fair amount of information" that was lost as a consequence of the disc drive failure that took place on that machine, he added. "Part of the delay here is to get another machine and disc drive and other equipment in place."

Simulating Mars on Earth

Simulating Mars on EarthWorkers at JPL started digging in the indoor Mars yard in May. The objective is to replicate Spirit's situation on Mars. To do that, the rover has been taking images of soil properties and ground geometry and sending the data back to Earth where MER team members are using that data and other information to construct a simulation of Spirit's situation. They have spent the last couple of weeks testing different materials to use as soil that will mimic the physical properties of the Martian soil where Spirit is embedded. Then, team members will experiment with five different strategies and techniques the rover might use to get out of the trap. The plan is to select the one that works best. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

So, as the third week of May began, Spirit was all revved up, with no command to go. The summer winds had continued to blow and the rover was benefiting big time, rocked and buffeted by a stream of gusts, ranging from what must have been menacing, whirling vortices to more gentle whisky breezes.

Although they have documented at least three dramatic dust-clearing events, during the intervening periods between these major windy episodes, "there have been daily, continuing cleaning activities," Matijevic pointed out. All told, the Martian winds have taken one filthy rover and made it clean again, thus making this May – or Martian summer – one for the books.

"On this side of Home Plate, we've got this wonderful smooth plains, lowlands off to the west of us, and we're not in the wind shadow of Home Plate anymore – plus This is the time of year when we've always had cleaning events," reminded Squyres. "If you went up there with Windex and a rag, you could make it a little cleaner, but not much. We're well over 800 watt-hours and that's just crazy."

There were also other contributing factors to the increased array performance, Matijevic said, the low tau or level of dust in the atmosphere and the overhead position of the Sun among them. In addition, he said: "We've been seeing what I would call a stabilized dust factor value, which under the circumstances of this low tau and these summer conditions probably means that whatever has been deposited has been removed and continues to be removed over the course of the last month. During the last Martian winter, we were down to .3, where no more than 30% of the light was coming through the panels. We're up now to .78." Which means that 78% of the sunlight hitting the solar panels is being converted to energy.

No matter how it happened, the team is stoked. Spirit is producing 840+ watt-hours as May comes to an end, something that has made some crewmembers as well as rover fans giddy.

With all this energy, Spirit has to work. "The consumables we have in any given sol for planning are power and time, which kind of go together, and data volume," said Arvidson. "Right now we're not limited at all by power. We're limited by data volume and how much we can get down [to Earth], to keep from filling the flash memory up. We're beginning to think about power-hungry but data limited kinds of operations, like waking up in the nighttime hours or running the APXS or the Mössbauer spectrometer overnight."

Driving in West Valley

Driving in West ValleyBack when the roving was easier in the West Valley, Spirit drove 6.98 meters (22.9 feet) southeastward on its Sol 1871 (April 8, 2009), then captured this view looking at the ground covered with its front hazard-avoidance camera. For scale, the distance between the parallel wheel tracks is about 1 meter (40 inches). Although Home Plate is not within this image, the hill on the horizon in the upper right is Husband Hill, the summit of which is about 750 meters (nearly half a mile) to the north of Spirit's position. It was following this drive that Spirit exhibited anamolous behavior.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

During the past week, Spirit has worked away taking the hundreds of images needed for a new panorama. "We're taking a beautiful panorama that will include the deck and a nice clean rover," said Squyres.

It's also taking dozens of pictures of the soil and sand in which it's presently a bit mired, with its hazard and navigation cameras, as well as the Pancam and MI, for both engineering and science use. "We're basically doing a very good job of documenting the site," Matijevic offered. "Many of the observations that we've been doing and checking off are planned observations made or talked about by the science team when we entered into this West Valley about two months ago."

Far and away, the best thing about all this newfound energy though is that Spirit doesn't have to hurry to find a winter haven. "It buys us a lot of time," said Squyres.

"If we were still down to 250-300 watt-hours, we would have to rush through this ground testing process, because winter is coming and we would be in a bad way," he continued. "Now, we've got plenty of time to experiment on Earth and get it right. There's no reason to try anything rash on Mars. And now that we have the power, we really have gotten engaged in solving the problem. The real action right now is on the ground," he said. Or will be soon anyway.

If everything goes as planned, the team will begin basic ground testing for the Spirit extraction this coming week with the SSTB Light, one of the early, no-payload rovers used for mobility testing. Then, as soon as the regular SSTB rover is back in action, the final testing on exit plans will be done.

"We have five different hypotheses as to the best way to get out," said Arvidson. "Although we can't exactly replicate the material properties of the Mars soils, we can get close and we have the right topography, so we will conduct a differential study on which of the five strategies has the highest probability of popping us out of there."

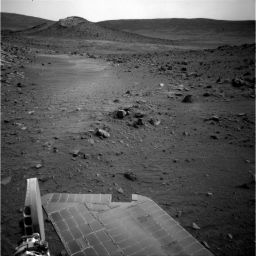

Eyes on the prize

Eyes on the prizeAfter driving in West Valley in early April 2009, Spirit used its navigation camera to capture this view of the terrain to the southeast. The mound on the horizon in the upper left is von Braun, one of the rover's next attractions.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

This weekend, Spirit was slated to reach with its arm and underneath its belly and take pictures of what it sees. Right now, the team doesn't know if anything other than the sand is hanging up Spirit.

From the images returned so far, the light-toned sand looks like the silica the rover has found all around Home Plate. "But we don't know really what it is," said Arvidson. "It appears to be poorly sorted sand," he said. "You can actually see chunks in the Pancam images It's not dust. It could be silica and it could be sulfate. We'll find out."

When Spirit looked at the light-toned and regular dark rusty soil with its Mini-TES, it found little difference thermally between the two, Arvidson noted. "But silica and sulfur tend to go together. In Arad, for example, back in the Inner Basin, silica and sulfur were both enhanced." In coming sols, Arvidson and other science team members will be looking closely into the composition of the sand and soil.

Once the ground testing is done and the team has chosen an exit strategy or two for Spirit, the rover will probably be ready to move, Matijevic said. It's odometer, for now, remains at 7,729.93 (4.80 miles).

"We're not really stuck," said Arvidson. "The last drive actually moved the vehicle, but that's when the middle left wheel stalled, so we stopped to do those diagnostics," he reminded. Matijevic agreed: "If the vehicle could extract itself on the order of 10 centimeters or so up from the holes it's dug on the left side, then there's a good chance it would be back on a kind of terrain that will allow it to proceed away from this area."

The bottom line right now, said Arvidson, is a lesson learned from the MER mission: "Don't give up on this rover."

opportunity from meridiani planum

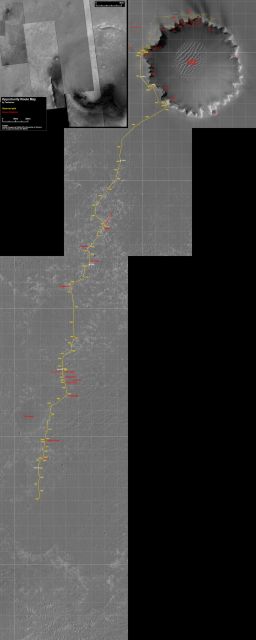

Opportunity route map

Opportunity route mapThis image, taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) was labeled by Eduardo Tesheiner to chronicle Opportunity's route from Victoria Crater to where the rover was on Sol 1900 (May 28, 2009, on its journey to Endeavour.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / E. Tesheiner

Opportunity roved into May after skirting a troublesome ripple on Sol 1872 (April 30, 2009) and getting another respectable 42 meters (138 feet) closer to Endeavour Crater. Since that final drive of April saw the electrical current levels in the right-front wheel rise higher than normal levels again, however, the rover’s first drive of May, on Sol 1873 (May 1, 2009), was a backward one, covering about 50 meters (164 feet).

It was back in March that Opportunity first began experiencing the most recent elevated wheel current issues in February. Although the team knows that rest and backward driving will help redistribute the lubricant in the wheel, the undeniable reality is that this is a sign of aging and for the rambunctious rover it was anything but welcome. "The reason there is a general level of concern about this is that we had the same issue with the right front actuator on Spirit before it failed, and we're a long way from pulling up to Endeavour Crater," said Matijevic.

Erring on the side of concern, the team decided to have the rover take another rest and check out some more rocks as part of its systematic study of rocks and soil on the long journey to the big crater. As Opportunity's luck would have it, the rover was right on an exposed rock outcrop that featured some interesting pebbles. Science team members decided to conduct a science campaign comparing and contrasting the pebbles with nearby cobbles.

On Sol 1877 (May 5, 2009), Opportunity “bumped” into position to move close to some chosen pebbles, which it planned to check out with the instruments on its IDD, while resting its wheel. "One of the goals was to determine if the smaller rocks (pebbles) had the same composition as the larger rocks (cobbles)," explained Albert Yen, of JPL, a MER science team member. The rover moved in with its alpha-particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) on a pebble dubbed Tilos first.

During the second week of May, in the midst the pebble study, Opportunity took a special picture on Sol 1881 (May 9, 2009) with the MI, which is mounted on the end of its arm. It reached around and took an image of its left-front wheel to see if it made sense for its twin, Spirit, to try and do the same thing in order to get a better idea of the status of that wheel in the sand. The image, though blurry, did show the wheel.

Opportunity then positioned its APXS on a second pebble named Kos for an overnight integration. On the next sol, it moved its APXS to a new pebble, Rhodes, to try and analyze its composition. "We faced a number of challenges associated with positioning the APXS on these very small targets and ended up with a larger than desired standoff distance," Yen explained. That acknowledged, he added: "I believe that we did the experiment well enough to determine that these pebbles do not have large concentrations of nickel (Ni), a meteoritic tracer, but the uncertainty is significant because the positioning was less than ideal."

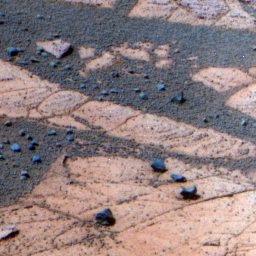

Pausing for pebbles

Pausing for pebblesThis Pancam image, rendered in false color by the team at Cornell, shows a scattering of the pebbles Opportunity attempted to analyze in-depth with the instruments on its instrument deployment device (IDD) this month. Although the rover had a difficult time adequately placing its alpha-particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) on the tiny targets, the population of pebbles, according to Albert Yen, MER science team member from JPL, "appears to be from a different source from the cobbles." The rover snapped this image on its Sol 1882 (May 10, 2009).

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

The second part of the experiment in comparing the pebbles to the cobbles was to drive over and analyze the cobble. On Sol 1884 (May 12, 2009), its work on the pebbles done, Opportunity backed away from the tiny targets and roved about 6 meters (20 feet) into a new position to analyze a cobble called Kasos, Yen said.

Opportunity put its APXS on Kasos to determine its mix of minerals on Sol 1886 (May 14, 2009) and the next sol placed its Mössbauer spectrometer on the cobble for a multi-sol integration. When the observations were analyzed, Kasos was pegged as another probable meteorite. "Kasos is related to Santorini, San Torini, and Barberton," Yen informed. "They are all likely meteorites. The population of pebbles appears to be from a different source from the cobbles."

A couple of sols later, Opportunity tested another technique for its stuck sister rover, reaching with its IDD or arm underneath its belly pan on Sol 1890 (May 18, 2009) to photograph its left middle and right middle wheels with its MI camera. Although the short-focus MI was never designed to snap this kind of photograph and while the images are blurry, they are good enough to show a fair amount of detail and prove the technique can work.

"That was cool. I was really tickled by how well that worked," mused Squyres, who suggested Opportunity try the gymnastic photography maneuver. "The last time I saw the middle wheel on that vehicle was in Florida. "We had done something like once before, when we had the big, big bad global dust storm a couple of years ago. It was when the wind was so severe and the dust so fine-grained that the dust managed to get in through the cover and coat the Mini-TES mirror even though the cover on the Opportunity's Mini-TES was closed," he remembered. "We didn't realize at the time what had happened. We were trying to take data with Mini-TES and it looked so crazy. We had never seen a coated mirror before. We didn't know what was going on. We thought maybe something had happened mechanically and it wouldn't open. So we thought about how Opportunity could verify if the cover was opening properly or not, and one way was to bring the arm up and use the MI to image the head of the PMA [Pancam mast assembly] to see if the aperture was opening and closing. We did that and it worked. It worked fine. You could see the cover really well."

Kasos

KasosOpportunity took this picture of Kasos on its Sol 1884 (May 12, 2009) as it approached the cobble for a close-up study. The rover used its panoramic camera (Pancam) to to this image, which was then rendered in false color by the Pancam team at Cornell.Credit: NAA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

But what made Squyres think of this latest maneuver was actually something that happened way back when the mission first landed in January 2004. "While the IDD was still stowed under the vehicle, we just took an image with the MI that was a health check, just to make sure the camera was working properly," he recalled. "It was. I remembered that the pictures it took were out of focus, but you could see hardware pretty well. I was surprised at how in focus the out-of-focus images were," he said.

Cut to five and a half years later. The team had Opportunity test the gymnastic photography maneuver first for obvious reasons. "With Opportunity, we have a controlled geometry. We know the configuration the vehicle is in and we know we can do it safely," Matijevic said.

"If we're going to try something for the first time and we have one vehicle that is having problems and one vehicle that is doing fine, then we're going to try it out on the vehicle that's healthy and doing fine and see if it works before we try it on the other vehicle that's having problems," elaborated Squyres.

By the middle of May, Opportunity's right-front wheel was showing improvement in the current levels after resting during the pebbles-cobble campaign. So, with its study complete, the rover moved on, driving about 20 meters (65.6 feet) on Sol 1891 (May 19, 2009). Once again, the team noticed a slight trend upward in the motor current for the right front wheel, but it wasn't enough to stop this rover. On Sol 1992 (May 20), Opportunity drove forward again, getting another 74 meters (243 feet) closer to Endeavour.

"It was driving forward and had been driving forward all through this past week," said Matijevic. "The currents are still elevated and so we're limiting most drives to 50 meters, which tends to be completed within about an hour." The engineers are also trying out a new strategy of driving shorter distances. "We're trying to do a couple of things here," he said. "We're trying to figure out if we can drive shorter distances and drive more days without elevating the current in the actuators as has been happening on the longer, 100-to-150-meter drives."

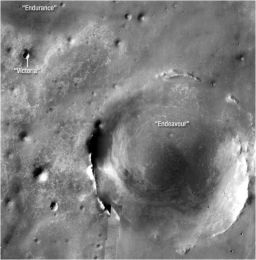

Opportunity's next big destination

Opportunity's next big destinationThe MER team has chosen a a crater more than 20 times wider than Victoria Crater as Opportunity's next destination. The rover began the long, 12-kilometer (about 7.5-mile) journey -- which p.i. Steve Squyres estimates will take about 2 years, with science stops along the way -- on Friday, Sep. 26, 2008 with a 152-meter drive. The crater, which is to the southeast of Opportunity's location at Victoria, dominates this orbital view from the Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) camera onboard Mars Odyssey orbiter. Victoria is the most prominent circle near the upper left corner of the image. This view is a mosaic of about 50 separate visible-light images taken by THEMIS. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / ASU

Elevated currents aside, for Opportunity, Sol 1897 (May 25, 2009) was a Memorial Day to remember. That’s when the rover pushed its odometer past the 10-mile mark, establishing yet another rover record and driving MER deeper into the history books.

The Mini-TES team and rover engineers who spent time in April working on "the best way" to safely expose the instrument's mirror to the Martian elements, agreed on a plan in May. It wasn't exactly something that was a no-brainer. "The software was designed to protect the instrument from direct radiation from the Sun by always ensuring that the mirror was safely stowed before and after Mini-TES imaging," Knudson explained.

Exposing the sensitive instrument to the harsh Martian element may seem completely wacky, but it's not really. "The optics of all the cameras have been affected over the mission, but there has been visible improvement on the cameras over time due to wind clearing events," Knudson pointed out. So, the instrument team and MER engineers tested a variety of methods to safely expose the mirror while minimizing the chance of seeing the Sun. Now, they’re ready. "We're going to open it up soon and see if Mars will clean it off for us," said Squyres. "Mars made it dirty and we'll see if Mars can make it clean."

In the meantime, Opportunity is roving into June. "We continue to see elevated currents to the right front wheel, so we're stopping every so often to rest it, and we'll be alternating from forward to backward driving, as well as limiting the length of our drives to some extent," said Matijevic.

"The goal for Opportunity," Squyres summed up, "is to cover ground and do it safely."

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth