A.J.S. Rayl • Apr 28, 2006

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Spirit Pulls up to Winter Home as Opportunity Races to Victoria

Two years and 3 months after they bounced to landings at Gusev Crater and Meridiani Planum, the Mars Exploration Rovers are heading into their second, long cold Martian winter.

Although Spirit had to divert from the planned, uphill route to McCool Hill this month because of excessively sandy terrain, the rover did make its way to a north-facing slope at a locale called Low Ridge Haven where it is currently basking in the Sun. This is where it will spend the winter, which on Mars means the next 8 months or so, doing in-depth research on targets in the immediate vicinity and nearby surroundings.

Meanwhile, on the other side of Mars, Opportunity has been putting the pedal to the metal, making fast tracks to its winter destination, Victoria crater, and is currently more than one-third of the way there from its last major research stop, Erebus crater.

As winter sets in, the Sun is crossing lower and lower in the northern Martian sky with every passing day and power -- or fear of a lack of power -- has been an issue for the mission. The available amount of solar power on which the rovers rely will keep dropping until the shortest day of winter, or winter solstice, passes in mid-August. To keep producing enough electricity to conduct their science assignments and to run overnight heaters that protect vital electronics, the rovers' solar panels must now be tilted toward the winter Sun so they can soak up as much sunlight as possible. The winter temperatures on Mars can drop to 191 degrees below zero Fahrenheit at some places and will certainly drop well more than 100 degrees below zero where the rovers are. "But temperature is not the problem," rover principal investigator Steve Squyres, of Cornell University, pointed out. "It's really the solar flex that's the issue."

For Spirit the situation had become critical. In fact, there had been some concern earlier this month as to whether Spirit was going to survive the season. "We were a little nervous for a while," Squyres told The Planetary Society in an interview yesterday. "Now that we're on this 11-degree northward tilt, we're feeling good about survival."

Opportunity's position at Meridiani, which is closer to the equator than Spirit's position, allowed that rover to get enough sunlight to maintain good levels of power output, usually around 450 watt hours. "Opportunity is sitting almost spot on the equator; whereas Spirit is about 15 degrees south," noted W. Bruce Banerdt, the new MER project scientist, of JPL. Banerdt replaces Joy Crisp, who is moving on to the Mars Science Laboratory mission. "In Earth terms, that's still about the latitude of Guatemala, so we would think of that as being pretty tropical," he said. "But these machines were designed to operate within a fairly narrow range of illumination, because they were only supposed to last 90 days."

Spirit and Opportunity, however, have lasted 8 times their 3-month "warranties," defying the odds time and again. Together, the rovers have so far returned more than 150,000 images, and each has driven more than 6.8 kilometers (4.2 miles) or 11 times the original distance planned. Of course, the signs of aging on the dynamic duo are obvious now. Spirit's right front wheel is gone for good; Opportunity's instrument deployment device (IDD) remains "arthritic" and one of its steering motors has failed. Nevertheless, Spirit and Opportunity are still working every day, every instrument on both rovers is still active, and overall, rover health is, Squyres reported, "pretty much unchanged."

Spirit from Gusev Crater

After finishing up work at Home Plate in March, Spirit headed onward through the Inner Basin at the Columbia Hills in Gusev Crater, toward the north-facing slopes of McCool Hill and an area dubbed Korolev, where the team planned to have the rover spend the winter. Named for Willie McCool, one of the 7 astronauts who lost their lives in the Columbia space shuttle disaster, McCool Hill as it turned out was recently found to be the tallest of the seven hills in the Columbia Hills at Gusev. On Sol 779 (March 13, 2006), as the rover was pulling away from the Home Plate area, one of the 10 motors that operate its six wheels broke, rendering the right front wheel useless.

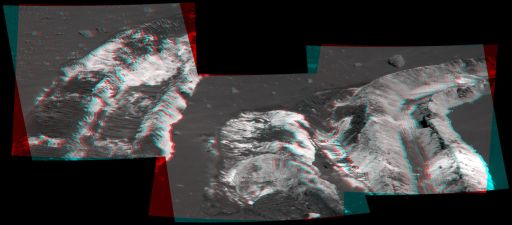

Bright soil churned up rn route to McCool in 3-D

Bright soil churned up rn route to McCool in 3-DPut on your 3-D glasses for full immersion. While driving eastward toward the northwestern flank of McCool Hill, Spirit's wheels churned up the largest amount of bright soil discovered to that point in the mission. The rover took this image with its PanCam on Sol 788 (March 22, 2006). It shows the strikingly bright tone and large extent of the materials uncovered. Several days earlier, the rover unearthed a small patch of light-toned material dubbed Tyrone, which strongly resembled two patches of light-toned soils discovered earlier in the mission: Arad, discovered on the basin floor just south of Husband Hill in early January 2006, and Paso Robles, found in 2005 while the rover was climbing Cumberland Ridge on the western slope of Husband Hill, both of which boasted a salty chemistry dominated by iron-bearing sulfates. The rover examined its most recent, light or white-toned discoveries up close with its PanCam and mini-TES, and researchers will compare its properties with the properties of the other deposits. These discoveries seem to indicate, however, that salty, light-toned soil deposits might be widely distributed on the flanks and valley floors of the Columbia Hills region in Gusev Crater on Mars. The salts, which are easily mobilized and concentrated in liquid solution, may record the past presence of water, but so far these enigmatic materials have generated more questions than answers. This stereo view combines images from the two blue (430-nanometer) filters in the PanCam's left and right "eyes." The image should be viewed using red-and-blue stereo glasses, with the red over your left eye.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

Spirit had an earlier problem with the same wheel system just five months after landing in January 2004. In that situation, it was a lubricant issue. The engineers directed the rover to drive backward to redistribute the lubricant, which returned the wheel to normal operation. This time, however, the open connection the engineers found meant they could no longer use that motor, and hence that wheel. Since then, Spirit has had the burden of having to drag its right front wheel. "The way the wheel failed is that it's locked, so it doesn't spin freely, and has to be dragged," explained Banerdt. "It's like steering a shopping cart in the store when you get one with a stuck wheel that keeps pushing over to one side.

The day after the motor broke, the rover logged one really good drive day, driving for 10 meters (33 feet). But in the days following that, and as March gave way to April, Spirit encountered slippery terrain, which, combined with the uphill route to McCool Hill, ultimately proved to be too much. On Sol 799 (April 2, 2006), the rover successfully backed out of a particularly sandy area and roved 5.8 meters (19 feet) to firmer ground.

"We were having trouble getting over to McCool because of the wheel getting stuck and there were some areas with loose regolith between us and that hill that we were getting bogged down in and so were not making much progress," Banerdt said. Making matters more intense, the rover's energy had fallen to around 330 watt-hours, getting too low for comfort. The MER team decided to change the plan and direct Spirit to a closer, north-facing slope in a smaller area they dubbed Low Ridge Haven, located to the north and west of McCool Hill. Ever resilient, the rover persevered and headed back downhill and over toward its new destination just about 20 meters away.

The concern about Spirit's survival was deeply felt, Banerdt said, because of the combination of the loss of the right front wheel and the power issue. Driving on 5 wheels and having to drag the 6th wheel took some getting used to. "If we hadn't been able to learn very quickly how to drive the rover with 5 wheels, we could have been in trouble. We're not joy-sticking these things, so we have to send the commands up and wait until the next day to see what happened. As a result, we had to do a lot of testing in the sandbox and some very quick analysis to figure out how to make the rover drive in the direction we wanted and to get it in the configuration where it would make the best progress," he explained. "Until we did that, there was definite concern. The fear was we would actually get bogged down and after a few more weeks would get to the point where the rover would not have to shut down, but would no longer have enough energy to do any significant driving. And at that point, we would be stuck, and with the Sun going lower in the sky, we could have been in a bad situation. That's what was worrying everybody."

In the end, it all worked out and with new direction from the team Spirit once again overcame the challenges. "By analyzing the terrain, we found an area that was much closer and had a more traversable path to get to," Banerdt said. "The engineers tend to be the worry-warts about these things, because the possibility of things going wrong are pretty dire. But they put together a plan to get to a place that was closer and more accessible than our original plan and we were able to get there several days before our pessimistic estimates had indicated."

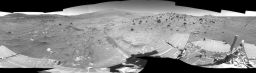

Low Ridge Haven

Low Ridge HavenSpirit acquired the images in this mosaic with the navigation camera on Sol 807 (April 11, 2006). Approaching from the east are the rover's tracks, including a shallow trench created by the dragging front wheel. On the horizon, in the center of the panorama, is McCool Hill.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

In fact, it was less than a week later, on Sol 807 (April 10, 2006), that Spirit roved onto Low Ridge Haven. The rover promptly perched itself at a favorable 11-degree tilt toward the north and began basking in the Sun. The effort paid off almost immediately as the rover's power output increased by 50 to 60 watt hours per sol to around 390 watt hours. The team heaved a collective sigh of relief. Still, that is less than half of the levels upwards of 800 watt hours that the rovers have enjoyed since landing in January 2004, thanks in large part to dust cleaning events caused by little gusts of Martian winds that have from time to time blown dust off the rovers' solar arrays. Neither rover, however, has had such a cleaning event in a long, long time -- about 260 sols for Spirit, and some 160 sols for Opportunity.

"It's certainly wintertime now and the energy is not generous by any stretch, but we're comfortable with the energy values we're seeing now and we're able to get lots of science done," said Squyres.

"We can [wake] up and do the usual housekeeping and engineering, the things that keep the rover healthy, communicate with Earth, and still have enough energy left over to do about an hour of science every day, and we don't have to shut the rover down and go into DeepSleep, which is actually a pretty nice situation to be in," elaborated Banerdt. Since arriving at Low Ridge Haven, however, the energy has been dropping as the rovers head deeper into winter. The rover's position also serves to maximize the robot's ability to communication with Mars Odyssey, which will only help as winter progresses. The projections contend that Spirit will hit a low of around 280 watt-hours at winter solstice in mid-August.

Despite low energy and its uphill and downhill tribulations early in the month, Spirit still managed to turn in science fieldwork almost every day, including various atmospheric remote sensing observations, as well as targeted remote sensing studies, and mini-thermal emission spectrometer (mini-TES) and panorama camera (PanCam) observations of nearby targets and surroundings.

As the rover pulled into Low Ridge Haven, it used its navigation camera and PanCam to take high-resolution images of the immediate terrain, surroundings, and specific targets, all of which the team decided to name after Antarctic explorers and research stations. In the ensuing days, Spirit examined rock targets Marambio and Orcadas with its mini-TES and took images of another target dubbed Maitri with the PanCam.

Spirit's current location at Low Ridge Haven is about 60 meters (197 feet) from the slope break at the foot of McCool Hill, according to Banerdt, and about 100 meters (328 feet) from the original location, Korolev, at McCool Hill where the team originally planned to spend the winter. For those who may assume that the rover will now hunker down for the winter and try to ride it out coasting, so to speak, exerting as little effort as possible, think again -- these are the Mars Exploration Rovers. "There's going to be a lot of work done and in particular we're going to finally get the chance to do a bunch of things that the rover is capable of but that we've never had a chance to do before," Squyres pointed out.

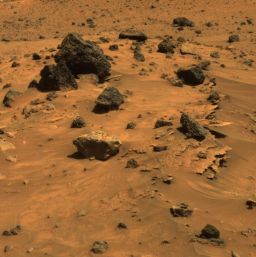

Rocks at Low Ridge Haven

Rocks at Low Ridge HavenIt doesn't get any more Martian than this. At least three different kinds of rocks await scientific analysis at Low Ridge Haven, where Spirit will likely spend the 8 months of Martian winter. Each type is visible in this picture, which the rover took with its PanCam on Sol 809 (April 12, 2006): paper-thin layers of light-toned, jagged-edged rocks protrude horizontally from beneath small sand drifts; a light gray rock with smooth, rounded edges sits atop the sand drifts; and several dark gray to black, angular rocks with vesicles (small holes) typical of hardened lava lie scattered across the sand. This view is an approximately true-color rendering that combines images taken through 3 of the PanCam's 13 filters. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

Although Spirit will be sitting in one place, the science team has put together a winter science campaign that is "extremely ambitious and has a lot of potential to tell us a lot of interesting things," added Banerdt. "We have several different kinds of rocks within the work volume that we can analyze and that look different than things we've done before." Moreover, having to drag its right front wheel may, however strangely, turn out to be a kind of fortuitous mishap for this rover in the mission. As Spirit has trudged along, the dragging of the wheel churned up the topsoils and revealed some very white, sticky appearing, powder-like stuff underneath as well as other materials with "very strange properties," said Banerdt. "As we're dragging this wheel we're plowing a furrow and it's plowed up this puzzling white material that we'll now have a lot of time to analyze with our Mössbauer and APXS."

Spirit is into the winter campaign now, informed Squyres, and having the time to actually do real in-depth studies is something the team is enthusiastically welcoming. "The first phase of the winter campaign consists of two sets of activities: one is acquiring what's probably going to be the biggest panorama we've ever done, the McMurdo pan. That's going to be all 13 filters -- all the colors we've got -- and for a number of filters it will be uncompressed data, so it'll be extremely high resolution." The mosaiced panorama will ultimately be comprised of some 1,500 images that will take weeks to acquire and weeks to dowload, he added, "but it's going to be a really remarkable dataset." In adtion to being something for all human eyes to behold, these and other PanCam images will provide important information about the nature and origin of surrounding rocks and soils in this area of Gusev Crater.

The second part of the first phase of the winter campaign is an in-depth study and analysis with the IDD on the soil directly in front of the rover. "It will include a number of things, probably the most interesting one is that we're going to conduct progressive soil brushing," Squyres said. "We'll make measurements with the alpha particle x-ray spectrometer (APXS) and Mössbauer spectrometer and then use the RAT to brush away several millimeters of soil and take more measurements and then brush away several millimeters of soil and do it again." At each level, Spirit will measure the mineral and chemical properties and assess the physical characteristics, including grain size, texture, hardness, of the material, using the instruments on the IDD. This kind of in-depth study will, Squyres explained, "give us a detailed several millimeter-scale stratigraphy of chemistry and mineralogy in the soil." Of particular interest are vertical variations in the soil characteristics that may indicate the presence of past water.

Spirit will also devote some time to studying the mineralogy of the surrounding terrain using the mini-TES, searching for surface changes caused by high winds, and monitoring atmospheric changes. On Sol 809 (April 12, 2006), the rover deployed its IDD for the first time since the week of Sols 769-772 (March 2-5, 2006) when it conducted close-up examinations of targets around Home Plate. This time, at its new winter home, however, it acquired images of a target dubbed Halley with its microscopic imager (MI), and completed overnight observations with the APXS and took PanCam images of targets Troll and Mirny.

"We found some very strange results," Squyres said. "Halley has a very high hematite concentration and the highest zinc concentration we've ever seen anywhere on Mars." The target is not outcrop, but Squyres wasn't saying exactly what it was. "I'm not ready to go out with details on this one yet. It's a target with a lot of hematite and zinc and we're still trying to figure it out."

According to the current plan, Spirit will be at Low Ridge Haven for the duration of the winter season, although its stay ultimately depends on the rate of dust accumulation on the solar arrays and whether the rovers have any cleaning events. "The power story is the result of both dust and where the Sun is in the sky," Squyres reminded. "While we can predict where the Sun will be in the sky, we can't always predict what the dust is going to do. So we'll see, but 8 months is not an unreasonable guess."

After the winter solstice in August, once Spirit finishes the first phase of its winter campaign and depending on energy levels, scientists may direct the rover to pivot around the disabled, right front wheel to get different targets within reach of the arm and move onto the second phase of the winter campaign. "In the second phase, we will probably do some maneuvers with the rover," Squyres confirmed. "There's a very nice outcrop of finely layered bedrock just a meter or so away from our current location that we should be able to turn to and do some very in-depth investigations on that as well."

"We've had these ideas for things like this -- progressive soil brushing, a really good 13-filter PanCam mosaic -- for a long time," Squyres continued. "The problem is that those things take a long time to do and we haven't had the luxury. Even before we got to the summit of Husband Hill, we've been rushing through everything we do -- every bit of science -- Home Plate, El Dorado, Comanche, Seminole, Haskin Ridge, everything has been done at a high speed rush because of the fact that we had to get to a good north-facing haven for the winter. While I don't feel that we short-changed the science, we certainly have had many of investigations be more abbreviated than we would have liked them to be and we were forced into that by circumstances. We're finally at a situation where we can stop and really do science in detail.There's no imperative now to rush, rush, rush, and get off to the next spot as quickly as we can. We are really shifting gears considerably and doing really in-depth science investigations, more in-depth investigations that have ever been done with either rover."

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

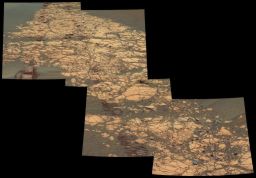

A paved path for Opportunity

A paved path for OpportunityAs Opportunity continues a southward trek from Erebus Crater toward Victoria Crater, the terrain consists of large sand ripples and patches of flat-lying rock outcrops, as shown in this image. Whenever possible, rover planners keep the rover on the outcrop "pavement" for best mobility. This false-color image mosaic was assembled using images Opportunity acquired with its PanCam on Sol 784 (April 8, 2006) just before Noon local solar time. This view shows a portion of the outcrop named Bosque, including rover wheel tracks, fractured and finely-layered outcrop rocks and smaller, dark cobbles littered across the surface.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

At Meridiani Planum, Opportunity has been following its prime directive -- to drive. Since completing its study at Payson, the last outcrop at Erebus crater that the rover examined, driving has been consistently at the top of the agenda. During the first week in April, the rover, averaging about 430 watt-hours of energy output this month, logged some 170 meters (558 feet) on the way south to Victoria. We're making good progress," said Squyres. "We have about 1400 meters (1.4 kilometers or.86 mile) to go and are driving every day."

The scenery, Squyres noted, has been beautifully Martian -- rows and rows of really large ripples interrupted by splotches of outcrop. "It's been really striking, but that's not necessarily good news," he said. "What we're seeing are big outcrops of bedrock that have some topography to them and we're seeing some big, big drifts," he said. "We're doing fine and making our way through it all. What's saving us here is that the grain runs north-south and we're heading south. If we were trying to go across instead of with the grain, it would be really tough, but we're making good progress. Everything is holding together and all 6 wheels are working. In a way it sort of feels like some of the dashes we've done in the past with Spirit, where we're trying to just cover a lot of ground."

Opportunity is logging "anywhere from 70 to 100 meters" every week now toward Victoria, Banerdt added, and along the way the rover has taken images with its navigation and PanCam, and conducted mini-TES observations of the sky and ground, as well as conducted some atmospheric remote sensing. Still, the rover is not doing much stopping for science. "We're doing the best we can to survey the bedrock along the way, stopping occasionally to make measurements with the IDD but the real prize is Victoria," Squyres said. "The rover is a wasting asset and the thing to do is to get there as fast as we can, so we're driving really hard with Opportunity."

As April progressed, Opportunity veered to the southeast to avoid a large dune field due south and by Sol 788 (April 12, 2006) was more than one-quarter of the way to Victoria from Erebus. For the most part, the rover's routine in recent weeks has been one of driving during the week and doing IDD work on bedrock and drifts on the weekends. "That's because we can't plan drives for everyday of the weekend because we don't have data on Friday that we need to plan to plan multiple drives so weekends are when we tend to do IDD work," Squyres explained.

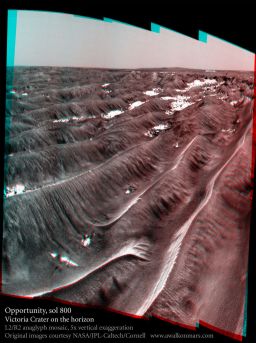

Victoria crater on Opportunity's horizon

Pull out your 3-D glasses for full immersion. Opportunity took the images used in this mosaic with its PanCam on Sol 800, when it was still more than a kilometer away from Victoria crater. The image has been stretched vertically to exaggerate the topography and emphasize the shape of the rim of Victoria crater on the horizon. Victoria crater is 800 meters in diameter, 6 times the size of Endurance crater. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / Nico Taelman

Even so, Opportunity is unstowing its IDD after every drive. "The old policy was that the IDD is something we could wear out by over-using it and so we were only deploying it when we have an important science target in front of us," said Squyres. Then, the problem with the shoulder joint occurred where the wire broke inside the motor. That means, basically, the motor could fail at any time. "There are 2 different causes you could imagine for an IDD failure: one class results from too much use -- you move something too many times and it wears out so each time you move it, you're costing yourself something, but if you don't use it you are preserving your resource; a second cause of failure results simply from the passage of time whether you use the device or not," Squyres explained. "These causes are distinct from one another in a very important way, because if the second cause is the kind you're talking about, then you want to use it as much as you can because you're going to lose it eventually. You're not worried about it wearing out, but [you are worried about it] dying as a consequence of the passage of time. The failure we had in the shoulder joint fell into that second category -- it was simply the passage of time, too many thermal cycles," he explained.

In effect then, since Opportunity left Olympia, the policy of not using the IDD except for high-priority targets has changed. "We are using the IDD almost everyday, because we don't want to keep it stowed," said Squyres. "If it fails while it's stowed, then we'll never be able to unstow and the whole IDD is gone. So what we want to do is have it unstowed most of the time, so what we do every single drive -- we stow the arm and then after the drive is unstow the arm."

The directive for May for Opportunity remains the same: rove on to Victoria. If everything goes as planned, the rover will reach its destination well before the depths of winter take hold. Even then though, Banderdt said, the team projects that Opportunity's energy levels will only drop to a low of around 350 by winter solstice.

While Opportunity found evidence at Erebus crater of a "thicker, wetter sediment" that any before seen on Mars, as Caltech's John Grotzinger, a member of the MER team, put it, Victoria beckons with promises of so much more. With a diameter of 800 meters (half a mile), Victoria boasts a much thicker sequence of exposed sedimentary rocks.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth