A.J.S. Rayl • Feb 04, 2017

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Celebrates the Big 1-3, Begins 14th Year of Ops!

Sols 4600 - 4630

As people all around Earth partied and watched fireworks signal the launch of 2017, some 45 million miles away the New Year got off to a start that was unprecedented in every good way: the Mars Exploration Rover (MER) mission completed its 13th Earth year of surface operations and Opportunity drove the first overland expedition of the Red Planet into its 14th year, giving the world something to be universally proud of in January.

More than 13 years on Mars on a mission that began as a three-month tour. Talk about right stuff. “I don't think anyone in 2004 thought that we'd be commanding this bad girl in 2017,” said MER Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson of Washington University St. Louis. “It's just truly amazing.”

And Opportunity is not slowing down. In fact, this robot field geologist is on her way to an ancient gully and traversing now some of the most treacherous terrain she has ever encountered to get to what just may be the most significant research site the mission will visit on its quest to “Follow the Water” and find evidence for past environments that once may have been inhabitable.

“This gully has been calling us for years now,” said MER Principal Investigator, Steve Squyres, of Cornell University. “We saw this thing a long time ago and for the longest time I didn't even dare talk about it, because it seemed so impossibly far off.”

They never would have dreamed of a landing site that had gully formations, because it would have been just too rugged to land on. “But once we got to the planning stages for this extended mission, it was clear we were getting close and that it was in reach and could conceivably be the next goal for the mission,” said Squyres. “Now it is. And the only thing that has enabled this is the incredible longevity of this vehicle.”

All the adjectives and descriptors one could conjure about this rover’s longevity have been used many times over: amazing, incredible, extraordinary, remarkable, fantastic, astonishing, unbelievable, mind-blowing and, even supercalifragilisticexpialidocious. You can’t find a right word that hasn’t been used again and again.

“Yes, we have run out of superlatives,” said MER Project Manager John Callas, of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the birthplace of all NASA’s Mars rovers. “What is noteworthy is that Opportunity's good health has been remarkably stable for years on the surface of this hostile world. And importantly, we have the greatest adventure ahead of us, the gully, remarkable for such a long extended mission.”

The gully is a big scientific deal. The team’s work there will mark the first time a surface mission and a rover have investigated a gully this ancient up close. Given that the scientists are confident that the gully was carved by water 3 to 4 billion years ago during the Noachian Period, the epoch when Mars had water and was more like Earth, it promises to be a most revealing site. Who knows what past environment awaits discovery there? The scientists and engineers and the rover are roving on now as fast as they kind to find out.

“Opportunity is a robust yet vulnerable wanderer on a barren, unforgiving, yet strangely beautiful planet that has lasted longer, traveled farther, and discovered far more than anyone ever expected,” said MER Chief of Engineering Bill Nelson, of JPL. “She begins her fourteenth year on Mars in great condition and we’re all confident that she is up to the challenge of the ambitious science campaign that’s just down the road.”

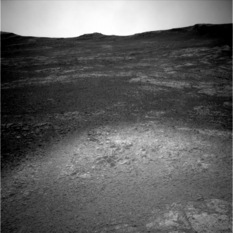

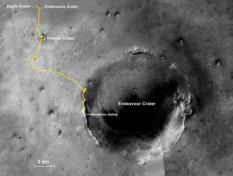

NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA

The next big attraction

Opportunity is on her way to the gully pictured above. The robot field geologist and the MER science team will be the first ever gather research and study an ancient gully, dating to the Noachian Period some 3 to 4 billion years ago, a time when most planetary scientists believe Mars had water and was more like Earth.The MER mission has become a legend in its own time. The team has won all kinds of awards and was even cited for its excellence by the U.S. House of Representatives in 2009. And the story of this legend, covered every rove of the way in the MER Update, is classic.

“I believe in the rovers because I believe in the people who built them, the people at JPL, all the subcontractors, and the people on my team,” Squyres told me in the days before the landings.

There was brilliance from the very beginning, not the least of which was the transformer-like design Mark Adler, a member of the original MER creation team and Spirit’s Cruise Mission Manager, conceived to ensconce the golf cart sized rovers in the same tetrahedron spacecraft model used by Pathfinder to deliver tiny Sojourner to Mars in 1997. Outside the team however, few people believed the rovers would land safely and complete their primary missions.

Two out of every three missions to Mars then failed. And no one had safely landed two spacecraft on Mars since NASA’s flagship Viking mission in the mid-1970s. Certainly both rovers would not succeed, so the whispering went. But Spirit and Opportunity – and Mars – had another plan.

As Opportunity neared the point of entering the Martian atmosphere the evening of January 24, 2004, all systems were “go” and looking good. "Sit back and enjoy, it's going to be an E-ticket ride," Wayne Lee, chief engineer for entry, descent and landing (EDL), calmly announced from mission control at JPL.

At 8:59 p.m., the spacecraft hit the atmosphere and then cruised through the ‘six minutes of terror’ seemingly effortlessly. Right on time, at 9:06 p.m., Pacific Standard Time (PST), Opportunity hit the surface of Mars on target in Meridiani Planum. She bounced down with a relatively light impact force of between 2 and 3 Gs, and then bounced along the surface until she rolled inside a small crater, scoring Earth’s first interplanetary hole-in-hole.

Her twin, Spirit, landed three weeks earlier in the more treacherous Gusev Crater, believed to have possibly held a lake long ago. The alpha robot had already taken her first rove, survived a freak-out when her computer got stuck in a reboot loop, and had just gotten back to work.

Two rovers. Two spectacular landings. Two missions. “We did it!” exclaimed then-JPL Director Charles Elachi.

The skeptics and naysayers evaporated in the sheer exuberant joy that lit The Lab that night. The twin Mars Exploration Rovers took the world by storm.

People all around Earth fell in love with these robot heroes the moment Spirit beeped home at 8:51 p.m. PST, January 3, 2004, safe and upright on the surface of Mars. She and the MER EDL crew made it look easy, setting the stage for Opportunity’s jaw-dropping arrival. "Everything happened the way we expected it to happen," said JPL's Rob Manning, then the MER EDL development manager, at a news briefing that followed.

"The fact that Spirit is ‘alive’ on the surface, said the first MER Project Manager Pete Theisinger, "is a very good harbinger of things to come.”

Some of those “things” began arriving within hours as Spirit’s first postcards streamed into the servers at JPL. Within 72 hours, 1.2 billion people jammed NASA and JPL and mirror websites looking for news and the pictures of this dangerous and desolate planet...pictures that at first left Planetary Society President Jim Bell, the science lead on the rover’s Panoramic Camera (Pancam) in a state of “shock and awe”...pictures that would evolve over the years into a glorious, breathtakingly beautiful album of gigantic color images of Martian landscapes that would become a hallmark of the MER mission and make Mars “a familiar neighbor,” as Callas put it.

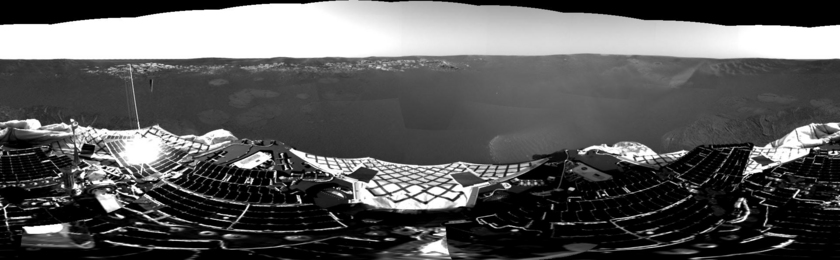

E-ticket to Mars

Ensconced inside tetrahedron-shaped spacecraft wrapped in protective aeroshells, Spirit and Opportunity took the dramatic ride through “six minutes of terror” and survived, The aeroshell broke away and the rovers safely landed three weeks apart in January, 2004. Protected by airbags, they actually bounced to landing in a design conceived by JPL’s Rob Manning, then the EDL Development Manager.NASA / JPL-Caltech

Despite Mars and the lingering naysayers, both Spirit and Opportunity successfully completed their primary missions in March 2004 and then kept on going. Their predecessor, Pathfinder's Sojourner, the little, microwave oven-sized giant on whose shoulders the twin MERs stood, was tethered by radio link to its lander, the Carl Sagan Memorial station. But Spirit and Opportunity left their landers for good and struck out on the first overland expedition of the Red Planet, advancing Mars exploration with every new site they visited.

After checking out nearby targets, Spirit picked her way across the rocky, ragged terrain of Gusev Crater for some two kilometers (about 1.24 miles) to the Columbia Hills, named in honor of the space shuttle Columbia. There, the little-robot-that-could became the first ever to scale a mountain, well, actually it was a hill, 300 feet in elevation, named Husband Hill, in honor of Rick Husband, the commander of STS-107, Columbia’s final, fatal mission. But the MERs weren’t designed for this kind of uphill motocross, and so along the way this ‘bot defined MER mettle as she faced one challenge after another.

When her right front wheel broke just before the onset of the mission’s second Martian winter, Spirit, valiantly it seemed, turned around and dragged herself and her wheel into her winter haven just in time. Then, with that broken wheel, this rover went on to uncover near pure silica and logged one of the mission’s most significant discoveries.

Years later, a group of MER scientists led by Dick Morris, manager of the Spectroscopy and Magnetics Laboratory down on Earth at NASA's Johnson Space Center (JSC), discovered that Spirit found magnesium iron carbonate – and a lot of it in a rock called Comanche on Husband Hill. It was evidence of a Martian past environment where near neutral, not acidic, water flowed, and life as we know it could have taken hold. It was a discovery that Squyres called “one of the top five findings of the entire mission.”

After nearly seven years on the harder road never traveled, Spirit ceased communication, likely silenced by the Martian winter of 2010. In the end, Spirit found evidence of slight weathering on floor of Gusev, but no evidence for a past lake. Her work in the Columbia Hills though did return evidence that revealed a moderate amount of aqueous weathering, in sulfates and the minerals goethite and carbonates that only form in the presence of water.

Opportunity meanwhile roved out of Eagle Crater and onto the shores of what may have been an ancient salty sea, and then drove some 800 meters (about a half-mile) to Endurance Crater. When she drove into the 130-meter (426.50-foot) hole in the ground, she became the first robot to drive into a crater on Mars. After a scientific spin inside Endurance, the team dreamed big and dispatched the rover, still ready, willing and able, to Victoria, a larger crater, about 730 meters in diameter, miles away. It was an impossible dream of a destination

NASA / JPL-Caltech

Holy Moley Batman!

This 360-degree panorama is one of the first images Opportunity beamed back to Earth shortly after she rolled into Eagle Crater and scored the world’s first interplanetary hole-in-one on January 24, 2004 PST. This outcropping of bedrock left the science team speechless. As MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres put it -- not only because it is the first bedrock ever found on Mars, but because it could possibly reveal whether water played a role in its formation. “Right now, I'm just in awe. I still can't find words to describe this beautiful, alien place,” he said that night.“When the rovers first landed, I remember Mike Malin located the MOC strip that had our landing site in it – this of course was before HiRISE (camera) and the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter had launched – and he rolled out the whole strip on this big long table,” remembered Squyres.

The Mars Orbiter Camera (MOC), which was an instrument built and operated by Malin Space Science Systems, was onboard Mars Global Surveyor, which launched in 1996 and was in orbit working for a decade. It was decommissioned in January 2007 when it failed to respond to commands.

“We just rolled out the MOC strip. It was big, probably four to five feet wide and many feet long,” Squyres continued. “There was little Eagle Crater and we could see Endurance Crater. We were: ‘Okay, we've got a scientific problem of epic proportions here in this little Eagle Crater, but boy if we could get over to Endurance before the end of the mission wouldn't that be great?’ And then, way, way down at the end of the strip there was this crazy thing that looked like a gear, a cog with feet. It was Victoria Crater. We were: 'Oh man, wish we had landed close to that.’”

The team would soon discover this rover really loved to rove, and after 21 months of driving, this rover made the impossible dream real. And then, after her two-year investigation of Victoria, in September 2008, Opportunity got even more ambitious roving orders – Endeavour Crater, a destination that wasn’t even a dream in 2004.

“Staggeringly large compared to anything we've seen before,” as Squyres defined it, Endeavour is 22 kilometers (13.7 miles) in diameter. ''We may not get there,” he said then, “but scientifically it is the right direction to go.”

Go, Opportunity did. Following a three-year long journey across the Meridiani Plains, finally, in August 2011, the rover pulled up to Endeavour’s western rim. It was as if the mission had begun anew.

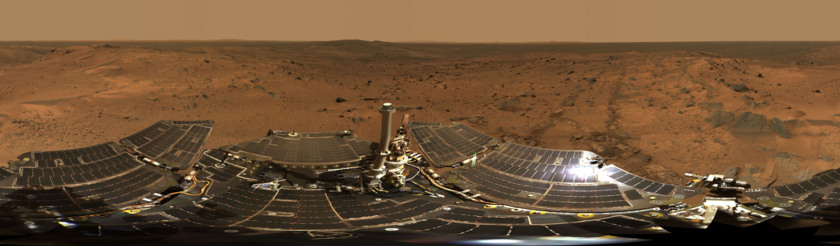

NASA / JPL / Cornell

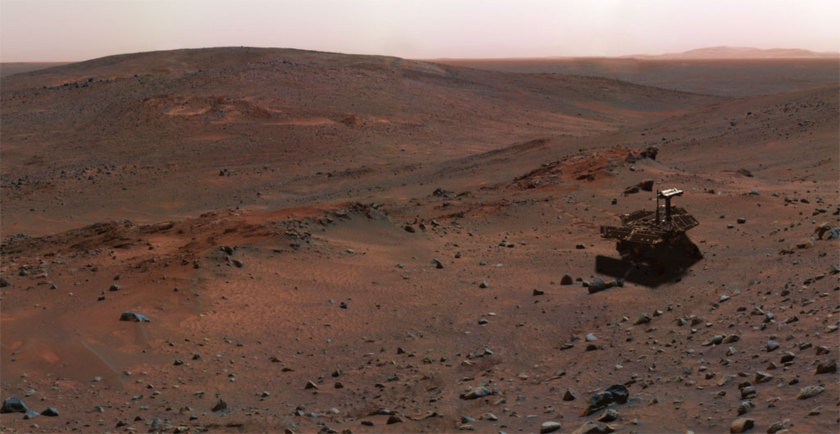

Summiting Husband Hill

This panorama, which Spirit took in August 2005, represents the culmination of Spirit's grueling ascent up Husband Hill, the tallest of the Columbia Hills, and it was a triumph. It gave the MER team its first view down into the Inner Basin and Home Plate, where the rover would spend the rest of its mission. The rover deck appears pristine; strong winds at the hill's peak had swept the deck clean.Opportunity set new records and sent home major discoveries, along with breathtaking, eerily familiar images of Martian landscapes. In 2012-2013, she became the first explorer to ground-truth the presence of ancient clay minerals on Mars and uncovered the most ancient Noachian terrain ever found on Matijevic Hill at Cape York.

Then, on March 24, 2015, Opportunity roved past 42.2 kilometers (26.2 miles) to finish the first marathon on another planet. Not long after that landmark “run,” the rover drove into Marathon Valley to search for the remnants of a mother lode of clay minerals that orbital data indicated are there.

Now into her tenth mission extension, Opportunity is and heading south/southwest to Cape Byron and the gully that harbors untold Martian secrets.

Driving into Victoria

A simulated Opportunity descends into Victoria Crater by way of an alcove dubbed Duck Bay in July 2007 in this image based on data the rover took with her Pancam. The rover went into the crater to examine older rocks deeper in the crater that held clues to Mars' wet past.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

Since departing Spirit Mound, the first planned science stop on her tenth extended mission, in November, Opportunity has been in the crater rim, slowly scaling the steep slopes of Cape Tribulation heading for the crest. "Driving has been the priority," said Rover Planner Ashley Stroupe, of JPL. But the going continued to be tougher than ever.

Designed to navigate 15-degree slopes, the robot is roving up to the plate sol after sol and on slopes that average around 20-degrees and sometimes more. The steep cliffs, ragged terrain, a blinding summer Sun, and the rim wall to the west that has blocked her communications however have all conspired to slow her pace. But throughout the month of January, the veteran robot field geologist continued her arduous hike. "We're trying to get to our egress point so we can make some good progress down to the gully," said MER Lead Flight Director and Rover Planner Mike Seibert, of JPL.

Opportunity is working her way up to the crest of the rim to that egress point, which will take her onto the flatter terrain of the Meridiani Plains that surround Endeavour’s rim. "We can put it in high gear there and hightail it down to the entrance at the gully at Cape Byron," said Arvidson. "We want to get to the head of gully in enough time to do work before the winter sets in.”

The winter solstice will greet Oppy on November 20, 2017. “But I expect to see the impact of winter on the rover’s solar array energy production starting around August,” said Jennifer Herman, MER Power Team Lead, power subsystem engineer at JPL.

So there’s no immediate rush. Nevertheless, the rover was hiking and driving and climbing so intensely in January that the team members barely had any time to pause and think about their 13 years of roving Mars, much less celebrate their achievement.

It’s an achievement like no other in the history of planetary exploration.

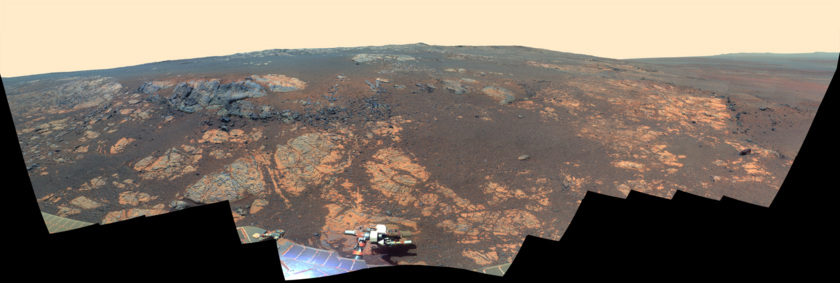

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / Arizona State University

Matijevic Hill

Opportunity took the hundreds of component images for this panorama with her stereo Pancam in late 2012. Named in honor of JPL's Jake Matijevic, one of the creators of Spirit and Opportunity and a Mars rover pioneer, the hill is within the Cape York segment of Endeavour Crater’s western rim. It was here that the robot field geologist became the first to ground-truth the presence of clay minerals on Mars and discover the oldest strata or layer ever found, now know as Matijevic Formation.By all accounts, Opportunity is one incredible robot that has defied everyone’s wildest dreams, an engineering marvel and one of JPL’s best productions. The $1.037 billion invested to date (FY2016) has been paying back and paying it forward in ways that far surpass the cost and in ways that can never be quantified in terms of dollars.

The MER mission’s longevity has had a huge impact – on planetary exploration, on robotics, and on science and technology, among other intangible things. As Earth’s roving ambassadors to Mars, Spirit and Opportunity have inspired, even motivated kids growing up, and endeared people in all parts of the world.

There is something almost human about the rovers. Of course, they were designed to be robot field geologists. Their masts stand about 5 feet tall and they look out on Mars with 20/20 vision much like a human astronaut would. They are mobile and even have an arm to work with. Past that, they’re solar-powered bolstered by an extraordinary lithium ion battery, and are equipped with a few superpowers, like being able to detect minerals from a distance, for one.

"What the rovers do is very much like what you would do if you were there on the surface of Mars yourself,” said Squyres back when. “We got a backpack and we take everything with us." But there was – is – something more.

It wasn’t part of the intended design, but Spirit and Opportunity turned out to be, well, cute, and easy to anthropomorphize, especially for those who grew up on Disney. Is it a coincidence that the Disney-Pixar animated character WALL-E shared their cuteness, their tenacity, and devotion to work?

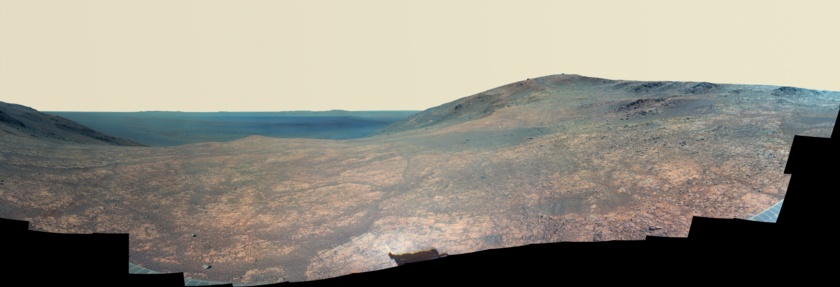

Oppy’s expedition so far

The gold line on this image shows Opportunity's route from the Eagle Crater landing site to her approximate current location. The MER mission has been exploring the western rim of Endeavour Crater since August 2011.The base image for the map is a mosaic of images taken by the Context Camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). Larry Crumpler, of the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, provided the route add-on.NASA /JPL-Caltech / MSSS / NMMNHS

The twin rovers have grown up to be cultural space touchstones and a generation has grown up with real rovers on Mars. At the end of the Martian day though, Spirit and Opportunity couldn’t have achieved all that they have without the dedicated humans guiding her and caring for them every rove of the way.

The keys to the MER mission’s success remain in the hands of the humans and, of course, the natural impulses of Mars. So far Mars has cooperated, even smiled down on the little rover from time to time with gusts of wind to clear her solar arrays, after pummeling her in 2007 during a planet-circling dust storm and nearly taking her out.

Keenly aware of all the challenges they face – known and unknown – the humans have put their hearts, souls, time, and brains into the effort of keeping Opportunity on track and roving ever onward. “There is no way Opportunity could have performed as well as it has if it weren’t for the incredible team of extremely talented scientists and engineers working to get the most out of every day on Mars,” said Abigail Fraeman, who started on the mission in the beginning when she was a junior at Montgomery Blair High School in Silver Spring, Maryland and landed a position as a student astronaut in The Planetary Society’s Red Rover project. She then went on to study under Arvidson for her PhD, and is now MER Deputy Project Scientist at JPL.

“Every single person I’ve met who’s been involved with Opportunity is extremely passionate about what they’re doing,” she continued. “And I think that passion shows through in the consistent high quality work that is put into running, maintaining, and doing science with the MER vehicles over the past 13+ years.”

The MER ops team is a well-oiled machine and for more than a decade has only become more proficient. But the first weeks and months on Mars were crazy. Kind of like the 1960s...a blur in so many respects that if you remember it, you weren’t really there.

Two rovers exploring two different areas of Mars. The scientists and engineers were racing to do as much as possible every single sol, to squeeze as much science they could, and blaze new trails on the job as a “firehose” of data streamed in every day as they juggled in daily press briefings.

Spirit and Opportunity were given an estimated life expectancy, a “warranty,” as Squyres called it, of 90-sols, the length of their primary missions. Within the MER team, there were those however who believed, Mars willing, they could possibly “live” as long as one Earth year, and at least one of the original team engineers suggested the possibility that Opportunity, because of her location, could maybe even make it well beyond one Earth year. But those were projections.

The Pathfinder data indicated the dust would likely blanket the rovers’ solar arrays in a few months time and that would be that. “We thought we would be choked to death and there was nothing to indicate otherwise,” remembered MER Project Scientist Matt Golombek, who served as Pathfinder Project Scientist. Impending doom loomed large.

“We were trying to do 150% every time and that was extremely difficult to do, because often things would happen and we couldn't, so operations were much more intense in the first 90 sols,” he continued. “ And we were pretty much living on Mars time,” meaning their days were 24 hours and 39 minutes and they rose with the Sun on Mars. “We felt almost like there was a sniper trained on Opportunity and Spirit and we didn't know when we were going to get hit,” said Golombek.

They had no way of knowing then the winds and breezes kicked up by Mars would effectively clear the accumulated dust from the rovers’ solar arrays and give them new leases on life. And even though they considered the possibility there was no way to depend on the notorious winds of Mars.

Today the calm and wisdom that comes from experience, more sophisticated software, and new orbiters and cameras, shows. “Our tools are so much more streamlined now and the team has been through it all,” said Golombek. “We know what to do and how to respond in an efficient manner.”

Still, it’s no small task working on the Big Red sol in and sol out. “The process of operating these vehicles is incredibly demanding for this team,” as Squyres put it.

Operating Opportunity requires being able to think about the rover as a whole, a system, while also understanding how the individual components work, from antennas to flash memory to motors. “You need to develop this ability to see the rover at different levels,” said Seibert. “It’s almost equivalent to a biology class where you look at an animal and see muscles and heart and skeleton, and then you zoom in and you see cells in the microscope. That's the same approach we have had to develop in terms of thinking about the rover. It's got macroscopic issues and microscopic issues and we need to understand all of it to keep the rover going."

Opportunity’s longevity has enabled the MER mission to provide a one-of-its-kind apprenticeship program in Mars exploration and it’s one of the best, longest-running planetary exploration training grounds NASA has ever had. The ongoing ops during the last 13 years have allowed JPL to continue to train and maintain the next generation of scientists and engineers in “the niche art of virtually living on Mars through robotic avatars,” as Bell put it.

“Many undergraduate and graduate students who were involved in the early days of the mission are now professors or scientists at NASA centers and are becoming leaders in the planetary science community,” elaborated Fraeman. “If you look around at the engineering team today, you will notice there are many young people who joined the mission well after it was underway and who are now getting first-hand experience running rovers on Mars. On the science team, there are still graduate students who are getting their first taste of planetary science by working with brand new Opportunity data, and many of these students are also involved with tactical operations.”

And, there are several people, like Fraeman, who have been given leadership positions in the mission, where they are learning the responsibilities associated with the kinds of roles needed to make it happen and continue to happen.

Throughout the course of this mission, the rovers and the MER team together have pioneered this distinctive kind of bonded human-robot exploration of Mars. “The rovers are another way that humans project themselves into an alien environment,” as the late Jake Matijevic, one of the original members of the MER team, summed it up years ago.

“The press talk about the rovers aren't human, okay the rovers aren't humans, but there are humans on Mars,” said Golombek. “We are on Mars when we operate Opportunity. There has been a human presence on Mars through Spirit and Opportunity and that's every bit as involving for those of us who operate them as it would be for an astronaut would be if he/she were there. By operating the rover, we're on Mars everyday. And we think as if we are on Mars. We think as if we are a rover in sense.”

That thinking like a rover has served to formed an affection between the humans and the “machine” that is unique in the realm of planetary exploration. It is, arguably, one of the primary reasons Opportunity has roved so long.

For those who have worked on the mission from the start, Opportunity and the MER mission represent a statistically significant part of their career, their lives. “There isn't another mission that has had this kind of intensive operations for this period of time any place,” said Golombek.

The MER ops team has been reduced to about 30 fulltime employees handling multiple responsibilities, with 100 outside scientists, these days. “There are a lot of challenges day-to-day to keep things operating,” noted Seibert. “The rover and Mars keep us from ever getting bored.”

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / Arizona State University

Sacajawea Panorama

Opportunity used her Panoramic Camera (Pancam) in April and May 2016 to take the component images that went into this panorama of Marathon Valley, which the MER team named in honor of Sacajawea, the Lemhi Shoshone woman who helped the Lewis and Clark Expedition achieve its chartered mission objectives exploring the Louisiana Purchase. The view is to the northeast toward the floor of Endeavour Crater. This image was processed in false color, a technique that enables scientists to better discern different geological features. The rover headed down and around Knudsen Ridge on the right and into Bitterroot Valley to begin her 10th mission extension in September 2016.When 2017 dawned at Endeavour, Opportunity was hunkered down on a slope waiting patiently for the holiday celebrations on Earth to end so she could get her commands on how to get out of the sandy predicament she was in.

The plan had been for the rover to enter Willamette Valley, the next valley to the south from Bitterroot, the valley she crossed through in December. The scientists wanted Opportunity to quickly check out some grooves, deeply carved sinuous features there, which are visible in the HiRISE images taken from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). Time and terrain, however, changed that plan.

Just before the December holidays, the rover had encountered a ‘slippery slope’ as she was hiking, and wound up spinning her wheels. "It wouldn't have been a problem if we were driving on level ground," said Seibert. "But we were trying to go up a 20-degree slope and it kind of caused a little bit of sinkage. No major embedding. But that's when we started seeing slip values above 90% and the rover very correctly stopped driving."

That was the end for the Willamette plan. "It's too steep and has too many blocks and too much sand, so we had to put that aside," summed up Arvidson.

Gully or bust

This map shows a portion of Endeavour Crater's western rim that includes Marathon Valley, which Opportunity explored in 2015-2016, and a fluid-carved gully at Cape Byron that is the tour de force attraction for 2017. The width of the area covered is about 800 meters (about a half-mile). North is up. JPL’s Tim Parker, a MER science team member, who originated the Mars Ocean hypothesis, mapped the rover's traverse with a gold line onto an image from the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). Zoom in to see route.NASA / JPL-Caltech / University of Arizona

So Opportunity bumped down that slope, just a short 70-centimeter (2.29-foot) distance to get on more solid ground. Not surprisingly, the rover had scuffed up the surface soil, “a fairly thin deposit maybe 5 to 10 centimeters thick over bedrock," as Arvidson described it.

Then, on December 26th, the rover’s primary communication-relay, the Mars Odyssey orbiter unexpectedly put itself into safe mode. That prevented Opportunity from sending home any of her research or pictures, because working in persistent RAM mode means the rover cannot save data overnight.

That left Opportunity and the team no choice but to sit tight. The Odyssey ops team diagnosed the cause and restored the spacecraft, which has been in service at Mars since October 2001, to full operations. On December 30, 2016, the two – rover and orbiter – reconnected.

With the holidays wrapped as quickly as the presents most people received, Opportunity bumped 2 meters (6.56 feet) on Sol 4601 (January 2, 2017) to get a good look at the mess she’d made and saw some fairly interesting “unconsolidated material,” as Arvidson described it. This was a chance for the robot to conduct some long overdue in-situ or contact research with her chemical analyzing Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS) and close-up camera, the Microscopic Imager (MI). “We realized we hadn't done any observations of the surface since October [2016].”

Opportunity spent the rest of the first week of the New Year checking out two targets in the mix. Continuing the naming theme of Lewis and Clark sites, the team christened the targets Sibley and Missouri City. In addition, the rover also conducted the usual remote sensing, taking images with her Pancam and Navigation Camera (Navcam).

On Sol 4603 (January 4, 2017), Opportunity conducted the now standard science investigation on Sibley, first taking close-up pictures with her MI for a mosaic of the surface, and then determining its chemical makeup with the APXS. The robot then turned to Missouri City, the selected offset surface target, and completed the MI mosaic and APXS work on Sol 4605 (January 6, 2017). In the end, the stuff in the scuff turned out to be soil and breccia rock fragments typical of what the rover and the scientists had been finding in and around Endeavour.

"Since then, we've been focused on getting out of Cape Tribulation,” said Arvidson. “It's still pretty tough, because the downlinks [through Odyssey] are variable. We can't see much to the west, because the rim occludes the horizon.” The comm signals won’t go through the rim of course. That means the robot can’t send data home. Since she is working in RAM, she can’t really work on science on such sols. But this too shall pass.

A slippery slope

Opportunity used her Pancam to take this true color image of the wheel track she left on a slippery slope in late December 2016. Unable to climb up the slope because of the steepness and the ‘slippery’ soils, she backed down and then hunkered down until the New Year rang in.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

It is summer at Endeavour now and even though the tilt of the rover is often away from the Sun as she climbs up the slopes of Cape Tribulation, the rover began the New Year with decent power and 43,742 meters (43.74 kilometers (27.17 miles) on her odometer. With a solar array dust factor of 0.683, she was producing around 520 watt-hours under still hazy skies, Tau registering around 0.752. All things considered, those stats are really pretty good.

Opportunity pressed on dutifully, taking a new path that diverted from original extended mission route. It would send the robot up even more rugged, steeper slopes, around to the west of Beacon Rock, a large rock mound clearly visible in the overhead HiRISE images. "We ended up diverting onto some firmer, but steeper terrain," said Stroupe. "We have been driving in small chunks, moving up these steep slopes.”

The rover hiked 12.6 meters (about 41.34 feet) to the northeast on Sol 4607 (January 8, 2017). Then on Sol 4609 (January 10, 2017), Opportunity headed approximately west in a two-segment drive, totaling more than 25 meters (about 82.02 feet).

"Instead of cutting downslope of Beacon Rock and then up through the Willamette Valley area with those grooves, we actually had to backtrack a bit to the north,” said Seibert.

When Opportunity attempted to drive up another steep slope on Sol 4611 (January 12, 2017), her flight software stopped the drive after just 1.25 meters (4.10 feet). It sensed that the wheels were drawing too much current, an indicator of embedding. In the pictures the rover sent home however, the rover ops team could see the ground had crumbled under the driving shear forces of the rover's wheels and caused causing the wheels to slip. The RPs huddled to consider the rover’s next move.

The 4611 drive was part of a three-sol plan that included a late-night Ultra High Frequency (UHF) relay pass with NASA’s newest orbiter, MAVEN. Since the MAVEN pass required Opportunity to stay up really late, to near midnight, the always willing, ever-capable robot took a nighttime image of Deimos and MAVEN successfully downlinked it to Earth.

As if scaling treacherous slopes wasn’t difficult enough, Odyssey’s low-elevation flight pass was blocked by the rim to the west the next sol, so Opportunity was forced to take break. The summer Sun continued to present challenges as well, sometimes shining a little too brightly on the rover’s workspace.

"Since we don't have flash, we have to stay awake now until we downlink the data, so the best thing is to wake up Opportunity shortly before the pass, do the drive and send the data down," said Stroupe. "The problem is, late in the afternoon, when the rover is looking west, she’s looking right into the Sun and we don't get good quality data. That pushes us to try and do the drive earlier in the day, and we stay up longer."

Sibley and Missouri City

In late December 2016, Opportunity struggled to climb upslope and wound up scuffing up the terrain. In early January, the rover checked out a couple of targets in the mix but found the team found the soil and breccia rock fragments typical of what the rover and the scientists had been finding in and around Endeavour Crater.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

On Sol 4614 (January 15, 2017), Opportunity backed downslope about a half-meter, then turned to travel more cross slope toward exposed rock outcrop the ops team took to calling ‘the yellow brick road.’ The rover put 14.67 meters (48.13 feet) in the rear view mirror with little slip. As usual, she took a bunch of pictures with her Navcam and Pancam to support both driving and science, and then she used her APXS to take an atmospheric argon measurement after the drive for the mission long study on Mars’ atmosphere.

"We're trying to get through this area that looks like darker material on the HiRISE images, which seems to be softer, more soil covered regions,” said Seibert. It's like driving in snow here on Earth, he said. “Occasionally you drive into something where you sink in a little bit and hope you don't go too far so that you can back right out and get onto good traction. That's what we've been doing.”

The ‘yellow brick road’ runs through it though and it made the drives a little easier. “It’s a bunch of exposed outcrop so we know we would have good traction and once we got back onto that material, driving was great,” said Seibert. “We saw low slip and we were able to climb right up these hills and make progress to the west.”

The rover putting a good 25.61 meters (84.02 feet) behind her on Sol 4618 (January 19, 2017). This yellow brick road in no Autobahn though. Two sols later, 4620 (January 21, 2017), the rover only managed to drive 14.54 meters (47.70 feet) to the southwest. “We were getting off onto softer soil again, and saw a little higher slip of around 30 percent at the beginning. But once we got back on outcrop it dropped to less than 10 percent,” said Seibert.

“It's a big change in terrain types when you're driving on slopes, it makes a difference,” he said. “Nothing's really hindering this rover. It's just learning what the terrain is like under the wheels and getting used to operating Opportunity on different terrain types and steep slopes and it can vary and change pretty quickly.”

On Sol 4622 (January 23, 2017), Opportunity drove just 10.58 meters (34.71 feet) southwest, “as far as we were able to get on that sol,” said Seibert. But every meter counts and the rover would make up for it the next day, her big day. When Oppy shut down, she was still an “adolescent.” When she woke the next sol, she was officially declared a teenager and was already acting like teenagers on Earth, as NASA-JPL put it in a special 13th anniversary tribute video.

Opportunity celebrated her 13th birthday on Sol 4623 (January 24, 2017) doing what she loves to do, driving. And she climbed up hill, west/southwest, she logged 27.13 meters (89.009) and finally put Beacon Rock in the rear view mirror. "Getting around it was a chore," said Arvidson. "Because of the steep slopes and the nature of the terrain we just can't do long drives right now, so it took us a while to get up and around to the north."

Meanwhile, on Earth, the following night some of the MER ops team got together at a local restaurant in Pasadena California. "We had a nice happy hour and several of the science teams members were in town for a Curiosity science team meeting, so we had a nice low-key get-together with a core group of people,” said Stroupe.

Shooting Deimos

Opportunity took this image of one of Mars’ two moons, Deimos, which closer up looks like a lumpy rock that looks more like an asteroid than most other moons in our solar system. It was discovered the focused search for Martian moons by American astronomer Asaph Hall on Aug.12, 1877. Six days later, Hall identified the other Martian moon, Phobos. Mars is the only terrestrial planet to host multiple moons.NASA / JPL-Caltech

The next morning, it was back to work on Mars. Opportunity's location in the rim continued to constrain the pace. Since the Sun had too often been annoyingly in her face when the rover finished her climbs, the ops team deployed a technique they first used back at Endurance and then Victoria Crater. "We set the time of day for when we absolutely need the rover to stop driving and take take the post-drive images, we sequence a bunch of drive commands, and then let the rover drives until it runs out of time,” explained Seibert.

So far so good. As January wound down, Opportunity revved up. The robot field geologist climbed up slope three sols in a row, logging 23.24 meters (76.24 feet) to the west on Sol 4624 (January 25, 2017). Then, the following sol, 4625, the rover turned left to head south and put another 18.91 meters (62.04 feet) on her odometer to the south, only stopping because she ran out of time and had to take post drive images before the sunlight smacked her in the face.

On Sol 4626 (January 27, 2017), the robot woke up and drove again for 11.72 meters (38.45 feet). Before and after driving, the rover took images as always and worked in an atmospheric argon measurement. The next sol, 4627 (January 28, 2017), Opportunity did an IDD salute and prepared to do some groundwork on a target the team nicknamed Fort Thompson on Sol 4629 (January 30, 2017). “It was a target of opportunity,” said Arvidson. “We wanted rock but where the rover stopped was mainly soil, so we did MI and APXS on the best spot to get rock but it was mainly soil. It turned out to be similar to other soils.”

Opportunity continued to push south, driving out of January on Sol 4630 (January 31, 2017) with a 21.79-meter (71.49-foot) drive bring her total odometry to 43,940 meters (43.94 kilometers, 27.03 miles). The rover stopped a little short of the commanded distance, because the visual odometry algorithm had difficulty resolving progress from near-featureless images of the ground.

The geographical constraints kept a kind of lid on the rover’s energy. Opportunity’s power levels fluctuated between 463 and 520 watt-hours, with the final stats as of Sol 4629 being 469 watt-hours of power and a dust factor 0.674, with Tau being recorded at 0.746. While she’s producing less power than usual during this summer, it’s enough to allow the rover to keep driving and forging ahead.

"The power is okay. But it's been highly variable," said Stroupe. "With the diversion that we had to take, we are actually getting less favorable tilts than we were for a little while, but we're still okay, although the drives are sometimes a little bit constrained."

For the science team, the greater issues in January were the facts that Opportunity has to work in RAM mode, the afternoon Sun, and the lost Odyssey passes. The scientists rely on getting enough good Navcam, Hazcam, and Pancam images of the surroundings to plot the rover’s next drive. “That’s what we need to have a good mesh of images to understand exactly how to get through this difficult terrain.”

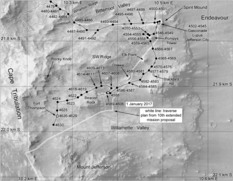

Oppy’s recent roves

This graphic charts Opportunity's recent rovings, from Sol 4479 (Aug. 30, 2016), about fives sols or Martian days before the rover exited Marathon Valley and headed for Spirit Mound, to a recent drive on Sol 4630 (Jan. 31, 2017) that is the rover’s exit from Cape Tribulation. The annotated map is courtesy Phil Stooke, an associate professor at the University of Western Ontario, Canada, author of The International Atlas of Mars Exploration Vol. 2, Spirit to Curiosity: 2004 to 2014 (Cambridge University Press, 2016). The base image was taken by the HiRISE camera onboard MRO.NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / P. Stooke

As always, the rover and the team carried on, just like they have for 13 years and counting. Even as experienced as this world-class rover team is though, it’s difficult for them under these circumstances now to predict exactly how quickly Opportunity can make progress and get out of the rim.

"It's been difficult to do any real strategic planning because we just don't know," said Stroupe. “Some days we come in and were lucky. We've landed on the high point and can see really far, and have good terrain in front of us. Other days we come in and there's a hole in the mesh, because of a little rise that we can't see past, so we end up having to do really short drives.”

Those short drives add up however and by month's end, Opportunity chalked up 209.49 meters (687.30 feet), every meter of which almost was hard earned. It’s clear to see the rover made significant progress toward her “exit” at the crest when you look at the overhead maps (pictured in this Update), charted by Phil Stooke, author of author of The International Atlas of Mars Exploration Vol. 2, Spirit to Curiosity: 2004 to 2014 (Cambridge University Press, 2016) and an associate professor at the University of Western Ontario, Canada.

In comings sols, the plan will likely include one more science stop to take some APXS analysis on some bedrock. “We haven't done that for a few months, since October,” said Arvidson. “Other than that it's getting up and out of Cape Tribulation and onto the Meridiani Plains.”

The MER scientists are as excited as they have ever been on this mission – save perhaps for the landing days all those years ago – and they’re getting more and more anxious to get to the gully. Opportunity seems excited too. At least she’s ready to rove. No surprise there. "It's amazing how well it's performing for being a 13-year-old vehicle on Mars," said Seibert.

Despite her broken shoulder and front right front wheel, the loss of a couple of mineral detectors, and her flash or long-term memory, the future still looks bright for this vivacious veteran. The gully is now under a kilometer (0.62 of a mile) away but first Opportunity has to get to the crest and onto flatter, terrain where this rover can make serious tracks.

It’ll still be a few weeks of hard driving and climbing though and the MER ops team will have the rover’s back every rove of the way. "We're still on really steep slopes, but were moving along at a slow, but steady pace," said Stroupe.

As much work as tending to a rover on Mars has been all these sols and months and years, this team remains as enthused and energized as ever. “It’s still a lot of fun,” said Arvidson. “And we're still making discoveries practically every week.”

The rewards of more than a decade’s worth of dedicated work, of the long hours, sleepless nights, and nail-biting moments come in different ways to different people. “I continue to be thrilled when I walk into a coffee shop and see Pancam mosaics on people's laptop backgrounds, or when I see a poster on a wall in a school that showcases images from Spirit and Opportunity,” said Bell. “Or maybe especially (in my own geeky way) when I see a new research paper published that has gone back and used some of the early data from the missions to pull just a bit more science out of the images and other measurements. Sweet!”

Others look at Mars in the night sky and are ‘transported.’ "I have a feel for what time of sol it is on Mars, and when I look up at this dim red dot in the night sky, I think: 'Opportunity is driving now,’” said Seibert. “It's so much more than, 'Oh there's a planet.' It's knowing the rover is there and what’s happening right then."

Earth from Mars

In January, JPL released this image of Earth and its moon combines two separate exposures taken on Nov. 20, 2016, by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. It’s not exactly Opportunity’s view, but it is a cool image.NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA

Beyond demonstrating the kind of teamwork that makes magic happen and impossible things possible, the MER crew – and anyone and everyone who has ever worked this mission – is grateful. "MER is something that I will never take it for granted," offered Stroupe. "It will always feel incredibly special, incredibly unique. Every day I still feel lucky I get to do this.”

“I remain thankful and full of awe that we – not just the rover teams but all of us – have been able to vicariously experience and try to understand the beauty and mystery that is Mars every day, for more than 2200 sols in Gusev Crater, and more than 4600 sols so far in Meridiani Planum,” pondered Bell. “What an adventure!”

Back in the early days, people would bet, just for fun of course, on how long the MERs would last. About a year and a half into the mission those still willing to wager were now hedging their bets with a far-out-there number of 5 years.

You don't hear about bets anymore and no one talks about ‘the end’, even though with every passing sol, month, and year, those on the MER team and all those who have loyally following the twin rovers are keenly aware of reality.

As Squyres reminded years ago: "These things are not immortal. They will not go on forever." His greatest hope is that Opportunity roves until Mars takes her life. "There are any number of ways this mission can end, but the one way I do not want it to end is because we screwed up."

That hope has become the ethos of everyone working on the project, including the younger guard. "We have folks now who were in grade school when we landed and who are now incredibly dedicated to the rover and dedicated to learning everything they can and coming up with ways to keep us operating,” said Seibert. “It goes beyond just keeping the rover ‘alive.’ We're working on figuring out how to maximize the drive distance, the science return, and finding new ways of looking at stuff,” he said.

There will never be another MER rover. “We're operating something that can never be replaced. It cannot be a ground site issue,” Seibert said. “It cannot be a flight team screw up. Opportunity is a priceless scientific asset on Mars. We know that. And everybody wants to keep pushing forward. We have a team that won't give up.”

Now, as Opportunity begins her 14th year on Mars, she is in good human hands. “We who operate her look forward, said Nelson, to the new discoveries, new vistas and new milestones she will surely achieve.”

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

Spirit on Husband Hill

This special effects (fx) image of Spirit on the flank of Husband Hill, named for Rick Husband, commander of Space Shuttle Columbia's final, tragic mission, was produced using JPL's "Virtual Presence in Space" technology. The size of the rover in the image is approximately correct and was based on the size of the rover tracks in the mosaic.Spirit Remains Silent at Troy

Stuck in the sandy edge of a shallow hidden crater along one side of Home Plate, Spirit phoned home on Sol 2210 (March 22, 2010) just before she went into a planned hibernation.

The robot that came to known as the-little-rover-that-could had worked for more than six Earth years and drove 7,730.50 meters (4.80 miles) in some of the harshest Martian terrain the mission will ever encounter. She was the first rover to climb a mountain, the first robot to take pictures of dust devils on the surface of Mars, and the first to find evidence for near-neutral water on Mars. In those 6+ years, Spirit literally defined MER mettle.

For the next year, NASA-JPL radiated more than 1,300 commands to Spirit as part of the recovery effort to elicit a response, any response. Hearing nothing in all that time, NASA officially concluded recovery efforts on May 25, 2011. The remaining, pre-sequenced ultra-high frequency (UHF) relay passes scheduled with the Odyssey orbiter completed June 8, 2011. No one has heard from Spirit since.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth