A.J.S. Rayl • Feb 28, 2011

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Efforts to Recover Spirit Expand as Opportunity Wraps Up Work at Santa Maria

The Mars Exploration Rover (MER) mission emerged from its third solar conjunction this month and, as March roars in, is embarking on its 86th month on the Red Planet. While Opportunity roved away from a surface target it had been studying at Santa Maria Crater and on to an intriguing blue boulder, JPL engineers on Earth stepped up their efforts to recover Spirit, which has been silent, ostensibly in hibernation mode, since late March, nearly one year ago.

Solar conjunction – an approximate two-week period when the Sun is directly in between the Earth and Mars – occurs every 26 months and disrupts communications between the two planets. As a result, Earth-to-Mars communication moratoriums are imposed for all spacecraft at Mars. By mid-February, solar conjunction had passed, the moratoriums were lifted, and the MER team got back to the business of exploration.

Only the sounds of static silence emanated from Gusev Crater this month, but it isn't over for Spirit until it's over, as retired New York Yankee catcher and modern philosopher Yogi Berra might put it. Although this rover's last electronic communiqué was received on its Sol 2210 (March 22, 2010), the MER team's attempts to recover their charge has picked up in earnest.

"We've emerged from solar conjunction and are continuing the search for Spirit," confirmed JPL's John Callas, MER project manager. "We have the Deep Space Network (DSN) listening and we are also continuing with our sweep-and-beep activity. However we've made changes to that. We've shortened the commands so we get more of them in and also have a greater the probability of Spirit getting them. We are also covering more frequencies to count for any possible changes that may have occurred in the tuning of the rover's receiver, and we're covering more time in the day in case the clock has drifted."

Simulation of Spirit at Troy

Simulation of Spirit at TroyThis artistic image -- in which Astro0 [Glen Nagle] of UnmannedSpaceflight.com has placed a two-dimensional MER into a scene created by pictures taken by Spirit -- illustrates the rover's current location in Gusev Crater, known as Troy. Although the angles are admittedly a little off and the disturbed soil isn't quite right, it offers the reader a glimpse into the scene on Mars.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / ©Astro0 2009

In just a couple of weeks, mid-March, it will be the period of maximum solar insolation, the time of the Martian year between spring and summer where the Sun is at its highest in the sky and the rovers can produce the most energy. With no beep from Gusev Crater yet, there is now a mix of feelings and concern about Spirit.

"We know that the peak of the solar insolation is coming up and we know that we are right now at the time of highest probability of hearing from the rover," said Callas. "Everyone's a grown-up here, and so we are all recognizing the realities of the situation. But it's difficult to say how people are reacting."

"It's very business like, and we're just continuing to look at how best to listen and get signals out," said the team's stoic Swede, Ray Arvidson, deputy principal investigator for rover science, of Washington University St. Louis.

After more than seven years – and for many team members who go back to the rover's births, more than a decade – the prospect of losing Spirit is personal. "There is still cautious optimism absolutely," offered Scott Maxwell, rover driver team lead. "In my personal individual case, I would call it enthusiastic optimism." Although not everyone is as enthusiastic or perhaps as attached to the rovers as Maxwell, overall hope still floats for Spirit's recovery.

Technically, there's no off-switch on the rovers. Even so, once this peak energy time passes next month, if Spirit has not responded, "the chance of the rover surviving another winter and responding next summer is very unlikely," said Callas. "But there are more things we're going to try, including sending [new] commands to the rover."

As February turns to March, all fingers are crossed. There are wishes, hopes, even prayers being launched from cities, towns, and villages all across Earth that Spirit phones home soon.

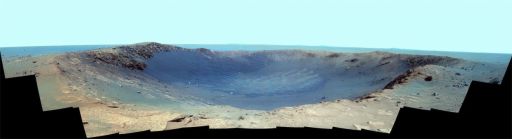

Santa Maria in false color

Santa Maria in false colorOpportunity spent its seventh anniversary of its landing on Mars investigating a crater called Santa Maria, which has a diameter about the length of a football field. This scene looks eastward across the crater. Portions of the rim of the much larger crater, Endurance, appear on the horizon. The panorama spans 125 compass degrees, from north-northwest on the left to south-southwest on the right. It has been assembled from multiple frames taken by the panoramic camera (Pancam) on Opportunity during the 2,453rd and 2,454th Martian days, or sols, of the rover's work on Mars (Dec. 18 and 19, 2010). The view is presented in false color to emphasize differences among materials in the rocks and the soils. It combines images taken through three different Pancam filters admitting light with wavelengths centered at 753 nanometers (near infrared), 535 nanometers (green) and 432 nanometers (violet). Seams have been eliminated from the sky portion of the mosaic to better simulate the vista a person standing on Mars would see.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

Over on the other side of the planet, at Meridiani Planum, Opportunity emerged from solar conjunction in fine form. The rover promptly returned a healthy amount of data on Luis de Torres, a surface target named for one of Christopher Columbus' crewmembers on the first voyage of his Santa Maria. The rover's Luis de Torres is located along the wall of the southeast rim, on the edge of what may be a shallow secondary impact depression the team calls Yuma.

The team chose this area for Opportunity to hunker down and work during the two-week solar conjunction period, because it was a safe location, and because it is in the area where the signature for hydrated sulfate, a mineral that indicates past water, was detected from orbit by the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM), the visible-infrared spectrometer onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO).

During solar conjunction, Opportunity checked Luis de Torres out thoroughly, brushing off the surface contamination and dust, and taking pictures and measurements with instruments on its instrument deployment device (IDD) or robotic arm. Once conjunction was over, the rover ground into the surface target with its rock abrasion tool (RAT) and took more pictures and observations.

Opportunity RATs Luis de Torres

Opportunity RATs Luis de TorresThis picture shows a shadow of Opportunity just after the rover used its RAT to grind into the surface target dubbed Luis de Torres. The target names around Santa Maria honor the men that Christopher Columbus brought together for the first voyage of the Santa Maria in 1492. De Torres served as interpreter for the multilingual crew.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

"We can say that the natural surface has a lot of contamination on it and that the interior [ground down] surface is a purer sulfate, but there's more detective work to be done to determine why this area turned up the hydrated sulfate signature from orbit," offered Arvidson, who is a co-investigator on CRISM.

Since data was still coming down as of late last week, the science team has not rendered any hypotheses as to why CRISM detected the signature for hydrated sulfate over this area. But the scientists do have, Arvidson said, "a lot of ideas." At the moment, however, those ideas are not ready for prime time publication.

Last week, Opportunity roved northeast from Luis de Torres, driving counter-clockwise around Santa Maria Crater to Ruiz Garcia, a slate-blue colored boulder that it has since been examining. This rock was also named after one of Columbus' crewmembers from the Santa Maria's first voyage, and the rover is now finishing up its check-out of this interesting, equant rock. From Ruiz Garcia, the plans calls for Opportunity to drive another 20 to 30 meters further to the northeast to a chosen waypoint, where it will take some final stereo images of the interior of the crater. The scientists hope to combine all the stereo images the rover took here and create a 3-D map of Santa Maria. "Then we'll start heading for the hills," said Arvidson.

Ruiz Garcia

Ruiz GarciaOpportunity took this picture of Ruiz Garcia with her Pancam on approach to the boulder last week. Stuart Atkinson added the near true color to bring it to "life."The rock appears "kind of bluish," said Ray Arvidson. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / color by S. Atkinson

Although the winds of the late Martian spring are kicking up dust and causing extremely dusty, almost opaque skies over the Opportunity's site, it's what usually happens this time of year, and so the team is not worried.

"The atmospheric opacity has been moving up and down because of the season," confirmed Arvidson. And even though Opportunity's power levels have dropped, the rover, he added, "still has an abundance of power to do what we need to do."

Although there are no compelling targets between Santa Maria and the 22-kilometer (13.70-mile) diameter Endeavour Crater from what can be seen in the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) pictures taken from MRO's orbit, Opportunity, in addition to necessary rest stops, will be making at least a couple of stops en route to take samples of the bedrock and soils.

If something interesting or odd or different should be found on the way to Endeavour, the team will instruct Opportunity stop and take a look. "We're a discovery led mission," reminded Callas. "We'll drive for Endeavour and if we see compelling science along the way we'll stop, of course, but really the plan is to get where we need to go. So, once we're done at Santa Maria, it will be time to get back up on the Interstate and put the pedal to the metal."

Spirit from Gusev Crater

As Earth and Mars orbited on and the period of solar conjunction passed this month, JPL and NASA engineers began increasing and expanding efforts on February 18th to recover Spirit. They are listening more often via the DSN every day on the X-band, direct-to-Earth frequency, and, on the possibility that its mission clock faulted and the rover does not know what time it is, they are also continuing to page Spirit, using the sweep-and-beep technique where they send command signals in attempts to nudge the rover to respond in the case she's waiting to hear from Earth.

The DSN X-band frequency reference offset has been stepped over a much larger range to account for the possibility of a degraded receiver on the rover. DSN searches have also been modified to occur over different local times of day on Mars covering the possibility that the rover's clock has drifted significantly since March of 2010.

Spirit at Troy

Spirit at TroySpirit almost disappears into the landscape in this simulated image of her on the shoulder of Home Plate, an eroded over, circular volcanic plateau. This artist's rendition shows the rover's position where she became mired in Martian sand at Troy. The panorama was taken Spirit on her Sol 743, as she descended from Husband Hill toward Home Plate. UnmannedSpaceflight.com's Astro0 [Glen Nagle] inserted the rover into the scene at Home Plate, which here occupies the center of the image; the rover is in the valley to its right.Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell / Glen Nagle

The duration of the sweep-and-beep command, meanwhile, has been shortened from 20 minutes to 10 minutes, increasing the number of command attempts that can be made, and increasing the chances for those commands to be received by the rover within her 20-minute awake (fault) window.

"Shortening up the sweep-and-beep command time to only about 10 minutes long greatly increases the probability that if the rover is listening that the command gets in," confirmed Callas. "The rover is programmed to only listen for 20 minutes every hour it is awake and if it hears nothing it shuts down and goes back to sleep. Now it will take 10 minutes instead of 20 minutes to get the [commands] in, so this way there is more likelihood of actually getting the command in. The analogy I make is that it's the difference between trying to drop a tennis ball into a tennis ball can, where it just fits, versus dropping a ping-pong ball into a tennis can. So there's a much higher likelihood of getting it in the hole."

Another advantage, Callas said, is that they can send more commands, effectively doubling the number of commands to the rover. "We are peppering the sky, if you will, with the sweep-and-beep signals," he said.

70-meter dish at Goldstone

70-meter dish at GoldstoneFront view of the 70-meter dish, also known as DSS-14, at the Deep Space Communications Complex at Goldstone, California. Located in the Mojave Desert, Goldstone is part of NASA's Deep Space Network (DSN), which provides radio communications for all of NASA's interplanetary spacecraft and is also utilized for radio astronomy.Credit: NASA / JPL

The other significant change the Spirit recovery team has made is that they are now sending those sweep-and-beep command signals out over more frequencies. "We have predictions based on what we think the rover's frequency should be, but if its receiver has been degraded from the cold of winter, it may have lost its tuning. So we're covering more frequency bands to make sure that if the rover is there and listening, it should hear us," he explained.

"The other thing we've been doing is recovering a greater portion of the time of day on Mars, so we're not just reaching out when we think the rover would be awake listening," Callas continued. "We're concerned that if the clock on the rover has drifted significantly during the last 11 months the rover's timing could be off, so we've expanded our window each day we are listening and reaching out to the rover to cover for that possibility."

In the mix, the JPL engineers have been consulting with the engineers and designers from the companies that built the receiver and the clock to see if they can offer any insight on how these devices might deteriorate when they're stressed. It could be, for example, that the brutal Martian cold may have affected the crystal oscillator fixed to the rover's low gain antenna [LGA] thus changing the predicted frequencies on which Spirit would be listening. It could be that the rover is listening but on a different range of frequencies than the team has been using.

"We've been using all the information and ideas coming from those vendors," said Callas. "While many of these are worst-case estimates of how much something might have changed, these are things we need to account for, to make sure that we're covering all the bases and turning over every rock, to ensure that we're giving Spirit every opportunity and every possible chance to respond."

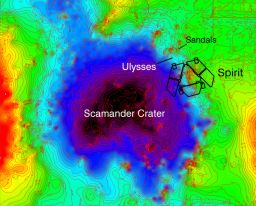

Topographic map of Spirit's location

Topographic map of Spirit's locationThis topographic map of Spirit's location at Troy represents low elevations in black, purple, and blue and high elevations in red. It was developed based upon Spirit's camera images of the location, taken before it got mired at Troy. The topographic model has had a regional slope removed, which reveals that Spirit's left wheels are sitting inside a subtle depression that the team has named Scamander crater. The right-side wheels are outside the depression.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Ohio State University

Since no communication has been received from Spirit since Sol 2210 (March 22, 2010), there is growing concern that the rover may not be phoning home ever again. The period of maximum solar insolation (energy production) for Spirit occurs around mid-March 2011. "We are likely in a regime where probably more than one thing has gone wrong on the rover," Callas acknowledged. "We have enough paths of redundant communication of the rover that because we haven't heard from Spirit yet, there have to be at least two things wrong, not just one, and we're now going to explore these possibilities."

In addition, the engineers are considering sending other more aggressive commands to the rover, because perhaps Spirit is hearing the signals from Earth, but can't respond for whatever reason, because of more than one failure. "We're going to be sending commands to the rover to try and change the configuration on the vehicle to account for some of these possibilities," Callas said. "But it's a complex thing. When you send commands to change the state of the rover, you don't know if the commands got in and changed the state, so anything you do after that, you have to consider now two possibilities – either they got in or didn't."

In another Callas analogy, it would not be unlike driving out of your garage and down the street and wondering if you forgot to close the garage door. You push your clicker, but then wonder if it actually worked and closed the garage door, so you push it one more time. "Then, it's: 'Oh but maybe it did close it, and maybe I just opened it again, and I'll push the clicker one more time. And then it's: 'Did I just close it or open it?' So you're left with this uncertainty because you don't have confirmation on what you've done and if it's changed things in that way," he explained.

Despite the new efforts in earnest however, Callas did note that "the time is probably approaching when things are probably starting to become unlikely," as he put it. "The thinking is: if Spirit survived the winter, the vital components should have survived. But if she didn't survive the winter, then all bets are off. It would be unusual for the rover to have lost both the transmitter on the X band system and the UHF system, but otherwise bein functional health," he pointed out. "We are moving into this regime of lower probability scenarios."

Spirit still shining at Troy

Spirit still shining at TroyIn this picture of Home Plate, taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, you can easily see the stark white figure that is Spirit to the left (west) of the geologic formation in this image enhanced by rover poet Stuart Atkinson. "It's just a screengrab from the excellent HiRISE IAS Viewer," he said. "I added some colour, then highlighted the position of Spirit. If you look carefully you can actually see bright trailing leading to Spirit - this is the result of the (right front) broken wheel being dragged through the dirt, unearthing brighter material beneath." Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / enhancement by S. Atkinson

There is no off switch on the MERs; therefore, if Spirit has survived and is alive, she is waiting for the crew and, noted Callas, will try to communicate each day until she dies. "However, if we don't hear from Spirit in the upcoming weeks, the probability of her coming back at sometime in the future is unlikely."

That would mean the mission curtains will fall on Spirit and she will rest, ostensibly in peace, where she is, a memorial to one of the most legendary missions of all time. But it the curtains haven't dropped and it isn't over yet, and the MER team is still projecting optimism.

Maxwell, for one, is choosing to remain positive. "You remember back to when Spirit landed, she bounced around the surface and she got in touch with us a little after we expected to hear from her," he pointed out. "And I expect she's enough of a drama queen that she's going to do the same thing here and wait until the very last day we could possibly expect to hear from her. Then, the next day is when she'll contact us. She's like that. She's that kind of a girl." T here's also the possibility that Spirit might have been trying to make contact this whole time or that she's been listening on a different frequency, he continued. "I do think she's there and I think we're going to hear from her. Right now my hat is off to the team that's working really hard on recovery of Spirit and I can't wait until they turn the keys over to me and the other rover drivers to finish getting her out of Troy. Personally, I remain confident we are going to hear from Spirit." That noted, he added: "I've got my fingers crossed that I turn out to be right about this."

A good omen ?

A good omen ?This image, which Spirit took with its Pancam just about one year ago, features a discreet sign of luck that many MER team members and MER followers hope is still good omen of things to come for this beloved rover. Enlarge the image, then look inside the circular depression. As rover aficiando Stuart Atkinson,who discovered this, put it: "That has to be a lucky horseshoe in that hole." Actually the rover created the circular depression with its rock abrasion tool (RAT); nevertheless, the horseshoe certainly wasn't planned. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / colorization by S. Atkinson

In any case, the team is not ready to give up. "We are looking at exhausting these possible, multiple faults scenarios with some additional [configuration changing] commanding over the next several weeks," said Callas. "I'm speculating on a time, because we haven't laid out the exact timeline, but probably we will continue these increased efforts through the March and into April," he said.

"Longer term, we will probably continue with the sweep-and-beep activity, but will probably go from seven times a week, as we are now, to maybe just one or two times a week," Callas continued. "Further, we did program onto the rover before she went to sleep, back in March 2010, one UHF pass per week for the rest of calendar 2011. So we will probably continue to ask the relay orbiters to listen to that one pass a week for the rest of 2011." That means the team will be listeing and reaching out, at least a low level – once a week sweep and beep and once a week UHF – for the rest of the calendar year.

"We all want Spirit back – but – and I'll be saying this a lot," Callas added, "we are doing what we said we were going to do, which is to wear these rovers out, to leave behind no unused capability on the surface of Mars and we're doing that. That means there will come a day for both rovers where we have worn them out and that's it, so we have to just you know face up to that reality, because it's going to happen."

If Spirit isn't recovered, those on the team, and those who have followed and care about these Martian robot field geologist explorers will take the loss in his and her own way. he parting for most though will be far more than sweet sorrow, and more like the death of a close friend – "a friend," as MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres described it years ago, "who lived a long and admirable life."

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

Opportunity began the month of February working a light work schedule during solar conjunction, carrying out a series of preprogrammed science tasks while parked on the southeast rim of Santa Maria Crater.

Positioned right on the edge of Yuma, what may be a shallow, secondary impact crater along the crater's rim wall, the rover spent most of its time during the two-week conjunction period studying a surface target there called Luis de Torres, after a member of the crew Columbus set sail with in 1492 on the first voyage of his Santa Maria, one of the trio of ships he launched from Spain in search of the New World.

Contrary to popular myth, Columbus's crew on the first voyage was not comprised of just criminals and heathens, but "mostly 'hometown boys' from Andalusia, and nearly all experienced seamen," according to Keith Pickering, a computer systems consultant and historian living in Watertown, Minnesota. Pickering has been researching Columbus' voyages since 1991, and claims authorship on two papers on the explorer's navigation that have appeared in scholarly journals. Luis de Torres, turns out, was the interpreter for Columbus' multi-lingual crew aboard his Santa Maria, and, interestingly, a converted Jew.

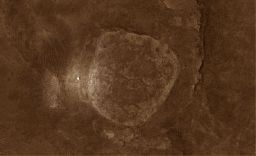

Santa Maria Crater

Santa Maria CraterThis HiRISE image shows Santa Maria Crater, Opportunity's last planned science stop for the rest of the long journey to Endeavour Crater. The tiny yellow dots roughly approximates the size of the rover at different positions at the impact site.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech /UA / labeled by Stuart Atkinson

"This spot [on the edge of Yuma] was selected because it was safe to do a groundtruth of what we think we're seeing in CRISM, which is a hydrate of sulfate with one water in the lattice," said Arvidson. CRISM, of course, is the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). Arvidson is a co-investigator on CRISM. Its detection of hydrated sulfate in this location was the first such detection made at Mars by a multi-spectral imager.

Opportunity took full advantage of the solar conjunction lull to thoroughly check out Luis de Torres. "First looked at the undisturbed surface with the microscopic imager (MI) and the alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS), then we brushed it and repeated that," said Arvidson. "And for the brushed surface, we left the Mössbauer spectrometer down at night, integrating overnight."

Since the Mössbauer's power source has degraded to such an extent that a good, solid reading that required four hours at the beginning of the mission now requires more than 40 hours, and the light work schedule during conjunction enabled Opportunity to collect a lot of spectra in those overnight integrations.

Despite the communication moratorium on all signals and commands sent from Earth, spacecraft at Mars can send electronic communiqués to their ground teams and usually check in a couple of times during the solar conjunction periods. On its Sol 2496 (January 31, 2011) Opportunity returned engineering telemetry that indicated all was well and that she was sporting 524 watt-hours under extremely dusty skies. Although the atmospheric opacity or Tau was elevated to1.07, the rover's solar panel dust factor showed that she was still utilizing more than 60% of the sunlight 'fuel' she was taking in.

When Opportunity checked in again on Sol 2499 (February 3, 2011), she was producing 585 watt-hours of energy even though the skies were still extremely dusty and the Tau was still up around 1.0. That bump in power may well mean that some of the wind gusts kicking dust into the atmosphere also blew off some of the accumulated dust on her solar panels. Since this is the time of year when the winds blow and dust devils skirt across the landscape of Mars, the rover's power levels fluctuate up and down routinely, as does the opacity in the atmosphere.

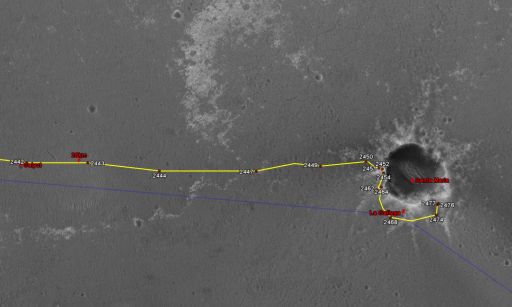

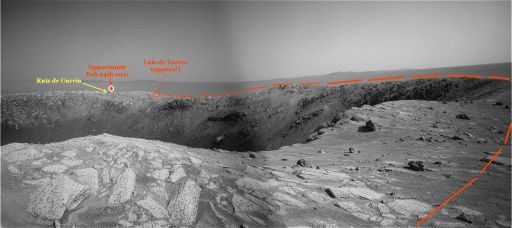

Opportunity's work sites at Santa Maria

Opportunity's work sites at Santa MariaOpportunity took this Pancam image of Santa Maria last December, and Stuart Atkinson, of UnmannedSpaceflight.com took the initiative of labeling it to show where the rover has been working this month. For more pictures, poetry, and musings of Opportunity's journey to Endeavour, check out his blog at: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / add-ons by S. Atkinson

As the second week of the month began, on Sol 2504 (February 8, 2011), Opportunity took a single APXS atmospheric argon measurement, part of a mission-long investigation of the Martian atmosphere, then continued her study of Luis de Torres.

Six sols later, the rover emerged from the solar conjunction, spending her Sol 2510 (February 14, 2011, Valentine's Day) in recovery, as the ground crew at JPL reviewed her physical status. The rover's telemetry showed that she was in fine condition. With the known exception of the miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES), all the orver's systems were healthy and her Mössbauer spectra from Luis de Torres were all good. The following sol, 2511 (February 15, 2011), she reported that her power levels were back down to around 505 watt-hours, while the Tau remained elevated at 0.94, while her solar array dust factor was 0.597.

On Sol 2512 (February 16, 2011), Opportunity got back to a full schedule and resumed normal tactical operations. The rover set up her RAT and, on Sol 2513, dug into Luis de Torres. "We ground in about 3-millimeters (0.12 inch), then did MIs, and on Sol 2515 (February 19, 2011), put the APXS down on the RAT hole for three sols worth of integration," said Arvidson. "We integrated for a long time in order to get really good signal-to-noise data so that we can back out the abundance of light elements. Since we can't detect carbon and hydrogen directly, we needed a long integration to identify all the other cations, like magnesium, iron, and oxygen. Then we'll apportion the oxygen to the cations we can detect, and the excess oxygen is going to be associated with hydrogen and carbon," he explained.

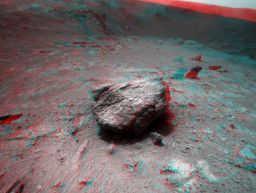

Luis de Torres

Luis de TorresOpportunity took this picture of Luis de Torres with the Pancam on its Sol 2513 (Feb. 17, 2011), after grinding into the spot with its rock abrasion tool (RAT). The rover completed the Rating after emerging from solar conjunction three sols earlier. The Pancam team at Cornell rendered it in false color.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

What have the scientists learned about Luis de Torres?

"We know that the RATed surface is a purer sulfate than the natural surface, which has a lot of contamination on it," said Arvidson. "But it's still too early to interpret the results because we just got the latest data down from the APXS," he added.

Asked if there was any further idea why this signature was detected by CRISM at Santa Maria, he said he has "all sorts of ideas." But, he added, "we're not ready to talk about it because it hasn't been vetted through the science team yet."

The analysis of Luis de Torres is a difficult one because the only mineral detectors Opportunity has right now are the Mössbauer spectrometer and the multispectral mode of Pancam, Arvidson reminded, and these are only applicable if the target is iron bearing. "Fundamentally the problem is we don't have a working Mini-TES. That is the instrument that would complement CRISM's ability to detect water in minerals, and without it we have to do a lot of detective work to figure out what we're seeing."

In addition, Arvidson noted, "the CRISM detection of the monohydrated sulfate on the southeast rim of Santa Maria was a tough job because there weren't that many pixels to cover that small patch." With MRO being in an extended mission, however, the CRISM team has had the time and flexibility to conduct oversampling of various areas within the rover's landscape, a technique that allows for a better 'read' on what's down below.

"Normally when we acquire the normal FRT or full resolution target data, those pixels are spaced cheek-to-jowl, right up one another. But since CRISM's optics are on a gimbal, as MRO flies over, the optics can be rotated to track the surface and we can get 6-meter samples between centers of the pixel by overlapping the imaging, rather than just the standard 18-meter pixel samples," Arvidson said.

Santa Maria pan

Santa Maria panOpportunity took the images that went into this, her most recent panorama. Stuart Atkinson, of UnmannedSpaceflight.com, did us the favor of putting it together and adding color.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / assembled and colorization by S. Atkinson

"You can't change the size of the pixel projected on the surface, but you can oversample in the along-track direction," Arvidson added. "It's done all the time on Earth with thermal radiometers, so it's nothing spectacularly new."

Michael Malin of Malin Space Science Systems, in fact, oversampled many regions on Mars with the Mars Orbital Camera (MOC), onboard the Mars Global Surveyor (MGS). "But this is the first time it's been done with a hyper-spectral imager, so the breakthrough here is the application with CRISM where we rotate the optics so that we keep the instrument looking close to the same spot in order to get overlapping pixels of the same area, and the [resulting] ability to pick out minor details we couldn't before," Arvidson explains.

Since CRISM detected the hydrated sulfate at Santa Maria last year, the instrument's team has used CRISM to oversample Victoria Crater, and, lo and behold, detected the same hydrated sulfate signature in areas where Opportunity had been during its study of the crater from September 2006 to October 2008. "We hadn't seen this signature before over Victoria with CRISM, because we never had an oversampled observation where we were taking 6-meter samples alongtrack with 18-meter pixels," Arvidson said. "Now we have detected this signature in two places Opportunity has been," he confirmed -- Victoria Crater [after the fact] and Santa Maria [before the rover's arrival there in December 2010].

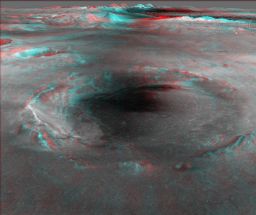

Ruiz Garcia in 3-D

Ruiz Garcia in 3-DOpportunity took this picture of Ruiz Garcia with its Pancam just this past weekend, which with blue-red glasses appears in three dimensions. The boulder lies along the southeast rim of Santa Maria Crater. It's rugged and ragged and even sports a few of the famous Martian "blueberries" in its mix. Named for one of the crewmembers on the first voyage of Christopher Columbus' Santa Maria back in 1492, it is the last rock the rover is scheduled to study up close in this area. In coming sols, Opportunity will be taking off for the highly-anticipated next destination, Endeavour Crater, now just 6.5 kilometers (about 4 miles) away. Stuart Atkinson rendered it in 3-D. For more of Atkinson's work check out his blog at: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com Credit: NASA /JPL / Cornell / 3-D by S. Atkinson

And there's more. Arvidson said CRISM has also detected the same hydrated sulfate signature in a fresh, 2.2 kilometer-diameter crater, dubbed Ada, some 100 kilometers (62.13 miles) to the southeast. "And we see it in the northern part of Meridiani in the valley, so the detection is there. It's real," he underscored.

Those signature findings are evidence that the past water that flowed there was regional. "The question now is whether we'll have enough data of the right type from Opportunity to make a self-consistent model." Stay tuned, there's sure to be more.

With the in-situ investigation at Luis de Torres complete, Opportunity began driving northeast, or further counter-clockwise around Santa Maria, making a 7.4 meter (24-foot) move to the northeast along the rim, on Sol 2518 (February 22, 2011).

On the following sol, it drove another 15.3 meters (50 foot) toward its next rock target, a boulder the team nicknamed Ruiz Garcia. The hematite-rich "blueberries" are all around the boulder and even appear to be coming out of it. Although "blueberries" aren't exactly blue, the color of this rock appears to be a derivation of slate blue and the hue may well be as a result, at least in part, of the little round spherules. Named after another one of Columbus' crew members, Ruiz Garcia is "an equant rock, and so it seems to be very resistant and represents, probably, a different kind of rock than Luis de Torres," said Arvidson. The rover took some close-up images of this rock with her MI and then got to investigating its composition with the APXS.

Endeavour in 3-D

Endeavour in 3-DGet your blue/red glasses and check out this 3-D picture of Endeavour Crater, Opportunity's next big attraction. By combining two different views of Endeavour Crater rendered by Google Mars, Stuart Atkinson was able to create a 3-D view of the crater. The view is vertically stretched 3x (times) to bring out detail in the crater rim. "I love this view," he says. "It really shows very clearly the uneven nature of Endeavour's floor, and how those eastern, crater-spattered hills dominate the whole crater."

Credit: Google Mars / S. Atkinson

From Ruiz Garcia, Opportunity will continue north for another 20 to 30 meters to her final imaging waypoint. There, she will take another series of wide baseline stereo images of the crater interior with her panoramic camera (Pancam). The plan is that with all the stereo Pancam imaging the rover has taken from various points around the crater rim, the scientists will be able to produce a really high quality 3-D map of Santa Maria, the youngest, freshest crater Opportunity has studied during her mission.

"Once that's done, we'll be heading for the hills," said Arvidson.

As February gives way to March, the rover's power levels have dropped down into the low 400s. The Tau remains elevated, up around 1.00, and the rover's solar array dust factor is registering 0.624. The MER team is not concerned.

"It is that time of year and we expect and see these fluctuations as the spring and summer winds kick up the dust," Arvidson shrugged. "We're fine with power and have plenty of energy to do what we need to do, which is to get on with driving to Endeavour."

It can't happen soon enough for the rover drivers. Endeavour is now just 6.5 kilometers (4 miles) away, and Opportunity could be back on the road late this week.

"Obviously, we recognize that we need to give Santa Maria the most thorough treatment we can with the time we have, and do right by the science," noted Maxwell. "But we are right in the middle of the prime driving season, so this is the time to really make tracks for Endeavour, and I can't wait to get back on the road."

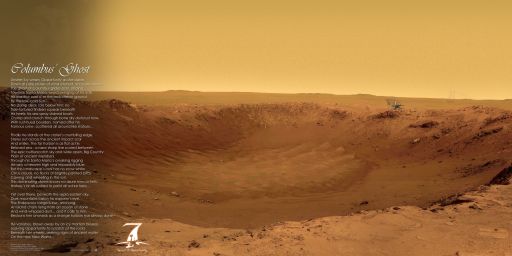

Columbus' Ghost

Columbus' GhostEnjoy the other "poemster" from MER poet Stuart Atkinson, and art designer Glen Nagle (aka Asto0), put together this month. To get wallpaper and higher resolution downloads, please go to: http://astro0.wordpress.com/mer7/Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / Maas Digital / words by Stuart Atkinson, poster design by Glen Nagle / Columbus by John Vanderlyn

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth