Emily Lakdawalla • Jan 18, 2008

MESSENGER's First Mercury Flyby Highly Successful

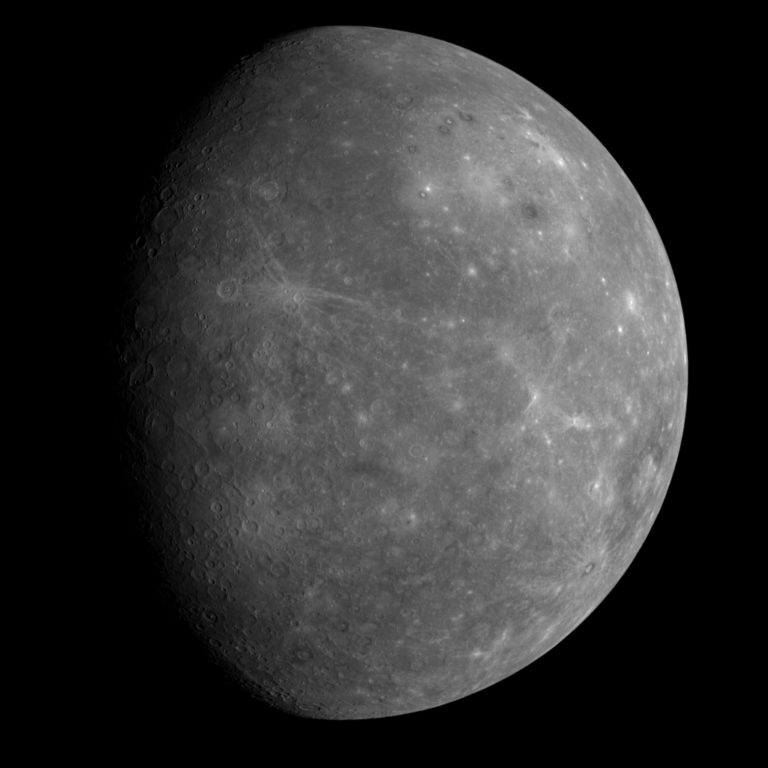

On the evening of Tuesday, January 15, the MESSENGER science team crowded around a computer screen, anxiously awaiting their first view of the previously unseen hemisphere of Mercury. The moment was more dramatic than initially expected, because the MESSENGER mission had had a planned Tuesday morning deep-space communications session taken from it to respond to an emergency on another mission. To make sure that at least one image would be returned from the spacecraft before another day passed, the MESSENGER imaging team was asked to select one, and only one, photo to be given highest priority and returned from the spacecraft ahead of other instrument data. They selected a global shot of Mercury containing terrain never seen by spacecraft eyes. "It was extremely exciting," says science team member Clark Chapman. "I was just overwhelmed."

MESSENGER flew by Mercury at 19:04:42 UTC (11:04:42 PST) on January 14, 2008. It approached with a crescent view of the planet. On approach, all the Sunlit terrain visible to MESSENGER's cameras was terrain that had been previously imaged by Mariner 10 more than 30 years ago. MESSENGER's closest approach was on Mercury's night side. As it departed, its view was of a gibbous Mercury, with Sunlight on areas of Mercury never imaged by Mariner 10. It took several days to return all the images and data from the encounter, but as of today, all the science data from the encounter is safely on Earth.

Seeing Mercury Afresh

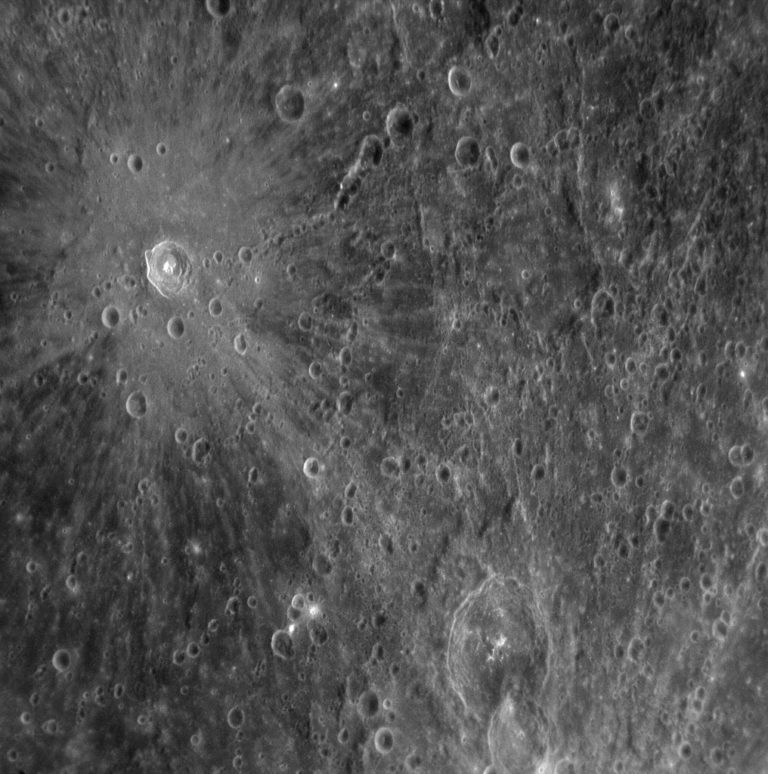

"We're poring over the pictures, and there's spectacular things to see, not just on the unseen side, but also on the 'seen' side," Chapman says. "We're actually really surprised that the pictures we have of the side of Mercury that we've seen before reveal much greater detail than Mariner 10." Mariner 10 had a television camera, while MESSENGER carries a modern CCD camera that provides much sharper images. However, the difference in detail has at least as much to do with the angle of the Sun as it does with the differences between cameras. Chapman pointed to a picture of a crater, Vivaldi, that had been imaged by Mariner 10, seen anew in a MESSENGER image. Chapman says that the Mariner 10 image "revealed a circular feature, but you could see no topography at all. Many of the things around this crater were completely invisible in Mariner 10 images."

"The lighting angle makes all the difference," Chapman continued. "Many parts of Mercury that have 'been seen' by Mariner 10 have been seen with high Sun, so you see no topography at all, and you miss very large craters. For looking at all the colors and brightness of the surface, high Sun is good, but for looking at geology, you want low Sun." Mariner 10 had no chance to observe different parts of Mercury at different Sun angles because its mission consisted of three brief flybys of the planet, all at the same time in Mercury's solar day. And Mercury rotates so slowly that the Sun angle changed almost not at all during each individual encounter. As a result, although Mariner 10 flew by Mercury three times, it saw only one half of Mercury's surface Sunlit, and of that half, only a tiny area ringing the planet's dawn-dusk boundary was seen with low Sun angles sufficient to show Mercury's topography. MESSENGER's three flybys of Mercury will have a similar problem, covering only a tiny portion of Mercury's surface at low Sun angles. However, once MESSENGER enters orbit, Chapman says it will image spots on Mercury at a variety of Sun angles, both high and low, permitting both the study of Mercury's surface coloration and the study of its topography.

Scientists are just beginning to form their first speculative ideas about the new features of Mercury that MESSENGER has revealed, and are being cautious about expressing those speculations publicly. However, Chapman predicted that "there's plenty of discoveries coming in the near future." Part of the science team's caution results from the fact that it's all too easy to see features on Mercury that look similar to other places in the solar system and assume that the same processes prevailed.

But Mercury is a different planet with a unique and complex geologic history that will only slowly be unraveled, says MASCS instrument scientist Noam Izenberg. "Everywhere you look, there's something new. It's beyond words. New views of things -- types of craters we haven't seen before -- things similar to what we've seen on the Moon, but they'renot, or similar to Mars, but they're not." As one example, Izenberg pointed out that Mercury has a lunar-like crater density, where fresher craters overlap older craters which overlap older craters, a state that leads scientists to conclude that Mercury's surface has seen little significant geologic activity for most of the age of the solar system. Yet, in some places, among the craters, there are smoother "intercrater plains" that have somehow had their craters erased.

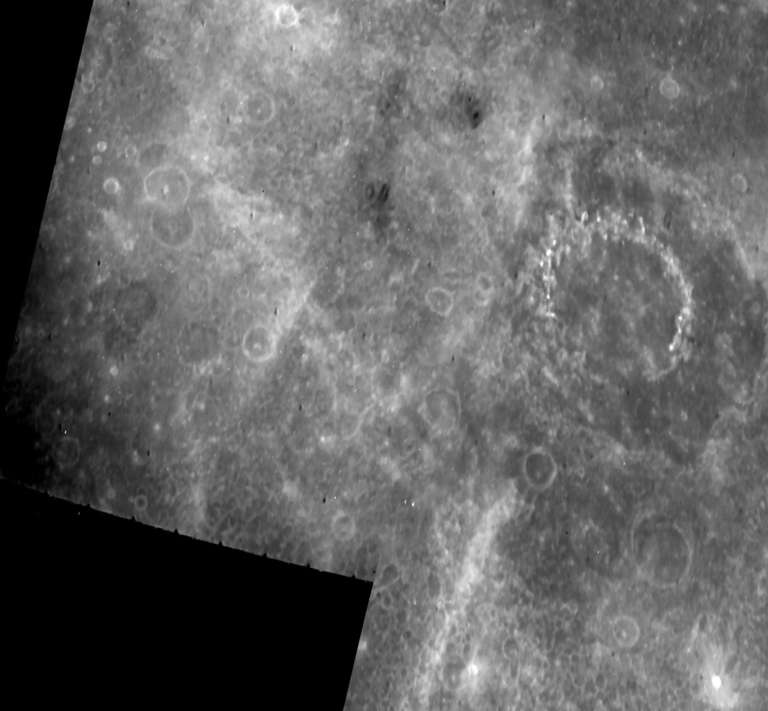

The high-resolution image below illustrates the challenges faced by the science team in interpreting Mercury's history. Near the bottom is a large, relatively fresh crater with a terraced rim. Terraces form in such craters immediately after the impact, as the steep wall of the crater collapses and slides inward. This collapse and slumping should have produced a rough crater floor, yet the interior of the crater is quite smooth but for a few small craters. Outside the crater, the surrounding plains are peppered by chains of secondary impact craters that formed with the large crater as blocks of ejecta sprayed outward from the impact site and slammed to ground. One way to understand the relative timing of the impact event and whatever geologic activity smoothed out the crater's interior floor, geologists will count the craters that formed on the large crater's ejecta blanket and compare that number with the count of small craters that have formed on the large crater's smooth floor. However, to do that, they must determine which of the small craters outside the large one were secondary to the original impact, and which ones came much later. The caption released with the image sums up the challenge: "these flat-floored craters both illuminate and confound the study of the geological history of Mercury."

Now that all the data is safely on the ground, the science teams are madly calibrating it and attempting to make sense of it. Even at this very preliminary stage, there are surprises, Izenberg explains. His primary responsibility is for an instrument called MASCS, which consists of two spectrometers, which read how brightly solar radiation is reflected from points on Mercury's surface and in its extremely thin atmosphere, information that can eventually be translated into measurements of the mineral composition of the surface and gas species in the atmosphere. "We've completed the initial calibration to take a look at the spectra of the surface. The ground track was mostly equatorial, and crossed over some interesting stuff. We also had a good couple hundred spectra just to the south and east of the crater Mozart. Those areas were seen [in images from] Mariner 10 as well as MESSENGER during the flyby, so we can do some direct comparison of the imaging and mineral composition of parts of the surface. We clearly see some variations."

It's too early in the calibration process to say much about what those variations mean, but Izenberg provided a teaser: variations in albedo (the brightness and darkness of the surface) seem to be more extreme than he expected. "There are some really, really bright spots and some really, really dark craters, too. On a local scale, there seem to be some fairly strong variations in albedo. On the whole, the planet is fairly uniform, but there are different spots that are quite striking."

Threading the Needle

All of MESSENGER's science plans had to be orchestrated months in advance, down to the precise angles at which the cameras would be pointed to capture these images. The last adjustment to MESSENGER's pre-flyby trajectory took place on December 19, 2007, nearly a month before the Mercury encounter. Even slight errors in the position or timing of MESSENGER's close approach could disrupt the carefully planned imaging sequences, causing Mercury to be out of its expected position in the camera frame.

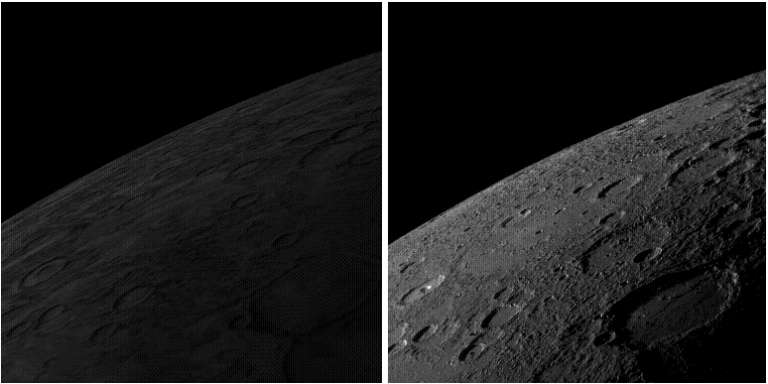

Fortunately, MESSENGER's targeting was spectacularly precise, as MESSENGER mission design engineer Jim McAdams explains. "The distance between the target and actual periapsis [close approach] points was 8.25 kilometers [5.13 miles]. The difference between target altitude (200.07 kilometers) and reconstructed altitude (201.50 kilometers) was 1.43 kilometers [0.89 miles]. It's like sending an object from Miami, Florida to Seattle, Washington and missing the target 'keyhole' by 6.4 centimeters [2.5 inches]." The precision in MESSENGER's targeting translated directly to precision in pointing of its instruments for MESSENGER's science observations; McAdams provided the following illustration of predicted (left) and actual (right) appearance of one of MESSENGER's high-resolution images of a small area on the edge of Mercury's crescent, taken as MESSENGER approached the planet.

Over the next two weeks, the MESSENGER team plans to release images at the rate of a few per day; a post-flyby press conference with initial results is currently planned for January 30. But the date that most of the science team members are looking forward to is their first presentation of MESSENGER's first data from Mercury to their peers, at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, convened in Houston, Texas on March 10-14. The mission will next encounter Mercury on October 6, 2008, when nearly the opposite hemisphere will be sunlit.

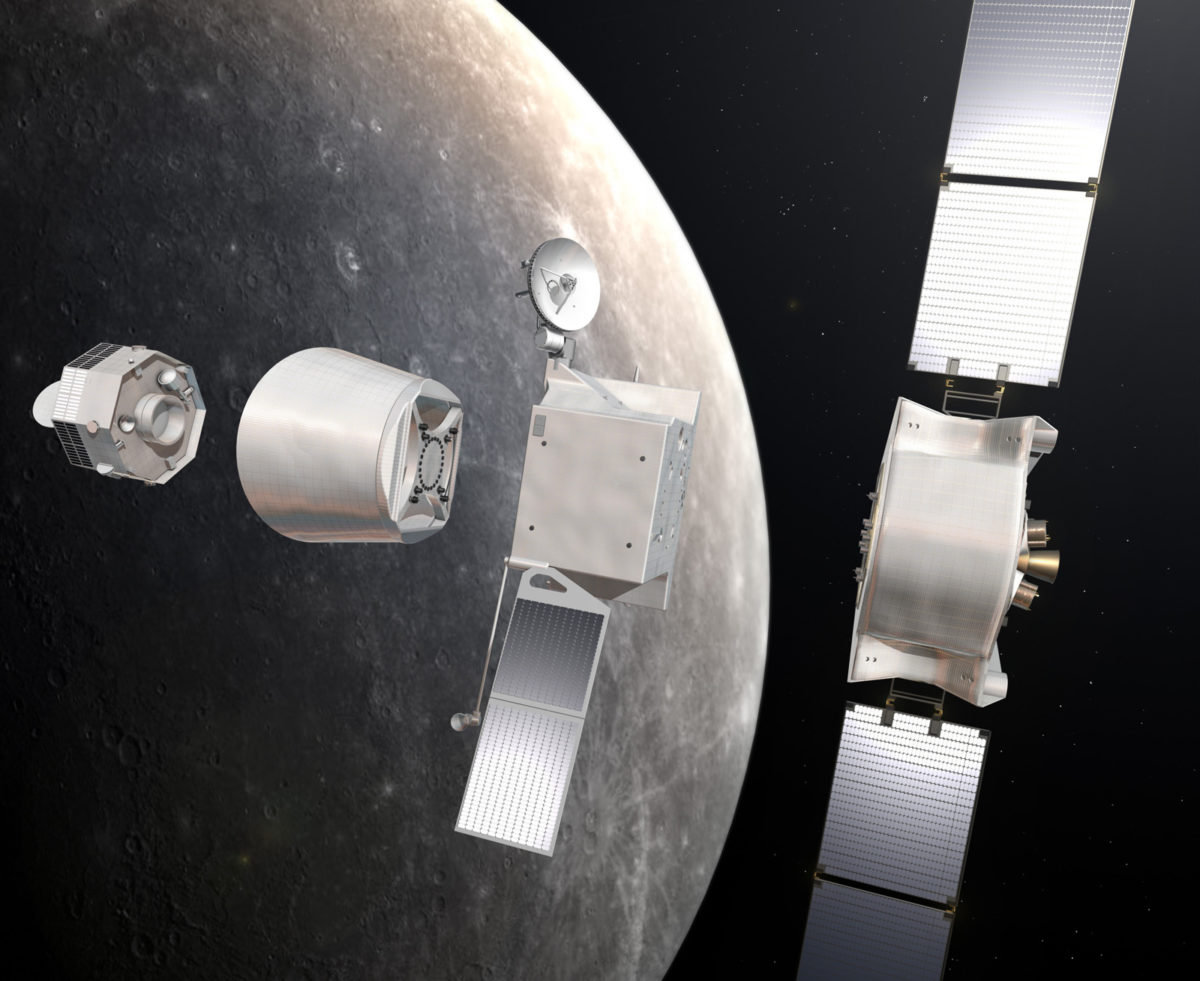

It's taken three and a half years since launch for MESSENGER to arrive at its first Mercury encounter, and it will be three more years until it goes into orbit. In all, 36 years will have elapsed between Mariner 10's initial reconnaissance of the planet and the orbit insertion of Mercury's first artificial satellite. Mercury will not have to wait so long for its next visitor, however. The European Space Agency (ESA) announced today the signing of a contract to mark the start of design and build of the next mission to Mercury, the BepiColombo mission. BepiColombo will deliver two spacecraft to Mercury orbit, one built by ESA and one to be provided by the Japanese space agency, JAXA. Launch is planned for August 2013, well after the end of MESSENGER's prime mission, and arrival for 2019.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth