A.J.S. Rayl • Jan 31, 2006

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Spirit Heads to Home Plate as Opportunity Finally Roves On

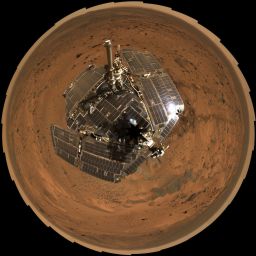

A bird's eye view of Spirit

A bird's eye view of SpiritThis bird's-eye view combines a self-portrait of Spirit's deck and a panoramic mosaic of the Martian surface as viewed by the rover. The rover's solar panels are still gleaming in the sunlight, having acquired only a thin veneer of dust two years after the rover landed and commenced exploring the red planet. Spirit captured this 360-degree panorama on the summit of Husband Hill inside Mars' Gusev Crater. During the period from Spirit's Martian days, or sols, 583 to 586 (Aug. 24 to 27, 2005), the rover's panoramic camera acquired the hundreds of individual frames for this largest panorama ever photographed by Spirit. This image is an approximately true-color rendering presented with geometric seam correction.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

As the Mars Exploration Rover mission presses onward into its third Earth year -- and second Mars year -- the twin robot field geologists are moving to new destinations.

Spirit continued her hike down Husband Hill toward Home Plate and the Inner Basin of Gusev Crater this month, checking out bedrock, interesting soil patches, and rippled sand dunes along the way. She spent the New Year’s weekend finishing work on the rippled dune field dubbed El Dorado, with plans to “sprint” for the rest of the month into the Inner Basin to a target known as Home Plate, as lead rover scientist Steve Squyres put it. Along the way, however, she churned up one of the mission’s most interesting finds -- intriguing white soil at a target called Arad -- and had to stop to investigate. The spot turned out to be the saltiest place found to date on Mars and another clue to the existence of past water at Gusev.

On the other side of the planet, Opportunity finally got back to moving after suffering a “broken arm” late in November that left her at a standstill at the Olympia outcrop in Meridiani Planum until about a week and a half ago. Since then, she has been repositioning herself to take microscopic images of various targets in the layered rocks of Olympia that feature “festoons,” distinctive centimeter-sized, smile-shaped features that are a sign of past water. The rover also spent time conducting atmospheric and mini thermal emission spectrometer (mini-TES) observations as engineers continued to test and evaluate the best place for the rover to put her arm so she could resume driving. Once Opportunity was given the green light to begin moving again, she immediately repositioned herself in front of a rock festoon-rich rock dubbed Overgaard, where she has been examining several chosen spots up close.

Both Spirit and Opportunity are in good health now, but winter is coming on and the power is beginning to drop. The rovers have already survived one Martian winter, so the team is prepared. But they also know the rovers cannot go on forever. “We’re living day to day at this point,” Squyres told The Planetary Society in an interview. “We think we’ve got a fighting chance to get both rovers through the winter, but it’s going to be hard work, just like it was last year. We have two rovers that are getting very old and we have no basis for knowing how long they will survive. We continue to generate plans for them that extend into the distant future, but each day we try to drive them like no tomorrow.”

Spirit from Gusev Crater

As the calendar flipped over to 2006, Spirit welcomed the New Year by taking a striking panorama of the El Dorado dune field and completing “a very quick, very aggressive, very successful” IDD campaign there, said Squyres. During the holiday weekend, the rover used all three of her spectrometers plus the microscopic imager (MI) and the panorama camera (PanCam) to check out a target there called Edgar, and to acquire spectral data and compositional and mineralogical information about these large, rippled sand deposits.

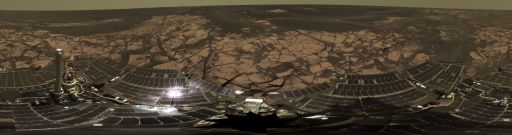

Spirit descends Husband Hill

Spirit descends Husband HillIn late November, while descending Husband Hill, Spirit took this image whilestopped at Seminole, one in a series of bedrock-laden terraces. It is themost detailed panorama so far of the Inner Basin, which she must cross toget to McCool Hill, her next major destination. The rover acquired the 405individual images that make up this 360-degree view of the surrounding terrainusing five different filters on the PanCam from Sols 672 to 677 (November23 to 28), the Thanksgiving holiday weekend. This image is an approximatelytrue-color rendering using camera's 750-, 530-, and 430-nanometer filters.Seams between individual frames have been eliminated from the sky portion ofthe mosaic to better simulate the vista a person standing on Mars would see.

Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell

Following her study of El Dorado, driving became the primary objective on Spirit’s agenda. The team wants Spirit to get to Home Plate, a conspicuous circular feature visible from space and from the summit of Husband Hill, and then rove on to McCool Hill where she can position herself for the best possible sunlight exposure on the north-facing slopes during the Martian winter. Therefore, the team planned major roves during the first week of January in an effort to maximize driving, because on Sol 715 (January 6), the rover went into restricted sols, and that meant she would not be able to drive every day for the ensuing week or so. (Restricted sols occur when the timing of the communications pass from the Mars Odyssey orbiter is too late in the day for team members to gather vital location and health information about the rover after it executed recent commands, so they must wait until the next sol to find out where and how the rover is.)

On Sol 711 (January 2), Spirit roved for 56 meters (184 feet) toward Home Plate, using both blind driving and autonomous navigation. The autonomous-navigation portion of the drive, however, terminated early because the rover could not find a safe path, so she did what she was supposed to do and stopped the drive. Spirit did not resume driving until Sol 713 (January 4), but on that sol she managed to log 80 meters (263 feet) even though she received stall warnings on the left front steer motor on hard left turns, and on the following sol she roved another 62 meters (203 feet). The rover handlers performed a steering test of the left front steering actuator because of the prior stall warnings, but preliminary results showed no more stall warnings. Spirit, meanwhile, had put 198 meters (650 feet) behind her during the first week of the month.

By Sol 717 (January 8), Spirit had roved another 55.4 meters (about 181 feet) closer to Home Plate using a combination of commanded and autonomous navigation, but quickly found herself on slippery terrain, experiencing slippage of 80 percent as the wheels were turning. After a day of untargeted remote sensing, the rover journeyed on, driving 9.3 meters (30.5 feet) on Sol 719 (January 10), but then stopped because the slip rate of her wheels once again exceeded 80 percent in the sandy, unfamiliar terrain. As the rover team viewed the new images and data the rover sent home, Spirit conducted more untargeted remote sensing and atmospheric studies.

“Our intention after leaving El Dorado was to sprint to Home Plate and not stop for anything unless something really wonderful turned up -- and then something really wonderful turned up,” said Squyres. “We were driving along minding our own business when we hit a patch where the rover was slipping and sliding a little bit, and then slipping a lot. In the process of doing all that slipping, the rover churned up some soil. It wasn’t enough churning to make us seriously worry about getting stuck, but it was enough for the rover to decide -- ‘Hey I’m slipping too much. I better just stop and let the guys on the ground figure it out.’ And when we looked at the pictures, we saw that the soil we turned up was very bright, almost white in appearance, very similar to what happened at Paso Robles, a target just below Larry’s Lookout,” he said.

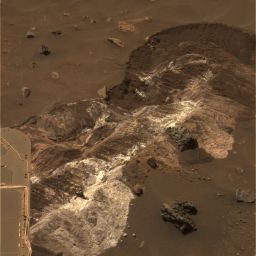

Arad

AradThe white material in this image of the target dubbed Arad, is brighter thanany Spirit has previously seen. It has a powdery and cloddy texture and exhibitsa high abundance of salts, similar in some ways to bright soil deposits seenback at the Paso Robles site that the rover encountered on Sol 431 (March20, 2005) while roving down the northern flank of Husband Hill. Scientists havesince confirmed that these materials have a salty chemistry dominated byiron-bearing sulfates, which may record the past presence of water, as sulfatesare most easily mobilized and concentrated in liquid solution. This view isan approximately true-color composite combining images taken with the PanCam's600-nanometer, 530-nanometer and 480-nanometer filters on Sol 721 (January 12,2006).

Credit: NASA/JPL/Cornell

The team decided this weird white stuff was worth stopping for, so on Sol 721 (January 13), Spirit adjusted her position to place the IDD instruments on the target and settled in for several days of observations, using all her instruments to conduct a campaign of this soil target the team christened Arad. “This was just too good to pass up,” said Squyres. “It had been hundreds of sols and hundreds of meters and we’re at lower elevation than we were at Paso Robles. This clearly had the potential to be something very interesting.”

The data Spirit returned indicate that Arad has a salty chemistry dominated by iron-bearing sulfates, a composition that was indeed similar to that of the more silica-rich target Paso Robles encountered earlier in the rover's journey through the Columbia Hills. The presence of salt of course can be considered another clue to the existence of past water on Mars. “It turns out to be astoundingly rich in ferric sulfate salts, and now holds the record for the highest concentration of salt found on Mars,” informed Squyres. “Interestingly though it does not seem to have the phosphates that Paso Robles did. We’re still working out exactly what it means.”

Once her work was done at Arad, Spirit continued on toward Home Plate, but not without a bit of difficulty driving out of the sandy area near the salty soil target. Rover instruments recorded slip rates as high as 92 percent on the wheels before Spirit's drivers designed a command strategy that took the rover away from the sand dunes on Sol 728 (January 20). “Since leaving Arad, we have just been driving basically as fast as we can given the ruggedness of the terrain,” said Squyres.

As Earth approached the Chinese New Year (The Year of the Dog), which rang in Sunday January 29, the MER team members working with Spirit decided to pay homage to the home country of several members of the MER team and assign Chinese names of gods, warriors, inventors, and scientists, as well as rivers, lakes, and mountains, to the latest series of the rock targets Spirit came across.

“In fact, this has been followed very closely and avidly by the news media in China,” Squyres noted. “Alian Wang [a member of the MER science team from the University of Washington, St Louis] has become something of a media star in China by being interviewed every evening US time / morning Chinese time on national television there. She’s been reporting on the daily activities of Spirit and what rocks we have named and showing pictures of the rocks with the Chinese names, and [her appearances] have become very popular there.”

During the last week or so, Spirit has been maneuvering along the edge of an arc-shaped feature called Lorre Ridge and has passed by some classic examples of basaltic rocks with striking textures. This rover first encountered basalts at her landing site two years ago on a vast plain covered with solidified lava that appeared to have flowed across Gusev Crater. Later, as Spirit climbed Husband Hill, basaltic rocks became rare.

The basaltic rocks that Spirit is now seeing are intriguing because they exhibit many small holes or vesicles or voids, similar to some kinds of volcanic rocks on Earth. Vesicular rocks form when gas bubbles are trapped in lava flows and the rock solidifies around the bubbles. When the gas escapes, it leaves holes in the rock. The quantity of gas bubbles in rocks on Husband Hill varies considerably; some rocks have none and a few have some, and some, such as the rock FuYi, are downright "frothy," as Squyres described them. [In ancient Chinese myth, FuYi was the first great emperor and lived in the east. He explained the theory of "Yin" and "Yang" to his people, invented the net to catch fish, was the first to use fire to cook food, and invented a musical instrument known as the "Se" to accompany his peoples' songs and dances.]

“We’ve been resisting the temptation to actually stop at one those rocks, because we really want to get to Home Plate, but we got lucky a few days ago and had one pop up just by chance in front of us,” Squyres said of the rock they dubbed GongGong. As Spirit’s luck would have it, GongGong was quite a specimen, featuring lots of voids and wind erosion. [GongGong was the king of water from the north who knocked down Mount BuZhou with his head.] “We whipped out the IDD and took what have to be some of the coolest MI images of the whole mission.”

The change in textures and the location of the basalts may be signs that Spirit is driving along the edge of a lava flow, which may or may not be the same as the basalt blanketing the plains near her landing site. The large size and "frothy" nature of the boulders around Lorre Ridge might indicate that eruptions once took place at the edge of the lava flow, where the lava interacted with the rocks of the basin floor. Scientists hope to learn more as Spirit continues to investigate these rocks.

On Sol 733 (last Wednesday) Spirit experienced a dynamic brake error in the left front and right rear steering actuators and engineers halted the drive. On the surface, this appeared to be similar to dynamic brake anomalies experienced on Sols 265 (October 1, 2004) and 277 (October 13, 2004), which involved the right front and left rear steering motors. Analysis and testing at the time indicated that the problem was consistent with a delayed contact on the status relay. The rover engineering team sent a command to ignore the relay status, and the rover completed an autonomous drive of approximately 40 meters (131 feet). In the meantime, however, the team determined that it was safe for the rover to continue driving, but without using the left front and right rear steering motors.

Spirit is currently near the north end of Mitcheltree Ridge, the most significant topographic feature between the rover and Home Plate. It was named in honor of the late Bob Mitcheltree, “one of the real intellectual leaders of Entry, Descent, and Landing team that got our rovers safely down to the surface of Mars,” as Squyres affectionately identified him. “We should get our first close-up look at Home Plate soon.”

From there, the plan is all about McCool Hill. “So, after we get done with Home Plate we’ll be heading out of this Inner Basin and toward McCool Hill on the other side,” explained Joy Crisp, MER project scientist at JPL. “Winter basically means that we will have less energy for science. Beyond the fact that there is less sunlight to power the rovers, Spirit and Opportunity require more energy to stay warm at night. Winter is less of threat for Opportunity, but for Spirit, which is at 15 degrees south, it’s more of an urgent thing to get on north-facing slopes. There’s a fairly large area we can roam around on and it looks interesting,” she added. “We can see brighter patches of rock on the edge of that hill, so there will be lots of things for us to study on those north-facing slopes.”

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

As 2005 gave way to 2006, Opportunity was working away at Olympia, using her Mössbauer spectrometer for a long integration on a target there dubbed Hunt. On Sol 691 (January 2), the rover took her RAT and for 11 minutes brushed Ted, another nearby rock she had been checking out, then reexamined it with the MI and spectrometers. During the rest of the week, the rover continued the Mössbauer spectrometer integration on Ted, took some more images for the Erebus panorama.

Erebus Crater

Erebus CraterOpportunity acquired the images for this panorama of the Erebus Crater on Sols 652 to 663 (November 23 to December 5, 2005 ) while exploring sand dunes and outcrop rocks in Meridiani Planum. Since the time this panorama was acquired, and while engineers have been tending to Opportunity's broken "arm," the panorama has been expanded to include more than 1,300 images of this terrain through all of the PanCam multispectral filters, making it the largest panorama acquired by either rover during the mission, and one that provides the team's highest resolution view yet of the finely-layered outcrop rocks, wind ripples, and small cobbles and grains along the rim of the wide but shallow Erebus Crater. The panorama shown here is an approximate true-color rendering and is presented here as a cylindrical projection. Image-to-image seams have been eliminated from the sky portion of the mosaic to better simulate the vista a person standing on Mars would see.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell

As January wore on, Opportunity did some camera calibrations, mini-TES readings, and also took some sunset pictures, as well as some high-resolution images of the rocks featuring festooned cross-bedding, making the most of her extended visit at the Olympia site. The rover also conducted a calibration of her IDD by putting it into various positions and photographing it with her front hazard-avoidance camera, a calibration activity that the team dubbed Martian T’ai Chi. During this activity, the arm is commanded to a few different positions and the front hazard-avoidance camera takes images at each position. The arm location as reported by the spacecraft is then compared to the location shown in the images so the arm model and camera model can be calibrated against each other.

Normally the team would have stowed the robotic arm since the rover’s IDD work at this location was done, but because the engineers had not yet determined the best stow position, they simply had Opportunity return her arm to the ready position. “We had full confidence that the rover could go on, but we also recognized that this is an inevitable sign of aging,” Crisp told The Planetary Society. “It is a sobering indicator that they won’t keep going and going forever. And that is an additional reason the team wants to try and get to Victoria Crater sooner rather than later.”

On Sol 699 (January 10), Opportunity made some photometry observations with the navigation camera, and began acquiring a high-resolution, blue stereo panorama of the surrounding outcrop, which has been dubbed the Fenway panorama. In the ensuing days, the rover also used her mini-TES to observe the atmosphere and several outcrop targets, and continued her photometry observations. By Sol 701 (January 12), she had completed the Fenway panorama and the photometric observations, and move on to use her PanCam to make thirteen-filter images of a festoon-rich rock called Overgaard.

Opportunity attempted to stow her arm on Sol 704 (January 15), but was not successful, because the shoulder-joint motor stalled once again. Undaunted, the rover moved on to the next task -- using her mini-TES to make some atmospheric observations coordinated with an overflight by the European Space Agency’s Mars Express. Later in the month, the rover successfully conducted more coordinated observations with Mars Express using her PanCam, and also took images of a transit across the Sun by Mars’ moons, Phobos and Deimos.

By mid-January Opportunity had done just about every a rover could do at Olympia. “We did everything we could practically, including some low light angle imaging,” Crisp confirmed. “The rocks we were standing on were just stunning, and we saw more of the festoons, the signs of flowing water, which were clearly represented in the layered bedrock of Olympia, so we took lots of images of those, including many high-resolution images. We also took a lot of images at low Sun angles with the MI and were able to see this incredible texture there – it just brought out the laminations in the rock much nicer.”

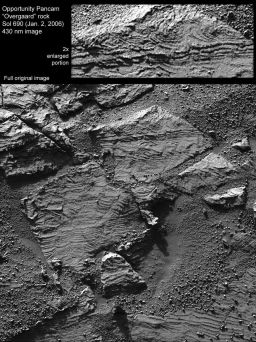

Festoon Patterns in Meridiani Outcrop

Festoon Patterns in Meridiani OutcropOpportunity took this image of a rock called Overgaard with the PanCam at the edge of Erebus Crater on Sol 690 (January 2, 2006). It shows the best examples yet seen in Meridiani Planum outcrop rocks of well-preserved, fine-scale layering and what geologists call "cross-lamination." The uppermost part of the rock, just above the center of the image and in the enlargement at top, shows distinctive centimeter-sized, smile-shaped features that sedimentary geologists call "festoons." The detailed geometric patterns of such nested sets of concave-upward layers in sedimentary rocks imply the presence of small, sinuous sand ripples that form only in water on Earth. Similar festoon cross-lamination and other distinctive sedimentary layer patterns are also visible in other rocks near the rim of Erebus. Essentially, these features are the preserved remnants of tiny (centimeter-sized) underwater sand dunes formed long ago by waves in shallow water Mars' surface.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

On Sol 707 (January 19), Opportunity resumed driving, roving 2.4 meters (7.9 feet) to approach Overgaard, which was chosen for close examination because of its remarkable cross-lamination texture. “We have figured out what the IDD issue was and have worked around it, so that problem has been solved for the time being and Opportunity is back to doing good science again with the IDD,” Squyres said. “We’ve found a way to drive short distances with the IDD deployed, and we used it successfully to get to the lower part of Overgaard,” he added.

Overgaard is a rock that features many interesting sedimentary structures, including “the best current ripples we’ve seen on the whole mission,” Squyres said. “We are shooting some fairly substantial MI mosaics on Overgaard, which is a big enough rock that we actually have to do these mosaics from two different positions. We’re covering enough ground with the MI on this one that we have to do part of the rock and then move the whole rover and do another piece. The MI imaging there has gone beautifully, and we’ve made a move to the upper part of Overgaard, where the festoons are. It might be the most extensive MI coverage we’ve ever done.”

Once Opportunity has imaged all the festoons on Upper Overgaard, the team plans to have the rover check out a couple of other alluring nearby targets at Olympia, including rocks named Bellemont and Roosevelt. “And once that’s done, we’re going to hit the road to the south again to go to the Mogollon Rim,” Squyres said. “We’re not exactly sure how we’re going to attack that site yet, but overall we’re less interested in spending time at the Mogollon Rim than we were previously. The reason being that we’ve done so well at Olympia – all the things we were hoping we’d find at Mogollon we have found already at Olympia. These current ripples are better than anything we have found at Eagle or Endurance or anywhere else, so we feel we’re already reaped our benefit of our visit to Eerebus. There might be something wonderful at Payson [a primary target at the Mogollon Rim] and we’ll see when we get there. A balance is necessary, but our hoped-for drive strategy is a pretty aggressive one, and the team is very anxious to head southward at a brisk pace now to get to Victoria Crater.”

In other MER News . . .

Even as Spirit and Opportunity continued their explorations at their respective regions on Mars, they were starring in a short documentary down here on Earth, as Roving Mars hit the really big screens in IMAX theaters in two dozen cities across the country Friday, January 27. The 40-minute film tells the story of the journey of the rovers as well as the journey of the MER team. Directed by George Butler and produced by Frank Marshall, the movie chronicles the rovers' early development to their treks across Gusev Crater and Meridiani Planum.

Equipping the rovers with IMAX-quality cameras was a priority for the MER mission from the beginning. "We set for ourselves the goal of making two robot field geologists," said Squyres. Jim Bell, leader of the PanCam team for the mission, noted that meant giving the rover cameras 20/20 stereo vision, making MER "the first time we've had human resolution on Mars."

Documenting the mission for a film, though, was not originally in NASA's plans. That idea came together in part thanks to Squyres' younger brother, Tim, an Academy Award-nominated film editor. The younger Squyres pitched the idea to Butler and Marshall, who then did their own share of pitching to the space agency before NASA finally granted them access for filming. The pivotal point occurred just before Spirit's launch in June 2003, when tension was at its peak and the team couldn’t afford to be slowed down by a camera crew. So Butler rented the IMAX theater at Cape Canaveral to show the MER team his last movie -- a documentary about the journey of Antarctic explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton. "You could feel this chill go through the room," Squyres remembered. From that moment, Butler's film crews had full access.

Still, neither Butler's crews nor the rovers' cameras on Mars could capture images of the rovers themselves once they were in orbit. So Dan Maas -- creator of Emmy-nominated Maas Digital in Ithaca, New York, and the animated video of the Mars Exploration Rovers arriving, landing, and roving around Mars -- rendered the magic. For Roving Mars, Maas delivered brilliantly, said Squyres -- creating a seamless transition between actual footage and 12 minutes of lifelike animation that is true to the mission data. It's all meticulously "real," he noted, from the placement of rocks on the surface of Mars to the way the rovers bounced down on opposite sides of the planet in January 2004 ensconced in big balloon-like airbags.

The film, which is sponsored by Lockheed Martin and distributed by the Walt Disney Company, is not heavy on the science, but it does make for a rover ride that captures the spirit of exploration and the opportunity before humankind to go where no human has gone before.

“It was a thrill,” Squyres said after seeing the film’s premiere. “Whenever you‘re the subject of a documentary you approach it with a little bit of trepidation when you see it for the first time, but I thought they did a wonderful job with it. This story is a very visual, almost a cinematic story at its heart anyway, so IMAX is actually a very good medium for telling this story. One of the high points for me of course is that they acquired some spectacular footage of the rovers during final assembly and testing at Cape Canaveral, so you see these beautiful IMAX shots of the two rovers in the high bay at the Cape, just glorious looking stuff. There’s a wonderful launch sequence, then the landings animated by Dan Maas -- this is Dan Maas working at IMAX resolution and it is absolutely spectacular.”

As a scientist, Squyres said the best part of the film was seeing the PanCam images on the really big screen. “I’ve know for more than 15 years that once we finally somehow got PanCam to Mars it was going to deliver IMAX quality images,” he said. “Knowing that intellectually and having the equations to prove it is one thing, but to actually see an IMAX image from Mars on a screen in front of you entirely, well . . . it was a very moving thing for me to see our pictures in that format.”

From the audience perspective, if viewers -- especially the youngest ones -- get inspired to do some exploration of their own, Squyres said, the movie will have served its purpose. "What I would most like is if some kid watches this movie and says, 'I want to go there.’ And then actually does it."

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth