A.J.S. Rayl • Jan 31, 2011

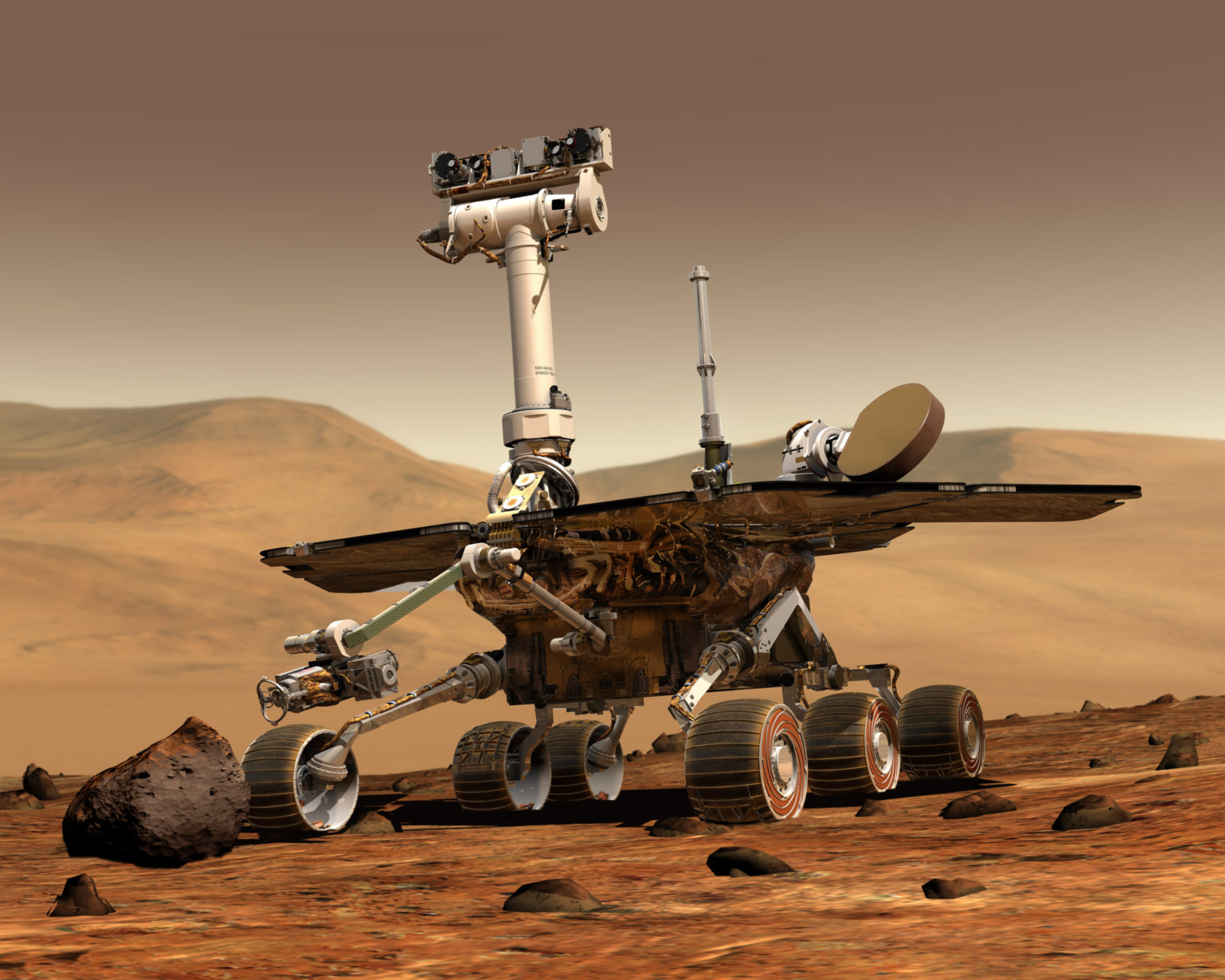

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Mission Celebrates 7 Years of Exploration

Seven years ago this month, Spirit bounced down onto the surface of the Red Planet, rolled to a stop upright, and beeped home, ready to roll. Three weeks later, Opportunity not only bounced down safely and right into a small crater, but opened its "eyes" to see what the Mars Exploration Rovers had been sent to find – signs that water had once flowed there.

On those January nights, dozens of journalists and "vips" descended on the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the home the rovers left some 9 months before. For the first time in planetary exploration history, the public was invited along – with an almost all access backstage pass – via the Internet.

"They are emissaries not just of NASA or the United States, but of the planet Earth," Steve Squyres, the principal investigator, of Cornell University, said then.

Earthlings everywhere embraced them. More than one billion people from around the world jammed the NASA/JPL websites and their mirror sites in the first 72 hours, setting an Internet record. Hundreds of millions more jumped online as the mission continued.

When their first images arived on Earth, everyone around the world was able to see them at the same time as the scientists. It didn't matter if you were viewing them from afar, or in the JPL auditorium, and it didn't matter what country you were in, or if you were a journalist or enthusiast or blogger or student or a politician or just someone curious, for a few fleeting moments on January 3, and January 24, 2004, (Pacific Standard Time) all was right with the world. We had just put two robot rovers on Mars and there in our hands was an irresistible ticket to ride, free of charge.

Within their primary 90-day mission, both Spirit and Opportunity discovered evidence of past water, and then kept roving, continuing the exploration on opposite sides of the planet, and earning the distinction last year of being the longest lived surface mission on Mars.

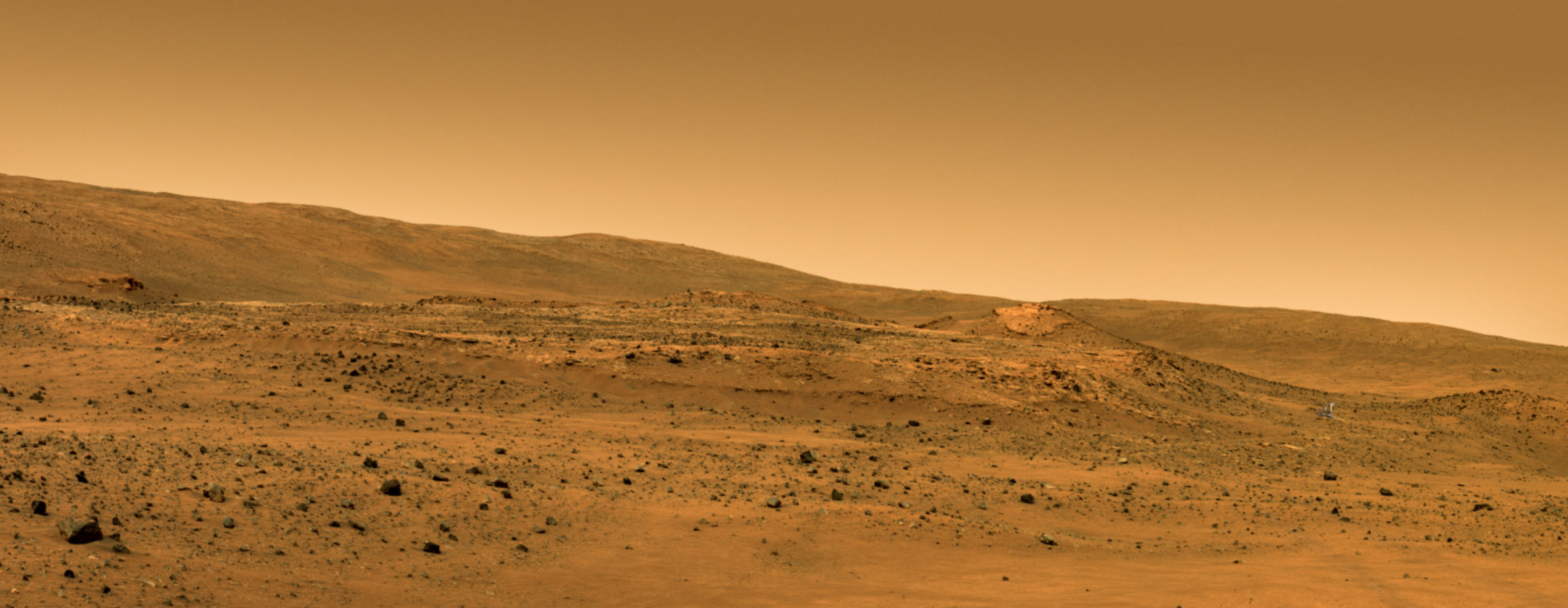

From its landing site in the grand Gusev crater, Spirit roved through often treacherous terrain to Bonneville crater, and then onto a distant set of hills named after the Columbia space shuttle crew that lost their lives in February 2003.

From the foothills, the rover set out to climb what appeared to be the tallest peak, Husband Hill. Slowly but surely, the rover made it to both of Huband Hill's two summits becoming the first robot to scale a hill the height of the Statue of Liberty on Mars. It was a significant achievement for the rover, as well as the mission.

In early 2006, Spirit headed for the next hill, named after Willie McCool, Columbia's pilot, to park for its second Martian winter. But en route, its cantankerous right front wheel locked for good, transforming the rover into a five-wheeled vehicle and meaning it would have to drive backward there on out.

It was a handicap that made future mountaineering all but impossible. With winter coming fast, Spirit roved on, backwards, to a nearby northern rise nicknamed Low Ridge, not far from the base of McCool Hill. Seven months later, Spirit shook off the cold and back-tracked to an intriguing, eroded over, circular volcanic formation it had passed on the way to Low Ridge. Because this formation was effectively a little plateau, the team dubbed it Home Plate, and the rover dug in for has become an extensive years-long study to tease out the story of past environments there.

In various places around the perimeter and in the nearby area of Home Plate, Spirit inadvertently churned up with its lame right front wheel lush white and yellowish silica-rich soils, clear evidence of past water and one of the MER mission's top discoveries. It was a finding that bolstered the theory that Home Plate was the site of an old volcano and water was present in the area in the form of hot springs and/or fumaroles.

With the rovers' third Martian winter on the horizon, Spirit roved across the top of Home Plate, perched itself on the edge, and beat the odds again. As spring finally began to warm Gusev Crater, the rover was unable to drive back on top of Home because of its right front wheel, so it backed down and roved on, taking the long way, around the northern tip of Home Plate and down along the western edge, heading for its next destinations to the south.

As Spirit was roving through an area called Troy in April 2009 it suffered a series of bewildering reboots and amnesia. After recovering, it moved on, but then without warning its left wheels broke through the crusty ground cover and slipped on the edge of a hidden, shallow, sand-filled crater.

Spirit tried to maneuver its way out, but only dug in deeper in May, at which point the team commanded the rover to stop trying. The MER team spent six months in the Mars yard at JPL trying to simulate the rover's sandy soils and figure out how to command it to extricate itself. The campaign to Free Spirit began on Mars in November 2009. It wasn't until they changed the drive strategy in January 2010 that the rover began to make progress. By then, the MERs fourth Martian winter cold was bearing down, usurping the rover's power and stopping the action. Mired in the sands of Ulysses, along the western edge of Home Plate, Spirit had no choice but to hunker down and try to hold on.

Spirit's last communiqué to the MER team on Earth was on March 22, 2010. Now, some 10 months later, the rover sits – perhaps trying to communicate, perhaps not. Right now no one knows. During the extrication attempts, the rover's rear right wheel stopped working, making it effectively a four-wheeled rover. All good things and all good rovers eventually come to an end, true. But if there's one thing the MER team and its legion of followers have learned: Don't bet against Spirit.

"It's wait and see," said Ray Arvidson, deputy principal investigator, of Washington University St. Louis.

Always the luckier of the twin rovers, Opportunity made quite a grand entrance onto Mars, scoring "the world's first 300-million-mile, "interplanetary hole-in-one," as Squyres described it, bouncing to a landing right inside Eagle Crater in the Meridiani Plains. When the rover opened her "eyes," she was staring into the first bedrock seen on Mars, something that shook the bleary-eyed scientists. The clues for past water were right there before her. Before the primary mission was over, the MER team announced that Opportunity had sent home the gold -- evidence in minerals and rock textures that showed a large body of water, perhaps, a salty sea, drenched the surface there in the past.

On the other side of Mars, Opportunity is closer to the equator than Spirit and in a much less hostile part of the planet than her twin. She has always had the easier road to rove. After a thorough investigation of Eagle Crater, Opportunity rolled out onto the vast Meridiani plains toward some intriguing craters to the south, setting and then breaking drive records along the way. The rover made extended science stops at Endurance Crater and Erebus Crater to analyze the layers of bedrock seen there.

Within Opportunity's datasets, the MER scientists were finding that the evidence pointed to changing environmental conditions in the past. The water table once there long, long ago fluctuated, it appeared, and the wind blown sand dunes came and went as it did. Looking like little, still form waves rolling across the Meridiani landscape, it turns out they were sculpted, theory now holds, by one or more ancient seas.

From Erebus, Opportunity began the 21-month-long journey to Victoria, an 800-meter- (half-mile) wide crater. It pulled up to Victoria's rim in September 2006 and spent two Earth years studying the big hole in the ground. The patterns in the layerings in Victoria's walls "definitively speaks of this being dune deposits," Squyres noted then.

When its work at Victoria was finished, Opportunity in October 2008, set out on the journey of its lifetime toward Endeavour Crater. At 22 kilometers (13.70 miles), Endeavour is likely the largest crater Opportunity will visit.

Since leaving Victoria, Opportunity, which lost the use of one of its instruments during the global dust storm of 2007, has suffered some mechanical injuries presumably due to aging. An arthritic right front wheel and a broken shoulder joint have this rover also driving backwards these days, with its instrument deployment device (IDD) or robotic arm in a slightly unstowed or "fisherman position."

Nevertheless, true to the MER mettle demonstrated throughout the years, Opportunity pressed on, logging 7.4 kilometers (4.6 miles), more miles than in any other single (Earth) year. Just last month, the rover pulled up to Santa Maria, a fresh, football field sized crater and the last major geologic formation on the long journey to Endeavour.

Together, Spirit and Opportunity achieved many robot 'firsts' on Mars. They found the first hard evidence for past water trickling underground and pooling on the surface. They found meteorites and snapped pictures of the planet's infamous dust devils, and checked out one of their heat shields. They climbed a Martian hill, forged across ancient salty sea beds, drove into craters, picked through rocky landscapes, cruised across plains, and taken the most glorious pictures ever snapped on the surface of Mars. Through it all, they seemed uncannily determined, allowing neither dust storms, or gnarly sand dunes, or treacherous terrains or anything else to keep them from their mission.

No one really expected either Spirit or Opportunity to survive much past their three-month primary mission, and certainly not through the Martian winter that would come just a few months after that. The twin robot field geologists kept going and going, seemingly "kissed" by Mars with dust-clearing gusts of wind that cleared their solar panels, enabling them to keep on taking in and producing energy from the Sun. Given the desolation, dust and danger on Mars, it is nothing less than remarkable by any account. But the MER 7th anniversary came and went with little fanfare.

“I think it's because we've become very workman-like in our approach to the rovers – and it's seven years, and we've celebrated other anniversaries,” said Arvidson. In addition, many of the MER team members are working double-duty on the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) and the rover Curiosity, which is slated to launch toward the end of this year.

At JPL, the MER ops crew did have a small team gathering over cupcakes last Thursday. Planned by John Callas, MER project manager, the program featured From the Earth to the Moon Episode 4. "The team members were thanked for all their hard efforts, including getting ready for solar conjunction (now started)," reported Nelson. "There was no recap of the mission, no long speeches, just cupcakes, each with a letter in icing spelling “Happy 7th Anniversary Opportunity!!” (Yep, two exclamation points due to the size of the cupcake tins)." The celebration was short, he added, so the movie could start.

That same day the orbits of Earth and Mars put the two planets on the opposite sides of the Sun – or – from our perspective down here, it put Mars directly behind the Sun. During the days surrounding such an alignment, called a solar conjunction, the Sun can disrupt radio transmissions between Earth and Mars. To avoid the chance of a command being corrupted by the sun and harming a spacecraft, NASA temporarily refrains from sending commands from Earth to Mars spacecraft in orbit and on the surface.

“If a command is corrupted by the solar interference it can have catastrophic affects,” said Bill Nelson, chief of rover engineering team, JPL. "It could, for example, cause the rover to do something it shouldn't, so we are very, very careful not to send commands when they could be corrupted." This year, the commanding moratorium will be January 27 to February 17 for Spirit, January 27 to February 11 for Opportunity.

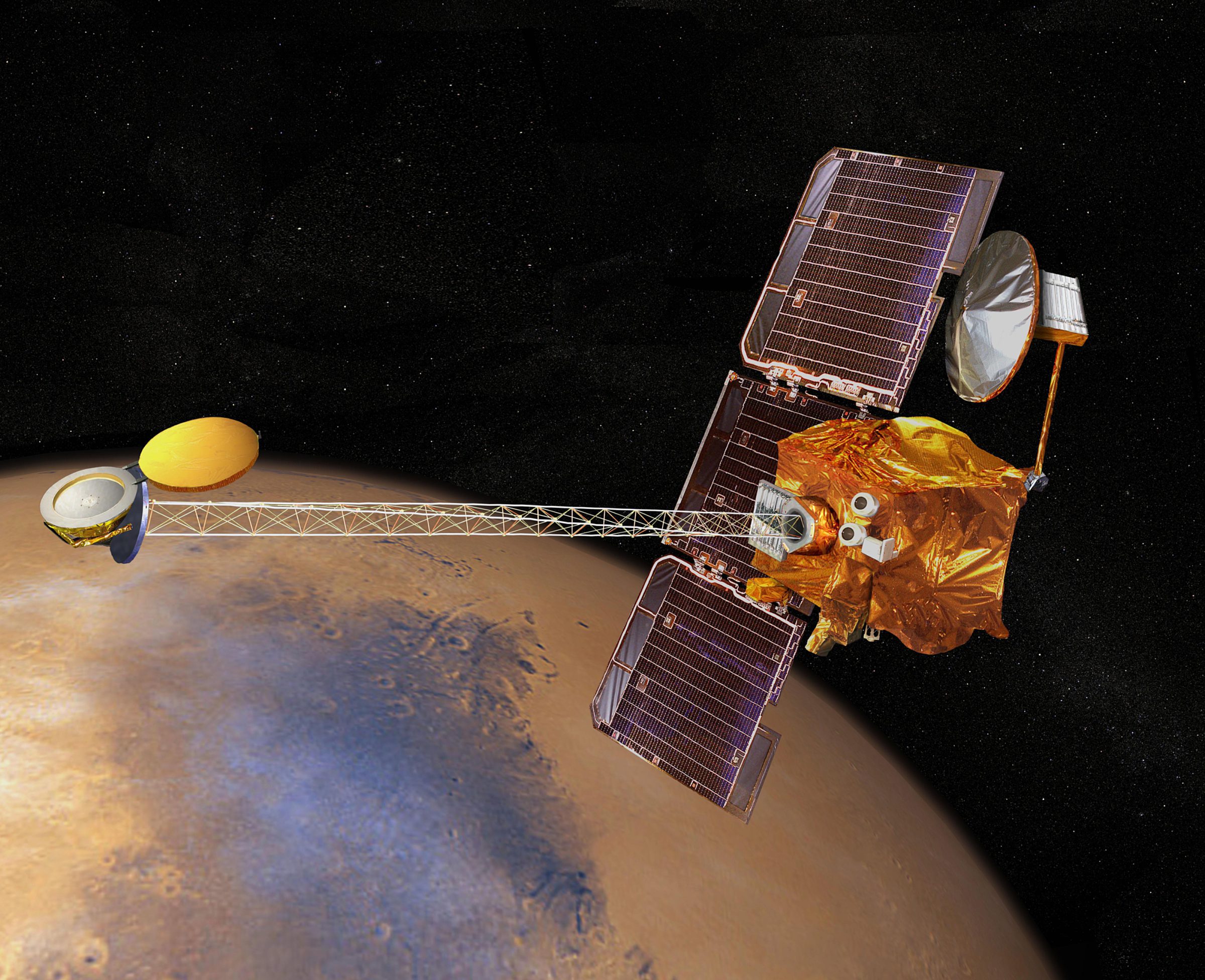

For this 16-day commanding stand-down, Opportunity is parked along the southeast rim of Santa Maria, in an area where the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM), a visible infrared spectrometer onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), detected evidence for hydrated sulfate minerals. There, on the edge of what may – or may not – be a smaller impact crater along the side of Santa Maria, a place the team calls Yuma, the rover is now conducting an extensive investigation to try and determine the composition of a target called Luis de Torres and the source for the hydrated signal that CRISM found from orbit.

"Once solar conjunction passes, Opportunity will finish up at Santa Maria and then blast across those 6000 meters to Capre York at Endeavour," said Arvidson. With portions of the monster crater's rim on the horizon, the once dream-of-a-destination is in view and all eyes are squarely on the big prize.

Spirit and Opportunity have become robot stars and legends in their own time. Although there is surely more to come, no matter what happens they will always have a special place in history.

“The journey of these rovers have been motivated by science, but have led to something else important – humanity's first overland expedition on another planet,” as Squyres has said on more than one occasion to this journalist: “When people look back on this period of Mars exploration decades from now, Spirit and Opportunity may be considered most significant not for the science they accomplished, but for the first time we truly went exploring across the surface of Mars."

Spirit from Gusev Crater

January came and went with no beep to be heard from Spirit. The JPL Radio Science team continued throughout the month to listen with the Deep Space Network (DSN) and the Mars orbiters for an autonomous recovery communication from a low-power fault case, and continued reaching out with the sweep-and-beep paging strategy to nudge the rover in the case it also tripped a mission-clock fault and is waiting on a command from Earth.

The last communication received from this rover was more than 10 months ago on Sol 2210 (March 22, 2010).

It may be that the rover has been trying to reach out or respond, but it's clock has drifted more than estimated, so the team also began this month to expand the time windows during which it listens, just in case the rover is locking up at a different time on the signal to the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (which shares the same direct-to-Earth X-band frequency channel). It also expanded the time window for the sweep-and-beep commanding, and the DSN crews began using different frequency reference offsets in the case Spirit's receiver's frequency response has drifted.

In the sols following the solar conjunction, beginning on February 17th, the Radio Science team will step up the game. “We're going to be more aggressive in what we're doing," said Nelson. "We're still trying the same strategies, but we will be listening earlier and later in case the clock has drifted a lot more than expected and we will continue listening at higher and lower frequencies in case the oscillator has drifted more than we expected. So we'll be going through a wider range of both time and frequency," he summed up.

The rover engineers at JPL are also in the process of doing further fault analysis to determine what other faults might have occurred that are still recoverable. "There aren't that many," noted Nelson. "And it turns out what we're doing covers many of the recoverable faults."

For example, they are going to command through the X-band back-up, the solid state power amplifier (SSPA). "That's one of the few redundant pieces we have in the X-band system," Nelson pointed out. "Most of it [rover system] is what we call single string and has no back-up, but this is one exception. So we'll try commanding on the back-up SSPA and we'll try commanding through UHF in case the problem is the X-band receiver is broken. Right now, we've been commanding on X-band and listening on X and UHF. Now we'll command on UHF and continue to listen on both to see if that works. We'll be doing a few things like that, but our options are pretty limited on what we can do."

The period of maximum solar insolation – when the position of the Sun enables the most energy in-take and production for Spirit – occurs around mid-March 2011, so no one's giving up yet. However, while the MER team maintains cautious optimism that the rover will be phoning home soon, with every passing sol, that optimism is being challenged. The rovers are getting old and Spirit has had to deal with a much more unforgiving landscape and harsher winter temperatures than her twin. "We are pinning a fair amount of our hopes now on clock drift or oscillation drift," Nelson said. And, no doubt, the never, never, never give up "attitude" consistently demonstrated by their charge.

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

As the New Year dawned on Earth, Opportunity continued to explore the 80-90 meter (262-295 foot) diameter Santa Maria Crater on Mars, shooting wide-baseline pictures with both her navigation camera (Navcam) and panoramic camera (Pancam) from several points around the rim of the crater. The rover arrived at Santa Maria, the last major geologic feature on the rover’s long journey to Endeavour Crater, last month.

Opportunity worked through the New Year's holiday weekend, conducting a three-sol remote sensing imagery campaign on Sols 2465, 2466, and 2467 (December 30, December 31, 2010, and January 1, 2011). On the next sol, 2468, the rover drove more than 56 meters (184 feet) south/southeast, moving counter clockwise around the crater to set up for the next wide-baseline stereo pictures. Then on Sols 2469 (January 3, 2011) and 2470 (January 4, 2011), the rover completed taking the assigned pictures of Santa Maria and the surrounding area, and also collected an alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) measurement of atmospheric argon.

A planned drive on Sol 2471 (January 5, 2011) did not occur, because the rover detected an error in the drive sequence sent from Earth. This was corrected and as the second week of the month got underway, Opportunity drove on, heading for the southeast rim where CRISM detected the signature for hydrated sulfate minerals. The rover covered more than 78 meters (256 feet) on her jaunt around the southern edge of Santa Maria on Sol 2474 (January 8, 2011).

The MER scientists and engineers decided Opportunity would park for solar conjunction at a place the team calls Yuma. This intriguing dip may or may not be a smaller, shallow, perhaps ancillary impact crater along the southeastern edge of Santa Maria. On Sol 2476 (January 10, 2011), the rover made a 15-meter (49-foot) approach to the chosen spot at Yuma. And on the next sol bumped about 3 meters (10 feet) to position herself at a bright surface target called Luis de Torres. From there, the rover took the assigned wide-baseline stereo pictures of the crater, as well as additional images of the area, including more pictures of Endeavour, and its routine atmospheric argon measurements.

Then, on Sol 2478 (January 12, 2011), Opportunity performed a small, approximately 4.6 degree turn to position her robotic arm or instrument deployment device (IDD) to within reach of Luis de Torres, then used her hazardous camera (Hazcam) to take some images of the immediate workspace. A DSN issue delayed the return of data, so continued robotic arm activities were put on hold.

As the third week of January got underway however, Opportunity began the planned in-situ or contact surface science campaign using her microscopic imager (MI) to take a series of pictures for a mosaic of the surface on Sol 2481 (January 15, 2011). Then, she placed her APXS down for a multi-sol measurement.

On Sol 2484 (January 19, 2011), Opportunity lifted the APXS from the target and positioned her rock abrasion tool (RAT) for a grind-scan in preparation for brushing the target on a subsequence sol and subsequently cleared the target of its topmost surface layer. “We did MIs and APXS on a natural surface and a brushed surface on Luis de Torres,” confirmed Arvidson.

The data is still coming down and the analysis has only just begun, Arvidson said. "We've got a real signature [for hydrated minerals] from CRISM, but we're going from 18 meters per pixel down to a 4-centimeter wide area with Luis de Torres and we're trying to figure out what the data we have all means. Unfortunately Mini-TES is in stand-down mode. That would have been the ideal instrument to corroborate the hydrated sulfate detection, but at this point we have to use Mössbauer, APXS, and Pancam multi-spectral imaging and we will have to do a lot of detective work before we will be able to make sense out of it all.”

Solar conjunction began last Thursday, January 27, 2011, so the final day of pre-solar conjunction planning for Opportunity was Wednesday. The team will not be uplinking any commands to the rover again until February 14, 2011. Although the rovers' team on Earth had to temporarily suspend commanding for 16 days, Opportunity is staying busy. The team developed a set of commands that were sent up to the rover in advance.

Despite the command moratorium, downlinks from Mars spacecraft will continue during the conjunction period, but at a much-reduced rate. Mars-to-Earth communication does not present risk to spacecraft safety, even if transmissions are corrupted by the Sun, so Opportunity will send data daily to the Odyssey orbiter for relay to Earth, but at a much reduced 32-kilobit rate. [The rovers typically send data at 128 or 256 kilobits rates.]

"Overall, we expect to receive a smaller volume of daily data from Opportunity and none at all during the deepest four days of conjunction," said Alfonso Herrera, a rover mission manager at JPL. Those "deepest four days" are when the Sun-Earth-probe angle is at its minimum, as viewed from Earth.

"We're not giving Odyssey a lot of data, because there is a fixed buffer size on the orbiter and we don't want to overflow that buffer if for some reason the orbiter is not able to send that data back," expounded Nelson. "This solar conjunction though is pretty benign, so while some of the data may be a little ratty, we'll probably get data through most of this particular conjunction."

If Opportunity's data doesn’t make it intact or is otherwise corrupted or lost, it will still be on the rover and re-sent later. The computer in each MER runs with a 32-bit Rad 6000 microprocessor (a radiation-hardened version of the PowerPC chip used in some models of Macintosh computers) operating at a speed of 20 million instructions per second. Onboard memory includes 128 megabytes of random access memory, augmented by 256 megabytes of flash memory and smaller amounts of other non-volatile memory, which allows the system to retain data even without power.

“We prepared as we usually do for solar conjunction by giving the scientists a decreasing amount of flash that they were allowed to use – or put another way, an increase amount of flash that had to be reserved for conjunction and they met all our requirements,” said Nelson. "Therefore, we should be able to store everything we're collecting with significant margin."

Usually, the Odyssey team deletes the buffer after they send it along to the DSN. This time however, Nelson said, the plan is that the orbiter will dump the entire buffer at the end of conjunction. That combined with the ability to retransmit it, means "we're kind of betting on the come, so to speak, that much of the data is going to come down the first time," he explained. "We'll analyze it and it will give us the warm fuzzy that our rover is still doing just fine." Of course, if it's not there's not a lot they can do about it.

"We can't command," Nelson pointed out. "Well, we could command, we just don't dare command," he clarified. "You can drive your car off a cliff, the car doesn't care, but you don't dare." At this stage of the mission, no one is interested in taking a chance a command will go rogue and cause the rover to do some deleterious to itself.

While the Santa Maria data is just beginning to be analyzed and although the current plan calls for Opportunity to continue her work at this interestingly shaped 80-to-90-meter crater for a few sols after solar conjunction, it’s safe to say that this hole in the ground has been well worth the stop.

An impact into a homogeneous medium usually causes the ejecta to be hurled out in a fairly symmetrical pattern about the impact, with rays of ejecta coming out in vectors that point back toward the center. But in the images from orbit, the ejecta rays from Santa Maria are not pointing back toward the center of the crater.

“Santa Maria is something we rarely see if ever, a very fresh football size crater on fractured terrain,” said Arvidson. “Here, the ejecta rays are not symmetrical about the center point of the crater and now we're beginning to see why. When we look inside the crater from positions on the west and now on the southeast, we see that the rays seem to be coming from zones of weakness in the fractured terrain and the crater is not really circular – but it's kind of polygonal – so rather than an impact into homogenous media, what apparently happened is the impact hit on this highly fractured terrain and what's been thrown out of the crater was organized on the basis of those zones of weakness,” he explained.

“What's happening we think – and this is still a work in progress – is that the ejecta process is strongly influenced by these zones of weakness, these joints of fractures,” Arvidson underscored. “So the rays are not thrown out exactly from the center, but get reoriented as the process unfolds. We're seeing Nature’s way of dealing with hypervelocity impact onto fractured terrain, and this is an opportunity to infer the mechanics of hyper velocity impact into an isotropic or highly fractured material. That's the reason we're doing a lot of imaging of the area in addition to defining the stratigraphy or layers in the crater.”

Currently, Opportunity is parked over Luis de Torres, close to the top edge of Yuma. “It may be a small impact crater on the side of Santa Maria -- that's an interpretation,” said Arvidson. “The observation is that Yuma is a lower flat area that's inset into the rim, the wall rocks, so we're on the outer rim of that area.”

The solar conjunction slow down gives Opportunity a chance to conduct a long (multi-week) integration on Luis de Torres with the Mössbauer spectrometer to assess the types of minerals present in the target. The rover now has her Mössbauer down on the brushed spot on Luis de Torres and will continue those observations, along with its routine argon measurements through the solar conjunction period.

Mössbauer spectroscopy is a versatile technique that can give very precise information about the chemical, structural, magnetic and time-dependent properties of a material. Rudolph Mössbauer’s discovery of recoilless gamma ray emission and absorption in 1957, now referred to as the 'Mössbauer Effect', is what enabled the development of this technique. Mössbauer received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1961 for his work.

The rover's Mössbauer uses a small amount of radioactive cobalt-57 to elicit information from its target. With a half-life of less than a year, the cobalt has substantially depleted during Opportunity's seven years on Mars, so readings lasting days are necessary now to be equivalent to much shorter readings of a few hours during the primary mission.

Opportunity's power levels fluctuated from 585 to 555 watt-hours under hazier skies in January. It is spring in the southern hemisphere of Mars and dust is in the air, with atmospheric opacity or Tau elevated to 0.789. The rover managed to maintain a solar array dust factor of 0.603 however, meaning it is utilizing about 60% of the sunlight hitting its solar arrays. As January comes to an end and the rover heads into its eighth year of exploration, its total odometry is 26.66 kilometers (26,658.64 meters or 16.56 miles), nearly 45 times the 600 meters needed for "mission success."

Once solar conjunction is over, Opportunity will finish up the work at Santa Maria. “And then,” said Arvidson, "it's blasting across those plains the final 6000 meters (6 kilometers or 4 miles) to get to Cape York at Endeavour.”

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth