A.J.S. Rayl • Feb 28, 2010

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Spirit Parks for Winter, Opportunity Tastes Chocolate Hills

As winter put the freeze on in the southern hemisphere of the Red Planet, the Mars Exploration Rovers slowed down a bit, but continued throughout February to demonstrate the mettle that made them famous: Spirit successfully drove backwards, parked in place for the season, then continued working, as Opportunity roved through rock debris on a cruise around the rim of Concepción Crater.

Despite being redesignated a “stationary research platform” at a NASA press conference last month and then being written off as dead in an obituary in the scientific journal Nature, Spirit proved this month it is still very much ‘alive’ and capable of roving.

The reports of Spirit’s death are “greatly exaggerated,” Steve Squyres, principal investigator for rover science, noted in his response to the Nature article, adapting the famous comment made by Mark Twain more than a century ago when he was prematurely declared deceased. Then the team and the rover moved on.

Spirit spent the early part of February maneuvering itself with backward drives from within its embedded position at Troy, where it is still straddling the edge of the shallow, sand-filled Scamander Crater. The prime objective was to reposition itself in order to angle its solar arrays to catch the most direct rays from the Sun in the northern sky.

From November to early January, Spirit had attempted to drive forward, but wound up basically spinning its wheels, sinking further into the sulfate-rich sand in which it has been embedded since last April, and getting nowhere. But when the rover started driving backwards last month, using a kind of breast stroke motion with its wheels, it began making progress. In the process, the rover did manage to improve its tilt a bit this month, but wasn’t able to alter its position as much as the team had hoped. A counterclockwise yawing or side-to-side movement during its last drives prevented it from moving into the desired position and by mid-month power had dropped below the level the rover needs for turning its wheels.

Spirit had no choice but to park, its arrays positioned at about 9 degrees to the south, and prepare for the brutal temperatures of the season. The progress the rover did make though was enough to get the entire MER team smiling again.

“The last 10 drives we did before we stopped on Sol 2169 (February 8, 2010) actually achieved 34 centimeters (13.38 inches) of progress,” noted Ray Arvidson, the deputy principal investigator, of Washington University St. Louis. That may not sound like much, yet it was enough to change what had long been a bleak outlook. “I think we solved the extrication problem,” he said, adding that if the rover had a little more energy and time, it might well have “popped out” of its predicament.

During its final drives this month, Spirit succeeded in moving quite a bit of the powdery sand away from its wheels, and it moved away from the pointed rock under its belly, known as Belly Rock, so that it is no longer a threat.

A good omen?

A good omen?This image, which Spirit took with its Pancam this month, features a discreet sign of luck that just may be a harbinger of things to come for this determined rover. Click to enlarge, then look inside the circular depression. As rover aficiando Stuart Atkinson, who discovered this, put it: "That has to be a lucky horseshoe in that hole." Actually, the rover created the depression with its rock abrasion tool (RAT), but the horseshoe wasn't planned. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / colorization by S. Atkinson

The prospects for a future of freedom, however, are on hold until the Martian spring. “Spirit has parked her wheels for the winter,” said John Callas, MER Project Manager, of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the rover’s birthplace and mission control site.

Spirit’s power levels are currently below what was once thought to be fatal levels as far as operations go. “It could be worse,” pointed out Jake Matijevic, chief rover engineer, “and it probably will get worse in the next couple of months.”

For now, though, Spirit is continuing to work, taking pictures with its panoramic camera (Pancam) and its navigation cameras of the soils in front of it and around it, and snapping some more images of its underbelly with its microscopic imager (MI).

The rover won’t even try to turn wheels again until perhaps August or September when the Martian spring 'blooms' in the southern hemisphere of the planet. Then, said Arvidson, even though it's got a science campaign laid out, Spirit will probably first start driving again, since it's "almost out” of its sandy snare. With only four fully functioning wheels, three on the left and one on the right in the middle, “a lot of it will be very difficult,” he admitted. “We're going to have to do a lot of turning about the right hand side, so we're not going to drive far. But we're not necessarily a static lander.”

Meanwhile, the engineers at JPL have already been assessing the drive capabilities with the rover replicate in the In-Situ Instrument Laboratory (ISIL), according to JPL’s Scott Lever, an MER mission manager. “We did some 4-wheel drive testing in the ISIL and did well, surprisingly well,” he said.

First, Spirit has to get through its fourth Martian winter. The prognosis for its survival is good right now. But, given the rover’s current the unfavorable tilt , the MER team expects that it will go into a hibernation mode, “much like a bear in a cave,” as Callas has said, or like C3PO in episode 3 of Star Wars. Spirit will shut down and snooze.

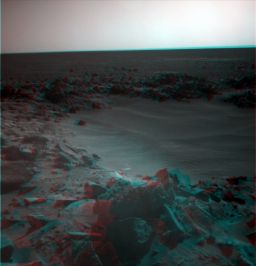

Parked for winter

Parked for winterSpirit recorded this fisheye view with its rear hazard-avoidance camera after completing a drive on its Sol 2169 (Feb. 8, 2010). The drive left the rover in the position where it will stay parked during the upcoming Mars southern-hemisphere winter.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

“Of course we don't know for certain, but our modeling strongly predicts that Spirit will trip the low-power fault and go into a hibernation mode sometime within the next four to eight weeks,” elaborated Sharon Laubach, the MER integrated sequencing team chief at JPL.

When, and if, that happens, Spirit won’t have enough power to wake up and regularly check in with its crew on Earth, although it may occasionallywake up and phone home. The team will keep an ear out, listening with Deep Space Network and with Mars Odyssey throughout the Martian winter. We’ve set up a regular listening schedule, so if she wakes up, then we'll be there to hear it,” said Callas. It could be that Spirit will hibernate for several months though and not communicate at all during that time. "There are always uncertainties in estimates and projections, and there is always risk,” he underscored.

At this point, the team is cautiously optimistic that come spring Spirit will wake up and be raring to rove out of the sand trap and launch into the planned science campaign, detailed in the December and January MER Updates. “We're making all the plans as though that is going to be the case,” said Matijevic.

“We do think Spirit can survive the winter and when she wakes up on the other side we fully expect to attempt extrication again," said Laubach. "But it all depends on the vagaries of the environment of Mars.”

In essence, it’s up to Mars now, like Squyres has said in challenging times past. The team is preparing for all the eventualities over which it may have control, and no one is betting against this little rover-that-could and has so many times.

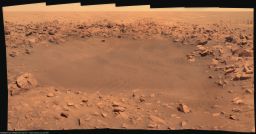

Concepción Crater

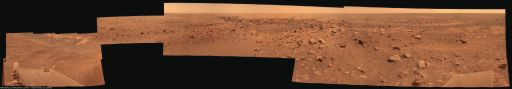

Concepción CraterOpportunity took the images that went into this picture of Concepción Crater with its Pancam this month (Feb. 2010). Using the raw imagery put onto the web at JPL and Exploratorium, MER artist James Canvin produced this picture in the living color you see here. "Notice the very faint hills on the horizon about 1/4 in from the right edge - that is Bopolu Crater more than 50 kilometers away!" he points out.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / rendered by James Canvin

On the other side of the planet at Meridiani Planum, Opportunity has been checking out the rim of Concepción Crater, the youngest crater the rover has encountered in its six-plus years of exploring Meridiani Planum. With rocks lying all about its rim, this crater is, as Squyres described it, “a real rubble pile.”

The rovers’ rocker-bogie suspension system gives them real stability in negotiating such rocky Martian terrains. Even so, Opportunity is carefully maneuvering its way around the rocky site. “These rovers can drive over rocks, but we're very cautious,” said Lever.

To protect its belly, the rover planners (RPs) and the rovers alike have been taught to avoid going over anything higher than 10 centimeters. And, when a plan calls for using the instrument deployment device (IDD) or robotic arm, for example, the team reminds the rover to stay on stable ground. “The IDD will work fine and the rover will sit on a rock fine and there's no danger at all,” Lever said. “The danger is that if the rover catches a rock on the edge or the rock is unstable and the IDD is placed within millimeters of the ground or anything happened, then the rocker bogie system would shift very quickly and all of the sudden the IDD would move very quickly and the instruments could be damaged. So we don't do IDD work with the rover on a rock and at Concepción we're just being careful to not get into areas where that could happen," he explained. The reason the team doesn't use the rovers to their full capacity is simple, he said. "We want to keep them around a long time.”

As Opportunity has moved in and examined this fresh young crater, science team members have been debating its age and working to refine estimates. The rovers do not have crater-dating instruments onboard; therefore there is no way of knowing exactly how old the crater is. But at this stage the “guesstimate,” according to crater expert and MER science team member Matt Golombek at JPL, is that Concepción is “thousands to tens of thousands of years old, definitely younger than 100,000 years old.”

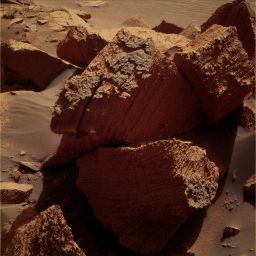

Chocolate Hills

Chocolate HillsOpportunity took this image of the Chocolate Hills rock that it studied up-close this month (February 2010) with its panoramic camera. It was enhanced by Stuart Atkinson, whose work has been appearing in these Updates frequently.Check out Atkinson's "Road to Endeavour" blog at http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / enhanced by S. Atkinson

Oppotunity spent a couple of weeks this month taking time to stop and taste Chocolate Hills, a rock with an intriguing dark rind that may be what is called impact melt, an indication this rock was once molten.

While the scientists analyze the data it sent home this month, Opportunity has roved on. “We're roving clockwise around Concepción, looking at other targets,” reported Lever, “shooting with remote sensing and seeing if there's anything the scientists want to put the IDD down on.”

Since Opportunity is closer to the equator than its twin, it has basically coasted through its first three Martian winters. This time around, however, its power levels are being impacted enough that the team has scheduled sols “here and there,” Laubach said, for the rover to focus on re-charging its batteries.

“Although the drives will get shorter as we get close to the Martian winter solstice, we should be able to continue driving Opportunity through the winter,” added Callas.

Now, as February turns to March, Opportunity is checking out the rocks in one of the more dominant rays of debris emanating from the center of the crater and which were created by whatever impacted the ground. The rover will spend some more time in coming sols looking at those ejecta and other rocks on the ground before moving out and onward to Endeavour Crater, its next big attraction, still at least a year's worth of drives away, if all goes well.

Not in a store near you ...

Not in a store near you ...... but we wish it was. For years, there has only been the Mars bar, a confectionary delight that was just reintroduced to the U.S. market last month. Some enterprising candy company might be wise to consider a competititor and why not a Chocolate Hills bar? Are you reading this Cadbury? Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / art by Stuart Atkinson

“We're going to pay special attention to the ejecta at Concepción by taking a lot of ground shots,” Lever said. “If the scientists see a ‘dinosaur bone,’ they'll stop and look at it. And, I have a feeling the rover is going to find some more juicy targets around this crater before we take off for Endeavour.”

February 2010 has been an eventful month and the MER team members have every reason to feel good, especially with Spirit’s progress. “We know what we're doing as a team,” summed up Arvidson. “And morale is," he added, "incredibly high.”

In other MER news, the rover team has submitted its proposal for a seventh mission extension, which is now in the hands of a review board. That review board will make its recommendations, probably sometime in the next couple of weeks and then NASA will make a decision on what happens next.

The Sounds of Roving

Spirit and Opportunity do not carry microphones, but they do have accelerometers, scientific instruments that measure all the small bumps and vibrations the rovers experience while moving and which are typically used to determine the position of the rover on Mars. Throughout the last six Earth years though, the ever-creative and thoughtful engineers at JPL have been taking those recorded vibrations of the rovers driving across rocky terrains, plains, mountains, and craters of Mars and converted them to WAV files, the format that compact discs use, and then finally to mp3, a patented digital audio encoding format.

Simulation of Spirit in the Columbia Hills

Simulation of Spirit in the Columbia HillsTo create this image, a computer simulation of Spirit was dropped into a Navcam panorama captured on Spirit's sol 438, as it was climbing into the Columbia Hills. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech; Rover model by Dan Maas; synthetic image by Koji Kuramura, Zareh Gorjian, Mike Stetson and Eric M. De Jong

Since these vibrations are extremely low frequency, much lower than humans can hear, the engineers sped them up about 1000 times, much like playing a tape in fast-forward on an old tape recorder. The end result? Audio files we can hear. And now NASA and JPL have posted those files. Listen to this 30-second excerpt of Spirit from its hiking days at Husband Hill in 2005 and this Opportunity excerpt from drives of the rover's current location at Concepción Crater.

The full-length audio file for Spirit, which is about 30 minutes, covers a time period from Sol 1 to Sol 2164 (January 4, 2004 to February 3, 2010), while the Opportunity file, about 60 minutes in length, covers Sol 1 to Sol 2143 (January 24, 2004 to February 2, 2010) Interestingly, you can actually hear that the trek across Gusev has been a bumpy ride for Spirit, while Opportunity, which has mostly been cruising the flat plains of Meridiani Planum dotted with craters and rippled dune fields and comparatively few rocks, has had a much smoother ride. To access the complete versions of these unique Martian recordings go to: http//marsrover.nasa.gov/spotlight/20100222a.html

Spirit from Gusev Crater

Just days after being declared a stationary research platform in a NASA press teleconference on January 26, Spirit was roving onward, seemingly trying to show its worth and working its hardest to reposition itself along the edge of the shallow sand-filled crater called Scamander. The rover has been embedded in this spot, located in a general area dubbed Troy on the west side of Home Plate, since last April. And it was in fact making progress.

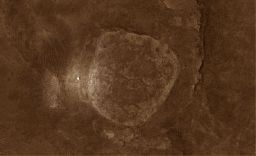

Spirit still 'alive' and roving

Spirit still 'alive' and rovingIn this picture of Home Plate, taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, you can easily see the stark white figure that is Spirit to the left (west) of the geologic formation in this image enhanced by Stuart Atkinson. "It's just a screengrab from the excellent HiRISE IAS Viewer," he said. "I added some colour, then highlighted the position of Spirit." For more of Atkinson's enhanced images and poems, particularly of targets being investigated by Opportunity, check out his blog, called "Road to Endeavour" at: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / enhancement by Stuart Atkinson

On Sol 2161 (January 31, 2010), Spirit, though only producing about 188 watt-hours, turned its wheels backwards, using several autonomous recovery techniques to prevent its drives from terminating early because of mobility faults caused by soil resistance. When the effort was over, the rover had backed out another several centimeters.

The best news was that Spirit didn’t sink any further into the sulfate-rich sand and it managed to improve its tilt by about one degree. Not a lot, granted, but every degree translates into about 5 additional watt-hours of power.

As February dawned at Gusev, the plan was for Spirit to continue driving backwards for as long as its energy would allow.

Mars seemed to be cooperating offering fairly clear skies. The rover measured tau, the amount of dust in the atmosphere, at 0.359, and its dust factor, the amount of dust on its solar arrays, at 0.523, meaning it was still utilizing more than half the sunlight hitting its solar arrays for power production.

During the first several sols of the month, Spirit mostly conserved its energy for the next drive, but did take some pictures of the soils beneath and around its wheels. Then, on Sol 2165 (February 4, 2010), it followed commands and turned its wheels. As it did, it yawed, or moved side to side; consequently it made less progress, gaining only a miniscule improvement in tilt.

With its energy levels continuing to decrease, the MER team began “winterizing” the rover, as Arvidson put it, in preparation for the long, brutally cold season ahead even as it planned the last drive attempt before having to hunker down. The objective for the last drive was for Spirit to flatten its suspension system on the right side thereby lifting or accentuating the suspension wheelie on the left side, with the ultimate goal being to level out the arrays and improve its northerly tilt to catch more sunlight.

On Sol 2169 (February 8, 2010), Spirit revved up and went for it. Unfortunately, the rover was unable to pull it off. Energetically, it was just tuckered out. So, with 7,730.50 meters (4.80 miles) on its odometer, the rover parked for the winter. “That was her last drive until spring,” Callas confirmed for the Update.

Simulation of Spirit's predicament

Simulation of Spirit's predicamentThis artistic image – in which Astro0 has placed a two-dimensional MER into a scene created by pictures taken by the real rover – illustrates Spirit's predicament at the location in Gusev Crater known as Troy. Although the angles are admittedly a little off and the disturbed soil isn't quite right, it offers the casual reader a glimpse into the present scene on Mars – and this rover scribe thinks it's a pretty cool illustration.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / ©Astro0 2009

By all appearances in the images sent home, however, Spirit did succeed in backing out enough to move quite a bit of soil out from around the wheels and to put some real estate behind, err in front of it.

Why after so much struggling in the sands of Ulysses did Spirit suddenly seem to make tracks?

“When we did the calculations, the amount of pressure exerted by the soil deposits and rocks around the wheels exceeded the thrust that was available with the 5-wheel drive and then the 4-wheel drive, so we were basically spinning in place, as you know,” Arvidson said. “We needed to do something that would reduce the local soil pressure around the wheels and it turned out this wheel wiggle did that.”

During the backward drives, Spirit performed wheel wiggles – essentially moving the wheels side-to-side – along with turning its wheels, a technique the engineers call the "breast stroke." As the rover employed the breast stroke technique, it cleared out much of sand from around its wheels, lowering the soil pressure locally so the rover could effectively back up.

“Those wiggles seem to have solved the problem of what's called the rolling resistance, the resistance due to the soil surrounding the wheels and just making the wheels spin in place,” Arvidson said. “The wheels couldn’t go forward because there was so much pressure resisting them. Wiggling creates the space and lowers the pressure and that's why I think we got the 34 centimeters (13.38 inches) in the last 10 drives. We were wiggling as part and parcel of that activity.” The last couple of drives, he added, were shorter, due to declining power, the reason Spirit made less progress than it did during the earlier backwards drives.

“Basically, once we stopped trying to go forward and started going backwards she was driving several centimeters a pop,” summed up Laubach.

The progress made also apparently eliminated the threat of Belly Rock, the pointed rock that had been touching Spirit’s underside. “We think Belly Rock is now out from under the rover,” Laubach said.

While there are no certainties or guarantees on Mars anymore than there are on Earth, from the looks of things now, Spirit has a good chance of leaving naysayers in the dust once the Martian spring pushes the Sun higher in the sky, provided of course that the beyond-freezing temperatures don’t cause something on the rover critical to roving to break. “Even as a 4-wheeled rover, she was doing several centimeters a drive and if she keeps that up, it's very likely she'll get out,” Laubach said, agreeing with Arvidson.

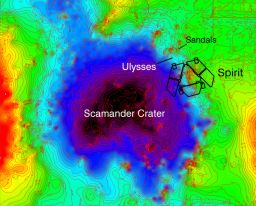

Topographic map of Spirit's location

Topographic map of Spirit's locationThis topographic map of Spirit's location at Troy represents low elevations in black, purple, and blue and high elevations in red. It was developed based upon Spirit's camera images of the location, taken before it got mired at Troy. The topographic model has had a regional slope removed, which reveals that Spirit's left wheels are sitting inside a subtle depression that the team has named Scamander crater. The right-side wheels are outside the depression.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Ohio State University

Still, winter for Spirit, especially if it trips the fault, will be a nail-biter for all concerned. For the previous three Martian winters, the rover managed to climb onto north-facing slopes so that its solar arrays could bask in the warmest rays of the Sun. Last year, it actually angled its solar arrays 30 degrees to south by hanging off the northern edge of Home Plate, the circular volcanic formation that has been a primary area of study for the rover. Now, with its arrays pointed at 9.25 degrees south, this will be without doubt the toughest winter for Spirit and, arguably, its toughest challenge to date.

As February progressed, the MER team continued with the winterizing process, commanding Spirit to adjust its communication window for the optimal times of the sols during the coldest part of the season. The engineers developed a special table of long-range UHF communication passes with Mars Odyssey to cover winter and beyond. “We are uploading schedules to the rover so it will know when to communicate with Earth or with the orbiting Mars Odyssey during the rest of this year and into 2011,” Callas said. “The rover will use these schedules whenever it has adequate power to wake up.”

Meanwhile, Spirit continued working. It snapped a set of "before" pictures of its surroundings from its winter parking spot. On Sol 2174 (February 13, 2010), Spirit positioned its IDD to the most favorable orientation for winter, then used it navigation cameras and panoramic camera (Pancam) to document the terrain and itself. These images will be used to compare with pictures it will take in spring so that scientists can study the effects of the Martian wind.

The rover also took some more pictures toward the south to aid preparations for possible future drives, although, with only four of its six wheels still working, the rover is not expected to move any great distances. Theoretically, especially given the progress made in its recent backward drives, the rover could move meters, “even tens of meters,” suggested Arvidson.

By mid-month, Spirit’s power levels had dropped further. As of Sol 2176 (February 15, 2010), it was producing 173 watt-hours of power, a level once considered “fatal” as far as operations are concerned. When power levels decrease, the rover’s wake times get shorter; consequently, the engineers began deleting many of the energy-consuming communication passes just as they had done in winters past.

Taking it backwards

Taking it backwardsThis two-frame animation, is created from two wide-angle pictures that Spirit took this month shown one after the other. The rover took the images with its rear hazard-avoidance camera: one at the end of the previous drive two sols earlier and then after the Sol 2147 (Jan. 16, 2010) drive. Visible changes from the first to the second, as a result of the rover's motion, include the landscape appearing to shift to the right and the forground rocks near the bottom of the image appearing to come closer. The view is to the south, looking at and beyond Spirit's rear wheels, with the bottom surface of a solar panel at the top of the image. During this drive, Spirit moved about 3.5 centimeters (1.4 inches) southward and yawed slightly counterclockwise. Neither the right-rear wheel (at the left in this view) nor the right-front wheel can contribute to driving.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

Although its energy continued to decline pretty rapidly, the tau remained fairly steady, around 0.361, and so, too, the dust factor at 0.526. Since winter is generally a fairly calm time on Mars this was not surprising, but it was in any case much welcomed.

Spirit managed to work through the month, focusing on emptying its onboard flash memory as much as possible, sending home all essential science and engineering data and continuing with imaging. “We’re finishing off a color mosaic of the newly exposed sulfate soils in Ulysses, because we kicked up these waves of soil with the LF wheel driving backwards,” said Arvidson. “We'll get a couple more Pancam color images and will continue to monitor the dust in the atmosphere.”

But things are “moving pretty quickly” to the point where Spirit will be able to only wake-up, check in, and monitor the tau. “Soon we'll wake up, take the tau, and then go back to bed or wake up, communicate, and then go back to bed and that's expected to happen in maybe three, four weeks,” said Arvidson.

Once Spirit’s power levels drop to around 155-160 watt-hours, the engineers anticipate the rover will trip a low-power fault and shut down all systems except its master clock and the charger for the batteries, effectively going into hibernation, as Callas informed in the January MER Update. At that point, all the energy it takes in from the solar arrays will go to its two main batteries and to the master clock.

“According to our current projections, Spirit could go into this hibernation mode as early as March and as late as April,” Laubach said.

When and if that happens, it is possible Spirit will wake up now and again to check in, and then go back to sleep. “That would be a good thing because there’s data and information in those communications and it would give us status reports on the rover,” Callas noted. But it is also possible that Spirit may not wake up at all until the spring Sun rises, sometime in August or September, said Arvidson, when it can collect enough sunlight energy to come back online regularly.

Meanwhile, the “winterizing” preparations continue for both the rover and the team. “We’re parking the Pancam mast assembly (PMA) and the high gain antenna (HGA) at angles to minimize any shadowing on the solar arrays,” Laubach said. “We always have to think of these things, even though the likelihood is low, but just in case, for example, the actuator on the PMA fails at that azimuth, then we want to be looking at what we want to look at.”

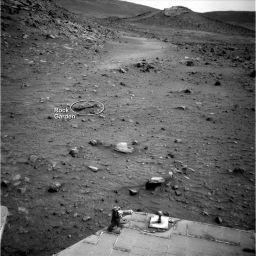

Scene of the slip

Scene of the slipThe cluster of rocks labeled Rock Garden in this image is where Spirit became embedded in April 2009. The rover used its navigation camera to capture this view of the terrain toward the southeast from the location it reached on its Sol 1870 (April 7, 2009). The ground just left of the center of the image is where Spirit became embedded in April 2009. Wheels on the western side of the rover broke through the dark, crusty surface into bright, loose, sulfate-rich sand that was not visible as the rover approached the site. Turns out the rover had been snared by the edge of a shallow Martian sand-filled crater, now known as Scamander Crater.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

As for the MER crew, the team’s leaders are preparing for the worst of possible outcomes, just in case. Since the MERs have been going and going and going beyond all dreams and expectations, Callas scheduled an ‘all-hands’ meeting at JPL to discuss the engineering realities and to make sure everyone on the team is fully aware of just how tough this winter is going to be for Spirit. The long period of silence, as well as the possibility, though seemingly unlikely at this juncture, that it may stay silent could send team members into a kind of rovershock.

Laubach, who suffered the silence of the Mars Polar Lander back in 1999, has also been talking with her drivers and engineers one on one, bracing for all possibilities.

Projections from last month were that Spirit should not suffer a master clock fault when it goes into hibernation and, according to Callas, that still holds. “The master clock fault is like when the power goes off and your alarm clock doesn't go off to wake up and you have to rely on the Sun streaming through your window to wake you up,” he explained. “It looks like we'll avoid that. But there is uncertainty in our estimates and atmospheric and environmental conditions could be worse than we're expecting, so there's still a risk."

If the projections are off and Spirit does trip a master clock fault, the rover could sleep for an untold number of months, “like Sleeping Beauty,” said Callas. That would leave the engineers to figure out when to try and wake-up the rover and hope that the rover is listening when they try. A Martian day or sol is about 39 minutes longer than an Earth day and if the clock faults, knowing just when to make contact with Spirit could be a confounding proposition until mission control and rover synch up.

Still, survival is what’s most important and right now the odds are in Spirit’s favor. “I think she'll meander through the varieties of low-power fault and succeed in getting through winter over the course of the next several months,” said Matijevic.

The progress Spirit made this month with the backwards drives it was able to do before it ran out of photon power clearly lifted the spirits of team members. There is every reason now to hope that Spirit will be able to leave its sandy snare and rove on.

“We're not going to drive far,” Arvidson said. “We've got things to do where we are. We are in a really rich target environment. The new material we've exposed in Ulysses and Scamander Crater is something we want to look at. We've also exposed part of the Rock Garden, which as we thought are a bunch of rock clasts that have been jostled about by the underbelly. So when we wake up and start off again, we'll probably want to do some characterization of the newly exposed material,” he said.

Although Spirit did take some drive pictures to the south this past week, no one on the team is expecting the rover to make it what had been its next desitnations, a mound and house-size pit named for rocket pioneers Robert Goddard and Wernher von Braun. "We've kind of given up going to von Braun and Goddard, but we can drive some meters, maybe tens of meters to other targets in the area,” Arvidson added. “We know what we can do and we're going to do it.”

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

After completing its final approach to the young, 10-meter (33-foot) diameter crater called Concepción in late January, Opportunity began the month of February carefully snapping more pictures of the rocky site, reminiscent of the Viking 2 lander site at Utopia Planitia.

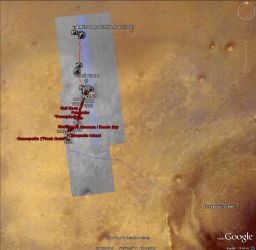

Opportunity's route to Concepción Crater

Opportunity's route to Concepción CraterAn ilustration like this obviously doesn't just come from one camera or one person. In fact, it takes a 'Martian village' to make it happen. Hopefully, we are giving all credit where it is due here. Credit: Google / basemap by ESA / DLR / FU Berlin Gerhard Neukum / NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / Add-ons: additional background layer, based on HiRISE image(s) covering the area outside map provided by Google Earth, by S.F.J.Cody / route map layer, including labeled ground features, starting at Victoria Crater by Eduardo Tesheiner; planned route layer starting at Concepción, based on a paper by Tim Parker posted at Unmanned Spaceflight.com, also by Tesheiner.

Producing some 300 watt-hours of power, Opportunity was almost bounding with energy compared to its twin over at Gusev, but with the Martian winter just setting in, that luxurious likely wouldn’t be maintained. Just two sols later, on Sol 2144 (February 3, 2010), its solar array energy production had dropped to 270 watt-hours under hazy skies, a tau of 0.415. The rover had a dust factor of 0.470, so it was making use of about 47% of the sunlight hitting its solar arrays.

During the first week of the month, Opportunity began its clockwise tour around the crater with a 9-meter (30-foot) drive, taking pictures as it went. The team had spotted some intriguing looking ejecta or rocks that also appeared to be suitable for further in-situ investigation and the rover headed that way. On Sol 2145 (February 4, 2010), the rover made a 10-meter (33-foot) approach to a rock target dubbed Chocolate Hills.

It was the dark rind or crust on Chocolate Hills that lured the team. That rind could be impact melt, a sign that the energy released by the impact or whatever made the crater caused the rock to become temporarily molten.

Impact melts often include small particles, called impact melt spherules, that splash out of the impact crater, as well as larger sheets of melt that coalesce in low areas within the crater. While comprised predominantly of the rocks at the location, impact melt can contain a small, but measurable amount of the impactor, so the reason the MER scientists wanted to have the rover take the time to stop and 'taste' Chocolate Hills is obvious.

Concepción Crater

Concepción CraterConcepción Crater is the youngest or freshest impact crater that Opportunity has examined up-close. The MER scientists now estimate it to be between 1000 and 100,000 years old. In this picture, you can clearly see ejecta [rocks] lying on top of the rippled terrain, some forming what are known as crater rays. "Most dramatic of all is the horizon with many peaks forming the rims of Endeavour, Izau and if you look very closely, about 1/3 in from the right you can see Bopolu Crater," notes James Canvin, who generated this picture using the raw imagery put onto the web.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / rendered by James Canvin

Two sols later, on Sol 2147 (February 6, 2010), Opportunity completed a 2-meter (7-foot) short approach to move in on Chocolate Hills and two sols after that it performed a small turn-in-place to maneuver close enough to put the instruments on its IDD down on the rock. Since the rover broke its shoulder actuator last year, it has been handicapped with a 4-degree-of-freedom azimuth limitation and so must fine-tune its positioning for close-up studies.

On Sol 2150 (February 9, 2010), Opportunity began its in situ investigation by taking a series of pictures of Chocolate Hills’ dark rind with its microscopic imager (MI). Then it placed its alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) on a specific target called Aloya to begin determining the composition of the rind. It followed up with another set of MI pictures on Sol 2151 (February 10, 2010), and then placed its Mössbauer spectrometer on the target.

The next sol, Opportunity made a small turn to reposition its IDD to check out another spot on the surface of the Chocolate Hills. On Sol 2154 (Valentine’s Day 2010), the rover used its MI camera to take a series of pictures of a lighter colored rind that the team labeled Arogo. Then it kissed the spot with its APXS. On Sol 2157 (February 17, 2010), the rover repeated these two sets of measurements on another target dubbed Tears.

Chocolate Hills

Chocolate HillsOpportunity took this image of the Chocolate Hills rock with its panoramic camera (Pancam) on Sol 2144 (Feb. 3, 2010), using several of the camera's filters, at wavelengths of 750 nanometers, 530 nanometers, and 430 nanometers. This image of the crusted rock perched on the rim of the 10-meter (33-foot) wide Concepción Crater is rendered here in false-color to increase the contrast between different rock and soil types on the Martian surface.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell University

Opportunity finished its studies of the Chocolate Hills on Sols 2159 and 2160 February 19-20, 2010), then moved to its left on Sol 2161 (February 21, 2010) to resume the its clockwise cruise around Concepción, roving toward the “most obvious ray” of impact debris or ejecta that streaks away from the crater, according to Scott Lever.

“An interesting point is that if you look at the crater in the recent HiRISE images from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), you can see the dust rays spiting out in a radial direction and there are some very strange dark rays,” noted Lever. “It turns out that some of the chunks of rock are so big that when this HiRISE image was taken, the Sun was at an angle that was off to the side and not high above and the shadows of these big rocks created this dark look. In the image, it looks like it's got all these really cool dark rocks, but it was really just a bunch of light material with shadows.”

Opportunity drove again on Sol 2163 (February 23, 2010), and took another short 8-meter jaunt on Sol 2165 (February 25, 2010). “The Sol 2165 drive had to be very short in duration because we were squeezed by a late uplink pass and a very early MRO pass – we used MRO on this particular sol instead of Odyssey,” explained Lever. “The squeeze was so tight we could only get about approximately 15 minutes of duration for the drive sequence. That's very short. Our goal was about 10 meters and I think we got more than 8 meters.”

In any case, Opportunity is now in the ray and the team is loving it. “We’re seeing some truly spectacular rocks,” said Lever. Some of these spectacular rocks look like shatter cones, rare distinctively conical-shaped rock fragments that feature striations radiating from the apex and are only known to form in the bedrock by the high pressure of meteorite impacts. But, according to Matt Golombek, the scientists have not yet identified any of these rocks as shatter cones. “So far we are just seeing angular blocks of ejecta,” he told the Update.

Although Opportunity’s power levels bounced back up to around 300 watt-hours, the end of month leaves the rover sporting about 278 watt-hours. “The power levels are getting a little bit low,” said Laubach. “We haven’t really had any winter troubles with Opportunity before. But this winter that we've been having to start scheduling re-charge sols.”

Opportunity did rest its right front wheel – which has for the last year been drawing higher than normal currents from time to time – during its study of Chocolate Hills this month. And in all its drive those currents were “well-behaved,” as the engineers put it. Nevertheless, the team continues to have the rover conduct mitigation techniques. “We are doing regular full side heating – right side, left side heating if we can,” said Lever. So far, knock on Martin rock, it’s all good.

Throughout February, the rover continued to regularly open the elevation mirror on the miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES) in hopes a Martian wind will blow by and clear the dust out of the instrument. So far, no improvement has been observed yet, but there is little wind this time of year, so, as the saying goes, nothing ventured nothing gained.

In the coming sols of March, Opportunity will continue its trek around and about the rim Concepción Crater. “We may change direction at times to avoid debris,” Lever pointed out, “but basically we're going around clockwise and that will continue.”

Once Opportunity's work at Concepción is complete, it will drive onward toward Endeavour.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth