Emily Lakdawalla • Apr 14, 2014

Pretty picture: Sunset over Gale crater

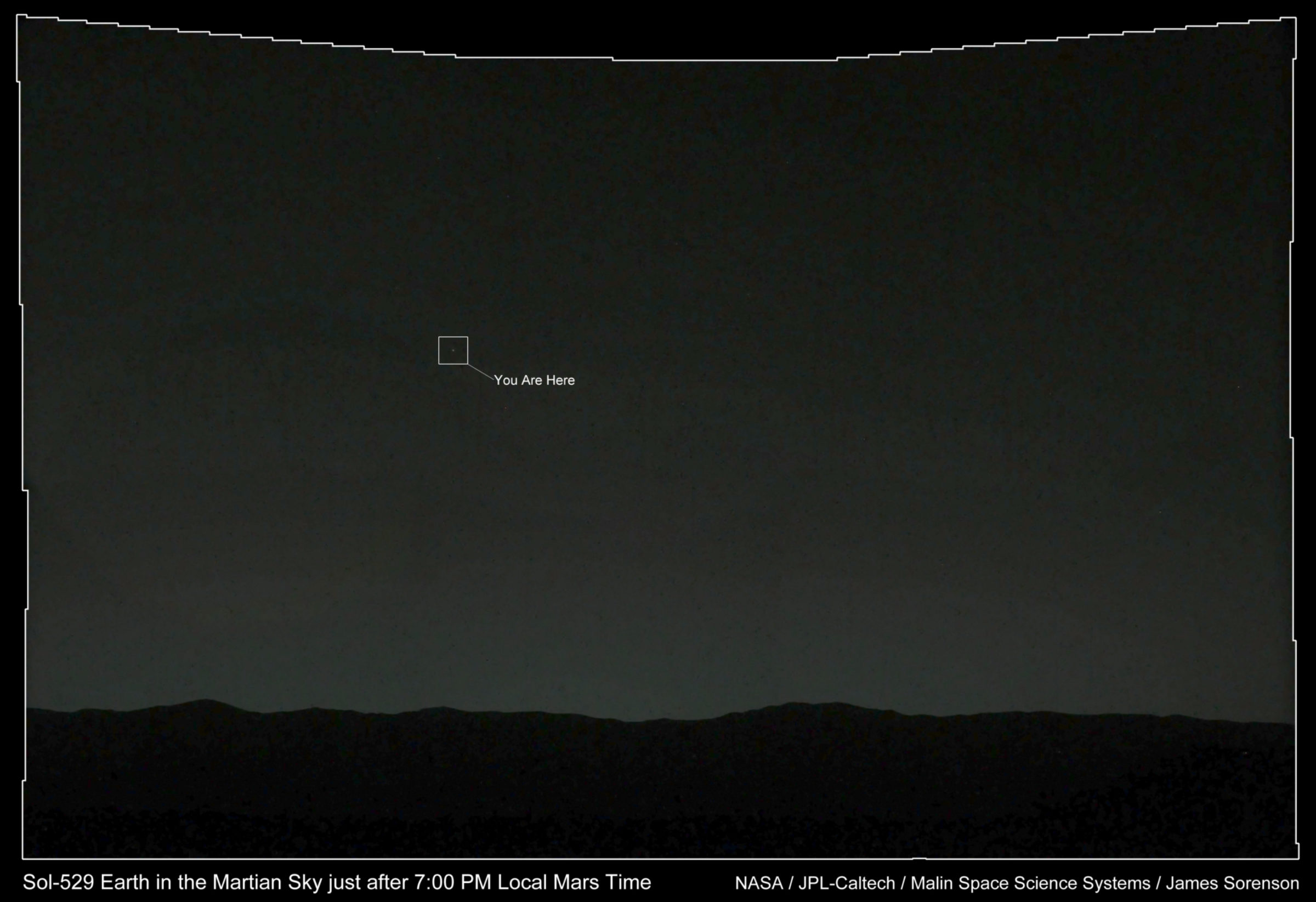

Imagine yourself on a windswept landscape of rocks and red dust with mountains all around you. The temperature -- never warm on this planet -- suddenly plunges, as the small Sun sets behind the western range of mountains. Only a blue glow is left behind to mark its departure -- a strange color for a sunset, telling you you're on a strange world.

It's beautifully composed, timed perfectly for just after sunset. It takes a lot of careful planning to make a photo like this one work. And it's just the latest in a series of lovely after-sunset photographs that Curiosity has performed. You may recall one they took a couple of months ago, showing Earth and Moon setting over a similar horizon. It was taken later in the evening, so the crater rim is just barely visible against the hardly-lighter sky.

Whenever any rover takes a photo of the sky, I know atmospheric scientist Mark Lemmon is involved. Back when they took the Earthset photo, I sent him an email to ask him him to tell me about what goes in to capturing these awe-inspiring shots.

Mark told me that they gained a lot of experience with nighttime imaging when comet ISON was passing by Mars. Their attempts to image ISON turned out to be ineffective, because the comet was too faint, but Mark said "The preparations for ISON allowed us to get a feel for exposure times for near-point sources of a known magnitude. We also did a focus test for point sources at the cold nighttime temperatures."

Mark said that the Earthset photo was a little darker than he had wanted it to be. "I wanted a brighter twilight, but predicting twilight 60-plus minutes after sunset is tricky. It depends a lot on upper atmosphere dust hundreds of kilometers away. We have a bunch of Spirit experience, but the low tau really moved the model predictions. So, I went with a time when the worst case twilight was not too bright." "Tau" is a quantity that describes the opacity of the atmosphere. Low tau means there's not much dust in the atmosphere. The sky is not very dusty right now, and that will tend to make the twilight sky darker; but they had to be mindful of the possibility that a small increase in dust could make the sky a lot brighter, which would make Earth harder to see.

With the experience of the Earthset photo under their belt, the mission was ready to try shooting a photo closer to sunset, and the result was the image at the top of this post. Mark said: "I was happy with that--in terms of the sky appearance, it came out just how I had pictured it when planning. Planning was more complex than usual. We had to manage sun safety for ChemCam. We all knew, of course, that the Sun could do no harm at the time. But flight software doesn't know about the rim." They have to be careful not to point the ChemCam telescope in a direction where the Sun could shine directly into it, and ChemCam is boresighted nearly the same as the Mastcams, so this is, indeed, difficult to plan, requiring a lot of safety checks, and precise timing that accounts for the topography of the crater rim. "We passed up a chance to get it a few sols earlier, because I was very picky about the time."

Every time I post one of these images, I get one or two killjoy commenters who complain about the time and resources spent on an expensive mission for tourist snaps. These photos do have scientific value for the study of atmospheric properties -- that's Mark's research specialty, in fact -- but I'd be lying if I said that these tricky-to-plan images were taken just for science reasons. A prime purpose of these photos is their value for public outreach, something Mark is committed to, in addition to being committed to good science. He told me about the science and art of the Earthset sequence: "We took the picture because it was a cool picture to take, and I think we have an obligation to do things like that. But I squeezed in some science by imaging the stars Elnath and Regulus. That gives me a nighttime optical depth to look for ice clouds and such. Those images were also useful in correcting the camera's dark current pretty precisely in the Earth images. It really needed some twilight, so that we were not just a point of light, but we were part of an alien sky."

Personally, I'm glad the scientists and engineers on these missions are conscious of the aesthetic value of the images that they take of other worlds. I've watched them plan targeting of image mosaics, carefully framing exactly the parts of the view they need for their science objectives, but also stepping back and considering whether the image encompasses enough horizon to make it visually pleasing, as well.

Photos like today's sunset image make me feel as if I'm there, on Mars, with all the rest of the people of Earth, embodied in one robot, staring at our common sun, sinking below an alien horizon. That's cool.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth