Emily Lakdawalla • Apr 19, 2013

A walk among the mesas of Deuteronilus Mensae

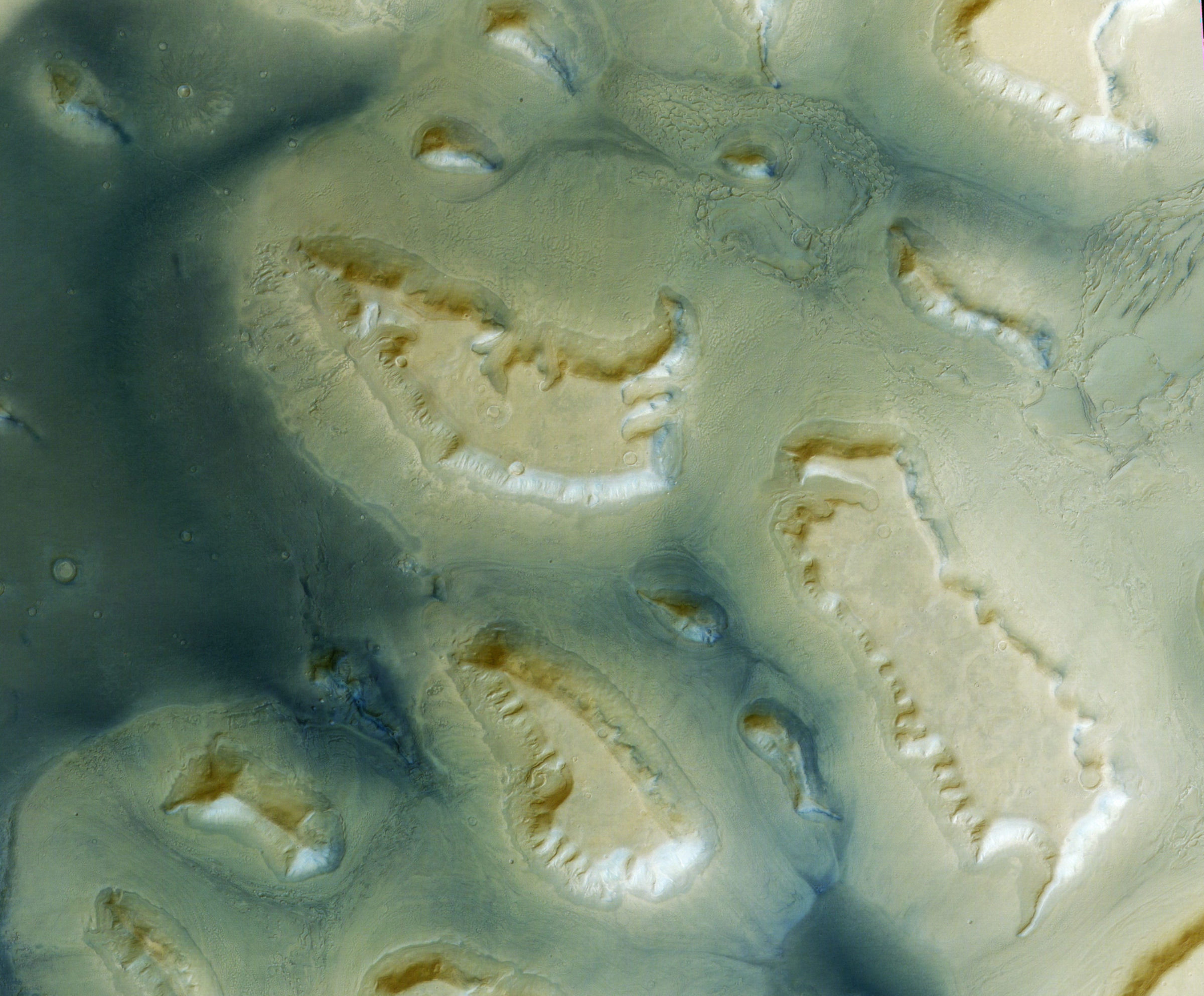

Here is a pretty picture from a kind of terrain unique (as far as I know) to Mars: the so-called "fretted terrain" of Deuteronilus Mensae. The photo is from Mars Express' High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC).

"Fretted terrain" is a descriptor that first appeared after the Mariner 9 mission. Robert Sharp described it in a 1973 paper: "Fretted terrain is characterized by smooth, flat, lowland areas separated from a cratered upland by abrupt escarpments of a complex planimetric configuration....it is the product of some unusual erosive or abstractive process that has created steep escarpments and caused them to recede into a complex planimetric configuration leaving behind a smooth, flat lowland surface." Here is the Mariner 9 image that he was describing. You can see the mesas from the Mars Express photo on the right side, just above the center.

In this description, Sharp was (properly) carefully describing but doing very little interpretation of the shape of the landscape. Fretted terrain has flat lowlands and flat-topped uplands. If you assume that the flat uplands were originally all part of a continuous flat layer, then you must conclude that something happened to carve away whatever this layer was, eroding down to a presumably more resistant lower layer. But what was that erosive process? Why is the upper layer so much easier to erode than the lower one? Why has it eroded in some places and not in others? We still don't have good answers to these questions.

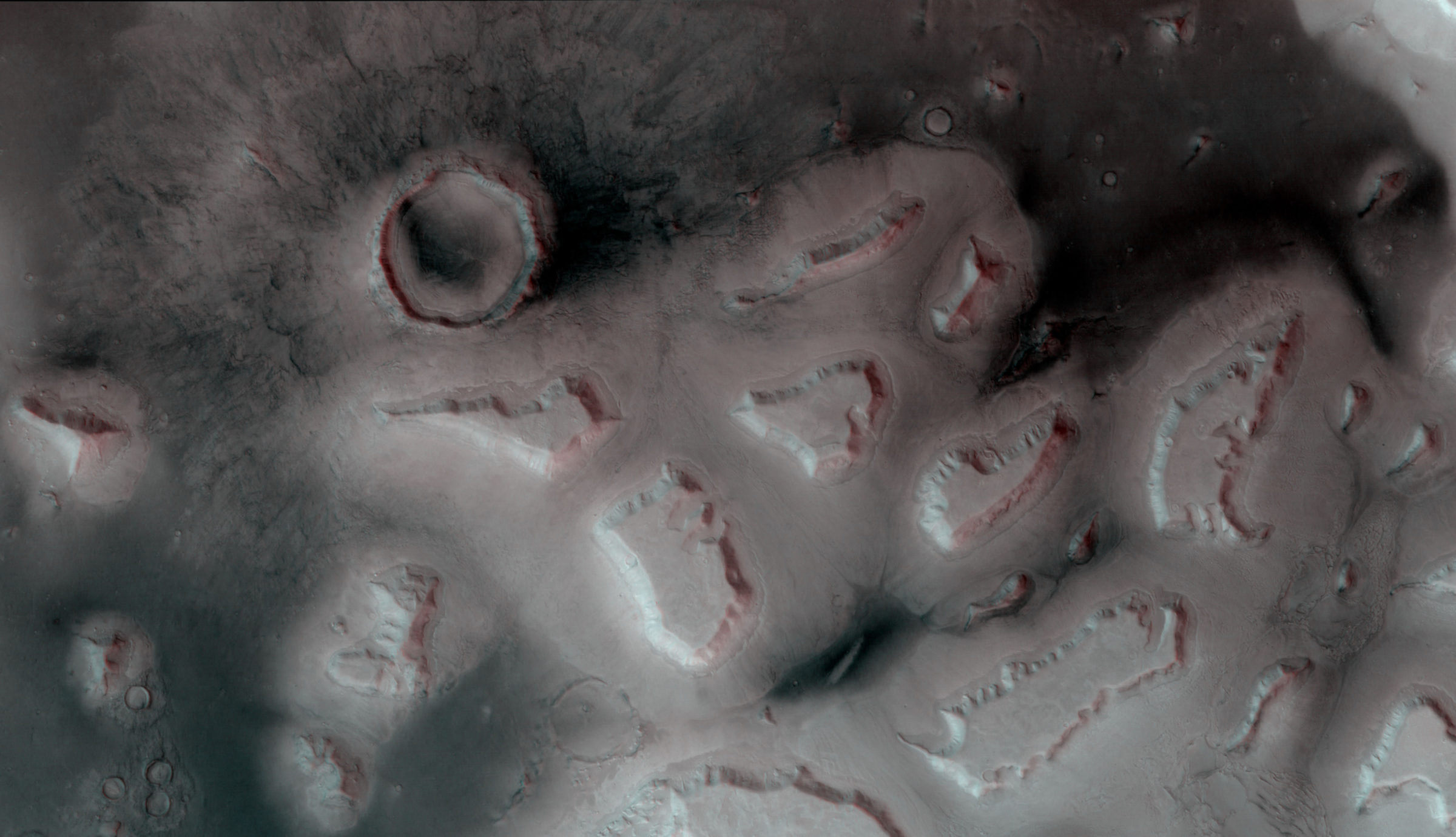

Because my original photo is a High-Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) image, there is, of course, stereo data available for a 3D view. Here's a red-blue anaglyph of some of the region's mesas. Becuase of the way that HRSC works, you have to either turn your head sideways or turn the picture sideways in order to see its images in 3D, so this image has been rotated to put north to the right. If you don't have 3D glasses, scroll just below the images and try out the other stereo-viewing options; click on the red-blue one to bring up a page where you can download left- and right-eye images for use in other stereo display methods. This stereo-image display capability is a new one on our website that I am really excited about. Tell me what you think!

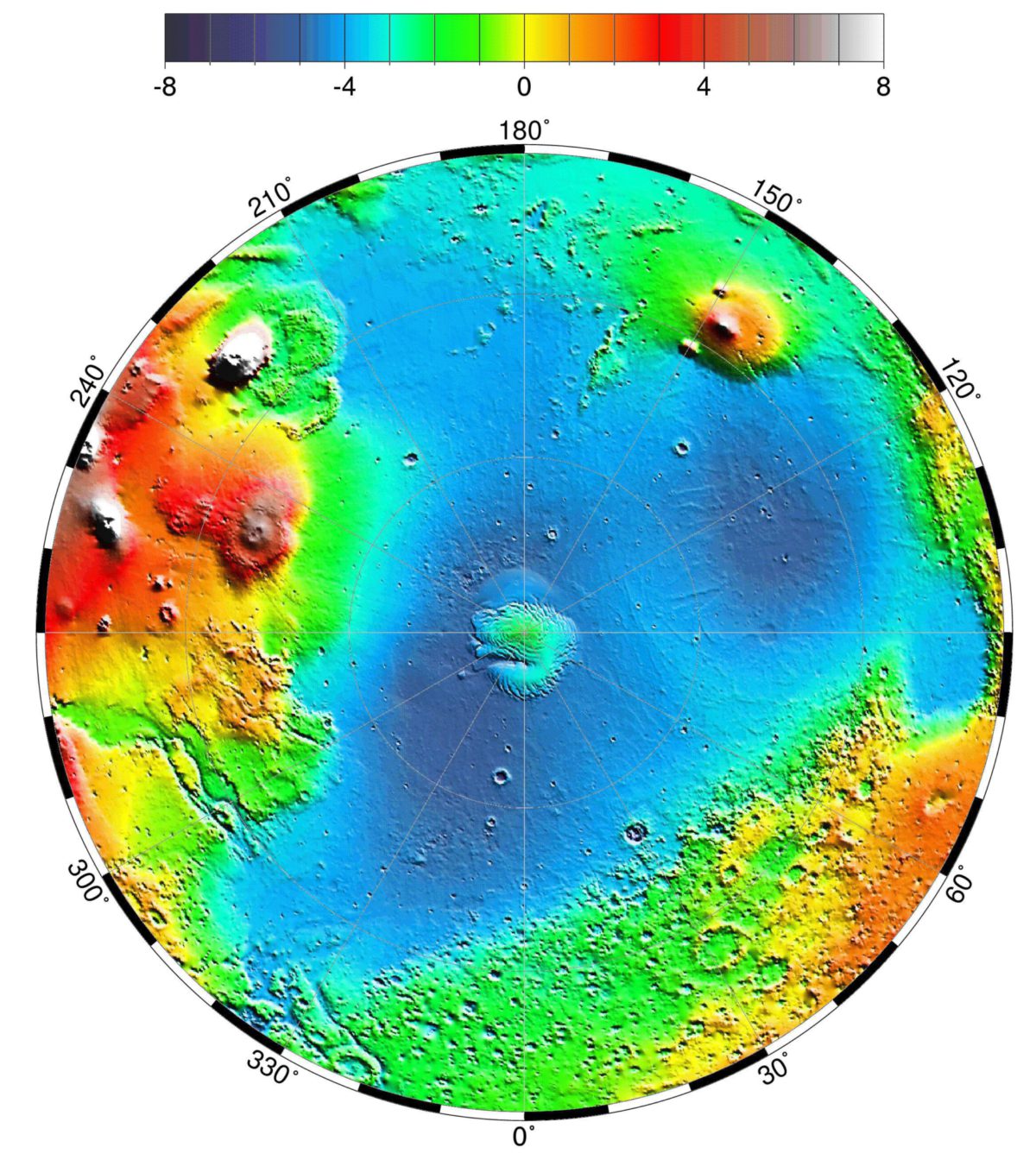

This upland-and-lowland terrain dichotomy is quite ancient. But there may be something more recent, and wackier, affecting Deuteronilus. Although there are other regions of mensae -- with names like Aeolis Mensae (near Curiosity) and Protonilus Mensae -- Deuteronilus is different because it is uniquely far north. When we talk about the "northern lowlands" and "southern highlands" it's easy to lose track of the fact that "southern highlands" terrain occurs in the northern hemisphere, too. Here's a pole-to-equator topographic map of Mars' northern hemisphere. There are high-elevation provinces at 240 and 150 degrees longitude associated with volcanoes. But the high-elevation region located from around 330 to 60 degrees east isn't volcanic; that's highlands terrain poking well north of the equator. The Deuteronilus Mensae form the northern edge of this, and they're at pretty high latitude, about 40 or 45 degrees.

Why does that matter? It matters when you try to explain the odd erosive behavior of Deuteronilus' mesas. Check out this crop from the original photo:

The plateau almost seems to be melting, and there's a bizarre texture in the light-colored apron of debris located at the base of the plateau. There are several lines of evidence that suggest that there may be ice here, buried beneath the surface. Here's a feature on the Mars Odyssey THEMIS website that provides thermal evidence. And here's a paper from researcher David Marchant's website (PDF) about these lobate debris aprons and how they might have to do with a recent Martian ice age. Cool, huh?

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth