A.J.S. Rayl • Jan 31, 2012

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Celebrates 8, Keeps on Rockin' into Year 9

As Opportunity worked away on its winter science campaign, the Mars Exploration Rover mission quietly completed its eighth Earth year of exploring the surface of the Red Planet last week, and is now roving on into Year 9 of its 90-day mission.

"It's astonishing to me that we're still going after eight years,” said Steve Squyres, the MER principal investigator, of Cornell University, during an interview earlier today. “Every day at this point is a wonderful gift."

By any account, the MER mission’s longevity has defied all odds and then some. There are now elementary school children who have grown up with rovers on Mars, and generations of students during the last decade that have been inspired by the twin robot stars to not only take an interest in science but to dream big and to believe in themselves. Beyond that, the global embrace with which Spirit and Opportunity were enveloped from the moments they landed on January 3 and January 24, 2004 has since transformed the golf-cart-sized rovers into America’s most recognized and beloved goodwill ambassadors.

Opportunity, in its eight years of roving Meridiani Planum, has made textbook changing discoveries beginning with finding the first in-situ mineralogical evidence that Mars had liquid water, fulfilling its main science objective during its prime mission in 2004. As the rover moved on, it became the first to take pictures of its own jettisoned heat shield and the first to investigate a meteorite on Mars. And, as the robot field geologist went crater hopping across the rippled plains, she became the first rover to be snared by – and successfully escape – a Martian sand dune, the first to survive a life-threatening global dust storm in 2007, and the first to drive into a Martian crater.

On completing a two-year investigation of Victoria Crater, which at 750-meters (0.46 mile) diameter was the largest crater investigated to that time, the rover headed out on a 7-mile journey to reach a really, really big hole in the ground, a crater nearly 22 kilometers (14 miles) in diameter that the team christened Endeavor. Despite the rover’s resilience and seeming desire to rove and rove, no one really knew if it was possible. But after nearly three Earth years of endless driving, much of it backwards because of a problematic “hot” right front wheel, Opportunity pulled up to the rim of Endeavour in August 2011, at a place named in honor of her twin, Spirit Point, a destination considered an impossible dream in the beginning. The mission continues now at Cape York.

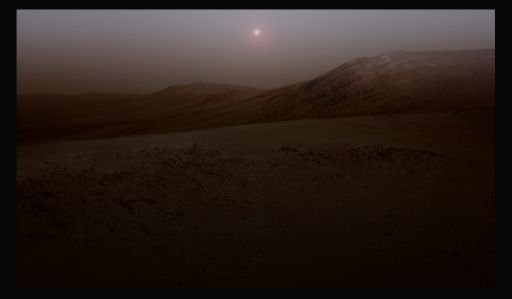

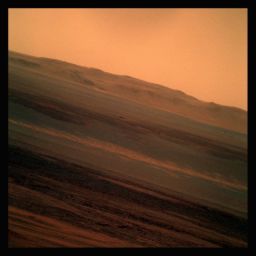

A winter wonderland

A winter wonderlandOpportunity looked out over her own shadow and took the pictures of Endeavour Crater that went into this image with her panoramic camera (Pancam. It was just before sunset, local Mars time, on Jan. 24, 2010, the MER mission's 8th anniversary of exploring Meridiani Planum, Mars. Damien Bouic/Ant103 of UnmannedSpaceflight.com assembled the 20 some black and white pictures, processed them and rendered this striking image.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / D. Bouic

Along the way, Opportunity put more than 34 kilometers (some 21 miles) on her odometer and established a long list of rover driving records. With one exception, this robot field geologist has beaten every robot survival and distance driving record, including those set by the astronaut pilots of the Apollo Moon buggies. The only record left for this MER to best is the driving distance record of 37 kilometers held by Lunokhod-2, a robotic lunar rover belonging to the former Soviet Union. [Ed. Note: Although Lunokhod-2, “Moonwalker-2” in Russian, roved for 37 kilometers around Le Monnier Crater in 1973, its mission only lasted a few months, from January 15-June 4, 1973 – and the Moon is a much less harsh mistress than Mars.]

Even though NASA, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), which serves at the rover mission control, and the country have a lot to shout about with the MERs, the rovers have already been honored and acknowledged with more awards and accolades than George Clooney (and by most reckonings are just as “cute”). And so when January 24th arrived last Tuesday, marking eight years to the day since Opportunity bounced down on Mars to score "a 300-million-mile hole-in-one," there was little fanfare down on Earth, and no banner headlines in the global media.

With the Martian winter gripping the Meridiani Planum region, the robot field geologist and its team focused on working not celebrating, to get as much work done as possible before the depth of winter arrives in the southern hemisphere of the Red Planet where the rover is generally located. "We just kind of keep going," said Squyres. "We’re still busy doing operations. The thing about flight operations is you’ve got to do it today.”

Up on Mars, then, it’s been business as usual this past month for the heralded rover and her team. Since arriving at Cape York on the rim of Endeavour Crater, significantly older and different terrain than the plains over which Opportunity spent more than 7.5 years traversing, the mission has entered a new phase, effectively starting all over again. “We're working and we’ve been making good progress,” reported Ray Arvidson, deputy principal investigator, of Washington University St. Louis (WUSTL), who is overseeing the winter science campaign.

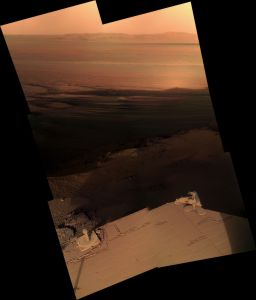

A bird's eye view

A bird's eye viewOpportunity used her Pancam to take the images that were then combined into this mosaic view of the rover herself. The downward-looking view omits the mast on which the camera is mounted. Heading into its fifth Martian winter, the rover's solar panels are dustier than ever, requiring the team to choose an area of high northward tilt to increase power. This mosaic was taken days before settling into the winter haven position, which is informally called Greeley Haven, in memory of planetary geologist Ronald Greeley (1939-2011). Greeley Haven sits near the northern edge of Cape York, on the rim of 22-kilometer-wide (14-mile-wide) Endeavour Crater. The images were taken through the camera's 601nanometer, 535nm and 482nm filters during Sols 2811 and 2814 (Dec. 20 and 24, 2011).Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / Image mosaicking: Jim Bell, Jonathan Joseph; Calibration and color rendering: CCC and the Pancam team

During the last four weeks Opportunity turned on its spectrometers to study the content of the local bedrock, tuned in to radio signals in an experiment that could further inform scientists about Mars' core, and "dropped" into the data pipeline to Earth a significant chunk of the thousands of images that will make up the next 360-degree, take-your-breath away panorama.

Although the rover has managed to put in a good sol's work up just about every sol or Martian day throughout January, the pace is beginning to slow as winter progress toward the winter solstice at the end of March. "We're beginning to feel the pinch of energy now," said Arvidson.

"As expected, we are seeing decreasing power levels and it's going to continue for the next few months," confirmed John Callas, MER project manager at JPL.

The "pinch,” as Mars would have it, is coming just as the robot field geologist has begun one of the most fascinating, long awaited experiments in the mission – investigating the planet’s core through radio Doppler tracking research. The MER rover model was never really designed to do this kind of research since it requires the robot to be stationary and rovers are designed to – well, rove. But this work promises to break new scientific research ground and, once again, rewrite planetary science textbooks, perhaps by ultimately informing scientists with certainty that Mars' core is liquid. And since the rover is parked for winter anyway…

"It's been a long time coming," physicist-technologist William M. (Bill) Folkner, a principal engineer at JPL and the MER participating scientist who is heading the experiment, said during a recent interview. From the looks of data collected this month, the waiting may well turn out to be the hardest part. Actually, the data are "a little more powerful" than anticipated, Folkner said, “because we're closer to Mars than we were during the Pathfinder mission in 1997.”

From its parked position, Opportunity is now regularly tracking the dynamics of the Mars’ spin axis by using its high gain antenna (HGA) and establishing a 2-way radio link with the Deep Space Network (DSN) radio telescopes. "When the rover sends data directly to Earth on its HGA, if it's also locked to an uplink signal from the DSN, we can measure the roundtrip Doppler shifts," explained Folkner.

Typically, the rover will point its HGA and track for 30 minutes in any given session. Scientists will look for the Doppler shift in the signal data the rover sends home. "If the rover is stationary, then we can use the daily or weekly estimates of the longitude and spin radius (distance from Opportunity to the Mars spin axis) to determine the direction that the Mars spin axis points in inertial space – which quasar does it point to, or which star does it point to? The spin axis direction changes slowly with time due to precession."

Precession refers, by definition, to changes in an astronomical body's rotational or orbital parameters. Generally, people are familiar with Earth's precession in relationship to its movement through the different constellations of the zodiac. The Earth's axis completes one full cycle of precession approximately every 26,000 years. "Over 26,000 years where the Sun rises at the vernal equinox (March 21st) varies across the 12 signs of the zodiac and so that's the precession," as Folkner explained it in a nutshell. By improving or getting a better handle on the precession of Mars, scientists can deduce more about the planet's core, including its make-up, how big it is, and how dense it is relative to the lithosphere or the mantle. "Long-term change in the spin direction could tell us about the diameter and density of the planet's core. Short-period changes could tell us whether the core is liquid or solid," he summed up.

Collected over a number of months, this data will enable planetary scientists to back-calculate the planet’s interior density, for example, as a function of depth needed to produce the spin axis dynamics.

Opportunity has only just begun the radio Doppler tracking, and Folkner has determined that he needs to modify his analysis software. Nevertheless, after running the data gathered just during the first week of January, he believes that after analyzing the rest of the month's bounty, he will be able to improve the current numbers on Mars' precession "by a factor of two." That improvement, he suggested, "is good enough to rule out about half of the interior models of Mars we currently think is viable."

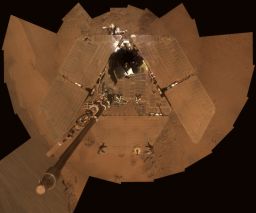

Opportunity on Endeavour's rim (detail)

Opportunity on Endeavour's rim (detail)This HiRISE image, taken on September 10, 2011, shows Opportunity sitting atop some light-toned outcrops on the rim of Endeavour Crater, near a smaller crater dubbed Odyssey. The rover travelled nearly three years from Victoria Crater to reach the rim of Endeavour, which boasts rocks that are older than the rocks of Meridiani Planum, which the rover has been exploring since 2004; therefore may teach scientists something about an even more ancient era in Martian history.

Credit: NASA / JPL / UA

But there’s more to be learned from the radio science research. Mars, like the Earth, features distinctive wobbles too, and those wobbles can add significantly to our knowledge about planet cores. Earth's wobble is "somewhat stabilized by the Moon,” but “Mars has a much bigger wobble that shakes every half Martian year and every Martian year,” Folkner pointed out. [Ed. Note: A Martian year is 686.98 Earth days or 1.88 Earth years, approximately equivalent to two Earth years.]

While most planetary scientists these days generally agree Mars' core is liquid, to unequivocally confirm that and to actually measure a wobble Folkner needs more time, 12 Earth months’ worth of time in a perfect world, at least according to his first simulation. And, he needs the rover to stay still or move very, very little. But rovers – especially Opportunity – just want to rove, and “it costs energy to send a radio signal directly to Earth," Folkner noted, adding that he plans "another simulation" in February to see how much he can pare down that hefty request for this rover’s time and energy.

“This is going to be another significant achievement for the MER project once it's done,” said Squyres.

Throughout the month, Opportunity has been pointing and clicking her panoramic camera (Pancam) everywhere, taking hundreds of pictures of her surroundings for the 360-degree Greeley Panorama, named for and dedicated to the beloved planetary scientist and MER science team member Ron Greeley, the Regents Professor in the School of Earth & Space Exploration at Arizona State University (ASU), and Director of the NASA Regional Planetary Image Facility. Greeley passed away last October.

"Two tiers of the Greeley Panorama are down and being calibrated and processed," informed Planetary Society President Jim Bell, the Pancam lead, ASU. "We are hoping to fill in at least more of the foreground in front of the rover, but the details of how much more we'll be able to cover beyond that are to be determined, because it will depend on whether we decide to scootch the rover to a different position on the outcrop. So, stay tuned."

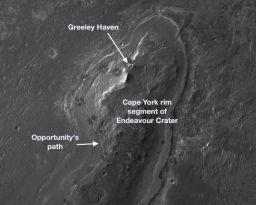

Endeavour west rim map

Endeavour west rim mapThis geological map -- based on observations by the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter -- indicates some of the information gained from orbital observations of Endeavour Crater, the long-term destination for Opportunity since September 2008. Endeavour is about 22 kilometers (14 miles) in diameter. As indicated by the scale bar of one kilometer (0.6 mile), this map covers only a small portion of the crater's western rim. A discontinuous ridge runs north-south, exposing basalt (coded blue) and clay minerals (coded green) believed to be from a time in Martian history before the deposition of sulfates on the portions of the Meridiani Plains region that the rover has seen during its first seven years on Mars. The rover team plans to begin Opportunity's exploration of the Endeavour rim near Cape York, which is about 6.5 kilometers (4 miles) from the rover's location in mid-December 2010. Cape York is nearly surrounded by exposures of hydrated bedrock. From there, the planned exploration route goes south along the rim fragment Solander Point, to Cape Tribulation, where clay minerals have been detected.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / JHU-APL

Opportunity also spent quality time investigating the composition of the local bedrock, effectively the northern end of Shoemaker Ridge that distinguishes Cape York. After taking a good long look at the bedrock target the team calls Amboy with her alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS), the rover put her other spectrometer, the Mössbauer, on the same target to try and glean the amount of iron it may be harboring.

Just as the winter science campaign kicks into high gear, however, winter is stealing precious energy. The aphelion – the point in its orbit when Mars is furthest from the Sun (1.66598 AU, 249.2 million kilometers, 154.8 million miles) – is coming up February 15th, noted Arvidson, and then the winter solstice in the southern hemisphere of Mars occurs at the end of March.

"So the energy is down, and it's already taking a while to actually figure out what we can actually do on any given sol. We're having to make trade-offs,” Arvidson said. “How much radio science we can get in will become dicier and dicier as we move through February, but it is the number one science priority, and really the most important thing we can do this winter.” The radio science experiment could represent, he added, “a major contribution” to understanding of geophysics of Mars.

Turns out, aphelion – not the winter solstice – will be the coldest part of this Martian winter, the fifth for Opportunity, said Bill Nelson, chief of the rover engineering team at JPL, citing a recent analysis. “Once we pass the middle of next month we should see things slowly begin to warm up,” he said.

Eight years and counting, Opportunity’s outlook remains bright. Winter chills aside, the rover is healthy and there are no real concerns at the moment. "The rover is doing just fine," said Nelson. "She has an approximate 15-degree northerly tilt, which is almost as good as she could possibly get … and we are more or less where we were predicting. The dust factor is a little worse than we thought it would be. The Tau is a little higher than we thought it would be, both of which are not good. But energy is pretty much right as predicted,” he said. One reason is that Opportunity has been tapping into her battery less, so it's state of charge has been higher than predicted. “Because of that, we generated a bit more power, so we've managed to hold more or less on predict,” explained Nelson.

In any case, given the caveat that this is Mars and anything can happen anytime, Opportunity is certainly not facing the life-or-death scenarios that her twin faced every winter. Located further south of the equator, Spirit would not have survived its first three winters without perching on northern slopes and hunkering down to save energy. And as it turned out, it was the last Martian winter that ended Spirit’s mission.

At Endeavour Crater, Opportunity, though parked, will likely be able to take care of business and pack in the science investigations as planned throughout the season, despite her extra dusty solar arrays.

Although Spirit stopped roving last year, Opportunity has carried on. In many ways, it almost seems as if Opportunity has been striving to make up for Spirit’s loss or perhaps distract the team with new wonders. And as for the new wonders, the rover’s done an admirable job, by taking the mission into a whole new landscape at the edge of Endeavour, a place that speaks of a more ancient time, when Mars was wetter and warmer and more like Earth.

As January turns to February, 2012 is looking good. "Everything is going according to plan and if the projections hold true we will be able to do nominal science throughout the winter," added Arvidson. "We just have to be more and more careful about calculating the energy and making sure we're staying within reasonable constraints."

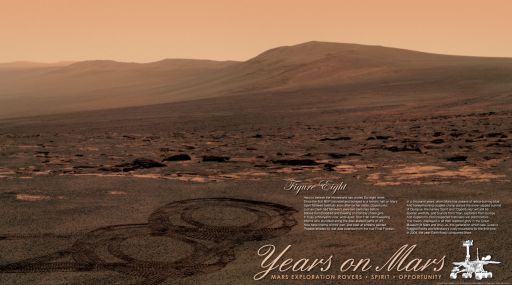

Figure 8

Figure 8On January 24, 2012, the Mars Exploration Rover mission celebrated 8 years of roving Mars, very quietly, as Opportunity worked through the anniversary and into Year 9. MER poet Stuart Atkinson and artist Glen Nagle, both of UnmannedSpaceflight.com, the team that produces the MER "poemsters" that have accompanied various MER Updates over the years, weren't about to let the anniversary go unnoticed. The MER Update is proud to be able to present their latest production, Figure Eight, here.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / Words: S. Atkinson; Poster production and imaging: G. Nagle

"The health of the vehicle is good, knock wood," Squyres summed up, as he knocked the wood on his desk. "We haven't had anything break for a while. Everything is working as it has been for some time, and, yeah, we have a healthy, happy vehicle. I wish we had cleaner solar arrays. Other than that, we're thrilled."

There's every reason to believe Opportunity will cruise through winter and rove on to the south along Endeavour’s rim to hunt for smectite, the clay minerals that are phyllosilicates and groundtruthing evidence of past life-friendly water, water as we know it – a find that would be a crowning achievement for the MER mission.

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

Opportunity rang in the New Year on her 2822th day on Mars by launching into her winter science campaign from her parked position on the north end of Cape York on the rim of Endeavour Crater.

Simulation of Opportunity at Greeley Haven

Simulation of Opportunity at Greeley HavenMichael Howard, the creator of the heralded Midnight Mars Browser software, put together this simulated image of Opportunity. It shows the rover in her (approximate) winter parked position at Greeley Haven, which is located on the northern end of Cape York.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / M. Howard

The rover hiked onto her winter haven last month, with 34.36 kilometers (21.35 miles) on her odometer. Perched on a bedrock slope atop the northern end of Shoemaker Ridge at about 15 degrees, the rover angled her solar arrays toward the Sun to take in as much possible sunlight for energy production during winter. This will be “home” for the next several months.

As 2011 turned to 2012, Opportunity was producing about 287 watt-hours of power, a little less than one-third full power capability. The skies over Endeavour Crater remained annoying dusty, with the rover recording an atmospheric opacity or Tau of 0.735, while her solar array dust factor continued to hover around 0.481.

After completing an extensive observation of the bedrock target known as Amboy, Opportunity changed instruments on Earth’s New Year’s Day, placing the Mössbauer spectrometer on Amboy for an extended integration on Sol 2822 (January 1, 2012). That same sol, the rover carried out the planned series of special X-band passes initiating the radio science or Doppler tracking experiment to measure the precession and nutation or the periodic variation in the inclination of the axis of Mars. It was a good day on Mars.

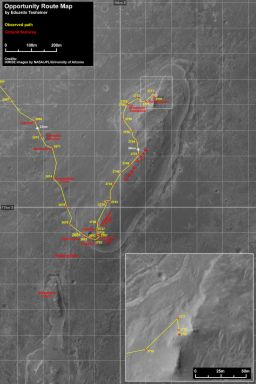

Opportunity route map

Opportunity route mapThis Opportunity route map was porduced by Eduardo Tesheiner, of UnmannedSpaceflight.com, and created from images taken by cameras onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. It shows the rover's travel up to its Sol 2790 (Nov. 29, 2011) and its approximate current location at Cape York. The rover officially reached the rim of Endeavour Crater on Aug. 9, 2011 and is hunkered down now in a parked position for her fifth Martian winter.Credit: Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / MSSS / E. Tesheiner

Throughout the rest of the month, Opportunity focused on the three primes directives of the winter science campaign, but also snuck in a few ancillary assignments.

During the second week of January got underway, the rover used her the microscopic imager (MI) to take more close-up pictures of Amboy on Sol 2829 (January 8, 2012), and then placed her Mössbauer spectrometer down once again on Amboy to try and determine its iron content. Opportunity also continued conducting regular radio Doppler X-band tracking measurements, and collected color panoramic camera (Pancam) images that will go into the 360-degree Greeley Panorama.

After taking some pictures to assess things, Opportunity slightly repositioned the Mössbauer on Sol 2831 (January 10, 2012). The instrument had been “acting up,” as Nelson put it, and exhibiting temperature-related anomalous behavior.

Two sols later, on 2833 (January 12, 2012), the rover performed a tool change to place her alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) on Amboy.

With multi-sol APXS integration ongoing, the rover team took advantage of several opportunities to have the rover perform some Mössbauer temperature diagnostics to try and establish the best temperature range of operation for the iron-detecting instrument. Like everything else on the rover, the Mössbauer is, aging. Its radioactive source has been steadily fading, and it now takes weeks of integration or sitting on a target to get useable data. “The instrument is now in its 12th or 13th half-life, so it's getting to the point where it's not going to be useable much longer,” said Nelson. “Certainly, this is the last winter we'll be able to use it.”

It turns out, the Mössbauer was acting up because the voice coil that drives its source doesn't always work, said Nelson. "We know this voice coil circuit is temperature sensitive. And we've been turning it on and just integrating in error. We don't care about the actual numbers we get, but doing that gives us an error signal that’s supposed to hold to a particular profile. This error signal tells us basically how close to the profile the instrument is at. And when it's operating, the error signal is pretty small and when it's not, it's not. So, by turning it on at various times during the day, we're characterizing the temperature at which it's known to work,” he explained. “By changing the temperature range that the voice coil is operating in, we can narrow effectively narrow the bandwidth we're looking in and that should help improve the signal-to-noise ratio. Now we have some rough guidelines based on some limited testing, and we've done more testing to get a better handle what’s going on,” he added.

The Mössbauer has been cleared to be used, Nelson said. "But we're kind of between a rock and a hard spot on this,” he added. “It works at warmer temperatures, but warmer temperatures means the molecules have greater thermal random motion so it tends to smear out the peaks a bit. But anything you can do to improve the signal is a benefit. So by limiting the range the voice coil goes through we seems to be able to do that a bit.”

As the third week of January took hold, Opportunity pressed on, methodically performing every engineering task and science assignment, including regular radio Doppler tracking measurements to support geo-dynamic investigations of the planet, imaging for the Greeley Panorama, and in-situ or contact science investigations of Amboy. Additionally, the rover spent time taking an extensive number of MI pictures even as the brutal Martian winter took temperatures lower.

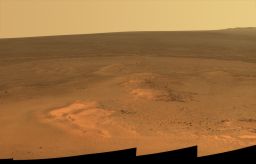

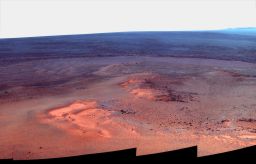

Looking north from Greeley Haven

Looking north from Greeley HavenThis mosaic of images taken in mid-January 2012 shows the windswept vista northward (left) to northeastward (right) from the location where Opportunity is spending her fifth Martian winter, an outcrop informally named Greeley Haven. The rover used her panoramic camera (Pancam) took the component images as part of full-circle view being assembled from Greeley Haven. The view includes sand ripples and other wind-sculpted features in the foreground and mid-field. The northern edge of the the Cape York segment of the rim of Endeavour Crater forms an arc across the upper half of the scene.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

"We are going to take advantage of being parked [at Greeley Haven] for a long time to build up what I think should be a pretty substantial MI mosaic of this outcrop,” explained Squyres. “We can take a whole bunch of microscopic images that we can then merge, or mosaic together a very long strip of MI imaging that I think will be quite nice. We're working that out one frame at a time,” he said.

On Sol 2839 (January 18, 2012), Opportunity collected the first frame of that extended MI mosaic, then placed her APXS on Amboy. The next sol she continued to check out the Mössbauer to try and find the best time of day to deploy the instrument, and conducted a radio Doppler tracking pass. The rover retracted her APXS on Sol 2841 (January 20, 2012), and rotated the instrument skyward to conduct a periodic atmospheric argon measurement.

Mid-month, Opportunity was still producing around 276 watt-hours and the haze in the sky diminished slightly. The rover measured atmospheric opacity or Tau at around 0.602, and a solar array dust factor of 0.447.

With winter solstice just around the corner however, decreasing energy levels and the increasingly colder temperatures began to constrain the rover and her team. Opportunity was no longer able to conduct both a radio Doppler tracking pass and an afternoon ultra high frequency (UHF) data relay pass on the same sol. “We just don’t have the power,” said Callas. “It draws too much energy from the batteries.”

As a result, the flight ops team began the delicate dance on the tactical timeline, crunching the fading energy numbers to decide which of the two communication passes would be performed in a given sol.

Greeley in winter in false color

Greeley in winter in false colorThis mosaic of images taken in mid-January 2012 shows the same windswept vista northward (left) to northeastward (right) from the location where Opportunity is spending its fifth Martian winter as in the image just above, butin false color. By processing images in false color, scientists can easier see distinguishing features that may exist in the rocks and terrain.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

Even so, Opportunity seemed to cruise through the last week of January, figuratively speaking that is, moving from one science project to the next, working as diligently as she ever has. On Sol 2844 (January 23, 2012), the rover took more pictures for the Greeley Pan and the calibration target with her Pancam, then repositioned her instrument deployment device (IDD) / robotic arm in order to collect a set of MI sky-flat calibration images the following sol.

“We use these sky-flats to characterize the sensor to see if we have any new bad pixels, whether we have bias of voltages and other related engineering issues,” Nelson said. “You have to look at what is effectively known blank screen to do that. So the object with the sky flats is literally to take a picture of the sky, in this case with the MI. Of course it will be grossly out of focus, but that's okay. If everything is perfect, we're going to see this kind of uniform grey image with nothing on it. That's what we'd like to see. What we're actually going to see is a more or less grey image, with some mottling from dust and little bright and dark pixels that have failed in one way or the other. We may even see some systematic gradation in the color,” he said.

On the morning of Sol 2845, the rover pointed her MI to the sky as commanded. "Our prediction was that the MI would be in shadow, which is what we wanted," said Nelson. "It turned out that the prediction wasn't correct and the images were partially sunlit. And the sunlight reflects off the dust that's on the lens and it kind of washes out everything else. It's the same kind of thing you experience with fine dust on your windshield as you're driving into the Sun.”

Since the dust in the skyflats wasn’t uniform in those images, the pictures were unusable for the purpose of characterizing the instrument’s sensor, and the session had to be rescheduled.

That same sol, Opportunity took the daily Tau measurement with her Pancam to monitor the dust in the sky – and then did another with her navigation camera (Navcam). "Every day we do a Tau, which is intended to tell us how much sunlight is extinguished by dust in the air," pointed out Nelson. "But there's also dust on the lenses and we need a way of figuring out whether the images are being dimmed by dust in the air or dust on the lenses. So, we periodically take a second Tau with a second camera, which has a different dust loading, to be able to tease out the difference. That allows us then to apply a correction for the camera dust, and that's why we took the two Taus, Pancam and Navcam that day."

Clouds over Endeavour

Clouds over EndeavourOpportunity used her navigation camera to take images of the sky over Endeavour in January 2012 in a search for water-ice clouds that form during wintertime on Mars. Stuart Atkinson took the raw images and "skilfully manipulated" them using Photoshop to bring out more detail, then put them together in sequence to create this short animation.For more of Atkinson's work, visit: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / S. Atkinson

Opportunity then turned her attention and Pancam to focus on pictures for the Greeley Pan and of the calibration target. Following that, she undertook a "bitty cloud" search with her navigation camera, basically taking a sub-framed image of a targeted area of the sky to look for water ice clouds characteristic of wintertime. And toward the end of the sol, the rover even squeezed in another radio Doppler tracking pass. It was a full sol's work to be certain. But it was a sol that corresponded to a day on Earth that was memorable for other reasons.

On January 24, 2012, the rover's Sol 2845, the MER mission completed its eighth year of exploring Mars, but there was no formal celebration at JPL or elsewhere and Opportunity and the team worked on.

Outside the space community, many people it seems have come to take the notion of rovers on Mars for granted, if they're aware of what's going on outside their own little world at all. Squyres and the MER team never will. "We never want to get into a mode where we take these things for granted," the team's chief scientist said. "Every day now truly is a gift. But this is a Mars mission, and Martian years matter to me more than Earth years. Martian sols matter more than Earth days do.”

While Opportunity worked through her 8th anniversary, as fate would have it, she was, given the next sol off, however inadvertently, when the team's commands failed to get to the rover. "We were intended to use a -5000 Hertz offset, and we ended up having them use a -50,000 Hertz offset," explained Nelson. “In effect, instead of tuning to where the [DSN] station is, we tuned to somewhere else,” he said.

Opportunity received her commands on Sol 2847 (January 26, 2012) and completed her assignments. In the sols follow, the rover finished out the month continuing her work on the three prime science directives, as well as taking daily Taus measurements to monitor the dust in the sky, Pancam images of the calibration target, a few "bitty cloud" searches with the Navcam. And, when radio science passes were scheduled for late in the day, Opportunity rose early and pointed her Pancam here and there snapping pictures of rugged, ancient terrain along Endeavour’s rim.

"Generally the radio science passes turn out to be late in the day, not too long before sunset, and so the other thing we're doing that is kind of interesting, when we do radio science, is low light imaging with the Pancam," said Squyres. "When the Sun is low in the sky, it casts long shadows out into [Endeavour Crater]. Because of the low illumination, we can see subtle windblown features like ripples, and drifts and small dunes with much greater clarity. So these images enable us to see Aeolian, windblown features that we normally wouldn't be able to see as well. We've gotten some really very spectacular images, and so we're going to continue to do this.”

Over yonder

Over yonderOpportunity used her Pancam to take the raw images of the hills on the far side of Endeavour Crater, which Stuart Atkinson then processed and produced in color as presented here. For more of Atkinson's work, visit his Road to Endeavour blog at: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/ Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell / S. Atkinson

Science aside, the low illumination images are striking visually, Squyres noted, featuring “a sort of Ansel Adams quality.” Although some of them, he added, are “pretty cool” in color too. “We recently did a color lowlight image that, when it's all put together, I think is going to be pretty nice. You can see the rover's shadow off in the distance in this one," he said.

For the most part though, Opportunity is focused on the winter science campaign. "We’re in a fantastic place, and we are steadily, continuously collecting radio science data," Squyres began by way of summation. "We've got a good target we're working on, Amboy, and we've got really good APXS data on it now. We're continuing with Mössbauer integrations on it and, after the troubles we had with it this month, we are getting data. We're taking the Greeley Panorama. The top two tiers are done and we're getting to work on the lower tier. It’s going to be one of the signature images from this mission once it’s finished.”

"It will be a spectacular and, of course, emotional data product," elaborated Bell of the Greeley Panorama. "I am sure that when we look back on this time and these measurements being made over this fifth Martian winter in Meridiani, we will also be thinking of our colleague Ron Greeley, and how much he meant to our team and the broader community of planetary scientists."

As January 2012 came to a close at Meridiani Planum on Sol 2852 (January 31, 2012), the solar-powered rover was producing about 260 watt-hours of power, recording a Tau of 0.693. "We're right in that 270 watt-hour predict area, plus or minus 10, and we probably have between 20 and 40 watt-hour uncertainty in that," said Nelson. In other words, the Martian environment at Opportunity’s site is in line with the predictions.

"We are already having to trade off radio science for the data downlinks, the Greeley Panorama, Mössbauer and APXS," added Arvidson. The science work will become more and more reduced, he added, "and then after March we'll come back up. The priority is that we get a good series of radio science data, and then everything else."

Greeley Haven on the map

Greeley Haven on the mapOpportunity is spending her fifth Martian winter working at Greeley Haven. This site features an outcrop near the northern tip of the Cape York segment of the western rim of Endeavour Crater. It provides a north-facing slope of 15 degrees or more to help maintain energy output from the rover's solar array. It also presents geological targets of interest for investigating during months of limited mobility while the rover stays on the slope.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA

If everything continues as predicted and expected, Opportunity will work through the winter. At the same time, this is Mars and Opportunity is an old rover. Anything can happen anytime.

There is always concern, said Callas. “We have decreasing power levels and dust building up on the solar arrays, and if these trends continue we will be doing less and less science each day or each week for the next couple of months.”

Another potential annoyance could occur with the rover’s survival heaters if Opportunity gets too cold. Since the beginning of the mission back in 2004, this rover has gone into what's called DeepSleep mode at night, essentially turning off everything, because a heater inside her rover electronics module (REM) is stuck in the "on" position. As winter progresses, those heaters could become problematic even as they do what they were designed to do – keep the rover warm enough to survive, said Callas. "As we get less energy to be active with, that means there's less heat to keep the rover warm. It’s just like a human out in the winter cold and bundled up moves around to stay active to generate heat. If you're nutritionally starved, then there's not a lot of energy for you to expend to generate that heat to keep you warm. Same thing with the rover,” he explained. “So yes there is a concern about the DeepSleep mode.”

The problem that could occur is when the rover comes out of DeepSleep in the morning. If the rover is too cold there’s a chance that the survival heaters in the rover electronics module (REM) could come on. “And they suck a hell of a lot of energy,” said Callas. “So even though we may have adequate power margins during the winter when we're DeepSleeping, there is a possibility that the rover gets cold, because it's wintertime, and it's not as active as in previous years, the REM could get colder, to the point where it could trip the thermostat for those REM heaters during that brief window when we come out of DeepSleep mode and before the rover first wakes up. That would mean we would have to spend days recharging the batteries, and that would steal science from us if that happens."

The objective now for the rover engineers and handlers is to try and balance activities keep the REM warm enough to prevent the heaters from coming on, but not so active that it would deplete the batteries and prevent the team from conducting science when they want or need to. “We're managing the power levels and the activity of the vehicle to keep it warm enough that we avoid the possibility of the REM heaters coming on and drawing energy out of the batteries. We would rather put energy into the rover through a controlled method of keeping the rover active rather than heating the rover through the REM heaters, in order to use the energy more efficiently," said Callas.

So far – all things considered in a Martian winter – so good. Everything is going according to plan and predictions. "It's still trending the way we expected. We'd like a cleaning event, but we can't schedule those," said Callas.

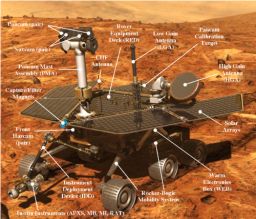

MER body parts

MER body partsThe Mars Exploration Rovers are robot field geologists that were designed with parts to substitute for the organs all living creatures would need to stay "alive" and able to explore, as well as some super-human powers. Spirit and Opportunity, for example, each have a body that protects its "vital organs;" brains to process information; temperature controls, including internal heaters, a layer of insulation, and more; a "neck and head" formed from a mast for the panormaic cameras for a human-scale view; eyes and other "senses," such as cameras and instruments that give the rovers information about their environment; an arm to extend its reach; wheels and "legs," necessary parts for mobility; and energy sources in the form of batteries and solar panels; and antennas for "speaking" and "listening."Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

Down on Earth, the scientists are burning the midnight oil. "The [radio science] data look good," said Bill Folkner, after having run the data for the first week of January. "I now need to modify my analysis software to account for the motion of the HGA on the rover, which moves as a function of time depending on how the rover is oriented, and it moves during the tracking pass to keep the antenna pointed at the Earth. So just like a big dish would slew across the sky to point at Mars, this is a small dish that's pointing basically at the Earth, and so it's moving, and my software that I usually use doesn't have that motion programmed in yet," he explained.

Although he still has to analyze the data from the last three weeks, Folkner said he thinks he and his team may already have enough data to get the direction that the Mars spin axis is pointing with enough accuracy that they can compare that direction to the direction it was pointing in during the Mars Pathfinder mission in 1997, and estimate the rate of change of the spin axis vector.

"With Mars Pathfinder, we used the difference in the spin axis direction determined from Pathfinder with what we got from the Viking lander back in 1976. The Viking data was not as accurate because the radio frequency used at that time was more susceptible to noise from electrons emitted by the Sun than the radio frequency we used for Pathfinder and are using now for MER, but the Viking data covered more months than Pathfinder did,” Folkner pointed out.

"The rate of change of the spin vector depends on the distribution of mass within Mars, acting from the torque of the Sun on it," Folkner expounded. "The mass of the Sun pulls on the mass of Mars a little bit differently. It pulls more on the mass of Mars that's closer to this end, [rather] than on the other side of Sun. Because Mars is [an] oblate [spheroid], flattened a little bit, that [pull] changes with time. By measuring the rate of change in that from Pathfinder and Viking, we got enough information to determine that the egg-shaped Mars was not uniformly dense, but had a denser core, which everybody expected – that was the first to actually show that," he noted.

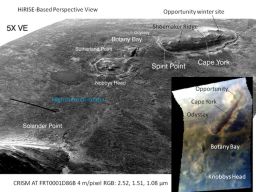

Opportunity's roving grounds

Opportunity's roving groundsThis graphic combines a perspective view of the Botany Bay and Cape York areas of the rim of Endeavour Crater on Mars, and an inset with mapping-spectrometer data. Major features are labeled. In the perspective view, the landscape's vertical dimension is exaggerated five-fold compared with horizontal dimensions. Opportunity examined targets in the Cape York area during the second half of 2011. The perspective view was generated by producing an elevation map from a stereo pair of images from the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, then draping one of the HiRISE images over the elevation model.Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UA/JHUAPL

Now, with MER, Folkner is looking to improve that number. "I suspect with the data we have now, we can determine that rate of change of that vector – the spin axis direction if you like – probably by a factor of 2 better than we know it already. Which is pretty good considering the rover is not designed to do this," he offered.

“By improving by a factor of 2 the moment of inertia of Mars, or the precession rate, (which is related to the moment of inertia), we can rule about half of the interior models we have, but it doesn't map well with any one parameter, like the radius ... it's a little bit complicated,” said Folkner. “What we hope to see if we take enough data is, in along with long term drift or precession, we should see the spin axis of Mars wobble. It has an annual and semi-annual wobble. How much it wobbles is not only on the mass distribution, but on whether the core is liquid or not.”

Being able to determine if the core unequivocally is liquid “would be good,” offered Folkner in something of an understatement. “To determine whether the core is liquid we need to see this half a Martian year period [one Earth year] in the wobble of Mars. We know we can get that if we could have 12 Earth months or one-half Martian year [to gather] Doppler data with the rover being either fixed or moving short enough distances that we can measure the changes in its movement accurately enough to make use of the radio data."

However, with the Pathfinder data, which was taken at a different time of the Martian year back in 1997, Folkner suspects he might be able to "see" the wobble in less time. "I plan to do the simulations for that next week," he said.

At this point, scientists think the core is fluid but there are discrepancies in the orbiter data. Opportunity's effort would confirm if Mars' core is fluid. "And it would also tell us something about the density of the core – and that tells us something about how the core was formed and that's new information that the gravity variation [which the Mars orbiters are observing] doesn't measure. So there are reasons to get beyond confirming that the core is liquid," he said. "Although, that's the neatest thing."

Despite the unique camaraderie and esprit de corps among team members, there is always some tension over what the rover should do next, scientifically speaking, and a lot of factors come into the play of those decisions at the regular Science Operations Working Group (SOWG) meetings. "Right now, our power situation is not dangerous, but it's not enabling us to move anywhere. We're going to be here for a while,” said Squyres.

Just how long Opportunity will stay parked, only time will tell. True to form, Squyres is making no promises. Everyone who knows this mission however knows that Opportunity loves to rove – and that there is scientific gold – clay minerals – waiting in the hills to the south.

“Once the power situation begins to improve, we'll see where we are,” Squyres said. “That’s all I can say for now.”

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth