Emily Lakdawalla • Dec 06, 2007

More on the Chang'e image flap

So the story that I wrote about the Chang'e image not being fake but also containing a small processing error has been propagating across the Internet -- it showed up in Alan Boyle's Cosmic Log on MSNBC, on John Borland's Wired Science blog, and on New Scientist's blog, among many other places. These other blogs have all treated the story pretty evenhandedly, but I've been dismayed by the color of the commentary in the replies by readers of these blogs; so many people are unwilling to drop the idea that the images were somehow faked, with the obvious subtext being that those Chinese can't be trusted. I agree with John Borland, who commented:

It's odd that moon images are so often questioned. We can do so many other things that stagger the imagination; why are people reluctant to believe that we can't go to the Moon? I find it also particularly interesting that many people are apparently willing to believe something so improbable (faking a moon mission? That's serious business, way harder than faking a memoir or a resume).Skepticism is certainly useful, but there's an ugly scent in the air when so much extraordinarily bitter criticism gets leveled at China in particular.

Some may call me too much of an optimist, but I'll tell you a story. When I was in graduate school at Brown University, I was privileged to have daily interactions with several Russian planetary scientists, including Sasha Basilevsky, Misha Ivanov, and Misha Kreslavsky. This was well after the Soviet Union fell so it wasn't that unusual for Russian and American scientists to be working together. But the working relationships between these scientists and my advisor, Jim Head, had been formed years earlier when the level of distrust between the Soviet Union and the United States was higher than the level of distrust is between the United States and China is now. Somehow, Jim and Sasha and many other participants managed to forge close working relationships including the exchange of data, even convening meetings taking place in Providence and Moscow every year from 1985 on, to facilitate cooperation and exchange among scientists from both sides of the Iron Curtain.

It is possible, even in extremely tense diplomatic circumstances, for science to unite us. I won't deny that there is nationalism behind space missions -- if there weren't any nationalistic goals, governments probably wouldn't pay the bills -- but even if the program itself is intensely nationalistic, the science that happens as a result of the space program is usually much less so. There is so much international exchange among scientists, beginning when graduate students acquire their educations in countries other than their native ones, that space science tends to break down barriers among countries. At its heart, science is a quest for truth and clarity; to be accused of falsifying data is probably the worst thing that can happen to a scientist (professionally speaking), and I don't believe that Chinese scientists are any different from any other scientists in this regard. How distressing it must be for the Chang'e team to be so accused! I am happy to say that the comments I've received directly from you, dear readers, have not shown this kind of prejudice.

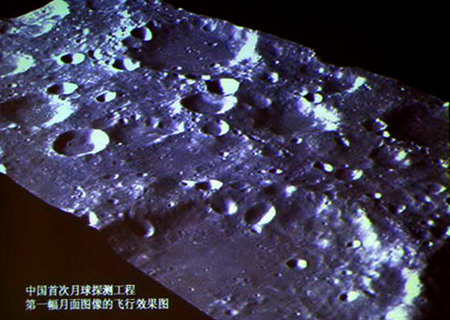

I'll repost again the pretty picture in question:

CAST

Chang'e 1's first picture of the Moon (with scale bar)

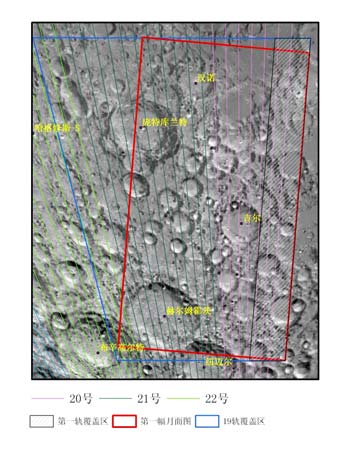

This image is the first returned from the Moon by Chang'e 1, China's first spacecraft beyond Earth orbit. The 19 separate images that compose this view were captured over two days, November 20 and 21. Each image was 60 kilometers wide; the entire image is about 460 kilometers long and 280 kilometers wide, located within a box from 54 to 70 degrees south latitude and 57 to 83 degrees east longitude. It includes mostly areas of highlands but contains some of the dark basalt plains of Mare Australe at the upper right. The scale bar at lower right is 50 kilometers long. The 66-kilometer-diameter crater Gill is just to the lower right of center in this image. Cut off at the upper left side is 91-kilometer Pontecoulant. At the bottom edge is 94-kilometer Helmholtz.

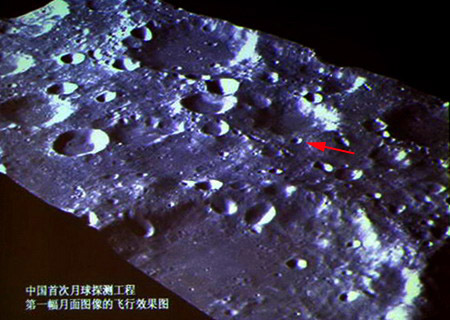

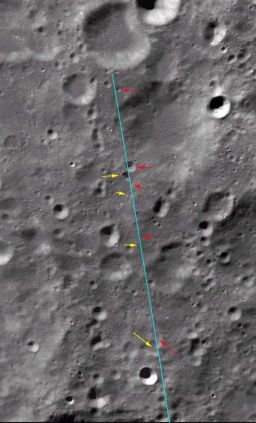

CAST / "Mei de Yan Jing"

Seam in the Chang'e mosaic

An individual posting on a Chinese language space discussion forum located several features in the first image from Chang'e 1 that are offset across an image seam. He found that there appeared to be a displacement of about 3 kilometers along a few-hundred-kilometer stretch of the image seam, and that it seems to be no more than an inadvertent mistake.

CAST

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth