A.J.S. Rayl • Feb 07, 2014

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Finds Mystery Rock, Mission Celebrates 10 Years

Sols 3534 - 3563

Mars Exploration Rover

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Maas Digital

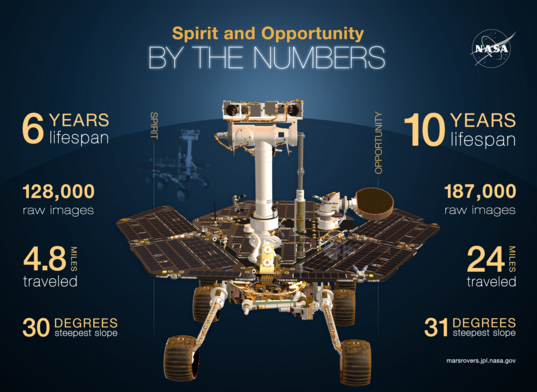

In the storied history of the Mars Exploration Rovers (MER) mission, January 2014 will likely be remembered as one of the most memorable months of all. Not only did the mission cross a huge milestone—10 years of surface of operations, but the science team published a landmark paper offering up evidence that billions of years ago—before the impact that made Endeavour Crater – Meridiani Planum was a pretty inviting place, an environment with water humans could drink, water where life could have emerged. And, Mars threw a new mystery at Opportunity, a rock bizarre enough to keep the robot field geologist busy all month.

"Mars keeps surprising us, just like it did the first week of the mission," said Steve Squyres, MER principal investigator of Cornell University, during an interview with the MER Update this month. Opportunity had moved slightly at the end of December, to turn her attention to an outcrop, but then when the rover turned back around, he said, "we saw this rock sitting where it hadn't been just 12 sols [Martian days] before." White around the outside, it features a deep, dark red interior. "It looks kind of like a jelly doughnut – and it's unlike anything we've ever seen on Mars," he said.

The MER team thinks it has a plausible explanation for the rock's sudden appearance or re-location to the slab of bedrock the rover had previously found to be clean of any surface rocks. Even on Mars, rocks don't just appear, as far we know. But the timing for the latest Martian mystery was perfect. The geologic pastry popped up just after the MER 10 celebrations began in Washington DC.

A Martian "jelly doughnut" mystery

The seemingly sudden appearance of a rock—about the size of a good all American doughnut or "Danish," as one of the JPL engineers clarified – caused much speculation at Endeavour Crater in January 2014. Primarily bright-toned, nearly white, Pinnacle Island's middle is deep red in color. The leading hypothesis is that one of the rover's wheels knocked Pinnacle Island to this position. By flipping it upside down, the rover gifted the MER scientists with the opportunity for Opportunity to examine the underside of a Martian rock. Pretty Martianally cool surprise for the 10thAnniversary.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

Ten years ago, Spirit and Opportunity set out for three-month excursions of Gusev Crater and Meridiani Planum. No one then even dreamed that one of them would still be working hard and returning jaw-dropping data a decade later. "We would have been surprised to have lasted a year," acknowledged Squyres. But Opportunity—the rover that loves to rove—completed 10 Earth years of exploring at sol's end January 23rd.

The story of how the twin robot field geologists came to be designed, built, and buttoned-up for launch in just 34 months, and how they survived the largest solar flare then on record en route to the Red Planet is a harrowing one—more of which will be told in a MER Special Update: The Magic of MER and 10 Years of Roving Mars to be posted soon. But long story short, Spirit and Opportunity defied all the odds at every turn and "rocked" the landings.

Spirit bounced down into Gusev Crater at 8:35 pm January 3, 2004 PST, followed three weeks later by Opportunity, which rolled right into a small crater at Meridiani Planum. They took the world by storm and then roved on, meeting their science and engineering objectives and making important discoveries about ancient wet environments that long, long ago could have supported microbial life on Mars. And, in the hundreds of thousands of pictures that have streamed onto our computers screens, the rovers made Mars less alien. We can imagine standing on these landscapes that seem, somehow, so familiar.

Spirit worked for more than six years in the tough, rocky, and sandy terrains of Gusev. Then in April 2009 it became stuck in a sandy snare near Home Plate, an eroded over volcano that it had been studying for several years. As its fourth winter set in, the rover sent a communiqué in March 2010, and then slipped into its first ever hibernation. Despite more than 1300 attempts to make contact, Spirit never responded. NASA declared its mission over in May 2011.

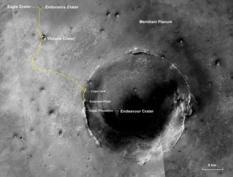

Opportunity roved on arriving at the 22-kilometer (13.67 mile) diameter Endeavour Crater in August 2011. Along the Cape York segment of the crater's rim, it has roved deeper into the planet's geologist past than ever before, to the Noachian Period some 3.7 to 4.2 billion years ago. "And everything changed," said Squyres.

The rover's findings have enabled the science team to continue to find new things—the "jelly doughnut" rock being the latest—and gather the planetary pieces to piece together into the bigger story of when Mars looked more like Earth for landmark work (more on that in a bit), and to consider what happened that turned the planet into the cold, seemingly desolate place it is today.

As 2014 rang in on Mars, Opportunity was investigating exposed outcrop targets in an area dubbed Cook Haven, located on Murray Ridge in the Solander Point section of Endeavour's rim, the next major rim segment south of Cape York. Positioned on the edge of an outcrop called Cape Darby, the rover was looking for clay minerals that orbital observations indicate are there, but it had still not uncovered the oldest rock layer there, Matijevic Formation bedrock.

"Cape Darby, which is at Cape Douglas, the outcrop area, is an impact breccia, because you can see the clasts and the matrix," said Ray Arvidson, MER deputy principal investigator, of Washington University St. Louis.

Breccias are rocks composed of broken fragments of minerals, rocks, and stuff cemented together by a fine-grained matrix that can be either similar to or different from the composition of the fragments. "It looks more like Shoemaker Formation impact breccia [formed by the impact that created Endeavour] than anything else, but we're trying to figure out what these breccias are and how they fit into the overall stratigraphy of the crater rim."

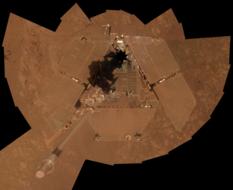

The New Year began as good as any Martian winter day possibly could begin. Mars, as the MER team likes to say, was cooperating. The planet whisked up some little gusts that blew good tidings to solar-powered rover on December 31, 2013, clearing some of the accumulated dust off its arrays. And then Mars repeated the favor on January 1, 2014, gifting the rover with a boost in power for the start of 2014.

The road less traveled

The gold line on this image shows Opportunity's route from the landing site, in upper left, to the area it is investigating on the western rim of Endeavour Crater as of the rover's 10th anniversary on Mars, in Earth years. The rover is currently ascending and working along Murray Ridge at the Solander Point segment of Endeavour Crater's rim. The base image for the map is a mosaic of images taken by the Context Camera on MRO, built and operated by Malin Space Science Systems. This traverse map was made by Larry Crumpler, a MER science team member, at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science, Albuquerque. The 5-kilometer scale bar is 3.1 miles long. The diameter of Endeavour Crater is about 22 kilometers (14 miles). North is up. If all goes as planned, Opportunity will depart for Cape Tribulation in the spring. The full-resolution version is available here.NASA / JPL-Caltech / MSSS / NMMNHS

At the same time, as the Martian winter reached for its depths in January, the weather was milder than it might have been. The bump in power and calm climate pushed the rover's energy levels comfortably above the winter margins, pretty much assuring that Opportunity will be able to continue to rove along Murray Ridge and work through the winter solstice in mid-February, and on into spring.

So, after finishing up analysis on targets at Cape Darby—using its "hand lens" or Microscopic Imager (MI) to take extreme close-up pictures and its Alpha Particle X-Ray Spectrometer (APXS) spectrometer to glean the chemical composition of the outcrop—Opportunity turned "bumped" or drove just a short way to a new target nicknamed Cape Elizabeth on Sol 3540 (January 7, 2014).

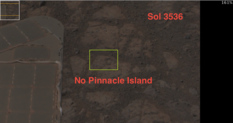

As the rover was preparing to check out Cape Elizabeth on the following sol, 3541 (January 8, 2014), MER team members were startled to see the strange white rock with a deep red interior in the new images of an area the rover had been to not long before. Team members double-checked: the bizarre looking rock—which came to be called Pinnacle Island – had definitely not in the images taken a couple of weeks before.

Most likely, they rationalized, Pinnacle Island fell into the scene from just uphill, where Oppy had completed a turn-in-place, a kind of pirouette, dragging its right front wheel across ground some sols before. "We don't think anything particularly exotic happened here," Squyres said, quickly noting they have two working theories. "We think the process of that wheel moving kind of flicked it, Tiddly-Winked it to the location where we now see it. This is the more likely scenario. The other theory is there's smokin' hole in the ground somewhere nearby and it's a piece of crater ejecta."

On further analysis, Jim Rice, of the Planetary Science Institute and MER Geology Team leader, refined the appearance of Pinnacle Island to have occurred sometime within four Martian days, between sols 3536 and 3540.

There were, Arvidson added later, other stony suspects, "smaller pieces" found in other images. However Pinnacle Island landed in the work volume, the area where the rover's immediate target is and where it takes the most pictures when it's working. And given its size and appearance, this rock couldn't be missed. It may have flipped upside down. "If that's what we're seeing, the underside of this rock hasn't been exposed to the Martian atmosphere for perhaps billions of years," said Squyres.

That's the kind of thing that can make field geologists really excited and so the MER team had Opportunity hunker down. During the second and third week of January, the robot field geologist took pictures of Pinnacle Island and began a series of off-set examinations on the rock, homing in on one spot with its MI and then placing the chemical detecting APXS on it, then moving the instrument just a bit to another adjacent spot, and then to another spot and so on. It's a technique that allows the scientists to figure out what the doughnut or white part of the rock is composed of and what the jelly or deep red interior part might be, and what they have in common.

Opportunity's post-dusting selfie

Opportunity snapped the component images for this self-portrait about three weeks before completing a decade of work on Mars. Using its panoramic camera (Pancam), the robot field geologist took the images from Jan. 3-6, 2014, a few days after winds removed some of the dust that had been accumulating on its solar panels. This image is presented as a vertical projection. The mast on which the Pancam is mounted does not appear in the image, though its shadow does. The full-resolution version is available here.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / Arizona State University

"We've taken pictures of both the doughnut part and the jelly part and the first data on the composition of the jelly yesterday show it is like nothing we've ever seen before," Squyres said in mid-January. "It's very high in sulfur and magnesium, with twice as much manganese as anything we've seen on Mars."

Those findings and the fact that the rock is a tough target, in shape and size, kept the rover focused on Pinnacle Island for the rest of the month. On Sol 3554 (January 22, 2014), Opportunity struggled with a difficult wrist move trying to reposition the APXS and just couldn't make it happen. It was not, however, a lost sol. The rover punted, so to speak, lifting its arm out of the way to take a series of images for a 13-filter, stereo, color Panoramic Camera (Pancam) picture of the Martian jelly doughnut. Then it put the APXS back down on the same target on the rock.

From the ongoing stream of data coming down, the dark red stuff appears to be "iron manganese oxide of some kind," while the surrounding white part "represents some kind of sulfate," Arvidson suggested at month's end. "These are all minerals and elements soluble in water." It could be Pinnacle Island is "an ancient water-laid deposit" from the Noachian Period some 4 billion years ago, "or it could be from a more recent period," he added.

"We're completely confused and having a wonderful time," summed up Squyres.

Despite the trickiness of examining Pinnacle Island up close, Opportunity persevered, an indication of how much the science team members want to find out what this rock is, when it was formed, and what it has to say about the ancient past. But it didn't get any easier.

The rover attempted a very difficult, tiny turn-in-place to move just 1.4 degrees to reach a new location on the target, on Sol 3555 (January 23, 2014). The initial wheel motion achieved sufficient turn magnitude, but the wheel straightening undid that motion so Opportunity didn't quite reach the target position. Such small motions are very difficult to achieve with the rover—remember it has a jammed right front wheel – so the rover took care of other routine business as it crossed its 10-year milestone.

And then – there it was

This before-and-after pair of images of the same patch of ground in front of Opportunity 13 days apart documents the arrival of Pinnacle Island onto the scene. The one on the right, with the newly arrived Pinnacle Island, is from Sol 3540 (Jan. 8, 2014).NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

Two sols later, Sol 3557 (January 25 2014), Opportunity tried the maneuver again using a 'tank turn' technique and succeeded. It then took some pictures with the Pancam and conducted a routine measurement of argon in the atmosphere with the APXS, before putting the chemical detector down on a new spot on Pinnacle Island for analysis.

The robot field geologist checked out every aspect of Pinnacle Island it could, taking more MI pictures on Sol 3560 (January 28, 2014) to create a mosaic of the new location on Pinnacle Island, and then put the APXS down on that spot.

Despite a jammed right front wheel, arthritic arm and the loss of its two mineral detecting instruments, Oppy is actually going strong, although she did suffer a "senior moment" in January, said John Callas, MER project manager, of JPL. These "senior moments" occur from time to time because of a corruption in the rover's Flash memory. The engineers have a fix, but the corruption has to get worse first, so for the time being the rover's "senior moments" are "operational annoyances," Callas said, and "not a health issue." Past that though, "almost nothing has changed in health and status of the rover in the past year," he reported.

Refining the timeframe

On further analysis, James Rice, the MER Geology Team lead, winnowed down the timeframe of Pinnacle Island's appearance to four Martian days. In this image from Opportunity's Sol 3536 (Jan. 3, 2014), it is clear the bizarre Martian rock has yet to show.

On further analysis, James Rice, the MER Geology Team lead, winnowed down the timeframe of Pinnacle Island's appearance to four Martian days. In this image from Opportunity's Sol 3536 (Jan. 3, 2014), it is clear the bizarre Martian rock has yet to show.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

Meanwhile, down on Earth, humans celebrated the MER mission's extraordinary achievement in a variety of press conferences, presentations, and exhibits, each of which showcased the adventures and achievements of Spirit and Opportunity.

Smithsonian's National Air & Space Museum (NASM) on the Mall in Washington DC opened its MER exhibit in early January. The exhibit features a full-scale model of the MERs and more than 50 mosaic and panoramic photographs taken by Spirit and Opportunity. MER mission team members chose the images based on both scientific and aesthetic content. The collection includes most everyone's favorites, from a view of the Sun setting over the rim of a crater, to dunes rolling like waves, to a shot of rover tracks disappearing over the horizon, and more from the intrepid twin rovers that took us on the first overland expedition across Mars. The exhibit will be open through September 14, 2014.

In conjunction with the museum opening, NASA Headquarters joined the Smithsonian in hosting a morning press briefing January 7th at the museum that was webcast and broadcast on NASA TV. Tom Waters, senior scientist and chair for the National Air and Space Museum's Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, served as the primary host, introducing two panels.

The first panel, moderated by Pamela Conrad, of NASA Goddard, a Curiosity rover scientist, discussed the achievements of Spirit and Opportunity and some of what we know now about Mars that we didn't know before this mission. From Squyres to Dave Lavery, a program executive for the Mars Exploration Program, and John Grant, the supervisory geologist at the museum's Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, MER science operations working group chair, and curator of the MER 10 exhibit, the panelists covered the bases, reviewing NASA's theme strategy and the role MER played.

James Green, the director of planetary science at NASA HQ moderated the second panel that discussed NASA's plans on Mars and the importance of current robotic missions to future human missions to Mars—and the hopes for and chances of finding life, past or present, there. That panel included Mary Vortek, head of NASA's astrobiology program at NASA HQ; John Connelly, the chief exploration scientist working at Human Exploration Directorate at the Johnson Space Center (JSC); five-time shuttle astronaut John Grunsfeld, the associate administrator of the Science Mission Directorate at NASA HQ; and a young lady who hopes to be among the next generation of explorers, Alissa Carter, the first winner of NASA Passport Program.

[You can view the press briefing here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IMl7Q0KHcQ4. Also, NASA's mission highlights, including videos and a gallery of selected images from both rovers is at http://mars.nasa.gov/mer10/.]

On January 16th, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where all of NASA's Mars rovers have been designed, built, and managed, held a public event in Beckman Auditorium on the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) campus in Pasadena, California, just a few miles from JPL. John Callas served as emcee, opening by saying "We are here to celebrate that which should not have been…" He then went on to introduce JPL Director Charles Elachi who credited "the team and thousands of people who worked on the mission.

Squyres, Callas, and Bill Nye, chief executive officer of the Planetary Society and designer of the Mars Dial onboard the MERs also spoke, focusing on the achievements and adventures of the rovers. And a panel of four JPL engineers and MER team members – Ashley Stroupe, MER's first woman driver; Mike Seibert, lead flight director for MER (who was in college when the twins landed); Bill Nelson, chief of MER engineering; and newbie Heather Justice, a MER software engineer and rover driver in training (who was in high school when the rovers landed), shared stories from the trenches (some of which will be covered in the forthcoming MER Special Update.)

Smithsonian Celebrates MER 10

Smithsonian's National Air & Space Museum on the Mall in Washington DC opened its MER exhibit in January. The exhibit features a full-scale model of the MERs and more than 50 mosaic and panoramic photographs taken by Spirit and Opportunity selected by MER mission team members. The exhibit will be open through September 14, 2014.Air & Space, Smithsonian Institution

The evening of mission highlights and memories packed the hall, drawing a crowd that included original team members, including Mark Adler, who, one could say, started it all, by pulling together JPL team to propose a rover back in 2000, Rob Manning, the entry, descent, and landing manager, whose team guided Spirit and Opportunity to their Martian homes, and the first project managers Pete Teisinger, Richard Cook, and Jim Erickson, as well as plenty of admitted rover lovers and self-proclaimed engineering geeks. [You can view the event here: http://www.ustream.tv/recorded/42795898]

The following week, on January 23rd, mission officials—Michael Meyer, lead scientist for the Mars Exploration Program at NASA Headquarters, Washington; Arvidson, Callas, and Squyres—held a press conference at JPL to mark the day Opportunity would complete her milestone. The conference also coincided with the publication of the MER science team's latest paper. Published in the January 24, 2014 edition of the journal Science, "Ancient Aqueous Environments at Endeavour Crater, Mars" logged a milestone of its own.

In brief, the MER science team, led by Arvidson, the first author of the paper, concluded that billions of years ago, an ancient wet environment that was milder, warmer, wetter, and older than any the rover had previously found could have offered a habitat for life to emerge. The MER researchers based their conclusions on the evidence of clay minerals, in the form of iron-rich smectite and a more aluminous smectite that Opportunity ground-truthed at Matijevic Hill, and believe the wet conditions that produced these smectites preceded the formation of the Endeavor Crater about 4 billion years ago.

"These rocks are older than any we examined earlier in the mission, and they reveal more favorable conditions for microbial life than any evidence previously examined by investigations with Opportunity," Arvidson summed up later. "The father back you go at Endeavour, the better it gets," he told the MER Update.

As reported in various MER Updates posted during the last two Earth years: To find rocks for examination, the rover team steered Opportunity in a loop, scanning the ground for promising possibilities on Matijevic Hill, starting in late August 2012. The search was guided by a mineral mapping instrument on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), a spacecraft that did not even arrive at Mars until 2006, long after Opportunity's mission was supposed to end.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / Arizona State University

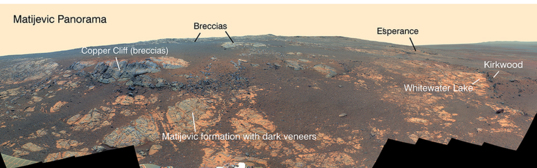

A once habitable Mars

Opportunity used its panoramic camera (Pancam) to capture this false-color panorama of the Matijevic Hill area on the Cape York segment of the eroded, western rim of Endeavour Crater. The breccias are jumbled rocks amalgamated together, interpreted at this site as material tossed by the impact that excavated the crater. Whitewater Lake and Esperance are where the team ground-truthed the presence of phyllosilictaes in the form of iron-rich smectites and aluminous smectites. The full-resolution version can be found here.Opportunity had been enlisting images from the HiRISE camera to chart its paths and avoid dangers for years. In recent years, when it lost the Mössbauer, the second of its two mineral detectors—the Miniature Thermal Emission Spectrometer (Mini-TES) was damaged in the planet-encircling dust storm of 2007—the team heralded for its ability to create ingenious "workarounds" to problems simply enlisted the infrared mapping instrument, the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM), as its newfound mineral detector from on high. Both HiRISE and CRISM are onboard MRO.

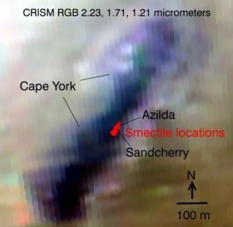

Beginning in 2010, CRISM began detecting minerals at Endeavour Crater, from on high. After Opportunity arrived at Endeavour, Arvidson, who is also a co-investigator on CRISM, requested CRISM acquire data of Cape York in a mode known as along-track oversample (ATO), which, basically, sharpens spatial details. From that data, he was able to create a pixel-by-pixel map showing where the reflectance signature of the smectites that CRISM was detecting was coming from, a place that soon would be christened Matijevic Hill, after the late Mars rover pioneer, JPL's Jake Matijevic.

The Opportunity team set a goal to examine this mineral in its natural context—where it is found, how it is situated with respect to other minerals and the area's geological layers—a valuable method for gathering more information about this ancient environment. And beginning in late August 2013, the rover spent 200 sols or Martian days working on that objective on the slopes of Matijevic Hill.

MER's workaround mineral detector map

The red areas designate the location where CRISM detected smectite clay minerals on Matijevic Hill, according to Ray Arvidson's pixel-by-pixel map. They are positioned directly over Whitewater Lake outcrop. "That's where the clays are," said Steve Squyres. "Case closed."NASA / JPL-Caltech / JHUAPL / R. Arvidson (WUSTL)

In the end, Arvidson et al., found the "signatures are associated with fine-grained, layered rocks" that contain spherules, either of diagenetic origin [formed by water and/or erosion during or after rock formation] or impact origin [like lapilli from volcanoes or meteorites]. "The layered rocks are overlain by breccias and both units are cut by calcium sulfate veins precipitated from fluids that circulated after the Endeavour impact," they added in the abstract that opens the article.

Additionally, the MER scientists found evidence for more aluminous smectites in the fractures of what are known now as Matijevic Formation rocks. "Compositional data for fractures in the layered rocks suggest formation of aluminum-rich smectites by aqueous leaching," they wrote. "Evidence is thus preserved for water-rock interactions before and after the impact, with aqueous environments of slightly acidic to circum-neutral pH that would have been more favorable for prebiotic chemistry and microorganisms than those recorded by younger sulfate-rich rocks at Meridiani Planum."

It is, simply, landmark research on Mars—and it's coming a decade into a 90-day mission.

"It isn't how long the rover has lasted, but how much science it is still doing," Callas said—once again.

As for the future at Mars, Meyer delivered some good news during the January 23rd news conference: "We're finding more places where Mars reveals a warmer and wetter planet in its history," he said. "This gives us greater incentive to continue seeking evidence of past life on Mars."

Then came the concerning news: MER goes before a Senior Review on Earth this coming spring. That committee will determine whether the $14 million annual operating cost is worth Opportunity continuing on.

Seems hard to believe there would be any question. The discoveries made by Spirit and Opportunity have not only shaped our knowledge of Mars and ultimately may impart planet-saving knowledge about Earth – but Opportunity is the longest-lived reworking robot on another planet, making some of the best discoveries to date. More than that, Opportunity is a rover hero, an international icon, an ambassador for NASA, for the United States, for Earth on Mars—loved around the world.

And, there are a lot of planetary science missions still operating long past their primaries, Meyer said, "all doing good work," and not enough money in NASA's budget to fund them all. Time, as the saying goes, will tell if the rover that loves to rove will be allowed to rove on. [To view the press conference: http://www.ustream.tv/NASAJPL]

Oblivious to achievements and concerns, Opportunity spent her 10th anniversary quietly hunkered down over the Martian "jelly doughnut," 38.7 kilometers (about 24 miles) from where she landed on January 24, 2004. That may not seem so far in terms of distance, but in terms of technology and engineering and operations it is a first small step that will some day lead to humanity's giant leap onto Mars.

Roving on

As the Martian winter progresses toward solstice on February 14th, Opportunity will continue exploring the outcrops in Cook Haven. Then, when spring blooms in Mars' southern hemisphere, it will continue south along Murray Ridge, seeking out the locations of more clay minerals detected from orbit. The rover's future looks bright, promising discoveries that will unravel more ancient mysteries. "As long as Opportunity keeps going, we'll keep going," said Steve Squyres.NASA / JPL-Caltech

"It's like Eagle Crater all over again," Squyres said of Endeavour Crater. "That's the beauty of this mission. I used to think that no matter how long the rovers lasted, at some point we would get to the stage where we could sit back and fold our arms and say with a sense of self-congratulations that we did it. 'We're finished. Yeah, the rover is still alive but we've learned all we could at this place.' Mars isn't like that. I've come to realize—and this was true when we lost Spirit and it will be true next week or 10 years from now when we lose Opportunity—there will always be something tantalizing just beyond our reach that we didn't quite get to."

With the 10th anniversary milestone now in the rear view mirror, the MER ops team and its veteran rover are focused on the future. "There's more good stuff ahead," said Squyres.

Once the rover finishes the examination of Pinnacle Island, the plan calls for it to back up and take a look at the possible places from where Pinnacle Island and the other little stones popped out to fall into Opportunity's view – its solar arrays have been blocking the suspected part of the hill from view. Then, with the best winter power levels this rover has had in three Martian winters, averaging just above 350 watt-hours more than 1/3 of its full capability, Opportunity will move on to another exposed outcrop in Cook Haven, just 3 meters away. Called Green Island, this outcrop also hints of clay minerals.

"It's topographically the lowest outcrop we see in Cook Haven," said Arvidson. "We're not sure if it's far enough down to be Matijevic Formation [the oldest, Noachian Period strata]. It may still be Shoemaker breccias [deposited by whatever formed Endeavour Crater], but we'll go there, and then go up the ridge, looking at the strata as we go."

As the Martian winter progresses toward solstice on February 14th, Opportunity will continue exploring the outcrops CRISM data show to be harboring clay minerals in Cook Haven. When spring blooms in Mars' southern hemisphere, the robot field geologist will continue south along Murray Ridge, seeking out the locations of more clay minerals detected from orbit, promising new discoveries, new clues that will help unravel more ancient mysteries, and advance plans for human missions to the planet in the 2030s.

"We have some an exciting period of discoveries ahead of us, maybe some of the best science yet to come," said Squyres. "As long as Opportunity keeps going, we'll keep going."

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth