Emily Lakdawalla • Apr 21, 2015

Rosetta update: Two close flybys of an increasingly active comet

In the two months since I last checked up on the Rosetta mission, the comet has heated up, displaying more and more jet activity. Perihelion is now only four months away, and the pictures are just getting more and more dramatic with time.

Rosetta has completed two close flybys -- one at a distance of only 6 kilometers, on February 14, and one at a distance of 14 kilometers on March 28. During both flybys, stray comet particles spoofed the star sensors that Rosetta uses to understand its orientation in space. Following the second flyby, pointing was affected enough that Rosetta's high-gain antenna rotated away from its Earth pointing, and the spacecraft eventually entered a protective safe mode. The spacecraft is fine and they are working to bring all the science instruments back online, but the entry into safe mode caused them to travel much farther from the comet than planned, and the navigational problems have forced the mission to replan their future trajectory and, consequently, science. It's all part of the fun challenge of doing something nobody's ever done before: orbit a comet as it approaches perihelion.

Rosetta's long residence at the comet paid off recently, as the OSIRIS science camera fortuitously caught a jet in the act of starting up. In an ESA blog post about the fortunate photos, principal investigator Holger Sierks is quoted as saying: "This was a chance discovery. No one has ever witnessed the wake-up of a dust jet before. It is impossible to plan such an image." In a sense, though, ESA was able to make this lucky observation happen by being at the comet for long enough to catch a lucky break.

I've just spent a pleasant morning reading through two months' worth of the Rosetta blog to catch up on how the mission has evolved. Until January, Rosetta was flying in circular, "bound" orbits, with the comet holding the spacecraft to its path. But as the comet has gotten more active and begun to produce more gas and dust, that gas and dust exerts drag on the spacecraft, preventing Rosetta from being able to maintain these bound orbits. Since February, though, it has flown further away, on "unbound" orbits, meaning that the comet's gravity no longer constrains the spacecraft's path. With these unbound orbits, Rosetta must perform regular trajectory correction maneuvers to maintain proximity to the comet.

When your spacecraft's orbit is unbound, a safe mode can mean a missed trajectory correction maneuver and an unplanned excursion. That's what happened during the March 28 flyby, summarized in detail in this blog post. An update from April 10 explains that Rosetta wound up in an escape trajectory and traveled as far as 400 kilometers away from the comet. There wasn't any real danger of Rosetta losing the comet, though, because the speeds involved are very slow and well within the capability of Rosetta's thrusters.

On April 1, a rocket firing began to return the spacecraft toward the comet, and it reached its target distance of 140 kilometers altitude on April 8. It is a terminator orbit, meaning that the spacecraft travels around the comet in an orbital plane that coincides with the night-day boundary, and it sees the comet at roughly half phase at all times. As of that update, the plan was to go into pyramid orbits with minimum altitudes of 100 kilometers throughout the rest of April.

The change in Rosetta's trajectory unfortunately meant a complete replanning of targeted science observations and a reconsideration of the entire orbit strategy, which involved a few more of these close flybys. As of April 10, not all the instruments had been returned to normal operation yet.

Meanwhile, the unplanned excursion from the comet has not affected Rosetta's plans to listen for the Philae lander. Philae mission manager Stefan Ulamec still does not expect conditions to favor Philae's waking until at least next month, but listening campaigns were conducted over a period of about a week beginning March 12 and April 12, just in case.

Throughout all of this work, the NavCam is continuing to photograph the comet to good effect. ESA has begun to release NavCam data using its archive image browser, which presently only contains Rosetta data. It includes NavCam data from the cruise phase of the mission (which was already public; I worked through that archive and blogged about some of the images a while ago), and also includes early images from the comet phase of the mission. As of this writing, it contains images taken through August 1, when Rosetta had approached to within 850 kilometers of the comet. They plan to release images on a monthly basis, eventually catching up to the point that they release pictures approximately six months after the images were originally taken.

I can't possibly include in this post all the great photos they've released in the last two months. I'll pick a few favorites, but also provide links to help you browse. First, some oldies but goodies: photos from October "bound orbits" at 10 kilometers: Three super close up images and another one. The image below contains both "dunes" and a funky sort of foldy lineament. All of the closeup images contain bizarre morphology.

Here are many photos from the close flyby at 6 km on February 14: 35.0 km at 04:32 UT; 12.6 km from center (10.6 km from surface) at 10:15 UT; Saw its shadow at 12:39 from distance of 6 km from surface; 8.9 km from surface at 14:15 UT; 15.3 km at 16:12 UT; 31.6 km at 19:42 UT. My favorite has to be this OSIRIS image, which actually contains Rosetta's shadow, visible as a blurry rectangle because the spacecraft was still at a high enough altitude that it did not fully block out the Sun as seen from the comet's surface.

I also like this artful crop of a NavCam image that contains such a wide variety of surface types.

Following the February 14 flyby, Rosetta traveled up to 255 kilometers from the comet on February 17, the farthest it had been since August 2014. February 15: 125 km. February 16: 226.5 km. February 18: 198 km. February 20: 118.5 km. Here's one of the distant views:

Rosetta then perfomed a series of maneuvers in unbound orbits to position it for the next flyby. February 25: 81.9 km. February 26: 94.3 km (4 images). February 26: 87.1 km. February 27: 98.2 km. February 27: 101.7 km. February 28: 102.6 km. March 6: 82.9 km. March 6: 85.5 km. March 9: 71.9 km. March 14: 85.7 km. March 14: 81.4 km. March 18: 81.4 km. March 20: 81.7 km. March 21: 82.6 km. March 22: 77.8 km. March 25: 86.6 km. Quite a few of these are overexposed, which is intentional; the goal was to provide context imaging of the jets and coma for the Alice instrument. Several of these photos are included in the montage I used to open this post:

On March 28, Rosetta accomplished another flyby, passing 14 kilometers from the surface (16 kilometers from the center at 13:04 UT. Released images include ones taken from 20.2 km on approach at 09:33 and 09:51; from 16.6 km, just after flyby, between 14:35 and 14:53; and from 31.3 km, 7 hours after the flyby. Here's a striking closeup of the boulders that lie in the comet's neck. I'm intrigued by the subtle scalloped scarps adjacent to the boulders -- is the ground collapsing there with increasing comet activity?

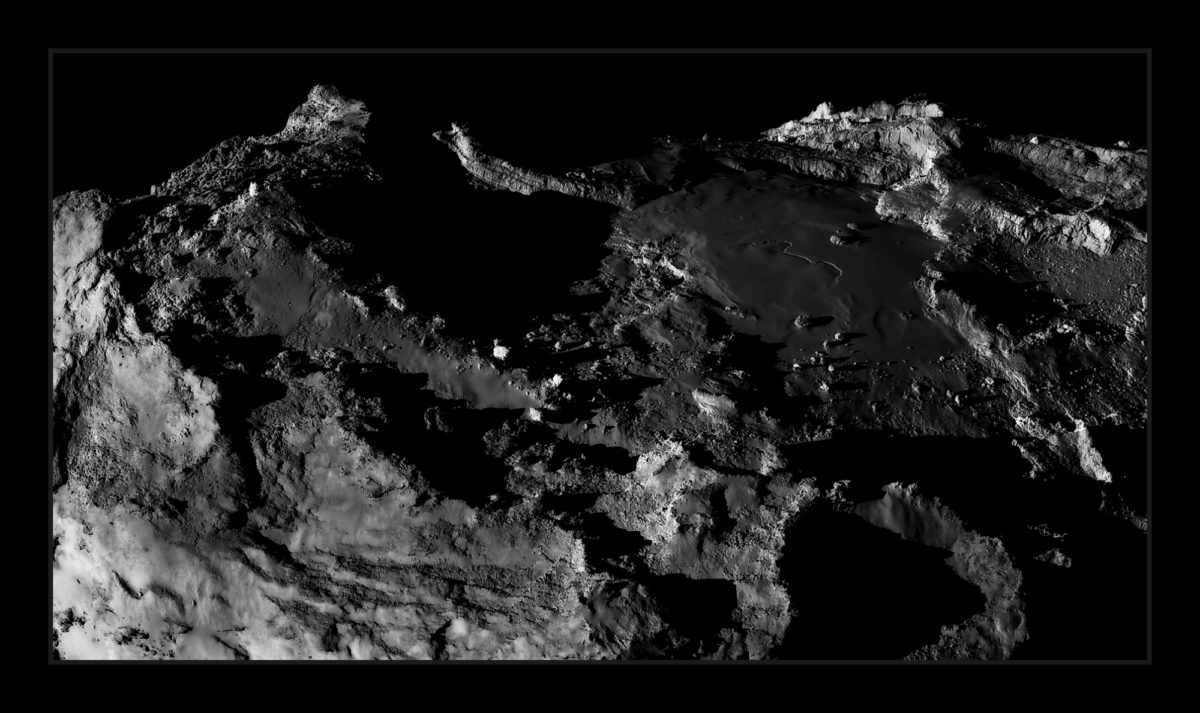

And then there's this striking, moody landscape.

The safe mode resulted in Rosetta traveling quite far from the comet, up to 400 kilometers; photos taken since then have been at greater distances than most of the imaging performed since August. April 2: 385 km. April 8: 137 km (4 frames). April 12: 146.8 km. April 15: 170 km. April 15: 165 km. From such a distance, we can appreciate the comet's jets in their full glory. And it's only going to get more active!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth