A.J.S. Rayl • May 03, 2017

The Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Closes in on Perseverance Valley

Sols 4689 - 4716

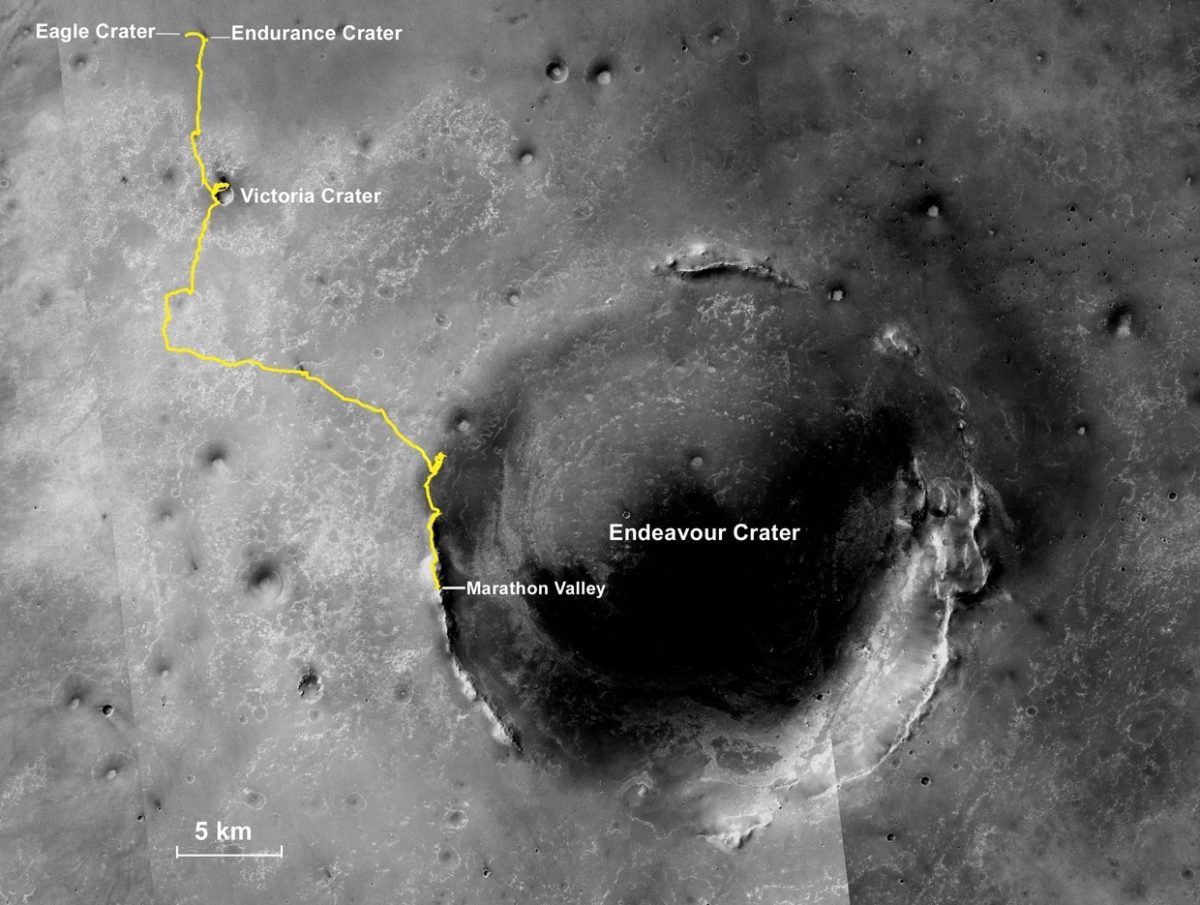

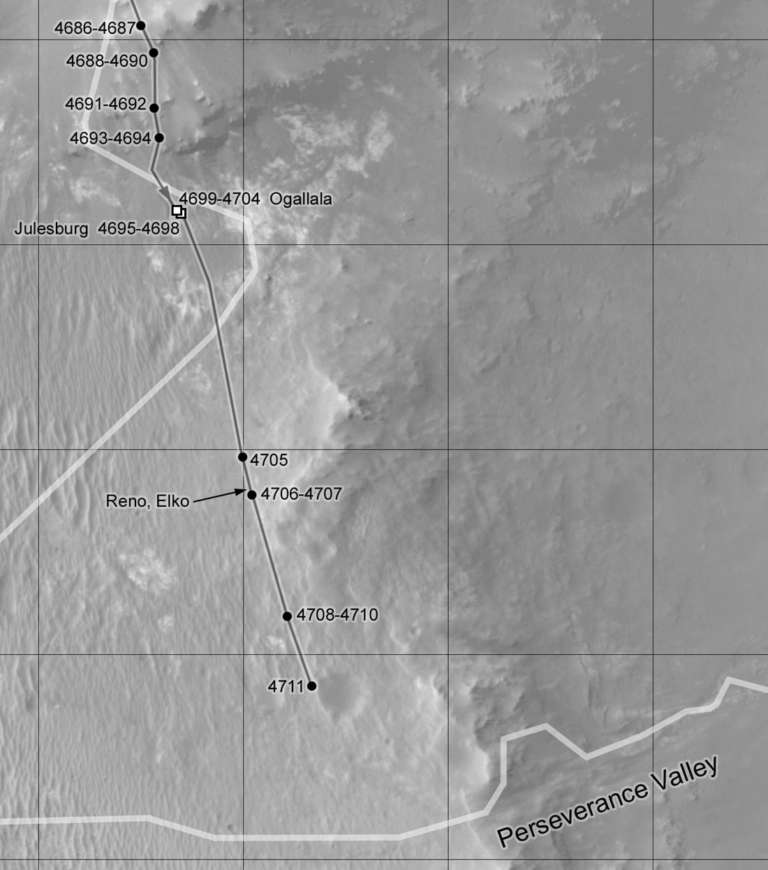

Opportunity spent the month of April 2017 outside the western rim of Endeavour Crater, cruising toward Cape Byron and Perseverance Valley, the centerpiece of the Mars Explorations Rovers (MER) tenth extended mission.

The veteran robot field geologist worked hard to pick up the pace during the last month, logging 10 drives and covering about a quarter of a mile. “We are now within striking distance of Perseverance Valley,” said MER Project Manager John Callas, of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), at April’s end.

Opportunity earned her stripes as ‘Little Miss Perfect’ long ago and the rover is keeping true to that distinction. NASA’s senior Mars ‘bot is arriving at the next major science attraction sooner rather than later, in roving good shape, and life is good at Endeavour Crater.

“There is a building excitement,” said MER Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis. “It won’t be long now before we will be looking into Perseverance Valley.”

After being confined to roving around in relatively small areas compared to the open expanse of the Meridiani Plains that she spent so many years crossing, Opportunity and her drivers finally had the chance in April to put pedal to the metal and just drive. “We’ve been making astonishing progress,” said MER Rover Planner Ashley Stroupe, of JPL, the birthplace of all NASA’s Mars rovers. “We’ve been on much smoother terrain and it’s been much easier to drive.”

In fact, on one drive Opportunity sprinted for more than 130 meters (about 430 feet) in a dash the likes of which she hadn’t done probably since leaving Cape York about four years ago. It made drivers on Curiosity duty, well, a little envious.

“It was a heck of a drive,” said MER Lead Flight Director Mike Seibert, of JPL, who split driving shifts that day with MER Rover Planner Paolo Bellutta, the rover robotics expert who has charted Opportunity’s routes since Victoria Crater. “The driving has been going incredibly well,” he concluded.

Averaging two to three drives each week, Opportunity, by all accounts, made impressive progress to Perseverance Valley while also taking care of the other routine business of roving Mars, and packing in a few science investigations along the way. One outcrop puzzled the science team, being, as it turned out, bedrock with a somewhat familiar composition, but one that did not neatly match any strata the mission has found so far. “Mars still surprises us,” said Arvidson.

They will continue analyzing that data. But it never ends. There’s always something. The MER science team recently spotted some linear features in the terrain near the head of Perseverance Valley. “They may be fractures or shorelines that extend outward toward the plains, to the west,” said Arvidson.

Fractures? Shorelines? Each of those possibilities points to past water, but all eyes in April remained focused first on Opportunity getting to Perseverance Valley.

It’s no wonder. From questioning if it was even possible … to mapping it and proposing it … to anticipating this arrival … and now closing in, it’s been a long haul. “We saw this thing a long time ago and for the longest time I didn't even dare talk about it, because it seemed so impossibly far off,” recalled MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres, of Cornell University, back in January.

Now it’s ‘Hello Perseverance.’ Although this ancient gully is truly old, it represents the study of something new for the MER mission, and Opportunity is delivering on another dream site. “Even after 13 years, we are excited about having this chance and are definitely looking forward to getting on with it,” said MER Project Scientist Matt Golombek. “This is a new chapter in our exploration history, and nobody else is writing it.”

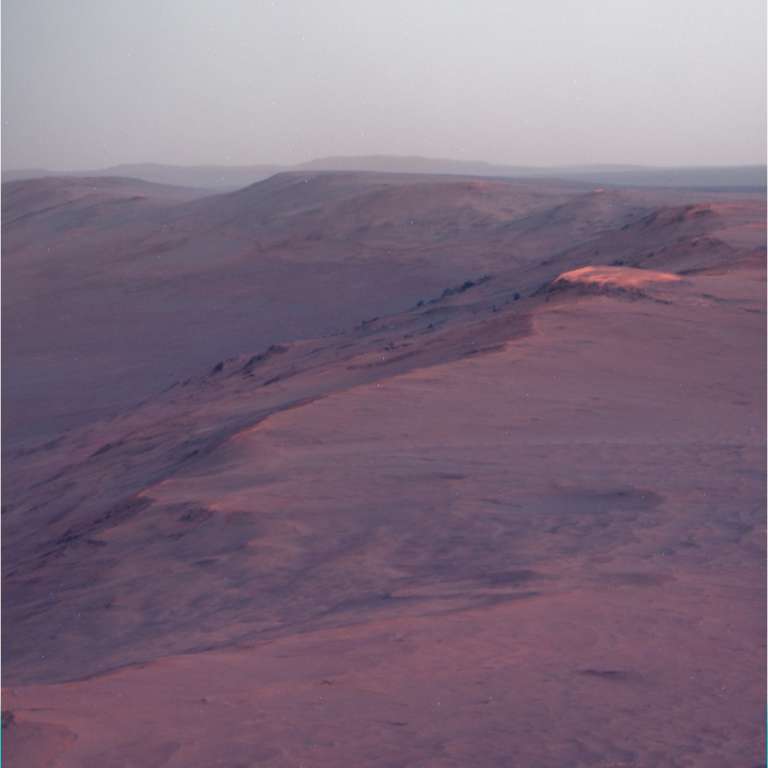

MER is the first Mars surface mission to explore Noachian Period Mars or, in other words, ancient Mars. Ever since pulling up to the western rim of Endeavour in August 2011, Opportunity has been time-traveling through the Red Planet’s geologic past, as she has climbed up and roved around layers of bedrock.

The robot geologist has traversed from the Hesperian Period some 3-3.6 billion years ago, a transitional time of widespread volcanic activity and catastrophic flooding that carved immense outflow channels across the surface, back to the Noachian Period, the epoch 3.7 to 4.2 billion years ago when the Red Planet was believed to be more like Earth, warmer and wetter, with perhaps an ocean, as well as rivers and lakes on the surface.

Endeavour Crater itself dates to the Noachian Period and Opportunity found the mission’s first surface evidence of ancient Mars at Cape York on Matijevic Hill in 2012-’13. Discoveries there included the oldest strata found to date, the Martian ground when the impact that created Endeavour hit the surface (Matijevic Formation); remnants of ancient clay minerals (Esperance); and another ‘new’ old rock layer (Grasberg) that the MER scientists think formed after the impact.

Within Perseverance Valley, the MER scientists hope Opportunity will be able to rove deeper into the Noachian Period and find more evidence of what Mars was like in this spot billions and billions of years ago – and if water once ran through these parts.

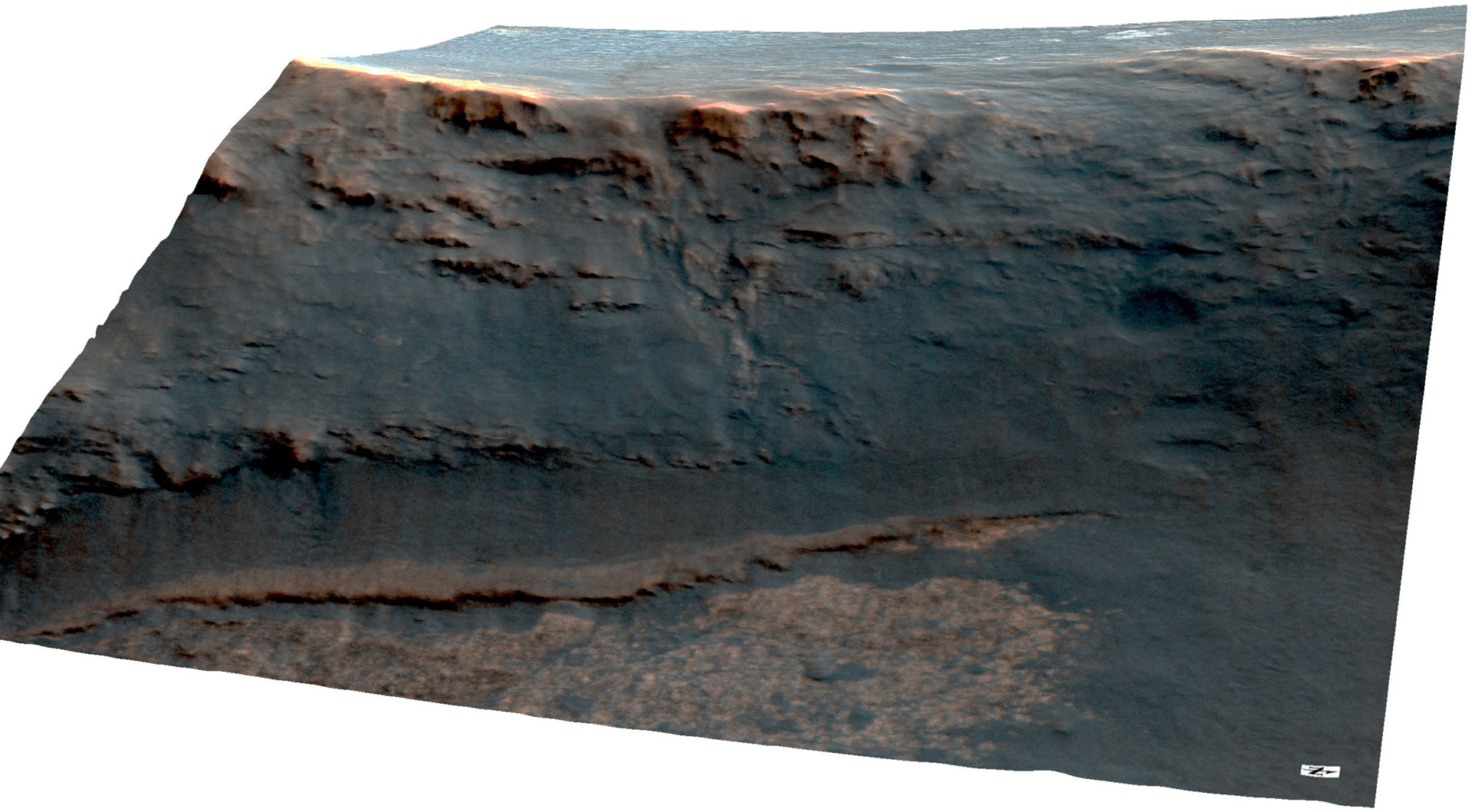

From the overhead images taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), the MER scientists were thinking that this ancient gully may have a great story to tell about past water. Uncovering this kind of evidence is exactly what NASA created and dispatched Opportunity and her twin, Spirit, to do, in an exploration campaign the agency called ‘Follow the Water.’

Compared with other locations where Spirit and Opportunity uncovered evidence of past water, Perseverance Valley could open the floodgates, metaphorically speaking, on the story of an ancient environment at Endeavour when the planet was still forming. Certainly the rover is in the right time zone to find something new of historic importance.

In coming months, the MER scientists plan to define and describe the morphology of this site and test at least three hypotheses to determine whether wind, flowing water, or a debris flow liquefied with water, carved this ancient feature all those billions of years ago. “We want to be careful here,” cautioned Callas. “This thing is ancient. We don’t want people to think we expect Opportunity to find water in Perseverance Valley. And we’re not looking for microbes either. What we’re trying to understand is what happened here, at this particular location, a long, long, long time ago on Mars.”

Aiming to please, Opportunity pressed on throughout April, making her final drive of the month on the last sol of the month. She pulled to a stop some 40 meters (about 131 feet) from the head of the valley. “We are almost there and the rover is doing very well,” said Chief of Rover Engineering Bill Nelson, of JPL. “We have had a remarkably benign month and Opportunity continues to do everything we ask her to do.”

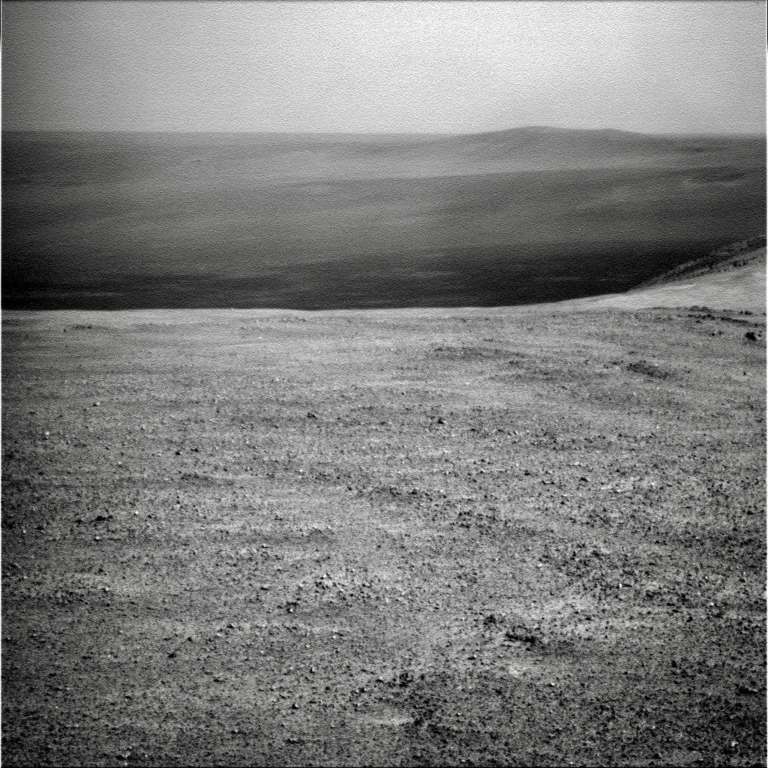

As April faded, the images the rover sent home from that last drive of the month showed glimpses of Perseverance Valley, right there, stark in the raw images. “It’s nice and flat, and all of the sudden, it just disappears over the edge,” said Callas, describing the view.

It will be a while before Opportunity ‘disappears’ over that edge however. “We will arrive at the entrance of the valley quickly now, but we’ll want to do some reconnaissance work,” said Seibert. “Before we commit to taking the rover down that slope, we want to make sure we know what we’re getting ourselves into.”

No matter how intriguing this new site is, no matter far the rover has driven or how long it’s taken the mission to get here, the team has no plan to send Opportunity into Perseverance ‘guns-a-blazing.’ “We’re not cowboys,” scoffed Golombek, playfully.

Truth told, the ops team is not quite sure how Opportunity should approach this new site or from where exactly the rover should head down into the valley. “There’s this ripple at the end, and it looks like there may be a way on the north side but there are bunch of rocks there,” Golombek said, pointing out some of the obstacles.

In all likelihood, the team will want the rover to spend several weeks around the head of the valley checking the place out. “We want to do a wide baseline stereo survey of this ancient feature,” said Callas.

That plan calls for Opportunity to pull up to the rim, look down from widely separated points and shoot stereo panels of the whole valley, from the left side of the exposed wall all the way down the valley and then all the way up the other side of the valley. With that data, the ops engineers can generate a good digital elevation model of the entire area. “And with that, we can effectively plan and carry out what we want to do,” Callas said.

In addition, there is a “slew of imaging that is part of our investigation of the valley,” said Golombek. Opportunity will probably be focusing her cameras on the newfound linear features that could be so telling, the rocks on both sides of the valley, and any other geological formations that might reveal clues as to what happened here long, long ago.

Perseverance holds secrets. Of that there is little doubt. How many and how significant remain to be seen. The chatter at the end-of-sol meetings, and at the water coolers in between meetings about what Perseverance is and what they may find has been lively and interesting. Soon, Opportunity will be cutting to the chase.

“What you call this feature really doesn’t matter,” said Golombek. “What matters is – can we distinguish if this feature formed by water? If so, was it a mud-debris flow? Or was it formed by ‘clear’ water? Or was it a dry avalanche?”

Most of the MER scientists are feeling fluvial, and seem to be leaning toward one of the carved-by-water theories. That leaves the dry avalanche theory as the odd theory out or the least popular of the three hypotheses under consideration, but the science team will be looking to prove or disprove each one.

“We have a set of hypotheses as to what this thing might be and we’re going to test those hypotheses,” said Callas. “That is what science is all about.”

The resilient little golf-cart-sized rover and her crew on Earth have their work cut out for them in coming weeks. But with a tenth wind behind them, they are revving up to write this next chapter in Mars exploration history – and they’re ready to roll wherever the science leads them.

Coming up: The fall equinox in the southern hemisphere of the Red Planet occurs on May 5, 2017. That day also marks the start of the MER mission’s eighth Mars year. The next Martian winter begins November 19, 2017.

When April dawned at Endeavour Crater, the dusty haze in the skies from the regional storms of February and March was slowly thinning, with the Tau recorded at around 0.981. Opportunity was producing a respectable amount of power, upwards of 400 watt-hours, but her dust factor had decreased to 0.597, as fallout from the storms rained down.

The rover began the month on Sol 4688 (April 1, 2017) with a 13.36-meter (43.83-foot), drive, continuing her journey from Rocheport to Perseverance Valley. As usual, she took the routine post drive images with her Navigation Camera (Navcam) and Panoramic Camera (Pancam).

That same sol, Opportunity linked with MAVEN for a UHF relay pass. Both rover and orbiter performed well, but an overlooked, precautionary filter caused an issue with the data returned. “Unexpectedly we received 35.1 megabits of data, of which 22 megabits were fill data,” said Nelson, “a fixed glob of stuff that just repeats over and over again.”

In preparation for a communication pass, the rover normally packetizes data according to 100 different priority levels, with the highest priority getting packetized first. However, if the ops engineers feeling insecure about a given UHF passes, they can turn on a filter to protect critical data. “It’s called nocritD – for no critical data,” said Nelson. “This filter says, basically: ‘Do not send any critical data.’”

With the upcoming MAVEN pass, Opportunity packetized the data, reorganizing it by priority as usual. “It packetized a lot of critical data and not very much non-critical data, because it figured we would send mostly the critical data, unaware of the filter,” said Nelson.

When the MAVEN pass took place however, the filter was in play and so the rover only sent data packetized as non-critical data. “And there wasn’t much of it,” said Nelson. The filter faux pas was quickly discovered and the MER ops engineers have since then, come up with several workarounds so it doesn’t happen again. Even on Mars with an old ‘bot, one can learn something new to remember.

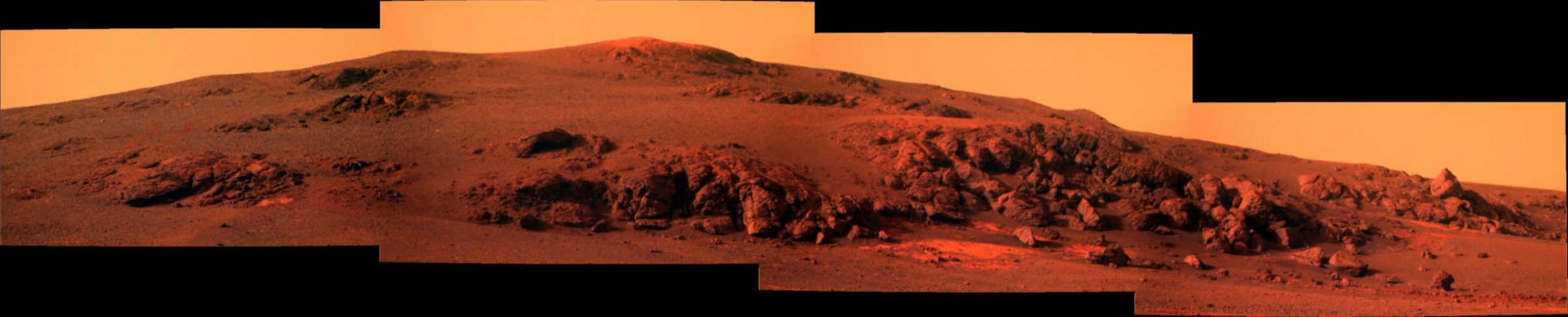

Opportunity hit the road again on Sol 4691 (April 4, 2017) and put 27.82 meters (91.27 feet) behind her. The rover then spent some time taking targeted imagery of something else that had caught everyone’s eyes, a bright mesa-like formation about 200 meters south of Perseverance Valley. The team nicknamed it Winnemucca, after the Nevada city stop on the Transcontinental Railroad, the mission’s new target naming theme.

“Winnemucca is really unusual, a kind of circular plateau sitting on the crest of Cape Byron with a bunch of black rocks surrounding it,” said Arvidson.

It was intriguing enough for the scientists to consider dispatching Opportunity for a quick visit. It would be their only chance since once the rover descends into Perseverance Valley, she won’t be coming back this way again. “Our estimate was that it would take a month to go to Winnemucca, look at it, kick around, and get back,” said Golombek.

Ultimately, the decision was – no go. With solar conjunction coming up in July and then winter following a few months after that, along with the scientists’ desire to get some serious research completed inside Perseverance before the brutal freeze grips the rover and the landscape, time was not on their side. “The highlight of the extended mission proposal was going down into the valley, so that’s what we’re going to do,” Golombek summed up.

The Winnemucca study however is “a work in progress,” said Arvidson. “We did Pancam 13-filter of it and also super resolution, where we keep taking Pancam images, which allow us to sharpen the spatial resolution. We’re using the CRISM data now to see if we can help identify whether it’s something special mineralogically.” The bright material may turn out to be simply dust. “But right now, we’re just not sure.”

Opportunity moved on, turning her cameras and scientific attention to the Martian ground before her. This was as good as any a time to inventory the terrain, complete with its pebbles and stones, and so on Sol 4692, (April 5, 2017), the robot began taking images needed for what the scientists call a color clast survey.

“Every now and then we look in the foreground with the Pancam in monochromatic or color or 13-filter and image the clasts, the little rocks and pebbles sitting on the ground,” said Arvidson. “It’s characterizing what we’re sitting on and driving on as opposed to a specific target that we’re driving to.”

Opportunity put 14.11 meters (46.29 feet) in the rear view mirror on Sol 4693 (April 6, 2017), wrapped the first week of the month taking some more images for the color clast survey, and then drove into the second week of April on Sol 4695 (April 8, 2017), logging 41.94 meters (137.59 feet). It was a drive that put her within 350 meters (about 0.22 mile) of the valley or about halfway there from her Rocheport-Cape Tribulation departure point.

The robot field geologist continued the color clast survey on Sol 4696 (April 9, 2017), and the next sol, 4697 (April 10, 2017) used her Microscopic Imager (MI) to take close-up pictures of an exposed outcrop within reach, a target the team named Julesburg. Following the routine science protocol, the robot then placed her APXS on the outcrop target to analyze its chemical composition, work that she would continue the following sol.

“We couldn’t brush Julesburg, so we bumped to another target we called Ogallala,” Arvidson said.

On Sol 4699 (April 12, 2017), “Opportunity basically turned .57 meters (1.87 feet) to approach and position the Rock Abrasion Tool (RAT),” said Nelson. And the next sol, 4700, the robot successfully used her RAT to brush Ogallala. When the rover deployed her Instrument Deployment Device (IDD) the sol after that however, she experienced an unexpected .4 degree in tilt.

The ops engineers and RPs are still not sure why, when, or how it happened. “This occurred at a time when we weren’t taking data, so we don’t see it,” said Nelson. “The best guess is that perhaps thermal expansion or contractions maybe caused the wheels to slide off a little rock.”

As the third week of the month began, Opportunity and her ground crew conducted some diagnostics on the IDD on Sol 4702 (April 15, 2017). “Those showed no problem and we were stable at that point,” said Nelson. “We did a couple of ‘touches’ and different preloads with the IDD instruments to see if anything moved,” he added. “Nothing did.” All’s well that ends well.

The rover spent the next sol taking care of routine engineering and science business and preparing to grind into Ogallala. And on Sol 4704 (April 17, 2017), that’s just what the rover did, successfully shearing off the top layers.

“This was Opportunity’s 51st RAT grind on Mars and the first grind in 334 sols, the last one occurring on Sol 4370 (May 9, 2016) back in Marathon Valley on target Pierre Pinaut 3,” reported Stephen Indyk, Senior Project Engineer, of Honeybee Robotics, Spacecraft Mechanisms Corporation, who has been overseeing Oppy’s RAT action.

“Ogallala was a very shallow grind on a flat, but rough textured surface to a depth of 0.8 millimeters,” Indyk noted. “The science team was content with the amount of scientific data collected at this target and decided to drive on.” The RAT, meanwhile,” he added, is healthy and continues to operate nominally.”

“We didn’t grind too much into it,” said Arvidson. That’s because it wasn’t what they thought it was. The scientists had been hoping this was Burns Formation, the sulfate sandstone outcrop ubiquitous in Meridiani Planum and wanted to characterize it locally to compare with the Burns outcrops they plan on looking at in the bottom of the valley. “But it’s not Burns,” said Arvidson.

What Ogallala is, the scientists cannot yet say for sure. It’s either a part of the Shoemaker Formation breccia hurled up and formed around the time of the impact that created Endeavour occurred 3.7 to 4.2 billion years ago. Or perhaps, it is Grasberg Formation, the terrain that formed after the impact, which the rover first uncovered at Cape York.

“It seems to be most akin to Grasberg, but it doesn’t have the exact composition of a Grasberg,” said Arvidson. “We have multiple observations, so we’re still trying to work it out. But it’s definitely not part of the Burns Formation.”

“We haven’t seen anything that looks like Burns yet, since climbing down the wall of the crater,” Golombek added later.

The next sol, 4705 (April 18, 2017), Opportunity took off and chalked up her long-distance sprint of the month, 131.99 meters (about 433.03 feet). “The longest drive in terms of distance was around 219 meters, which Opportunity set years ago,” said Stroupe. “So this a long way from being a record, but it’s certainly the longest drive we’ve done in two, three years at least.”

The rover took a brisk jaunt the following day, completing 19.24 meters (63.12 feet) on Sol 4706. “We’ve been getting some spectacular views,” said Stroupe. Still, there was no clear view of the head of the valley yet.

Behind the scenes on Earth, talk turned to Perseverance Valley, how it may have formed and what it is, geologically speaking, generically, specifically, and in the evolving glossary of Mars geology terms. “It goes to definitions and ‘Geologese,’” said Golombek.

For years now, what was recently named Perseverance Valley has been referred to among MER team members and in these ‘pages’ as an ancient gully. And by the long-held, broad definition of the word ‘gully’ on Earth, provided the rover and the scientists find evidence for past water, it will continue to be accurate geologically to call it an ancient gully.

“On Earth, the word ‘gully’ is relatively broad, defined as a water-worn channel or an incised channel typically thought of as carved by water,” said Golombek. “On Mars, the word is being used these days in a different way. The way people look at gullies on Mars now is much more specific than the Earth definition.”

The evolution in the definition of the word on began about 17 years ago when Michael Malin and Ken Edgett, of Malin Space Science Systems (MSSS) in San Diego, announced their discovery of very small gullies on Mars in Science magazine. They found these features, the smallest features then ever observed from Martian orbit, with imagery from their Mars Observer Camera [MOC] onboard Mars Global Surveyor.

“We didn’t know there were gullies of this [small] scale until Malin-Edgett discovered them in MOC,” noted Golombek. And from this discovery, gullies on Mars garnered a revised, specific description, unlike the broad definition long used to describe your basic gully on Earth.

During a recent MER end-of-sol meeting, Tanya Harrison, a “newly minted” PhD (University of Western Ontario, Canada) who wrote her doctoral thesis on mapping gullies on Mars, reviewed the refined definition in a discussion about Perseverance.

“The definition for a gully on Mars right now, from the Malin-Edgett 2000 paper, is that it have three features: an alcove; a channel; and an apron or depositional fan at the end,” Harrison told the MER Update. It also implies “a geological youthfulness,” meaning a gully has to have developed at some point in the last tens-of-thousands to hundreds-of-thousands of years, added Harrison, a new member of the MER team who has been working as a researcher at Arizona State University (ASU), under Jim Bell, Planetary Society President and lead scientist of the MERs’ Pancams.

Because of their youthfulness, “you tend not to see a lot of craters around gullies,” she pointed out. “The other tricky thing is if you look at what we classify as gullies on Mars now, you usually don’t see one just hanging out by itself. They usually cover an entire slope.”

Indeed, from what the eye can see in the overhead images, Perseverance Valley is one feature, on its lonesome own. There are no similar channel-like features nearby, and there are superimposed craters. “It’s hanging out in this one place at a latitude where we don’t see any gullies. That seems a little odd,” said Harrison, who was recently appointed Director of Research at ASU’s NewSpace Initiative. “It’s a different beast. It’s Noachian.”

“Our gully is definitely not youthful. It is ancient,” underscored Golombek. “Which is why we call a valley. It has no upper catchment. It goes directly from the plains on the upper end, so it fails that part of the current ‘gully’ definition. It has no fan deposited at the bottom, and other stuff has been put on top of it. So in that regard, it also fails the current definition. All of our investigations so far show that Perseverance doesn’t have many of the same features that planetary scientists typically use these days to define gullies on Mars.”

Gullies have been a hot topic of study for more than a decade because of the Malin-Edgett discoveries, the newly revised definition and the youthfulness it imparts, along with the notion that these gullies could indicate sources of liquid water at shallow depths.

That notion has taken such hold that “using a word like ‘gully’ has this implication that water is involved,” said Harrison. And with Planetary Protection measures in place, only sterilized spacecraft could be granted a ticket to visit a potentially habitable, watery environment, a place where Martian microbes, theoretically, could emerge.

While it is possible, probable even that there were gullies – or “small valleys or ravines originally worn away by running water,” as originally defined – back in the Noachian days of Martian antiquity, there is no water at Endeavour today. Thus, “Perseverance is not a gully according to the definition of ‘gully’ as used on Mars today,” said Golombek.

And so Perseverance’s reality, kind of like Pluto’s, is that it no longer precisely fits the more narrow, refined definition that has taken hold in the last two decades as the Mars glossary has been tweaked. “That doesn’t mean Perseverance is not a water-worn channel – and that’s the thing we hope to understand,” Golombek clarified.

“Regardless of what you call it, ancient gully, valley, gulch, ravine, you can come up with a thousand names, the question is – how did it form?” Golombek reiterated. “That is our objective. What matters is whether we can determine if this feature was water-carved, and if it was, determine if it was prominently liquid water, like a stream or lake coming over the edge. Or, was it a mudflow, hyper-concentrated liquid slush with sediment? Or was it a dry avalanche? We can test these hypotheses,” he said.

From the angle of the slope, the MER scientists are leaning away from the dry avalanche theory. But there is plenty of research in the field to be done. For now, this much is certain: Mars has handed MER another mystery.

Opportunity logged 63.33 meters (207.77 feet) on Sol 4708 (April 22, 2017). Two sols later, on 4710 (April 24, 2017), she put another 35.69 meters (117.09 feet) in the rear view mirror. The rover stopped just to the east of a small crater the team named Orion, in honor of the Apollo Lunar Module that landed on April 21,1972 at 02:23:35 UTC. “It was a Jim Rice special,” noted Arvidson, crediting Rice, a MER Science Team member, and his “historic memory” for the naming suggestion.

“It was cool to pull up next to a hole in the ground like that and be able to look into it,” said Seibert.

After a sol of taking in the views and recharging, Opportunity was reminded once again that what you don’t know can stop you in your tracks. On Sol 4712, the rover suffered an SEU, a single event upset. “We get these occasionally,” said Nelson. “This one stopped the motor at the end of a drive step. Nothing happened. It was benign and seems to have had no real impact on things. We just picked up on the next drive step and continued on.”

It was probably an errant cosmic ray that hit the Field Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs). “Our electronics are radiation hardened but the FPGAs that control the motors are not as rad-hard as most of the rest of the electronics, “ said Nelson. “So we need to constantly recheck those.”

The team planned for the rover to drive on Sol 4713 (April 27, 2017), but when they realized the downlink would be less than they thought, “we didn’t drive,” said Seibert. “We decided to hold off and image Orion and another small crater nearby and take the next drive over the weekend,” elaborated Golombek.

Opportunity departed April on Sol 4716 (April 30, 2017), the way she entered it – driving. She put 40.39 more meters (132.51 feet) on her odometer to rack up a total of 388.44 meters (0.24 mile) for the month.

For the RPs, the driving in April was something like putting the roof down on your convertible and driving up the old Coast Highway with the wind blowing through your hair. “It has been really nice,” said Stroupe. “Lately, we’ve been able to drive without using Visual Odometry and it’s been years since we’ve done that too. It’s been really great.”

The days of doing these long drives are not going to last long. “We know it’s short-lived,” said Stroupe. “We know that once we get into Perseverance Valley, the terrain is going to change dramatically.”

As Opportunity carries on with the next assignments on Mars, the MER ops team on Earth is planning for solar conjunction which begins near the end of July, and soon thereafter will begin planning preparations in coming weeks. Most of the MER ops team has been through solar conjunction and the winter preparedness drill numerous times. They know how to pace the rover and themselves. They know Mars will continue to throw surprises. And the plan is – they will be ready.

Winter Solstice in the southern hemisphere of Mars arrives November 19th. This will be the mission’s eighth Martian winter and the team wants the rover to be able to work through it. Opportunity, as usual, seems up for the challenge.

“The rover is performing beautifully,” said Golombek. “We have seen no degradation of the wheels or motors currents or anything onboard. It’s functioning fantastically and has all of the capability needed to be able to investigate Perseverance Valley.”

While it is a one-way path into Perseverance Valley, Opportunity has plenty of places to go and things to find when this work is finished. In fact, MER RP Bellutta has already charted an exit for the robot field geologist to take out of the crater rim when her work in Cape Byron is done.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth