Emily Lakdawalla • Apr 12, 2016

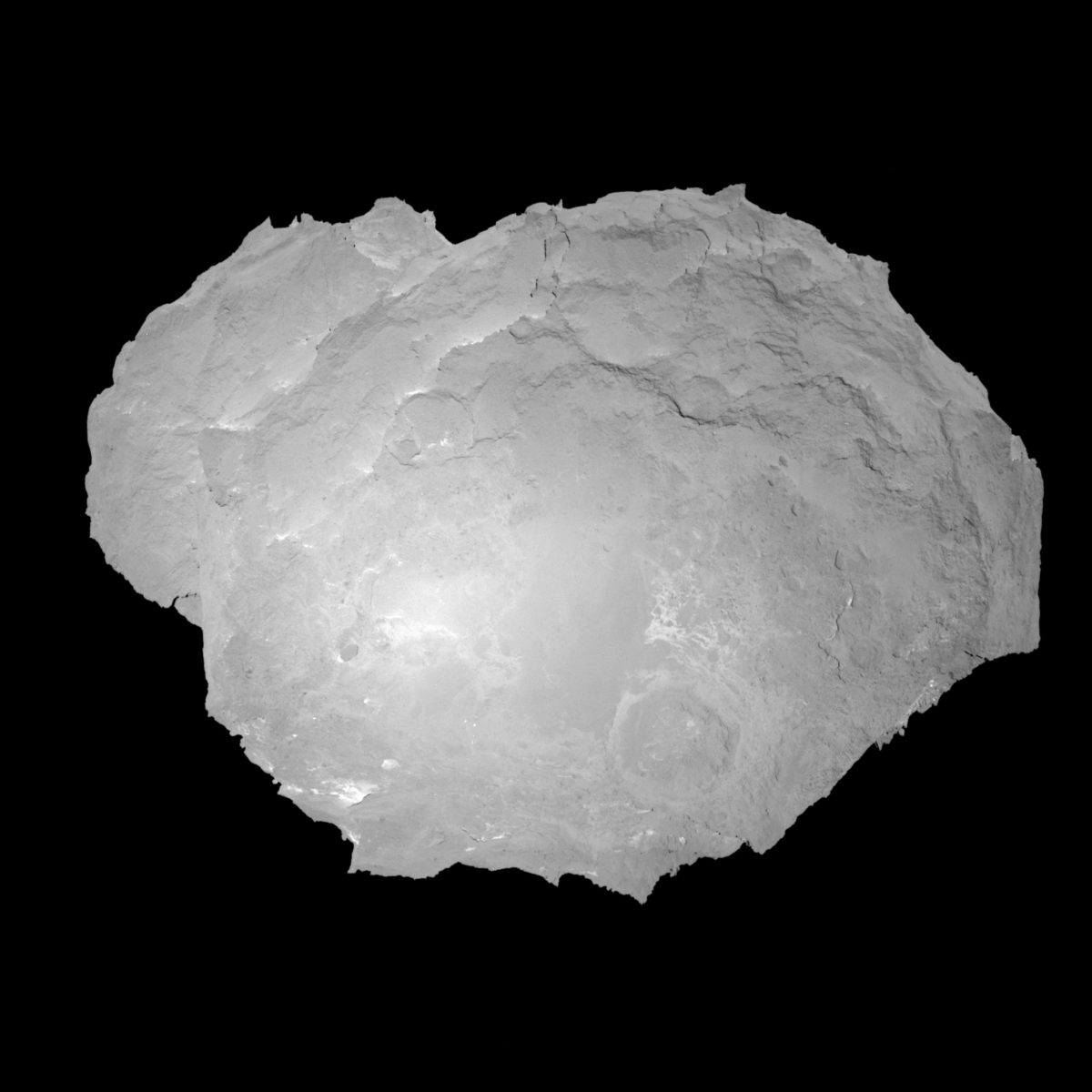

Opposition surge comet

Today, the Rosetta OSIRIS team's Image of the Day is this highly unusual view of the comet with the Sun very nearly behind the spacecraft. As with all OSIRIS images, it is worth it to click through twice to enlarge it to its full size. However, one of the most scientifically interesting aspects of this photo is best viewed from a distance: the opposition surge.

Opposition surge is an optical effect of rough surfaces. On just about every scale, this comet has a rough surface. The little lumps and bumps of topography on a rough surface cast little shadows on other visible parts of the surface. When you view a rough surface from a distance, you can't see any of those little individual shadows, but together they have an effect of darkening the surface. But that changes when the light source is directly behind you. You can't see any shadows, because they are being cast underneath all the surfaces that you can see. The surface at the subsolar point appears brighter because you can't see the shadows anymore. By measuring how large the opposition surge is, and the area over which it is visible, scientists can deduce some of the physical properties of the surface at scales much smaller than can actually be seen in photos.

Opposition surge is visible when you are observing an object at a phase angle (the angle from light source, to object, to observer) of close to zero degrees. Here's a little visual explainer of phase angle for another object that shows an opposition surge, Saturn's moon Rhea. I made this diagram for a longer post explaining phase angle.

The Rosetta photo reminded me of one of my favorite space exploration images, a similar zero-phase view from Hayabusa of asteroid Itokawa.

We can see Hayabusa's shadow in this photo because Hayabusa was much closer to the comet, so close that an observer on the comet's surface would have seen Hayabusa blot out the Sun entirely. Rosetta hasn't gotten a photo from that close...yet. Toward the end of its mission, this September, it will be spiraling ever-closer to the comet, and recent testing work on a bench model of the OSIRIS Wide-Angle Camera shows it's capable of shooting photos from distances as close as 15 meters. But Rosetta would have to be close and in exactly the right image geometry to shoot its cast shadow on the surface. I'm not sure that that will happen, but since there are good scientific reasons for doing low-phase observations from a variety of distances, I'm hoping!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth