A.J.S. Rayl • Mar 31, 2009

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Spirit Breaks Rove Record, Opportunity Sees Endeavour's Distant Rim

The Mars Exploration Rovers logged a memorable March, with Spirit finally making some serious tracks and setting a new driving record for a five-wheeled rover, and Opportunity getting a first glimpse on the distant horizon of its next big attraction, Endeavour Crater as it crossed a geologic boundary into a new field of "blueberries."

"Spirit's roving and that’s the big event this month," said Steve Squyres, of Cornell University, principal investigator for the rovers' science instruments. "It feels so good to see new scenery on the front windshield for a change."

“Spirit is boogying,” added Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis, the deputy principal investigator for rover science, who usually directs Spirit’s science meetings, while Squyres normally handles that responsibility for Opportunity. “I wanted to play Willie Nelson's ‘On the Road Again’ in the SOWG [science operations working group] meeting,” he said, “but I didn't have time to download it.”

With the 40th annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference going on in Texas last week, it was as busy a month for the scientists on the mission as it was for Spirit and Opportunity on Mars.

At Gusev Crater, Spirit, after weeks of trying to rove up the slippery, sandy slopes of Home Plate’s northeastern edge, was finally directed by the MER team to change course this month and take the long way around the circular plateau to get to its next destinations to the south. "After several attempts to drive up-slope in loose material to get around the northeast corner of Home Plate, the team judged that route to be impassable,” said John Callas, of JPL, MER project manager.

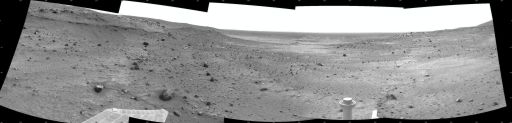

Before embarking on its new route, however, Spirit had to get away a troublesome little rock that was threatening to stop it in its tracks. Once it escaped that potential danger, the intrepid rover bolted big time, putting 25.82 meters on its odometer. That’s the longest drive Spirit has put on its rocker bogie frame since its right front wheel broke back in March 2006.

Spirit followed that record breaking dash with more long drives, including an approximate 22-meter jaunt last Saturday. “These long drives really are the story of the month and we are all excited about that,” said Sharon Laubach, the integrated sequencing team chief for the mission, of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where the twin robot field geologists were built and are being managed.

Edgar Allen Poe

Edgar Allen PoeSpirit took this picture of soil it turned up with its panoramic camera (Pancam) on its Sol 1852 (Mar. 19, 2009). It not only reveals the darkest soil this rover has uncovered to date, but, offers up "some of the most stunning color diversity of any little patch of Martian real estate ever seen," as Pancam principal investigator Jim Bell puts it. The dark soil, however, inspired its name.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell University

Those long drives took Spirit to the other side the northern part of Home Plate to the mouth of the West Valley. The team hopes the rover will be able to chart a course through this valley to the south and Goddard and von Braun, the house-sized pit and intriguing mound that the team has long hoped Spirit will get to study up-close. But the western route is by no means a “slam dunk,” Squyres noted. “It is unexplored territory. There are no rover tracks on that side of Home Plate like there are on the eastern side,” he pointed out. “But that also makes it an appealing place to explore. Every time we've gone someplace new with Spirit since we got into the hills, we've found surprises."

Surprises, indeed – like the nearly pure opaline silica that Spirit first discovered near Home Plate two years ago, one of the biggest discoveries made so far on the MER mission. That silica-rich material – a sure sign of past water – now appears to be all around Home Plate, according to Steve Ruff, of Arizona State University, the MER science team member who is overseeing the observations and experiments with the miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES). In fact, if having to drive around instead of over Home Plate was a dark cloud for the mission this month, the silver lining is that Spirit, in dragging its frozen right front wheel, has continued to churn up more light-toned soils and nodules that resemble the patches and nodules of ultra-rich silica it found back in March 2007 on the eastern side of the circular plateau.

Just last weekend, the rover uncovered a huge deposit of light-toned soil, in a trough nicknamed Kit Carson. “It’s the most exciting find of the month for sure," said Cornell graduate student Melissa Rice, who has also been on the trail of silica in recent months. She’s been stretching the limits of the panoramic camera (Pancam), under the direction of the instrument's principal investigator and her adviser – and new Planetary Society President – Jim Bell, and using it to identify hydrated minerals from a distance.

In addition to Kit Carson and other samples of light-toned stuff that hint of silica and past water, Spirit churned up a highly unusual dark patch of soil earlier in the month that the team aptly dubbed Edgar Allen Poe. It’s garnered attention not just because it may be the darkest soil seen on the mission so far, but because it also boasts a veritable Martian rainbow of colored soils and as well as little rocks and small clumps. “It’s a spectacular scene, with some of the most stunning color diversity of any little patch of Martian real estate that I've ever seen,” said Bell. The Pancam team is calibrating that data now and starting to explore in quantitative detail all of the different color variations in this place, he said earlier today.

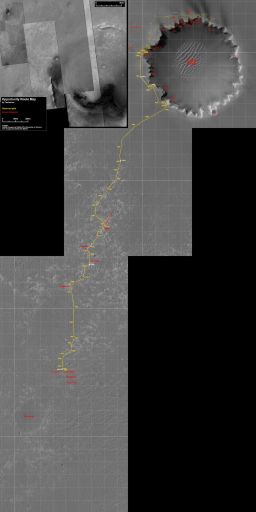

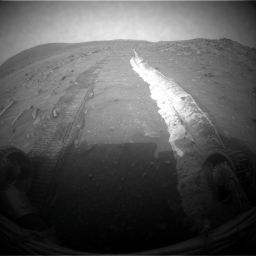

Land ho!

Land ho!Opportunity snapped this image of a northern portion of the rim of Endeavour Crater on the horizon with its panoramic camera (Pancam) on Sol 1820 (Mar. 7, 2009). This portion of the crater's rim is an estimated 20 kilometers (about 12 miles) away from the rover's position west of the crater when it took the image. The width of the image covers approximately one degree of the horizon. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

Meanwhile, on the other side of the planet, at Meridiani Planum, Opportunity caught its first glimpse of the uplifted rim of Endeavour Crater on the horizon with Pancam images that underscore just how valuable and breathtaking the ability to move through an extraterrestrial landscape can be. The images show the rim of this huge crater off in the distance and, by most all accounts, these pictures are “the coolest thing” this month from Opportunity,” as Squyres put it. “It's like we're out in this endless ocean and finally we see our landfall."

Opportunity continued driving mostly backwards in March, because the actuator or motor on its right front wheel has been drawing more than normal current since February. Although this indication of friction within the wheel has forced the rambunctious rover to slow down a bit, Opportunity still managed to pull off some ripping rides during the first part of this month. On its Sol 1818 (March 5, 2009) for example, it cruised for an impressive 80.27 meters (about 263 feet). “She was able to drive that far because of nice terrain where we could see for a good distance," said Laubach. “That made us really happy.”

Endeavour's eastern rim

Endeavour's eastern rimA high point on the eastern rim of Endeavour Crater is visible on the distant horizon in this image Opportunity took with its Pancam on Sol 1821 (Mar. 8, 2009). This portion of the crater's rim was about 34 kilometers (21 miles) away from the rover's position west of the crater when the image was taken. The width of the image covers approximately one degree of the horizon.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

Drives like that are what put Opportunity’s stereo eyes on the prize – and what a prize Endeavour Crater promises to be. At about 22 kilometers (13.67 miles) in diameter, it truly is a gigantic crater, 20 times the size of Victoria. That all but guarantees the crater is harboring ancient Martian secrets in its deepest layers. "Endeavour is still far away, but we can anticipate seeing it gradually look larger and larger as we get closer,” Squyres said. “We had a similar experience during the early months of the mission watching the Columbia Hills get bigger in the images from Spirit, as Spirit drove toward them," he remembered.

Since Opportunity climbed out of Victoria Crater last August, it has driven some 3.2 kilometers (1.98 miles). Still, Endeavour remains an estimated 12 kilometers (7.45 miles) away as the Martian crow might fly, and some 15 kilometers (9.32 miles) on the route charted, which, as Jake Matijevic, chief of rover engineering at JPL, informed this Update previously, avoids potential hazards on the plain.

At the pace Opportunity has been going since leaving Victoria, the MER team estimates that the rest of the trek to Endeavour will take at least a Martian year or about 23 months, Mars willing of course. Still, Callas agreed: "It's exciting to see our destination, even if we can't be certain whether we'll ever get all the way there."

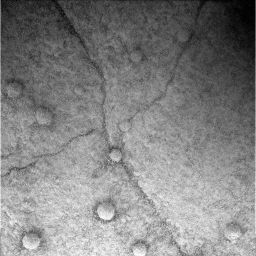

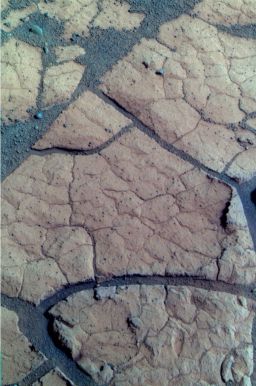

Shortly after snapping those Pancam images of Endeavour's rim, Opportunity made a pit stop for science, at some alluring bedrock the team calls Cook Islands. The rover is currently conducting an in-depth study of that bedrock, which is peppered with “blueberries,” the small spherical concretions – like those the rover found early on in the mission – which boast hematite, the iron oxide that on Earth almost always requires water to form. “We're stopping to taste the terrain at intervals along our route so that we can watch for trends in the composition of the soil and bedrock and boy we found some here," reported Squyres. "Not only do we see spectacular polygonal fracturing in the terrain, the likes of which we haven't seen in a long time, but we're back to seeing big blueberries in the bedrock. This was a surprise.”

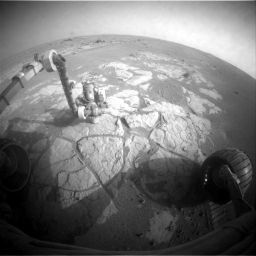

Checking out Cook Islands

Checking out Cook IslandsOpportunity took this image of the Cook Islands outcrop with its front hazard-avoidance camera on its Sol 1826 (Mar. 13, 2009). It shows the rover's robotic arm or instrument deployment device (IDD), extended in preparation of using the alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) to detect the mineral composition of Penrhyn. On the long journey from Victoria Crater toward Endeavour Crater, the rover will be stopping every kilometer or two so that it can "taste" the soil and bedrock. This will allow the science team to determine what trends there may be in the composition of the landscape. This time, the stop is also giving Opportunity time to rest its right front wheel, which has been getting a little hot, because it's drawing higher than normal current.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

Opportunity has been using the scientific tools on it instrument deployment device (IDD) or robotic arm to check out the composition of the Cook Islands bedrock, homing in on a chosen spot called Penrhyn. Using a new workaround for its rock abrasion tool (RAT) for the first time since losing its Z-encoder in January, the rover successfully brushed and ground into the target, then took pictures of it with its Microscopic Imager (MI).

Although this bedrock and soil sampling campaign is part of a planned systematic study of soils and bedrock that Opportunity will conduct every kilometer or two along the route to Endeavour, the stop is giving the rover time to rest its wheel. This strategy of resting has helped reduce the amount of current drawn by the motor in the past and it's already resulted in small improvements. "But the improvements are not quite not sufficient enough yet to change driving direction,” Laubach reported. So once Opportunity hits the Meridiani highway again in April, it will continue driving backwards, at least for a while.

In the meantime, this rover and the team seem to be marveling at the blueberry-fields-forever scene in which Opportunity is currently working and resting its wheels. “Seeing the terrain change, the size of the dunes changing, and the blueberries underfoot – it's so much fun,” said Laubach.

Spirit and Opportunity both passed their monthly physicals with flying colors in March, although dustier skies over Gusev Crater and Meridiani Planum this month led to drops in their energy production. Spirit’s power levels slipped from around 270 watt-hours to about 233 watt-hours, while Opportunity’s levels dipped from around 488 watt-hours to about 315 watt-hours. [Shortly after landing January 3, 2004 and January 24, 2004, Spirit and Opportunity produced around 950 watt-hours.]

Given that it's spring in Mars’ southern hemisphere, the increased amount of opacity or dust in the skies – tau level, as the team calls it – was expected. “It is the season for it,” Laubach reminded. Nevertheless, Spirit is still taking in about 30% of the available sunlight through its dusty solar panels and converting it to power, while Opportunity is utilizing about 50% of the sunlight hitting its arrays.

Spirit snaps dust devil

Spirit snaps dust devilSpirit used its navigation camera to take images that have been combined into this 180-degree view of its surroundings on its Sol 1854 (Mar. 21, 2009). Earlier that sol, the rover drove westward for 13.79 meters (45 fee)t. West is at the center, where a dust devil is visible in the distance. It is spring in Mars' southern hemisphere, th season for winds. North is to the right, where Husband Hill, which Spirit conquered in September and October 2005 dominates the horizon. South is to the left, where lighter-toned rock lines the edge of Home Plate. This view is presented as a cylindrical projection with geometric seam correction.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

The Context Imager (CTX) camera and the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera, also onboard MRO, are also taking images that are helping to forecast and track this event.

Inside word is that there is a storm brewing, but so far it is south of both Spirit and Opportunity. The MER team is keeping watch, of course, with a little help from their friends working MRO's state-of-the-art instruments. While there is concern it could evolve into another massive planet-encircling dust storm, Mars can work in mysterious ways, so only time will tell. But, even if the storm stays to the south, it likely will further increase the atmospheric dust at both Gusev Crater and Meridiani Planum.

The 2007 global dust storm on Mars

The 2007 global dust storm on MarsThis animation -- the handiwork of Glen J. Nagle, the education & outreach manager of the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex in NASA's Deep Space Network -- from images taken by Michael Malin's Mars Color Imager (MARCI) camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter gives an idea of how the storm moved in on and over Opportunity at Meridiani Planum from late June through mid-July, 2007.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / MSSS / animation by G.J. Nagle

The Martian winds that giveth dust, however, also taketh dust away. Gusts, especially during the spring, tend to clear some of the fine powdery material that accumulates on the MERs’ solar panels, thus they have been a key factor in the rovers’ longevity. “We've generally seen the pattern – and we hope to continue to see this pattern – that right before we see a rise in tau, we usually see a cleaning event,” said Laubach. This month, the pattern, she added, was in play. Even Spirit got another “little” cleaning event, which, for this dusty rover, is meaningful.

March also saw both Spirit and Opportunity boot up new flight software, an update to the R9.2 software that has been used on the MER vehicles for nearly two years. Opportunity booted the R9.3 software on March 1; Spirit followed suit on March 27. “This new software is very simple,” Laubach said. It's essentially a patch to address a Y2K problem. “We have some commands that have minimum and maximum time ranges in them and the maximum range was January 1, 2010,” she informed. “Obviously, we're coming up on that, so R9.3 extends the maximum range, to noon on January 1, 2020. If we are still going after that, we'll need to do another software patch." The new, R9.3 software has been working “just fine” on both rovers, she added.

Although the looming dust storm is an obvious concern, the MER team, for now, is "looking forward to an exciting April for both rovers,” said Laubach

In other MER news, Spirit and Opportunity, JPL, Cornell University, and the MER team, earned kudos from Congress this month, when it passed a resolution first introduced in January. On March 10, Congress recognized – for the historical record – the scientific contributions of the twin robot field geologists, commending the team of people that created them and keep them roving. Specifically, the Congressional resolution cited the MER mission’s most notable accomplishments, including the rovers’ travels over more than 21 kilometers of Martian terrain, up hills and down into large craters; their survival through major dust storms and three cold, dark Martian winters; and, of course, their return of more than a quarter million images taken from the surface and scientific findings that early Mars was characterized by impacts and explosive volcanoes, and once boasted Martian environments where water allowed for possible habitable conditions. Hear yea, hear yea.

Spirit From Gusev Crater

After initially making good progress around Home Plate to the east in late February, Spirit struggled incessantly as the calendar flipped to March. During the first week of the month, the rover kept digging in and slipping on the upslope terrain at the plateau’s northeast corner. It just couldn’t seem to get the traction it needed to get back up on top of the circular volcanic formation that it’s been studying for more than two Earth years.

On Sol 1837 (March 4, 2009), the rover planners attempted to have Spirit back down a little, turn and attack the uphill grade with a more cross-slope approach, but it just didn’t work. The rover had difficulty just turning to face a new direction. Because of the soft terrain, it just kept digging in.

On the following sol, Spirit took a bit of a break and checked out some nodules, dubbed HG Wells, after the author who brought us the seminal literary Martian invasion in War of the Worlds. The nodules resembled the silica-rich nodules, named for professional baseball player Gertrude Weise, which the rover found on the east side of Home during the spring of 2007.

Spirit again attempted to conquer the northeastern slope on Sol 1839 (March 6, 2009), but it was not to be. This time, one of its wheels stalled, not a good omen. The rover engineers conducted a diagnostic test to make sure the stall was not an actuator problem. The actuator, fortunately, was fine. So was the terrain – too fine for traction, that is, seemingly reinforcing the futility of attempting further drives in this direction.

But Spirit, as everyone following this mission knows, doesn’t give up unless instructed. So, it made two more attempts to get on top of Home Plate during the second week of March, the first on Sol 1841 (March 8, 2009), the same sol it used its Pancam to take some pictures and check for hydration in some soil it disturbed, called Leigh Brackett. Although the drive failed, the rover did see the silica signature in the disturbed soil target with its Mini-TES.

On Sol 1843 (March 10, 2009), Spirit tried yet again to conquer the modest northeastern slope at Home Plate. “We'd been struggling to get off these little fingers that jut off the northeastern part of Home Plate,” Arvidson recalled. But the loose powdery sand coating the slope ultimately denied the five-driving-wheel rover any significant progress up the slope. “The terrain was such that she could just not climb the slope there, even to get to where we could image around these fingers," reported Laubach. "Spirit made no appreciable progress. She was digging in instead of making upward progress.”

That attempt to climb up the northeastern slope of Home Plate would be Spirit's last. "The issue was soil-covered slopes more than 8 degrees. That's what kills us,” summed up Arvidson.

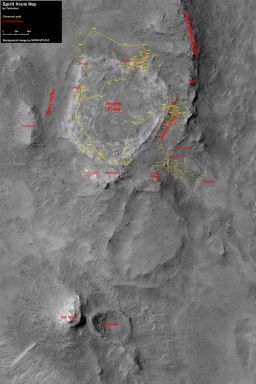

Spirit sets rove record

Spirit sets rove recordSpirit used its navigation camera to take images that have been combined into this 180-degree view of its surroundings on its Sol 1856 (Mar. 23, 2009. The center of the view is toward the west-southwest. Earlier on this sol, the rover had driven 25.82 meters (84.7 feet) west-northwestward setting a new record for a five-wheeled rover. This was Spirit's longest drive since it lost the use of its right-front wheel in March 2006. Before this month, the farthest this rover had driven in a single sol with its five wheels was 24.83 meters (81.5 feet), on Sol 1363 (Nov. 3, 2007). The rover's record-setting drive took it around the northern part of Home Plate toward the West Valley. A portion of the northwestern edge of Home Plate is prominent in the left quarter of this image, toward the south. This view is presented as a cylindrical projection with geometric seam correction.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

The MER team decided after that to send Spirit on a new route to the south. “We concluded reluctantly that we can't make it across the top of Home Plate,” said Squyres. “We just couldn’t make it around the east side. We've got to go west.”

Before the rover could change course, however, Spirit had to first safely move away from a potentially threatening little rock it had encountered. "We noticed after that last attempt on Sol 1843 that there was this rock, which looked like a potato, and it was poised to potentially fall into the right rear wheel," explained Laubach. "If that had happened, then Spirit wasn't going anywhere. With the right front wheel problem, if the right rear wheel suddenly had a 'potato' in it, Spirit would have been stuck. There wouldn't have been much hope of getting her into a position where we could get that rock out of the wheel. So we were really careful.”

Restricted sols and the weekend limited Spirit's activities from Sol 1845 through Sol 1849 (March 12 - 16, 2009), but the rover spent its work time judiciously, performing some short maneuvers on Sol 1845 (March 12, 2009) and Sol 1847 (March 14, 2009) to move itself away from the potentially dangerous 'potato' rock. "On Sol 1845 (March 12, 2009), the rover planners tried a clever trick, where they purposely forced a wheelie, then turned the wheel perpendicular, as far as possible, and brought it down to try and push this 'potato' underneath the wheel," Laubach said. "But that didn't seem to have the desired effect."

So during that weekend, on Sol 1847 (March 14, 2009), Spirit tried another tact. The idea was to have the rover turn the wheel all the way so that it could image inside the wheel, then turn the wheel back, taking an image every few degrees of turn to [effectively create] a "movie," Laubach explained. "We determined by looking at that movie that the rock was not moving," she said. "We believed then that the rock was larger than what we could see in the imaging, so we were safe to move.” Apparently, the rock was also more embedded than the engineers initially believed.

Still, the rover planners did not want to instruct Spirit to risk turning in place with the pesky potato rock near the right rear wheel. So, on Sol 1850 (March 17, 2009), they had it push forward down the slope to escape the danger. “Spirit actually did really well, even though it was pushing forward, which is not the preferred direction for this five-wheeled rover to drive,” said Laubach. “But she actually drove forward 4.79 meters (15.71 feet) down slope, and that got her away from the hazard, so we could then turn in place and drive backwards out of there.”

In between those maneuvers, on Sol 1848 (March 15, 2009), Spirit used its Pancam to check out some more light-toned soil, dubbed Edmond Hamilton, which revealed a Mini-TES silica signature like Leigh Brackett, and some light-toned nodules, nicknamed Jonathan Swift.

Spirit was slated to drive again on Sol 1852 (March 19, 2009), but with the increasing dust in the sky over Gusev Crater, and the declining power levels as a result, the rover planners decided to have the rover forego driving that sol. Instead, they had Spirit recharge its batteries. Never one to waste a Martian minute, Spirit also conducted an atmospheric argon measurement with the alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) on that sol and took some more Pancam observations and Mini-TES spectral measurements of various science targets in the vicinity.

Edmond Hamilton

Edmond HamiltonSpirit took this picture of Edmond Hamilton, another bath of light-toned soil, with its panoramic camera (Pancam) on its Sol 1848 (Mar. 15, 2009), shorting after churning it up. It showed a Mini-TES silica signature like Leigh Brackett, a batch it uncovered just a week before.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell University

One of those targets, from within Spirit's wheel tracks, the dark and aptly dubbed Edgar Allan Poe, offered up a strange, never-before-seen combination of Martian materials. Beyond what is the darkest soil this rover has uncovered to date, Poe also boasted some of the now-familiar light-toned soils and, as Bell put it, “some of the most stunning color diversity of any little patch of Martian real estate,” a description that bears repeating.

What’s actually in that haunting hollow is something the team is working on. “We're only just now able to calibrate the data and start to explore in quantitative detail all of the different color variations in this place,” Bell said today. Stay tuned.

As it turns out, having Spirit spend a sol recharging its batteries was a really good idea, not just for the sake of Edgar Allen Poe, but for what the rover was about to do. "We recharged the battery enough that we were able to dip into it a bit in order to do some long drives,” explained Laubach. And, on Sol 1854 (March 21, 2009), Spirit finally managed to split the troublesome scene at Home Plate’s northeastern edge for good, driving 13.8 meters (45.3 feet), much to the team’s delight, said Laubach.

Two sols later, on Sol 1856 (March 23, 2009), Spirit, for the first time in a long time, put her pedal to metal and blasted off, setting the distance record for five-wheel driving – 25.82 meters (84.7 feet) – and beating its own previous record by about a meter. The team, not surprisingly, cheered. Believe it or not, Spirit experienced some pretty smooth sailing on those drives. “The long drives in North Valley didn't have thick soil deposits, were fairly clear of rocks, and went slightly downhill," Arvidson pointed out.

While the going was good, Spirit kept going, completing another drive of 12.9 meters (42.3 feet) on Sol 1858 (March 25, 2009). “We felt very good about that and we're hoping to keep it up,” said Squyres.

Kit Carson

Kit CarsonSpirit took this image of Kit Carson, another trough of possible near-pure silica, with its front Front Hazcam. Today, the rover is slated to take close-up Pancam pictures, as well as position itself to use the alpha-particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS)and Microscopic Imager (MI)to confirm its composition. "It's the most exciting find of the month for sure!" said Cornell grad student Melissa Rice, who is using the panoramic camera (Pancam) now to find hydrated minerals on the surface.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

On Sol 1859 (March 26, 2009), Spirit took a break so that engineers could help the rover build the new, R9.3 flight software. “We needed to use the part of memory that the navigation software would use,” Laubach explained. “That build was successful and the navigation memory was freed up.”

Last weekend, Spirit spent some time “looking off to the northwest for possible contingency locations,” said Arvidson, “just in case we can't continue in West Valley or can't get to the south.” But on Sol 1861 (March 28, 2009) the rover drove on according to the current plan, putting approximately 22 meters on its odometer and achieving its first milestone on the western rim of Home Plate as it came to a stop at the mouth of the West Valley. We're truckin'," beamed Squyres.

As Spirit roved along, it churned up a bunch of possible silica-rich, bright soil in a considerable trough it dug, which the team christened Kit Carson. “Since Spirit's been moving, we've been taking as many Pancam observations as we can with at least the 8 of the 13 filters that I use to try and map this hydration feature, which the silica-rich materials have,” said Rice. “The problem is the downlinks have been very small for Spirit lately and we have a lot of the good data still sitting on the rover. Most of these observations, especially the ones from this month, have not been fully downlinked and calibrated,” she noted. So Kit Carson’s exact content – though she's relatively certainly it's silica-rich –is still to come.

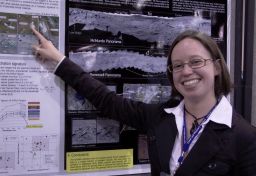

What’s really intriguing is how Rice is now regularly using the Pancam as an instrument to sleuth out compounds containing water molecules. It all started when Alian Wang, of Washington University St. Louis, was looking at the spectral signatures of the silica-rich and sulfur-rich soils Spirit has been finding, and discovered there was consistently a downturn at 1000 nanometers, Pancam's longest filter wavelength, Rice said, during an interview at the 40th annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference last week.

That finding led Wang, Rice’s adviser Jim Bell, Ed Cloutis, of the University of Winnipeg, and Rice to begin trying “to poke at this problem” to see what could be causing that, she recalled. The goal was to find a way to characterize these silica-rich materials with the Pancam instrument, so they could locate them off in the distance and identify interesting, scientifically productive places for Spirit to visit.

Melissa Rice

Melissa RiceMelissa Rice, a grad student at Cornell University, has been working with her adviser Jim Bell, the principal investigator of the panoramic cameras (Pancams) on Spirit and Opportunity, and others on pushing the limits of the stereo camera system and using it as a unique indicator of hydrated minerals. Here, she points to a poster, which she co-authored, that shows how Spirit has used the Pancam as a tool to find silica-rich materials in Gusev Crater. Rice presented the poster at the 40th annual Lunar & Planetary Science Conference held last week in The Woodlands, Texas.

Credit: The Planetary Society / A.J.S. Rayl

Cloutis, who runs a spectroscopy lab in Winnipeg, began shooting spectra of silica-rich stuff, Rice said, continuing the story. “He crushed up opals and milky quartz and silica gels from all around the world, including New Zealand, Iceland, and Canada, and he found that not all of these silica-rich, terrestrial samples had this same spectrum that the stuff on Mars has,” she said. “We knew there had to be something else that was associated with these silica-rich materials that was causing the downturn at Pancam's 1000 nanometer wavelength.”

As a grad student with “more time” on her hands than university professors or senior research scientists, Rice began looking. “We knew that silica-rich stuff had this particular spectrum, but we still didn't know what exactly about the silica would be causing this,” she said.

Using an automated script she wrote that could run through all of the spectra they had in their databases and evolve them to the Pancam wavelengths, Rice looked for candidates with the same spectral feature. “I went on a search through almost 2000 different mineral spectra to try and see what else could be causing this spectral feature and found a list of about 20 minerals that have an absorption band in the right place to give us this feature,” she said.

Those 20 minerals included hydrated magnesium sulfate, hydrated calcium sulfate, borates, carbonates, ice, and water-ice. “What all these minerals had in common is that they had H2O or OH and lots of it, so we concluded that it has to be some sort of H2O or OH that is causing this narrow absorption in the exact place where Pancam can see it,” Rice explained.

“It turns out that this feature we see is not a hydrated silica feature, but a hydration feature.” That means, basically, this Pancam method is actually more than a way to find just silica-rich stuff on Mars. “This is a hydration finder, not just a silica finder," said Rice. "This is “really stretching the limit” of the Pancam, she added. Even so, Pancam is now actually functioning as a kind of mineralogical tool. “Nobody has really used Pancam to tease out these particulars of the spectra and to try and use it for mineralogy, because there’s a suite of other instruments on the rovers that are designed for chemistry and mineralogy. But this is a great example of the beauty of a mission that lasts four years longer than expected.” Indeed.

Today, Spirit is slated to snap some Pancam images of Kit Carson and maneuver into position for observations with the APXS. Then, it will take some MI pictures. After that, “I expect more 20-meter drives,” said a confident Arvidson. “I don't think we'll have too much difficulty until we get closer to South Valley.”

Although Spirit had little choice but to go west, there is no denying that team members are concerned about this route to the south. “The thing about the western route is that it's pretty smooth sailing initially, but as we get further along, it's going to get harder,” Squyres said. “The terrain we're in now is hard-packed and gently down hill. That's good. We're going to make as much distance as we can and we'll see how it goes. But the terrain does look like it becomes less trafficable further on."

If by chance Spirit cannot make it through West Valley, what then? “We'll bop back out and look at alternate exploration sites,” Arvidson said. “There may be more silica ridges to the northwest.”

For now, however, Spirit will keep on keepin’ on to Goddard and von Braun. “The rover is now looking “right into the throat of West Valley,” as Arvidson put it. It will spend some time imaging and mapping the route south, then, he added, Then the team will try to figure out how to get by some of the little soil-covered ridges at the entrance. “That, I suspect, will be pretty easy to do, because the ridges are aligned north-south, so we don't have to climb over them, just get on the side of them."

opportunity from meridiani planum

Opportunity began the month of March on its Sol 1814 quietly, booting its new R9.3 flight software. Once that software was checked out, the rover was back on the road. On Sol 1816 (March 3, 2009), it cruised for about 40 meters (131 feet), driving backward to alleviate the still elevated motor current in the drive actuator of its right front wheel.

The MER team noticed this wheel issue last month, realizing that from Sol 1795 (February 10, 2009) through Sol 1797 (February 12, 2009) there had been a steady increase in the right front drive current draw. It was not entirely a surprise, because it had happened before.

As Jake Matijevic, chief rover engineer, noted then: "We've seen this before when we've done significant continuous driving on the vehicle going forward." And, Opportunity has been doing an incredible amount of forward driving, especially when you consider the MERs were "warrantied" for something like 600 meters (.37 of a mile) and Opportunity at that point had driven some 14,483 meters (about 9 miles).

The prescription for Opportunity's hot wheel was driving backward and taking breaks to rest. Having a robot rest "may sound silly," Squyres admitted. "But given the nature of the problem, which we think has to do with migration of lubricants [in the wheel assembly], if you let it sit for a while, the lubricants can creep back to where they're supposed to be, so resting can help the situation,” he explained.

Down on Earth, the team discussed a plan for Opportunity to really give its wheel a rest as the month progressed so they could further mitigate that elevated motor current. At the same time, the goal of Endeavour beckonsand it's still a total of 15 kilometers (9.32 miles) away by the route that has been charted, so the rover engineers experimented with some other tests to try and figure out the feasibility of multi-sol drives during the long plans over weekends.

Traditionally, on Fridays, the MER team uplinks a plan to cover the rover’s activities for the entire weekend or 3 sols. Usually, the rovers can only drive on one of those sols, because when the vehicles drive autonomously or on their own, it's a good idea that one of its ground crew check the engineering data as it comes down to Earth the next day, just to make sure the rover drove without a hitch – and, well, humans need rest too.

"Because of planning complexity and safety issues, we normally only allow one drive sol over the weekend, but because our goal is to get to Endeavour Crater as quickly as possible, we've been looking at the possibility of doing drives covering multiple sols over the weekends," Laubach recounted. "So we've been doing tests to see how we can constrain planning complexity and what kind of safety mechanisms we can put into the sequences to allow that. In one of these tests, for example, we disallowed all backward arcs.”

Endeavour's western rim

Endeavour's western rimIn the left half of this image that Opportunity took with its Pancam, you can see a western portion of the rim of Endeavour Crater on the horizon. In the right half, the rim of a smaller crater, farther away, appears faintly on the horizon. The rover snapped this picture on Sol 1821 (Mar. 8, 2009). The width of the image covers approximately one degree of the horizon. The part of the crater's rim visible here is about 16 kilometers (10 miles) from where the rover was when it took the image. It remained at that location until a drive on Sol 1823. The more-distant rim to the right, part of Iazu Crater, is about 38 kilometers (24 miles) away. Iazu, which is about 7 kms (4 miles) in diameter, is south of Endeavour.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

Because of that wrong-way drive, the MER team cancelled the planned drive on Sol 1822 (March 9, 2009) to determine the cause of the error and how to address it, Laubach said. As it turns out, it was "a very serious drive sequencing error,” she acknowledged. But it wasn’t Opportunity’s fault.

Turns out actually, the error emanated from those multi-sol feasibility studies. It was an inadvertent goof, a human error. “We forgot we had set the rover to only allow straightforward arcs, so she drove forward," Laubach explained. "While we were intending to drive backward to Resolution Crater, Opportunity ended up driving straightforward instead, because, actually, that was the only way that we allowed her to drive."

Such human errors have happened rarely on this mission, which is more remarkable than one might expect given that the rovers have gone on four and a half years longer than anyone anticipated. At the end of the sol, so to speak, no harm was done.

“We've learned our lesson from that," said Laubach. Since then, rover engineers have implemented further corrective action to guard against this type of unanticipated sequence interaction.

Blueberry fields forever

Blueberry fields foreverOpportunity took this image with its panoramic camera (Pancam) on its Sol 1825 (Mar. 12, 2009). It was subsequently rendered in false color to better show the big, "luscious" blueberries that are in and all around the fractured bedrock into which its traversed. It's been a good long while since hte rover has seen this kind of bounty of blueberries.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

Despite the glitch, Opportunity has always had the luck of the Irish and in the days leading up to St. Patrick’s Day, this rover proved again that talk of its inherent good fortune is no blarney. In fact, this lucky rover would strike pay dirt on two fronts in March.

For starters, Opportunity spotted part of the rim of Endeavour on the distant horizon with its panoramic camera (Pancam). “We're still very far away, but actually seeing it on the horizon sent chills up the spine," Squyres said.

During the ensuing sols, the rover would go on to inform the team that it had traversed into a new scene, a different landscape from what it had been roving on since leaving Victoria Crater last October.

On Sol 1823 (March 10, 2009), Opportunity resumed driving “very cautiously,” Laubach said, logging a healthy 23.47-meter (77-foot) drive. The rover drove back toward Resolution Crater, preparing to take advantage of a nearby exposed rock outcrop – dubbed Cook Islands – to conduct the second series of close-up investigations in its systematic study of bedrock and soil en route to Endeavour.

It would be an extended pit stop, serving the purpose of science, as well as resting the right-front wheel actuator and giving the engineers time to really troubleshoot the drive sequencing error.

On Sol 1824 (March 11, 2009), Opportunity completed a 4.53-meter (14.86-foot) drive to get its instrument deployment device (IDD) over a choice location on Cook Islands, said Laubach. As the rover positioned itself on the exposed rock outcrop to begin its in situ science campaign, it zeroed in on a chosen spot called Penrhyn, named for the largest and most remote atoll in the Cook Islands on Earth.

Because of its degraded, now frozen shoulder azimuth joint, positioning the IDD has become more challenging for Opportunity, but with the remarkable skill of her rover planners, it carried out the task flawlessly. “On Sol 1825 (March 12, 2009), we did a .53-meter (1.73 feet) bump to get the rover in the right position, where Penrhyn was within the reach of the IDD and she performed beautifully," confirmed Laubach. "Then on Sol 1826 (March 13, 2009), we started with the IDD campaign proper."

Opportunity began the campaign with a Mössbauer spectrometer touch, just to check things out. Then, the rover homed in on Penrhyn, taking several pictures with its a Microscopic Imager (MI) to create a mosaic.

On Sol 1829 (March 17, 2009), the rover took more MI mosaics, then placed the Mössbauer spectrometer for several sols of measurements for iron. That was, of course, St. Patrick's Day on Earth and, even though the rover wore no green, lucky Opportunity worked its IDD as if it had no issues with shoulder whatsoever. Once the MI pictures were beamed down to Earth and the scientists were able to get a good, close-up look, they were stoked by what they saw.

“Somewhere in the last kilometer, we crossed over a boundary and into something different,” said Squyres. “The MI images show that we've got big, juicy blueberries in the bedrock and we haven't seen that in a thousand sols.”

Things only got better. Following more testing of a workaround on the ground with the Surface System Test Bed (SSTB) rover at JPL’s indoor Mars Yard to compensate for the loss of the Z-encoder on its rock abrasion tool (RAT), which failed last January, the team felt confident that Opportunity was ready to once again use the instrument.

A good RAT

A good RATOpportunity took this picture with its Microscopic Imager (MI) after it successfully brushed and grinded into the bedrock it's been investigating for the last couple of weeks. It was the first time the rover had used its rock abrasion tool (RAT) since its Z-encoder failed in January 2009.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

The rover moved in on Penrhyn on Sol 1832 (March 20, 2009). Then, using the new workaround, Opportunity guided its RAT and successfully performed a seek-scan to locate the rock surface. The following sol, it conducted the first part of a brushing activity on Penrhyn. That same sol, 1833 (March 21, 2009), it used its MI to document the brushing. "It was our first successful RAT brush since the Z-encoder failed and it was a big success,” Laubach reported.

Opportunity then pulled out its iron-detecting Mössbauer spectrometer and placed it on the brushed target, conducting a couple of sols of integration or observations. The rover switched IDD instruments on Sol 1836 (March 24, 2009), putting its alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) down on the brushed target to measure the elemental composition.

The following sol, Opportunity conducted another RAT seek-scan to set up for a grind on Penrhyn, slated for the next sol. With the rover planners solidly behind it, Opportunity was unstoppable. On Sol 1838 (March 26, 2009), the rover completed its first successful RAT grind since the Z-encoder failed. “We're thrilled about the results of both the brush and the grind,” said Laubach.

Opportunity spent last weekend taking more MI pictures of the polygonal cracks that are bursting with big blueberries and also conducted some more Mössbauer observations on the RAT grind area on Penrhyn, Laubach said.

Now, as March gives way to April, Opportunity remains positioned at the Cook Islands outcrop, continuing its in situ science campaign with the robotic arm (IDD), wasting no valuable time as it rests it weary right front wheel. No fooling.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth