Casey Dreier • Feb 08, 2016

What Does a 'Good' Budget for Planetary Science Look Like?

One of the first things I will look for after tomorrow’s release of the 2017 budget proposal for NASA will be the budget for the Planetary Science Division. This part of NASA supports all robotic exploration of the solar system (and is the single source of research funding for planetary scientists).

Many of you know the story. Starting in 2013—and occurring every year thereafter—the White House proposed significant cuts to planetary science. The Planetary Society and our members fought these cuts year after year. Each year Congress rejected most or all of these cuts, fortunately, and we’ve seen the White House get closer to our recommended level of $1.5 billion per year for a healthy, balanced planetary program at NASA.

In that sense, a planetary budget of at least $1.5 billion in the 2017 request would be “good.” But that’s not the only metric. Even though we’ve likely passed the worst of the planetary budget crisis, the program needs to rebuild. There is the Mars 2020 mission, the Europa Multiple-flyby mission with a possible lander, and new small- and medium-class missions all planned to launch in the early 2020s. The next five years must be spent building these missions, and I’ll be looking for this to be accounted for within the five-year budget projections included in the President’s Budget Request.

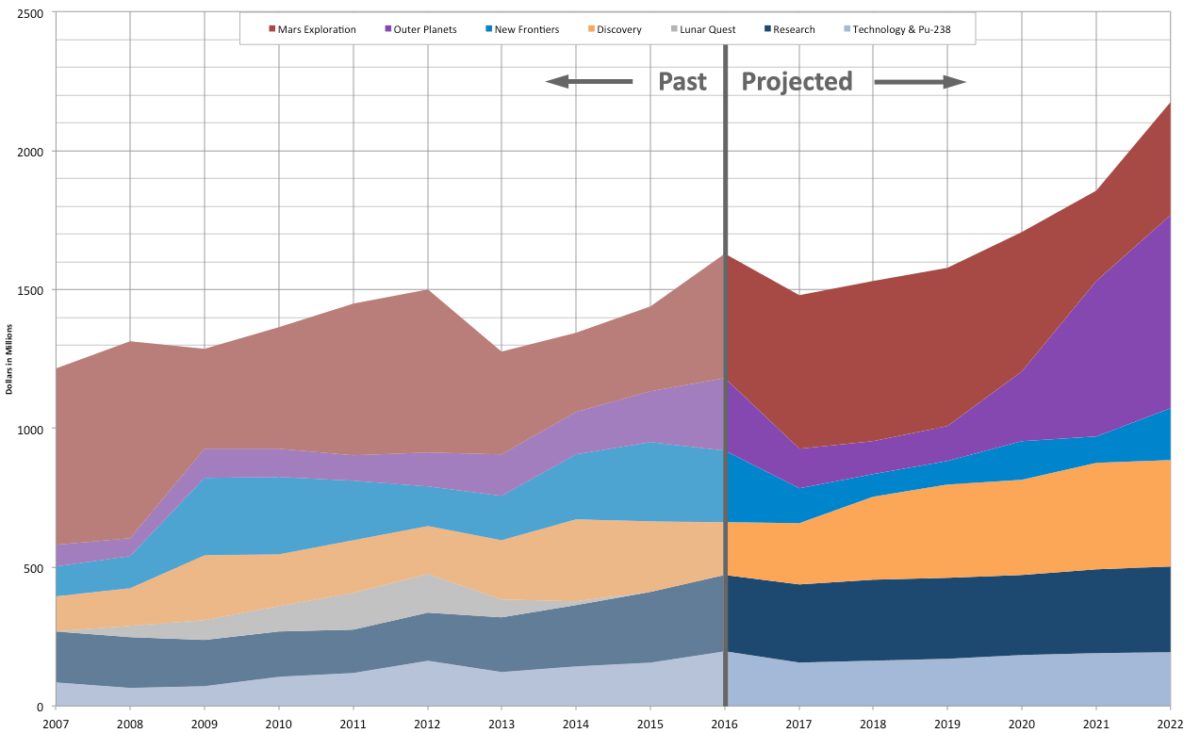

But what would a good five-year projection look like? My colleague, Jason Callahan, took a stab at this and put together the following budget projection based on public data from last year’s budget request.

This projection assumes:

A 2023 launch date for a $2B Europa multiple-flyby mission with an additional $750M lander on a launch vehicle that costs roughly the same as an Atlas V.

The next New Frontiers (medium-class) planetary mission stays on track for launch no later than 2025.

The next Discovery (small-class) mission launches in 2020.

The follow-on Discovery mission is selected by the end of 2019 for launch in 2023.

A Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter-class ($700M) tele-orbiter launches to Mars in 2024.

Research and technology funding grow with inflation.

Mars Opportunity is funded through its current extended mission.

Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter is funded through its current extended mission.

I should strongly emphasize that we used highly idealized cost development curves and best-case development timelines and funding practices. But this does give us a rough sense of where the budget needs to go: to $2 billion by the end of the decade. It also shows us that anything less than $1.48 billion in 2017 would likely be disruptive to the program.

We will update this article once we see the President’s budget request on Tuesday.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth