A.J.S. Rayl • Jan 31, 2010

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Rovers Pass 6-Year Milestone as Spirit Halts Extrication to Winter at Troy, Opportunity Cruises to Concepcion Crater

6 Earth years and still going

6 Earth years and still goingWhen they launched in the summer of 2003, Spirit and Opportunity were given 6 months at most to live. This month the twin robot field geologists both crossed the 6 Earth years milestone, a major, against-all-odds mission achievement.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

Five and a half years after they were supposed to be history, the Mars Exploration Rovers celebrated their sixth Earth year on the Red Planet with Opportunity pulling up to a fresh, new crater on the road to Endeavour, and Spirit working on repositioning itself to settle in for the coming Martian winter, and perhaps the rest of its mission.

Spirit arrived at Gusev Crater at 8:35 p.m. Pacific Standard Time (PST) January 3, 2004 as more than one billion people worldwide jammed online to “witness” the Internet’s biggest live event. Opportunity landed three weeks later on the plains of Meridiani Planum at 9:05 p.m. PST January 24, 2004, and millions more people cheered in countries everywhere. “They are emissaries not just of NASA or the United States, but the Earth,” Steve Squyres, MER principal investigator, of Cornell University, said then.

The rovers had flown into the Martian atmosphere and breezed through the six minutes of terror that followed, making it look easy and succeeding, against all odds, where most others before them had failed. Bouncing down onto the surface protected by airbags, they landed flawlessly and intact, Spirit upright and unscathed in amidst a jagged landscape, Opportunity rolling into a crater to score Earth’s first “300-million-mile hole-in-one.”

The twin robot field geologists got to work promptly seeking to fulfill the primary objective of finding evidence for past water on a mission designed to last for three months, and, if things went really well, six months max. After accomplishing their mission objective, Spirit and Opportunity both roved on and on and on.

Spirit navigated treacherous terrain to get to the Columbia Hills, where it then hiked to the two summits of Husband Hill, becoming the first Earth emissary to achieve such a feat. It then came down from the mountaintop to discover evidence of a steamy and violent environment on ancient Mars. Halfway around the planet, Opportunity focused first on Eagle Crater where it landed, then traveled more than 12 miles across the Meridiani plains. As it cruised from crater to crater, it uncovered evidence of a wet and acidic past environment, distinctly different from what its twin was finding.

For a total cost of $900 million to date, Spirit and Opportunity have given NASA and the country a legendary mission and perhaps the biggest bang for its exploration buck ever. They have given the world its first overland expedition of another planet beyond the Moon something you can't put a price on.

Neither the wicked cold of the Martian winters nor life-threatening dust storms, arthritic joints nor broken wheels has stopped them yet. Spirit and Opportunity have shown their robot right stuff every rove of the way, sending home stunning panoramas of a strangely familiar alien landscape along with discoveries that have expanded our knowledge about Mars. And they’re still taking Earthlings along vicariously for the ride, sharing their pictures and data in near real time with anyone and everyone in the world who has access to a computer and the Internet.

The solar-powered rovers’ big day -- January 24 when Opportunity joined Spirit in crossing the 6 Earth years milestone -- however, was eclipsed by a hastily assembled press teleconference. On January 26, NASA announced that Spirit was now a “stationary research platform,” because efforts to extricate it from the sand trap where it has been stuck for months had been unsuccessful.

Spirit still shining

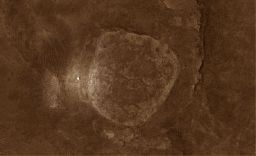

Spirit still shiningIn this picture of Home Plate, taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, the stark white figure to the left (west) of the geologic formation in this image enhanced by rover poet Stuart Atkinson is Spirit. "It's a screengrab from the excellent HiRISE IAS Viewer," he said. "I added some colour, then highlighted the position of Spirit. If you look carefully, you can actually see bright trailing leading to Spirit - this is the result of the (right front) broken wheel being dragged through the dirt, unearthing brighter material beneath." For more of Atkinson's enhanced images, poems, and thoughts, check out his "Road to Endeavour" at: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / enhancement by Stuart Atkinson

Spirit became embedded in the sandy soils of Troy last April as it was driving south along the western edge of the old circular volcanic plateau called Home Plate to get to its next destinations. Without warning, the wheels on its left side broke through a crusty surface and sunk into soft sand hidden underneath. Turns out, it was on the edge of a shallow sand-filled crater.

The MER team worked all last summer on a way to free Spirit. With a right front wheel that stopped working for good in 2006, this rover has been forced since then to do most of its roving backwards. Getting out of this sandy soil would be tricky business.

Team members, engineers and scientists alike, conducted extensive tests with ground rovers in a specially created sandbox in the indoor Mars yard at Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where the MERs were designed, built, and born. They also considered analysis, modeling, and input of members of review committees before choosing an exit strategy the rover began to put into motion last November. Spirit valiantly spun its wheels carrying out almost every command, but it made little progress and by early December 2009 its right rear wheel was deemed out of commission. That effectively turned the five-wheeled rover into a four-wheeled rover, making a difficult situation much worse.

Likening the rover’s predicament to “a golfer’s worst nightmare,” Doug McCuistion, director of the Mars Exploration Program at NASA Headquarters, told reporters that Spirit’s current location is probably “its final resting place.”

While it has been some time since NASA offered an official "status report” on the troubled rover, the timing of the announcement seemed off. MER fans and followers celebrating the rovers’ 6-year milestone ardently expressed their upset. To declare Spirit a stationary research platform seemed “premature.” It was downright unconscionable for some. “Many MER people are angry,” wrote one rover fan.

Spirit moved on. Even as it was being reassigned as a “stationary research platform," it was driving, backwards instead of forward as it had been, and it was making some progress. In fact, during the last couple of weeks, the rover has made more progress driving backwards than it had in all its forward exit drives.

"The vehicle has always driven backwards better than driving forward since it lost the use of its right front wheel," Chief MER Engineer, Jake Matijevic, a member of the MER design team, pointed out during an interview last Friday. “Moving backwards, we are retracing our steps and that has helped.”

Topographic map of Spirit's location at Troy

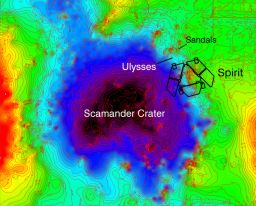

Topographic map of Spirit's location at TroyThis topographic map of Spirit's location at Troy represents low elevations in black, purple, and blue and high elevations in red. It was developed from the rover's camera images of the location, taken before it got mired in the sands of Ulysses at Troy. This model has had a regional slope removed, which reveals that Spirit's left wheels are sitting inside a subtle depression that the team has named Scamander Crater. The right-side wheels are outside the depression.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Ohio State University

Thus, while Spirit may now be deemed a stationary research platform, it’s a stationary research platform with, apparently, the right to and the capability of moving.

Although McCuistion had clarified that Spirit is “not dead,” but “has entered another phase of its long life,” the message delivered at the teleconference was confusing and funerary quips resounded in many of the headlines and stories that followed. Reporters not familiar with the mission interpreted the announcement as meaning Spirit was effectively dead in the sand, so to speak, that NASA was “abandoning” the rover as at least one major newspaper overseas bannered it, neither of which is true, all of which served to further muddle the message and misrepresent what is really happening.

What is true is there just isn’t enough time for Spirit to get out of the sand trap and get to a safe winter haven with only four working wheels. "We know we can't get out based on our current progress before winter sets in," rover driver Ashley Stroupe confirmed. That means Spirit has no choice but to stay right where it is and winter in place.

Because of its location on Mars, a little further south of the equator than Opportunity, Spirit has routinely hunkered down for the Martian winters, parking on a north-facing slope with its solar arrays angled toward the Sun for those most brutal of months. "We have always had to make Spirit a lander for the winter,” noted Ray Arvidson, deputy principal investigator, of Washington University St. Louis. “We planned several months ago that at a certain point, we would stop extrication attempts and settle down for winter.”

That “certain point” arrived this past month as Spirit suffered a fairly dramatic drop in energy. According to the latest predictions, by mid-February it probably won’t have enough power to drive and complete its other necessary engineering tasks. So, Plan B -- having the rover reposition itself to improve the tilt of its solar arrays and hang out in Troy for its fourth Martian winter -- was initiated. “The most important issue right now is surviving the winter,” said John Callas, MER project manager, of JPL. “It will all come down to temperature and how cold the rover electronics will get. Every bit of energy produced by Spirit’s solar arrays will go into keeping the rover’s critical electronics warm, either by having the electronics on or by turning on essential heaters.”

The winter Sun stays in the northern sky, so getting the solar arrays tilted as much as possible to the north would boost the amount of sunlight the rover could take in for power production. Since the MERs cannot mechanically adjust their arrays, they must move themselves to alter the angle. If Spirit were free roving, they would have it position itself between 0 and 5 degrees to the north. Currently, the rover is tilted at about 10-to-11 degrees south, so it’s got some serious maneuvering to do.

Simulation of Spirit's predicament

Simulation of Spirit's predicamentThis artistic image -- in which Astro0 has placed a two-dimensional MER into a scene created by pictures taken by the real rover -- illustrates Spirit's predicament at the location in Gusev Crater known as Troy. Although the angles are admittedly a little off and the disturbed soil isn't quite right, it offers the casual reader a glimpse into the present scene on Mars -- and this rover scribe thinks it's a pretty cool illustration.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / ©Astro0 2009

“We need to lift the rear of the rover, or the left side, or both,” said Stroupe. “Lifting the rear wheels out of their ruts by driving backward and slightly uphill will help. If necessary, we can try to lower the front right of the rover by attempting to drop the right-front wheel into a rut or dig it into a hole.”

Even a few degrees of improvement in the tilt though could make enough difference to enable Spirit to communicate at least every few days through winter and avoid hibernation, Matijevic pointed out. But there are many factors at play. “Spirit’s survival depends on the amount of dust in the air and on the solar panels, the temperature on Mars, exactly the attitude the rover ends up," Stroupe added. "All these factors will have a big effect on how much energy the rover has and that makes it a little hard to predict exactly what's going to happen.”

If Spirit does not get its solar arrays positioned in a more northerly tilt, it’s still possible it can survive this winter. At the current rate of dust accumulation, solar arrays at zero tilt would provide “barely enough energy to run the survival heaters through the Mars winter solstice,” May 15, 2010, Jennifer Herman, a rover power engineer at JPL, said in late December. However, it’s looking more probable now that if the rover it doesn’t improve its current tilt, which has degraded this month, it will drain its main power batteries and trip a low-power fault. If it trips the fault, Spirit would shut itself down and enter a kind of hibernation mode -- “sort of like a polar bear,” said Callas -- where communications with the MER team on Earth would be cut off. It would likely stay in that hibernating mode until spring, perhaps even summer when the Sun could beam enough photon power down to its arrays to bring it out of its slumber.

"The rovers shut down every night," Callas reminded reporters during the teleconference. If, however, something breaks during that time or Mars brings something untoward the rover’s way, it could be the end. Therein lies the real concern: Spirit has been close to death many times before, just never this close.

"Our primary focus in the time we have remaining is to try and continue to improve that northerly tilt to maximize our chances of still having our rover to operate come springtime," Squyres said late last week.

Ulysses in Troy

Ulysses in TroySpirit accidentally slipped through a patch of ground in an area the team calls Troy back in April. Inside the area, the rover churned up a mixture of light-toned soils unlike anything either rover has seen. The variations in this mixture, now called Ulysses, are revealed in pastel hues visible in this panoramic camera (Pancam)image, which has been stretched to emphasize the differences. The rover used its Pancam on its Sol 1892(Apr. 29, 2009) to take the three images combined into this composite image. The three images were taken through filters centered at wavelengths of 750 nanometers, 530 nanometers and 430 nanometers. Spirit became embedded here about a week later. The two rocks near the upper right corner of this view are each about 10 centimeters (4 inches) long and 2 to 3 centimeters (1 inch) wide. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell University

Once the Martian winter solstice has passed and winter gives way to spring, the plan calls for Spirit to continue conducting its winter science campaign from its embedded position at Troy. From a stationary state, Spirit can still return textbook changing scientific research. “There’s a class of science we can do only with a stationary vehicle, science that we had put off during the years of driving,” Squyres explained. “Degraded mobility lets us transition to stationary science.”

This winter’s science campaign focuses on three different science experiments, as reported in the December 2009 MER Update, and officially announced by Squyres at the teleconference.

“The soils where Spirit is are very complex and the rover can study and further characterize variations in the composition of nearby patches that have been affected by water, as well as watch how wind moves soil particles,” Arvidson recounted. “During the winter science campaign the rover will also continue a long-term study of the atmosphere and do a radio science study to record the wobble in the planet's axis of rotation, something that can’t be done with a mobile rover and something that will give us insight about the planet’s core.”

Long-term change in the spin direction of Mars’ axis would inform scientists about the diameter and density of the planet's core, according to William Folkner of JPL, who has been patiently waiting the entire mission to do this research. "Short-period changes could tell us whether the core is liquid or solid," he said. And that is big deal planetary science.

“It will take months of radio-tracking the motion of a point on the surface of Mars to calculate the long-term motion of Mars’ orbit to an accuracy of a few inches. This would be something so different from the other knowledge we’ve gained from Spirit,” said Squyres. "If the final feather in Spirits cap scientifically were that we were able to measure definitively that the core of Mars was liquid or solid," he added “that would be a wonderful way to wrap up the mission.” Indeed, determining whether Mars' core is liquid or solid would be a huge achievement for a rover that has already accomplished far more than anyone ever dreamed possible.

Although there is no disagreement that Spirit is slowing down, its roving days may not be entirely over and many team members are keeping hope alive. Sure, it would take a miracle for this rover to exit the sands of Ulysses in Troy and rove on any significant distance with just four wheels working. Everyone knows that. "I don't think we'll ever get to Goddard and von Braun now, but we can possibly make it to other targets tens of meters away,” Arvidson said. “If we finish the science we want to do where we are now, there is no reason why we might not try to creep along to the next most interesting place is and see if we make it," added Stroupe.

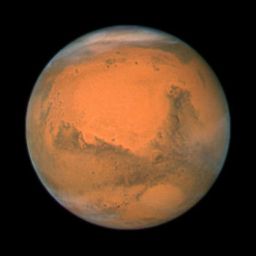

Mars

MarsNASA's Hubble Space Telescope took this close-up of Mars when it was just 88 million kilometers – 55 million miles – away. This color image was assembled from a series of exposures taken with the Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 within 36 hours of the planet's closest approach on December 18, 2007 . Mars and Earth have a "close encounter" about every 26 months. These periodic encounters are due to the differences in the two planets' orbits. Credit: NASA, ESA, Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA), J. Bell (Cornell), and M. Wolff (SSI, Boulder)

On the other side of Mars, Opportunity finished its study of the magnificent rock called Marquette Island. It had been checking this gem out since last November and studies of texture and composition confirmed that this rock, not much bigger than a basketball, originated deep inside the Martian crust, making every minute the rover spent there worth it. The MER scientists think that a crater-digging impact probably excavated the rock and hurled it a long distance, to the place where Opportunity found it along it long trek across the Meridiani plains.

In mid-January, its work at Marquette was finally complete and Opportunity took off, roving ever onward to Endeavour, still 12 kilometers (7.4 miles) away. After crossing its 6 Earth-year milestone, it pressed on, knocking off one drive after another, wrapping the month with a crater stop at a hole in the ground dubbed Concepcion. "It really is the best look anyone has ever had of a fresh crater on Mars,” said Squyres. “Geologically this thing formed yesterday and … that's pretty neat. We haven't seen anything like this.”

All in all, January 2010 – the 73rd month of the MERs 3-month tour – was "a very memorable month," concluded Squyres. As February sets in, optimism is tempered, but Spirit is alive and doing well all things considered and no one on this team is composing Spirit’s obituary yet. “I don't think I'm ready to write off this particular phase of my career,” said Matijevic. “I can't think of this situation right now as anything other than another problem that has to be solved."

"We are not giving up on Spirit," Squyres underscored. “And I mean that.”

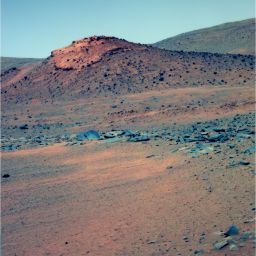

Concepcion Crater

Concepcion CraterOpportunity has just arrived at Concepcion Crater, the youngest and "freshest" crater found on the MER mission. It took this image with its Pancam and MER aficionado Stuart Atkinson added the color. Check out his "Road to Endeavour" blog at: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / color by Stuart Atkinson

In other Mars news, the Red Planet made one of its regular "close encounters" with Earth this month. On January 27th, Mars was just 99 million kilometers away and looking bigger through a telescope than at any time between 2008 and 2014. The planet's 14-arcsecond diameter remains essentially unchanged for a few more days so grab your telescope or find an observatory while the viewing is still good. A couple of rovers are waiting for you.

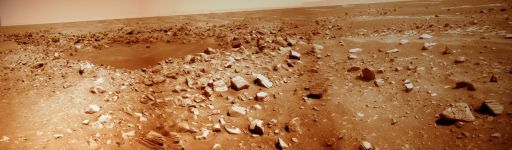

Spirit from Gusev Crater

January 2010 began on a high note for Spirit. Although it was still embedded in the sands of Ulysses at Troy and moving only millimeters, it crossed its 6 Earth year finish line on January 3. Unfortunately, the month went downhill from there.

Spirt near Troy one year ago

Spirt near Troy one year agoYou can see Spirit in the upper right quadrant of this image about this time last year by the HiRISE camera onboard MRO. The rover is at about 2 o'clock, appearing almost as if it's in Mars' spotlight. If you look closely, you'll see its form and head, and even the trail it plowed by dragging its broken right front wheel.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / enhancement by Stuart Atkinson

Spirit’s attempts to extricate itself this month were complicated by the lack of functionality in both the right-front wheel, broken since 2006, and the right-rear wheel, which stopped working on Sol 2099 (November 28, 2009). Surprisingly, Spirit’s right-front wheel did show some movement around the same time the right rear wheel was faltering, but it was short-lived and has not rotated usefully since Sol 2117 (December 16, 2009) and at the end of the sol, this rover was left with only four fully operational wheels.

On Sol 2132 (January 1, 2010), Spirit, facing northward, steered its left-front, left-rear, and right-rear wheels to 60 degrees, to toe-in in an attempt to get the sandy material in front of the wheels to collapse into the trenches in which the wheels are embedded. The rover was to then steer its wheels back to straightforward, using the flat outer surface of the wheel to push the previously collapsed material to the side of the wheel in order to provide some space in front of each wheel into which it could move. The drive, which was to have included four 2.5-meter (8.2-foot) forward drive steps, was terminated during the initial steering of the wheels because the rover [flight software] thought the left-rear steering motor had stalled. In fact, the left-rear wheel was continuing to steer but resistance from the surrounding soil had slowed it to a rate such that the flight software did not detect its motion.

Spirit and the team picked up on Sol 2136 (January 5, 2010) where the Sol 2132 drive stopped. The rover straightened its left-front, left-rear, and right-rear wheels, then proceeded with four 2.5-meter (8.2-foot) drive steps, followed by turning the right-front wheel inward 60 degrees. While another four 2.5-meter (8.2-foot) drive steps had been commanded, the drive stopped automatically when the onboard sinkage measurement exceeded 1 centimeter (0.4 inch). Nevertheless, this drive did achieve 2.28 centimeters (0.9 inch) of forward progress.

Nose to the sand trap, Spirit tried more extrication drives on Sols 2138, 2140 and 2142 (January 7, 9 and 11, 2010), during which it employed another technique – steering the wheels back and forth – or “wiggling” them – before driving. This little trick can actually sweep material out of the wheel tracks and allow fresh material to slough off the leading trench face and provide traction under the wheel. The rover also tried some slower wheel speeds on two of the drives. But even with these new techniques, Spirit achieved negligible progress, and it continued to sink deeper into the sand trap with each attempt.

On January 13, JPL issued notice that the list of remaining maneuvers being considered for extricating Spirit was becoming shorter. The team carried on, following the strategy it developed last summer. While the engineers had considered using Spirit's robotic arm to sculpt the ground directly in front of the left-front wheel, the only working wheel the arm can reach, they opted instead to simply have Spirit begin driving backwards.

Extrication frustration

Extrication frustrationThis animation is composed of 21 right-front hazard avoidance camera images that Spirit took from Sols 2078 to 2138. The camera has a wide "fish-eye" field of view that can see the workspace in front of the rover, between the two front wheels, all the way to the horizon and Husband Hill in the background. Download the animation at full resolution in Quicktime format (3.5 MB)Credit: NASA / JPL / animation by Emily Lakdawalla

Complicating the situation, the amount of energy that Spirit was able to produce began to decline significantly as autumn shortened the days in the southern hemisphere of Mars where the rovers are. “We were running out of time,” said rover driver Ashley Stroupe.

Because of its location in Gusev Crater, 14.6 degrees south, 175.5 degrees east, Spirit has always had to perch on a northerly slope where it could angle its solar arrays to the Sun to survive the harsh Martian winters. Tilting itself and its solar arrays toward the north allows the rover to take in more sunshine fuel. Even if Spirit managed to pop out of its predicament at this point, it wouldn’t be able to go very far with only four of its six wheels working, so by mid-January extrication attempts turned into repositioning maneuvers to prepare for the coming winter.

On Sol 2145 (January 14, 2010), Spirit turned wheels again, driving backwards this time and wiggling the wheels before performing each drive step. Beyond providing a bit more traction, wheel wiggling causes the flat surface of the wheel side (hub) to kick against the loose material like a swimmer's frog kick or breaststroke to provide motive force. "In a sense, steering the wheels back and forth – the wheel wiggles – is sort of like doing a little preparing of the way before moving," explained Jake Matijevic, chief rover engineer. "It kind of breaks up the terrain in front of the rear wheels and the forward motion of the wheel is the area that has sort of been prepared. It's a little bit like plowing the terrain in front of you before moving forward, that kind of effect."

Spirit was commanded to execute enough wheel rotations to move itself backward about 30 meters (98 feet) in six steps of 5 meters (16 feet) each, if, that is, it were in a situation with good traction. Since the rover is embedded in sandy soils though it only moved backward a total of a little more than 3 centimeters (1.2 inches). But it raised itself in altitude just more than 1 centimeter (0.4 inch), marking the first time the rover had climbed from its sunken position since extrication attempts began. In addition, the drive -- because the rover's rear wheels were climbing and the back of the rover rose -- improved the rover’s approximately 11-degree south tilt by a little more than one degree, which was confirmed by images from the rear hazard avoidance camera.

Repeating the same drive command on Sol 2047 (January 16, 2010), Spirit moved another 3.5 centimeters (1.4 inches) backward and climbed another 0.3 centimeters (0.1 inch). This time however the rover yawed counterclockwise, swinging the angled solar arrays away from north causing the recent gain in northern tilt to be lost. Nevertheless, the rear wheels continued to climb, suggesting that the middle wheels are gaining traction, Jake Matijevic, chief rover engineer, pointed out. Moreover, in just two backwards drives, Spirit covered the entire distance achieved with forward driving and then some. Given that it’s only got four wheels, the rover’s movement was nothing less than impressive, yet another example of the mettle of this little robot field geologist. Understandably, team was happy with those results.

Taking it backwards

Taking it backwardsThis two-frame animation, is created from two wide-angle pictures that Spirit took this month shown one after the other. The rover took the images with its rear hazard-avoidance camera: one at the end of the previous drive two sols earlier and then after the Sol 2147 (Jan. 16, 2010) drive. Visible changes from the first to the second as a result of the rover's motion, include the landscape appearing to shift to the right and the forground rocks near the bottom of the image appearing to come closer. The view is to the south, looking at and beyond Spirit's rear wheels, with the bottom surface of a solar panel at the top of the image. Spirit moved about 3.5 centimeters (1.4 inches) southward and yawed slightly counterclockwise.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

On Sol 2050 (January 19, 2010), Spirit revved up again for another backwards drive, but this time its left middle wheel stalled, which sent the engineers back into huddles. "In the diagnostic, we rotate the wheels and make sure the motor is working properly and then try to figure out, as we did when stalled at other times during driving in this area, if it is simply terrain dependent,” informed Matijevic. “The diagnostic on the following sol seemed to provide that for us. There was nothing wrong with the wheel.”

Spirit kept at it. On Sol 2152 (January 21, 2010), it achieved another 4 centimeters (1.57 inches) of "effective backward motion," as Matijevic put it, after turning its wheels for 23 meters. Two sols later, it made another 8 centimeters (about 3.15 inches) worth of progress from a commanded 60 meters of driving. But on Sol 2156 (January 25, 2010), it moved 2 centimeters (.78 inch) after some 50 meters of effective wheel turning, and just 2 more centimeters on Sol 2158 (January 27, 2010) after 84 meters of turning its wheels. Although progress was uneven, it was meaningful progress. “This is a high slip region where there is quite a bit of impediment," reminded Matijevic.

Spirit was slated to drive on 2161 (January 30, 2010) but the results were not available by presstime. The latest data clearly indicate the tilt to the north has degraded or gotten worse. "Before we started driving backwards, we were roughly at 4 degrees southerly tilt. Now, we're roughly in about 10 degrees southerly tilt," Matijevic informed last Friday. But this was expected and should be temporary.

"The strategy we have for Spirit getting the tilt better [takes us] through a couple of days of it getting worse before a turn around," Stroupe explained.

The ideal and best tilt they could hope for Spirit to achieve is about 5 degrees north; hence, the rover is going to have to make up for lost tilt as well as gain new tilt. “We're going to keep doing some maneuvering,” said Stroupe. “We've got a few tricks we're still discussing to figure out how to help it out as best we can."

One of those tricks is to drive about a half meter (about 1.6 feet) backwards with the intention of getting the front wheels to fall into the trench Spirit dug up with the middle wheels while trying to drive forward. “The idea here is to create a bias of the vehicle in pitch, so that we would effectively move the array more toward northerly direction,” explained Matijevic. “A few degrees of improvement here could make a big difference in terms of what our array performance might be like over the next few months.” As January comes to a close, Spirit is “about halfway along" toward that goal, he said.

Moving on

Moving onAfter being declared a stationary research platform, Spirit moved on last week. The rover took the pictures for this animation with its front hazard-avoidance camera during five drives from Sols 2145-2154 (Jan. 14-23, 2010). The view is toward the north, looking down at the rover's front wheels.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

There is still a chance that Spirit could make it through the winter even without an improved tilt. “Right now it is not a zero chance of survivability,” Stroupe said.

Spirit would need to maintain a power level of about 160 watt-hours to be able to carry out minimal tasks, as MER Project Manager John Callas said in the December 2009 MER Update. "We were projecting that for the Martian winter solstice [May 15, 2010] -- and it breaks out to about 40 watt hours of battery heating on top of about 120 watt hours to just maintain the rover’s basic power system capability – to get up, check in,” Matijevic expounded.

Spirit however suffered a pretty rapid drop in energy this month, with power levels falling from a high of around 243 watt-hours to about 180 at January's end. If its power drops below 160 watt-hours, it will begin draining its batteries and trip the low-power fault that will put it in a hibernation mode, until the spring or summer Sun can replenish its energy.

In that low-power fault or hibernation mode, Spirit is supposed to wake up once a sol, check its battery state of charge and, if it's above a certain level, try to call home. If it doesn’t have enough energy, “it hits the snooze button and checks the next day,” offered Stroupe.

Moving on

Moving onThis animation shows Spirit's movement from as a result of five drives from Sols 2145-2154 (Jan. 14-23, 2010). The rover took these images that went into it with its rear hazard-avoidance camera. The view is toward the south, looking down at the rover's rear wheels.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

The fault has only been tripped once before on the mission, by Spirit way back on Sol 18, when it got stuck in a reboot loop and was constantly awake and draining battery. “But it wasn't a continual state,” Stroupe said. “This time it could be in that low-power fault state for an extended period of time and we would basically be completely out of touch with the rover.”

"It means we won't be getting downlinks and we won't be able to command Spirit,” Matijevic elaborated. “We’ll effectively be letting the vehicle take care of itself.” Sounds seamless enough, thinking back on the scene where C3PO shuts down in StarWars. But we’re talking about Mars and an aging robot that has endured thousands of intense thermal cyclings, temperate changes that vary 100 degrees C a sol, it’s metal parts expanding and contracting dramatically every rise and every fall. “The danger here is that when you're in a situation like this and you can no longer talk with it and it doesn’t have the ability to talk back to you, you are losing context one day to the next,” he explained. “Time drifts, performance changes, all kinds of things might take place that you are essentially blind to. So it becomes a difficult business of predicting how well you will be able to interact with it once winter is over and you get a chance to do so."

If current power projections are anywhere near correct, it’s possible the rover will be incommunicado as long as six months, Squyes said. Not surprisingly, concern is growing.

At the same time, low-power fault mode exists for “exactly these conditions” and it is intended to protect the vehicle. “Spirit will do the very best it can to keep itself alive through winter,” assured Squyres. “Whether or not it can succeed after all the abuse heaped on it over the years, it's just impossible to predict, but we are going to do everything we can to help the rover.”

The team’s greatest concern and deepest fear lies within that fault trip. Spirit could go into low-power fault mode sometime over the winter and “something bad,” as Squyres puts it, could happen and the team could be greeted come spring with nothing but the deathly chill of Martian silence. No beep. No nothing. “We voided the warranty on this thing a very long time ago, and there are no guarantees. We could never hear from the vehicle again,” said Squyres. “Spirit is in a very tough location right now. This is going to be by far the hardest winter that we've ever been through.”

So close yet so far

So close yet so farSpirit snapped this picture of von Braun on its Sol 2114 (Dec. 13, 2009) with its panoramic camera (Pancam). The rover and its team had hoped to have gotten to this geologic formation long ago, but 2009 proved to be a year of challenged mobility for this rover. The rover remains embedded in the sands of Ulysses at Troy, where it has been since last April with this view of its elusive next-big-destination.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell University

But this is Spirit. If any rover can do it, this one will. As the MER team sees things now, it has a job to do and that’s where the hearts and minds are. Squyres has said many times how this team excels when confronted with a problem. Of course, like humans, the day will come when these robots die. But there’s a sense among the team members that this is not this rover’s time. "We have to hunker down for the winter, so we are a lander starting in a couple of weeks and at least for the next six months, and then we will reevaluate the extent to which we can get out in the ensuing spring," said Arvidson. “If we can't, there's still good science to do – with the radio science, the monitoring of the weather, and also new [soil patches] to study, to characterize the sulfates.”

The science story from Home Plate actually is really coming together. "It looks like after the hydrothermal activity was finished and you had some of those sulfates sitting with basalt they have really been reprocessed by subsequent water and it’s most likely associated with snow, when Mars spin axis gets a little higher and the ice at the high latitudes winds up as snow at the equator. A little bit of snowmelt is reworking the sulfates, providing corrosion of the salt and evidence locally within tens of meters for what water has been doing over the recent geologic time there,” Arvidson summed up. “And there's still a lot to explore."

While it might seem that Spirit’s restriction to the immediate area promises something for the scientists but little to nothing for the rover drivers and engineers, think again. "We really are a team,” said Stroupe. “As engineers, we’re here for the science. So even though we'd like to be achieving that science by going to new places, we still feel really proud of the fact that we're supporting the best science we can do on Mars with this vehicle. And, in some ways these smaller, 20 centimeters drives are more challenging and more interesting to sequence. Trying to get this semi-crippled rover to do what we want it to do isn’t going to be easy. In fact, the next two weeks are probably going to be the most challenging we've ever had driving this rover.”

That kind of mutual respect and one-for-all work ethic are rampant among this team and their two robot field geologist colleagues and they are, arguably, what has led to more than 90 scientific papers, 400 abstracts, hundreds of thousands of brilliantly crisp photographs of a planet we humans may someday call home, and to the MER mission becoming not only a legend in its own time but a model in the big book on space exploration.

Spirit at Home

Spirit at HomeThe HiRISE camera on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter took this image of Spirit at Home on July 16, 2009. The rover is at lower left, on the west side of Home Plate.Credit: NASA / JPL / UA

Spirit heads into its seventh year of exploration facing more uncertainties than it has ever faced before. But one thing that is certain is this team is standing by its rover. "We are not giving up on Spirit," Squyres reiterated. Still, he acknowledges all possibilities and is keenly aware of what challenges lie ahead.

"With 4 wheels active and 2 wheels dead, and buried almost up to its belly in sand, it's very unlikely Spirit is going to move any substantial distance from its current location. This thing isn’t going to climb to the summit of McCool Hill,” he said ruefully. But in recent weeks, the rover has made progress and if come spring it is able and willing perhaps it can bring in new terrain within reach.

“We will do everything that we can to use the mobility system on the vehicle to benefit the science in every way possible,” Squyres said. “We are going to continue to do everything we possibly can with this rover once winter's over and we'll see what we get. If the rover popped out and scooted across the countryside, so be it, that's would be great. But nobody's expecting that to happen. What we're expecting is small motion, and if that's all we get, we can do a lot of good science for a long time."

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

As January dawned at Meridiani Planum, Opportunity was still examining the rock known as Marquette Island. It used its rock abrasion tool (RAT) to grind a 1.5-millimeter-deep (0.06-inch-deep) hole in the hard rock at a target dubbed Peck Bay 2. But when it did an alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) analysis of that target, it was significantly different than the pre-grind analysis, so the team decided the rover would spend another week at Marquette Island to try so it could try and figure out why.

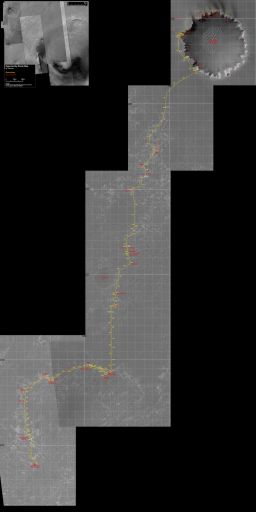

Opportunity route map

Opportunity route mapThis mosaic of images taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter as been annotated by MER aficionado Eduardo Tesheiner to show Opportunity's path from Victoria Crater toward Endeavour Crater, up to its Sol 2138 (Jan. 28, 2010).Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / MSSS / annotated by Eduardo Tesheiner

The rover brushed the newly RAT-ed hole to clear out the cuttings left by the grind, then rover used its microscopic imager (MI) to take pictures to confirm the job was done. Opportunity then continued to try and tease out is composition by taking APXS measurements of Peck Bay 2 at different positions.

“It was very interesting,” said Squyres. “There were some significant changes in the chemistry, which means grinding into it was the right thing to do. It's a little more complicated story than I would like it to be. That’s because the rover didn't grind as deeply as the team really would have liked it to. “We would have liked to blast right into it, making a 5,6,7-millmeter grind to put a deep RAT hole where you would blow any weathering layer across the entire RAT hole and put on the APXS and get one good measurement. The problem is we don't know how much grind capability we’ve got left and we think it's not much. Moreover, it turned out we were correct that Marquette Island is an extremely hard rock and a good hard grind could have taken the instrument out completely.”

The team commanded Opportunity to do a shallow grind and go as deeply as possible based on its “incomplete knowledge” of how much RAT the rover has left. Then the rover would take several different measurements at different parts of the RAT hole. “You assume you're seeing a mixture of surface and subsurface material in different proportions depending on where you're measuring. So, by taking multiple measurements and connecting a line between them you can both interpolate and extrapolate and learn quite a bit about what the composition of the individual end members are, especially since we know what the surface material looks like already,” Squyres explained. “We did that and are in the process of doing the calculations.”

Opportunity spent Sols 2118 to 2121 (January 7-11, 2010) completing the two-month-long investigation of Marquette Island with its APXS and MI. [Note: No sol number corresponds to January 8 because no noon at Opportunity's location fell during that date's 24 hours PST.]

Intriguingly, Squyres pointed out, neither the surface composition nor the interior composition was a “perfect match” to the “protolith” for the Meridiani sediments. “We’re still working it out, but it was darn good thing that we took the chance and used the RAT on Marquette, because it has revealed some significant variations."

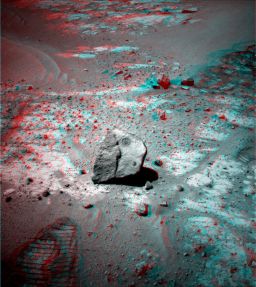

Marquette Island in 3-D

Opportunity took this image of Marquette Island -- one of the most interesting rocks it's found to date, according to Steve Squyres -- with its panoramic camera (Pancam) in early January 2010. You can clearly see the circular spot where the rover used its rock abrasion tool (RAT) to grind into the surface. Marquette is now and forever will be a MER branded stone.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / 3-D by Stuart Atkinson

The variations along with the on-going compositional analysis do bear out the MER scientists’ hypothesis that Marquette Island is an ancient hunk of rock hurled up to the surface by some major impact.

"Anytime you see some kind of variational depth in a rock like this, you interpret it to mean there is some kind of chemical alteration that has taken place since the rock was first exposed on the surface,” Squyres explained. “That is what we interpret it to mean here. This is the first time we have seen altered basalt at the Meridiani site, and so we want to proceed thoughtfully as we try to work out exactly what [all the data returned] means. “There is some complex geochemistry we still have to work through.”

With its work at Marquette finally done, Opportunity headed out on Sol 2122 (January 12, 2010), driving away from Marquette Island with a 25.69-meter (84.28-foot) jaunt on. After that, it was full steam ahead.

The rover drove again the following three sols, for 44.9 meters (147.3 feet), 47.68 meters (156.4 feet), and 37.97 (124.5) meters respectively. In the midst, its odometer clicked to 19 kilometers (11.8 miles) on Sol 2124, (January 14, 2010), something that the drivers acknowledged with reverance.

After a two-sol break from driving, Opportunity hit the Meridiani highway again on Sol 2128 (January 18, 2010) logging 61.37 meters (201.3 feet). It followed that drive with an impressive 70.95-meter (232.78-foot) sprint on Sol 2130 (January 20, 2010), for a total of more than 170 meters (about 558 feet) on those two drives. That put the rover about 100 meters (328 feet) away from its next intermediate target, a geologically young impact crater dubbed Conception.

During the past week and a half, Opportunity moved in, driving for 19.84 meters (about 65 feet) on Sol 2131 (January 21, 2010) and 27.73 meters (90.9 feet) on Sol 2133 (January 23, 2010) before taking a three-sol break as temperatures and power production dropped. Opportunity ‘fired its engines’ again on Sol 2136 (January 26, 2010) and ripped off a 39.1-meter (128.2-foot) drive up toward Concepcion's rim, followed by a careful 11.63-meter (38.1-foot) rove on Sol 2138 (January 28, 2010).

The right-front wheel currents -- which last year began drawing more current than the others -- have been “well-behaved,” as the rover engineers describe it. "But we try to baby it a little bit by mostly driving backwards or bogie first, to insure that most of the work is done by the rear and middle wheels rather than the front wheels,” Matijevic said. “When we see the high current start to peak up somewhat – usually after we have done a few weeks of driving – then we start looking around for a target of interest to the scientists."

Welcome to Concepcion Crater. Opportunity’s plan for the next couple of weeks is to drive as far around the 10-meter (33-foot) diameter crater as possible, taking pictures all along the way. "We are treating with lot of respect – it is somewhat difficult area to work in," said Squyres. "To the west there appears to be more of these fairly large dune forms that it's been trying to avoid and we haven't mapped the eastern portion yet," Matijevic added.

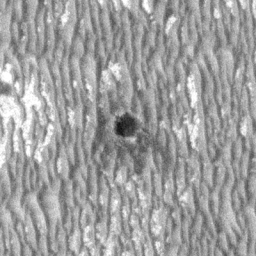

Concepcion crater from HiRISE

Concepcion crater from HiRISEConcepcion crater is relatively fresh, because it still retains dark rays superimposed upon the Meridiani dunes. However, it is not as fresh as some craters in Meridiani, because it lacks bright rays. It is estimated to be roughly 1,000 years old. Opportunity approached it on sol 2,138. The image covers an area 100 meters square.

Credit: NASA / JPL / University of Arizona

Concepcion has the scientists especially excited. "This is by far freshest crater on Mars and probably freshest either rover will ever see, surrounded by very fresh ejecta,” Squyres explained. “You can see the ejecta [rocks] lying on top of the ripples. So the crater formed after the most recent most significant motion of the ripples and that means this is a very young crater.”

This baby actually is estimated to be about 1,000 years old, making it the youngest crater explored on the mission. Being young, it’s “very blocky, very rugged,” said Squyres. “And we're going to tiptoe around this thing pretty very carefully because it is a real rubble pile.”

As January turns to February, Opportunity is sporting some 19,314 kilometers (12 miles) on its odometer. But the Martian winter is also beginning to impact this rover. "Opportunity is also a little bit energy-limited for its mission", said Matijevic. “Its power levels dropped from a high of 336 watt-hours earlier this month to "about 290 watt-hours" as the weekend began. The team expects this rover’s power production to remain "in the 250 regimes” for most of the next couple of months," he added. "It will drive as far as it can on any given day, basically drive down the batteries and recharge them the next day, so you should see a pattern of where we drive every other day at best.”

There is some good news though. "The winter season is a kind of quiet season for storms in the area and you usually see the tau [amount of dust in the skies overhead] to fluctuate between .4 and .3 [hazy to slightly hazier] at both sites during these winter months,” Maitjevic noted.

Of course, one instrument that would actually benefit from a little, well-aimed gust of wind or two is the dust-obscured miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES). The rover continued throughout January to open the elevation mirror shroud on its mineral-detecting instrument when appropriate, in hopes Mars will one sol whisk it clean, but no wind or dust clearance has occurred yet.

It’s been about 15 months now since Opportunity set out from Victoria Crater on what is an 18-kilometer journey to Endeavour Crater. To date, it has put 6 of those kilometers on its odometer, with 12 more to go. "We're about one-third of the way there,” said Matijevic. “It will probably take at least another year before we’re reasonably close. But 6 kilometers since we left Victoria, that's pretty good for this vehicle."

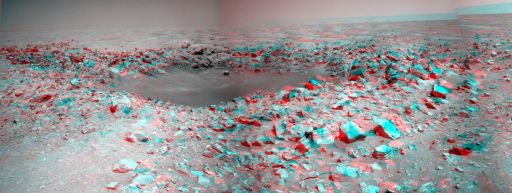

Concepcion in 3-D

Concepcion in 3-DStill got your 3-D glasses from the Grammys last Night? Check this out. On its approach to Concepcion Opportunity used its Pancam to take this image. MER aficionado Stuart Atkinson rendered it in 3-D. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / 3-D by S.Atkinson

Check out Atkinson's "Road to Endeavour" blog at: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth