A.J.S. Rayl • Apr 26, 2019

The Mars Exploration Rovers Update: The Final Report

Sols 5354 - 5399

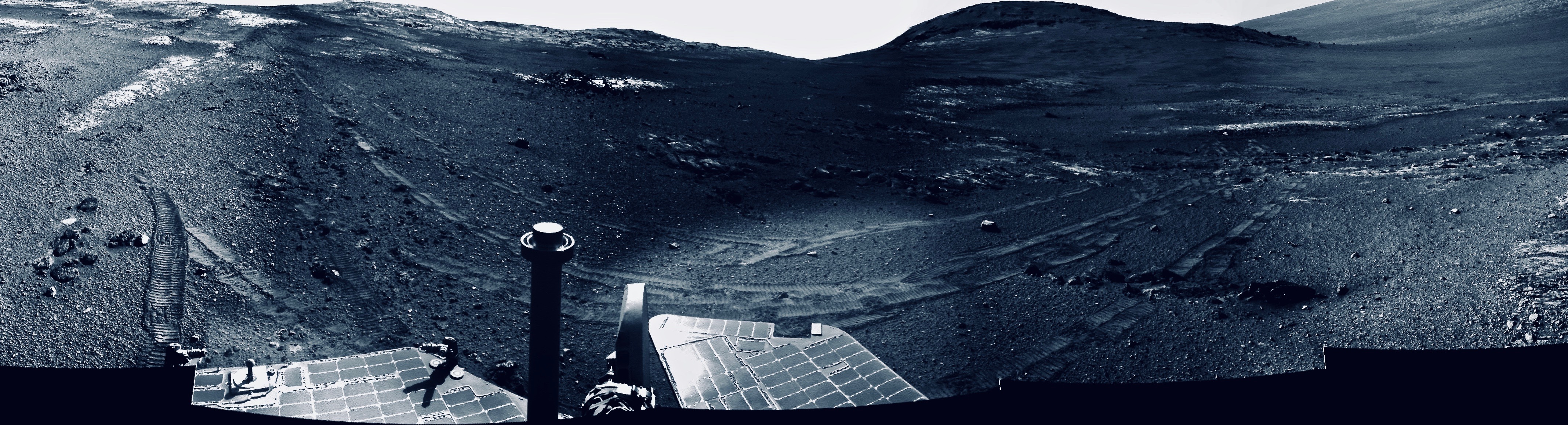

It’s a fall afternoon at Endeavour Crater as I type this final report of The Mars Exploration Rovers Update. The salmon colored sky is clear and cool. It’s the sort of sol Opportunity would revel in I imagine, as close to a perfect Martian day as they get.

The summer winds finally lost their energy and the dust storm season is over. But there are no more signals coming from Earth. No more comm sessions with the orbiters. Nothing like it used to be.

Opportunity is parked right there. Exactly where she was when that monster dust storm blotted out the Sun and forced her to shut down last June. Just about halfway down this valley they named Perseverance – for what it took them to get here.

It’s kind of weird, but winds on Mars don’t blow with the forces of winds on Earth and so Opportunity was able to hold her ground during the storm even as it turned into a huge dust cloud that wrapped around the entire planet. She was at ground zero for days during that storm, the worst we’ve ever seen, and she didn’t move a bit. Not a bit. Doesn’t look like it anyway.

The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter passed over Endeavour Crater some weeks ago and HiRISE took another picture. With its telescopic lens, this camera produces high-resolution images in which you can actually see objects on the surface as small as one meter. What you can’t see is how dusty that object is or isn’t. But the scientists, with their advanced imaging research tools and knowledge, report no obvious changes in the surrounding environment.

Some people, maybe more than you would think, held on to last-rites hopes that Opportunity might surprise everybody one more time and light the Deep Space Network boards before the fall equinox March 23rd. She didn’t.

The rover that loved to rove isn’t roving anywhere anymore, not in our lifetime anyway. Opportunity is a monument to exploration now, like Spirit has been since 2011. These two priceless artifacts of the first overland expeditions of Mars are resting in peace, right where Mars brought an end to their missions.

Considering all that happened to get them here, from California to Florida, from Earth to Mars, to Gusev Crater, to the plains of Meridiani – well, that is righteously poetic.

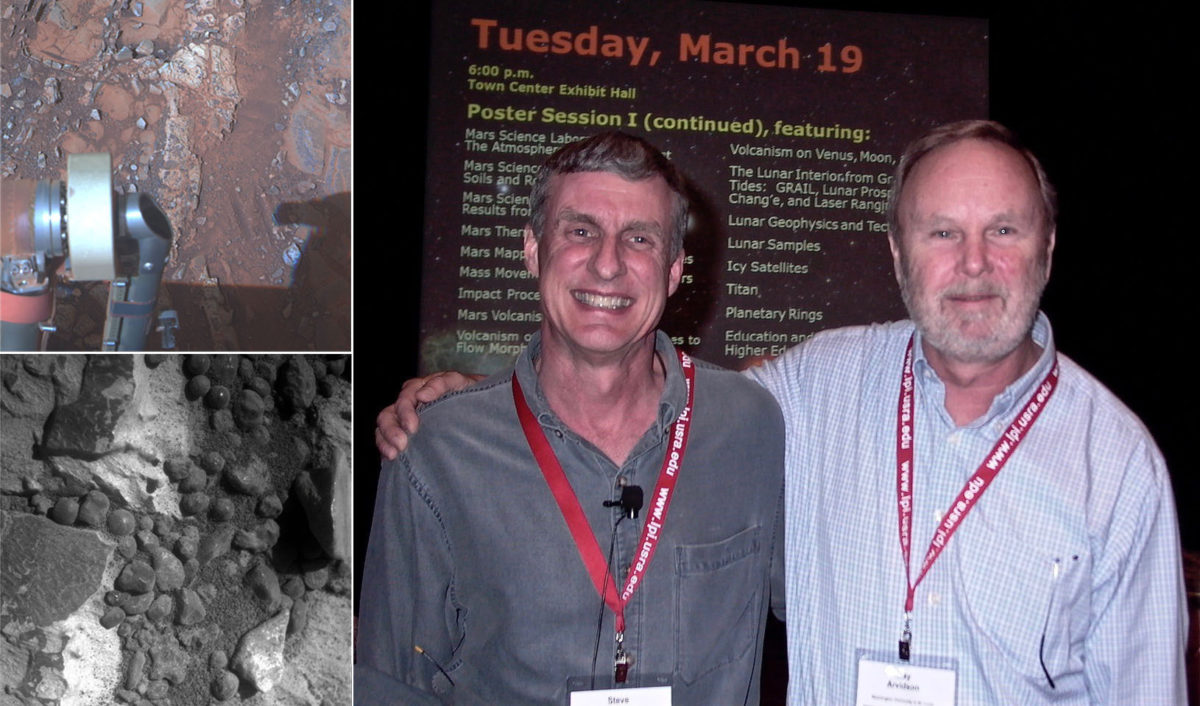

“I didn’t know how I was going to feel when the mission ended – if I was going to feel a deep sense of loss and mourning or if I was not going to care or if I was going to feel triumphant,” reflected MER’s Principal Investigator Steve Squyres during a recent conversation. “The reality is, I’ve been pleasantly surprised about how good I feel. We did what we set out to do and much more, the mission ended as well as something like this could possibly end, and we can walk away with our heads held very high.”

In point of many facts, MER is a triumph in planetary exploration that stands alone. This mission team literally set the bar, rather launched the bar for exploring the surface of Mars, logging an impressively long list of ‘firsts,’ the most significant of which is establishing the first sustained human presence on the surface of the Red Planet.

None of it came easy. Mars is hard and from the very beginning to the very end, the MER team roved against the odds, often against all odds.

“I’ve had a lot of people who’ve come up to me over the years and say: ‘It’s a miracle Opportunity lasted so long,’ and I just wanted to say, ‘It’s a miracle Opportunity got to Florida!’” said Squyres, the James A. Weeks Professor of Physical Sciences at Cornell. “It really was miraculous. From the day NASA finally said: ‘Go – and by the way, can you build two,’ we had 34 months. It was crazy.”

Yet they managed to pull it off. Spirit and Opportunity made it to Cape Canaveral and one after the other launched into blue-sky afternoons in the summer of 2003. But the reality in those days was that 2 in 3 missions to Mars failed and given all the technical difficulties the mission experienced just to get to the Cape, most people outside the team didn’t think getting these two rovers down on the Martian surface safely was even possible.

Seven months later however, the MER team beat the odds. Both rovers bounced down on Mars in landings that were nothing short of jaw-dropping spectacular, and so near flawless the Entry Descent and Landing (EDL) team made it look easy.

Once the twin robot field geologists were up and roving, the operations teams kept making it happen, handling every twist, every turn, usually to command their rovers on to set a new record or uncover the next science discovery. And the findings and the records turned out to be more than they ever thought they could achieve.

Opportunity collected data for the first time that allowed scientists to examine sedimentary rock record of another planet, and to infer that in the distant past there were shallow lakes on Mars. It was huge, and a dream of a discovery for the MER scientists. The age-old belief that Mars was once warm and wet and more like Earth with potentially habitable environments was at long last backed with scientific evidence from the surface.

From there, this rover went on to become the first to venture into a crater, the first to explore the rim of a huge crater billions of years old, and the first to complete a marathon on a planet beyond Earth, chalking up science findings as she roved.

On the other side of the planet, Spirit became the first rover on Mars to photograph a dust devil and the first to climb a hill the height of the Statue of Liberty. Then she took a geologic tour of the Inner Basin of the Columbia Hills even after her right front wheel stopping working, defining MER mettle with almost every rove. Driving backwards and dragging her wheel, she serendipitously churned up near pure silica, one of the mission’s biggest discoveries.

The data Spirit collected in this area around a formation named Home Plate gave the scientists the evidence they needed to uncover an ancient environment where volcanoes spewed ash, water and steam came up from underground, and hot springs bubbled. The silica sinters she found there may entomb microbes and other tiny organisms, like they do on Earth. That’s life. Very small life. But big enough to make Gusev worth visiting again.

Over and over this team beat the odds and achieved so many seemingly impossible feats that I began calling it "the miracle mission to Mars."

MER was social before social media. It was the first mission to open the door and give anyone with a computer and Internet access a “ticket” to follow the excursions in Gusev Crater and in Meridiani Planum, to see the raw data coming from the rovers at the same time the team did. That open door brought people from all kinds of places around the world together, widened everyone’s horizons, and offered a new perspective on Mars and on our world that would grow as the mission rolled.

Those who picked up that ticket to ride, they knew. MER surely did become the best reality show ever, with textbook changing science findings, engineering advances and rover records, all those captivating images, and “lessons learned” adventures to show for it, more than 7.5 terabytes worth.

But a miracle mission? Here’s the thing: There were two highly complex rovers. There were human colleagues. There was Mars. And there was NASA Headquarters. All those elements had to be functioning and pretty seamlessly interacting for all the trials and tribulations to be won and for the mission to keep moving ever onward, day after day, sol after sol, year after year.

What’s truly noteworthy is that a band of disparate scientists, engineers, and two robot field geologists that often exhibited minds of their own pulled all this off for 15 years on the surface of Mars, for an estimated total cost of $1.1 billion: $820 million for start up and the primary mission, the rest for nearly a decade and a half of operations – with a return on the government’s investment that is already incalculable.

It’s getting close to sunset here at Endeavour. Seeing Oppy in this light is so poignant...and inspiriting at the same time. One thing I know for sure right now is this: in their dust, the MER team and these two fearless rovers are leaving behind a legacy that will live on for decades.

But before NASA turns out the last lights on this remarkable, legendary mission, there’s one more objective to be met on Earth.

It’s been about two months since NASA’s Associate Administrator for Science Thomas Zurbuchen declared that Opportunity’s near 15-year-long expedition – and the Mars Exploration Rovers (MER) mission – were “complete.” With that declaration, made during a televised event at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) the birthplace of and mission control for all NASA’s spacecraft at Mars, MER officially roved into the final phase of its existence.

It’s called the “closeout,” and it’s something every NASA project goes through at the end of its mission. During this phase, scheduled to last for six months after shutdown, the MER leadership and a small group of the team’s scientists and engineers continue to report for MER duty in some capacity to complete the preservation of the mission’s legacy in NASA’s Planetary Data System (PDS).

Managed by NASA Headquarters, the PDS is the U.S. Government’s long-term electronic vault where well documented, peer reviewed data from its planetary missions are stored. It is an active archive that makes this data available to the research community and the public. It’s immense, and it’s operated and maintained in a number of institutions across the country.

Orchestrating the transfer of data from MER to the PDS is Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson, who is the mission’s Chair of the Data and Archive Working Group. He also happens to be Manager of the PDS Geosciences Node, the lead node for Mars missions, which is based at Washington University St. Louis (WUSTL), where Arvidson is the James S. McDonnell Distinguished Professor of Earth & Planetary Sciences.

There in St. Louis, Arvidson and 10 PDS staff members have the responsibility of maintaining this node of the PDS. That means they are the ones who upload and archive data, and make available some 300 terabytes of data from all NASA’s missions to the inner planets and the Moon. Right now, MER is top priority.

“We’re spending a lot of time to make sure that we capture as much information as possible, everything that Spirit and Opportunity and the team did before the project closes its door,” said Arvidson.

“The closeout is important,” Squyres noted. “How people choose to view this mission’s legacy months, years, and decades from now, I can’t predict, can’t guide it, wouldn’t want to try. But what we can do is provide the raw material, the data and images, and the lessons we’ve learned, so that there’s a permanent record for researchers and students and other scientists and engineers.”

Under Arvidson’s watch, the PDS Geosciences Node staff is working in full tilt mode establishing that permanent record. As part of the process, they are also reformatting all data files to the latest PDS format and structure. It’s quite an operation and they expect the pace to continue for at least the next four months. That’s what it will take to get all the MER planetary science and engineering data properly organized and archived.

When it comes to the more than 340,000 raw images that Spirit and Opportunity took with their Panoramic Cameras (Pancams), Navigation Cameras (Navcams), and Hazard Cameras (Hazcams), the PDS Imaging Science and Cartography Node at the United States Geological Survey (USGS) in Flagstaff, Arizona shares responsibility with the Geosciences Node for ensuring those are archived.

“All raw engineering camera images will be archived in the PDS and even most of the processed images (Navcam mosaics, stereo range maps, etcetera) will be archived,” said Planetary Society President Jim Bell, lead scientist on the Pancams, of Arizona State University (ASU). The 220,534 raw Pancam images are already archived in the PDS. “We've been posting, on Pancam Home, and archiving all of the Pancam mosaics too,” he added. “We'll finish that work over the next three to six months.”

MER produced a mountain of raw material in its 14-and-a-half years of surface exploration and research. While all raw data and most of the data from the rover’s science instruments have been archived in the PDS, the team is currently renewing an emphasis on remaining derived data, including documentation and engineering data not yet archived.

“There’s a lot going on,” said Arvidson, who recently reached out to MER scientists across the country seeking papers or anything else they deem absolutely, positively essential for saving for history’s sake. These conversations jogged memories and stirred recollections and realizations, as well as initiated actions to ensure that the archiving of all important remaining data and documentation gets done. “This is how we make sure we’re leaving the doors to new discoveries open,” he said.

Since MER was a science driven mission and the rovers were almost always moving, a lot of team members have data waiting on back-shelves. “We were always going somewhere and there wasn’t a lot of time to sit back and dig deeply into the data,” Arvidson explained. “Our goal now is to gather and organize all the rest of the data, get it all in the archive, and do that in an orderly fashion before the funding goes away.”

Funding is always a challenge in this business of space. There is money in MER’s coffers reserved for the closeout. But at the risk of being redundant, this mission went on continuously for nearly 15 years, a lot of stuff had to be put on hold because the action never stopped, and there are things that were not previously contemplated for preservation that are now deemed necessary.

Although MER was budgeted through 2019, since Opportunity was officially decommissioned February 13th, its operations funds were reprogrammed to Mars 2020. Therefore, the resources for MER archiving are what they are, and the mission’s Project Manager John Callas is working to button everything up by mid-August, before the end of NASA’s fiscal year in September. “We’re trying to do things as best we can under the conditions we have,” Callas said.

No one’s stopping to worry about funding right now and nothing, it would appear, is going to stop this mission team from saving its history. Just like when they were on the Martian road, the MER closeout group is going above and beyond and working hard to do this right.

Arvidson and the team in St. Louis are working with Callas and MER Rover Driver Heather Justice, for example, to gather all the rover mobility data and engineering telemetry so they can ‘park’ it in a new section within the PDS MER Archive. No one ever thought about creating an archive for rover mobility at the beginning of the mission, because, frankly, few expected Spirit or Opportunity to survive much past their 90-day primary missions, if that long.

“The plan now is to include the engineering telemetry acquired during drives in order to generate a new archive that can be of use for understanding rover mobility and terramechanics, how the rovers’ wheels interact with the Martian terrain and soils,” said Arvidson.

After nearly a decade and a half of driving on Mars, the telemetry or measurements collected while the rovers were moving, is “a treasure of information,” said MER Rover Planner and JPL robotics specialist Paolo Bellutta, who developed software that merged orbital views with ground imagery to help better chart the rovers’ routes. Most of these data have only “rudimentarily” been processed and analyzed, he added.

The rover mobility data contain a considerable amount of information on terramechanics. “Our wheels were in contact with Mars soil for a total of more than 52 kilometers (32.31 miles) and the recorded data must contain some valuable information that can help us map the Martian terrain along the paths the rovers’ took,” said Bellutta. “I can't wait to see what others can do with this data.”

The driving capabilities of Spirit and Opportunity, their patterns, idiosyncrasies, and the terramechanics, on Earth as well as on Mars, is what informed, taught, and guided the Rover Planners, ops team members, and the scientists who cared to know about how their field geologists were faring on the road. That is to note, the rovers did their part in helping to form “the best rover team in the solar system,” as Callas defined the MER ops crews.

The MERchivists are also uploading all documentation from the mission that might be of use for future researchers, like lessons learned, and any other engineering and science data that’s ‘fit to PDS.’ “Our lessons learned are especially important, because these are things that potentially could benefit other missions that NASA is conducting right now, and those it intends to conduct in the future,” said Squyres.

Meanwhile, they’re adding the mission’s logs to the Analyst’s Notebook sections of the MER Archive. These documents and graphics preserve the narratives of team meetings generated during planning and data analysis, the debates and decisions therein, which capture some of the ways and means the team blended science and engineering in their meetings, Callas pointed out.

Then, of course, there is the brimming-over abundance of science data at the core of this mission archive: a total volume to date of 4.97 terabytes (TB) from Oppy; and 2.68 TB from Spirit. “Research from data mining the science from Spirit and Opportunity could easily extend decades into the future,” said Arvidson.

MER science team members have already shown there are new discoveries to be found in these troves of Martian treasures. MER Athena Science Team member Richard V. (Dick) Morris, of NASA’s Johnson Space Center, led a group of team scientists that discovered evidence for the first carbonates on Mars, specifically magnesium-iron carbonate minerals, signs of near-neutral water on Mars, like water we would drink on Earth. It was another huge finding.

Morris, et al., published nearly five years after Spirit collected the evidence from a rock outcrop called Comanche while hiking down Husband Hill. They attribute the presence of these carbonates to hydrothermal activity, caused by volcanic activity in the area. Long story short, as the biology adage goes: where there is water, there is life. Did life once form long, long ago where Spirit roved? It’s possible.

Steve Ruff, a MER Athena Science Team member, of ASU, has called Spirit’s data from the Home Plate area “the gift that keeps on giving.” A member of Morris’ team, Ruff kept digging into the data this rover collected and in 2014 reported that he had uncovered evidence to show low temperature surface waters may have introduced the carbonates into Comanche, rather than hot water rising from deep down. He was suggesting an ancient lake that many planetary scientists thought once filled Gusev may have existed.

Ruff kept researching and after more findings in Spirit’s data, his hypothesis evolved. While he still views the lake hypothesis for Comanche carbonates, which involves alteration of olivine, as a candidate process, he has broadened his theory to include other sources for the fluids. “Any water in contact with the dense CO2 atmosphere in the Noachian Period would turn into carbonic acid,” he said. “So lake water, snow melt, rain, and even near surface ground water could have led to carbonic acid alteration of olivine-rich materials to produce carbonates.”

Time and more research may tell. Sometimes it just takes a little perseverance and determination, something MER team members have taught young researchers by example.

“My hope is there will be a student or researcher in the future who will make major discoveries because we’ve done a good job archiving as much data and documentation and information as we can,” said Arvidson. “As we view it, this work we’re doing now offers a major return on investment.”

At the same time as all the archiving is going on, Callas is preparing The Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity End of Mission Report. With science input from Squyres, Arvidson, and MER Project Scientist Matt Golombek, and rover engineering input from Chief of MER Engineering Bill Nelson, Callas, as MER Project Manager, will pull it all together into the final document and submit it to NASA HQ.

In outlining the report, they came up with a way to contain the effort that could have easily careened in many different directions: do not duplicate. Therefore, the end of mission (EOM) report will not encompass things that have already been written about or published in journals.

“What we’re going to do is capture the period of time, probably from Perseverance Valley to date, and report on that,” Callas said. “That’s the approach. We don’t have the time or resources to do anything more ambitious than that, and really, anything more ambitious would likely be duplicative with the stuff that’s already been released.”

Since Opportunity will never finish the research in Perseverance, the MER scientists can’t say for certain what formed this unique geologic formation in Endeavour’s rim, which was the primary science objective at this site. From orbit, this valley looks like a river system, but on the ground, evidence the rover found before being stopped by the storm seems to be pointing to something else.

Most of the working hypotheses officially remain on the table. Therefore, it is likely that the EOM report will discuss these hypotheses and how Opportunity’s data offer varying degrees of support, or not, for each, narrowing them down a bit in the process.

MER science team member Rob Sullivan, a Senior Research Associate in the Center for Astrophysics and Planetary Science at Cornell, offered a preview at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC) held in Texas in late March. In brief: problems with hypotheses involving flowing surface water remain difficult to solve, because many of Opportunity’s observations are consistent with a long history of fracturing and faulting combined with wind erosion, rather than water flowing downslope.

The lingering mystery of Perseverance aside, the MER Archive in the Planetary Data System promises to be as comprehensive as mission archives get, complete with a bounty of bonus prizes in the form of chance finds just waiting for prepared minds.

When all is archived and done, MER just may be the best-documented planetary exploration mission to date, and The Mars Exploration Rovers Update might have a little something to do with that. As the rovers trundled across the Martian terrain, as the scientists chose destinations, collected data, made discoveries, wrote papers, and re-wrote textbooks, and as the engineers developed software upgrades to increase the rovers’ intelligence, honed methods of negotiating the Martian terrain, and innovated ways to determine the rovers’ routes, I collected data on them and from them, documenting the mission journalistically in-detail.

Emerging from the dozens of news stores and features I wrote during the mission’s first couple of years, this highly formatted monthly news feature is now a mission-long series archived here. It gets better. The Mars Exploration Rovers Update Archive has recently been bolstered with and is part of a new MER Mission Page that is replete with fast-facts, quick-look summaries with links, and collections of images. Suffice it to note: the MER mission is well preserved on The Planetary Society’s website.

Spirit and Opportunity live!

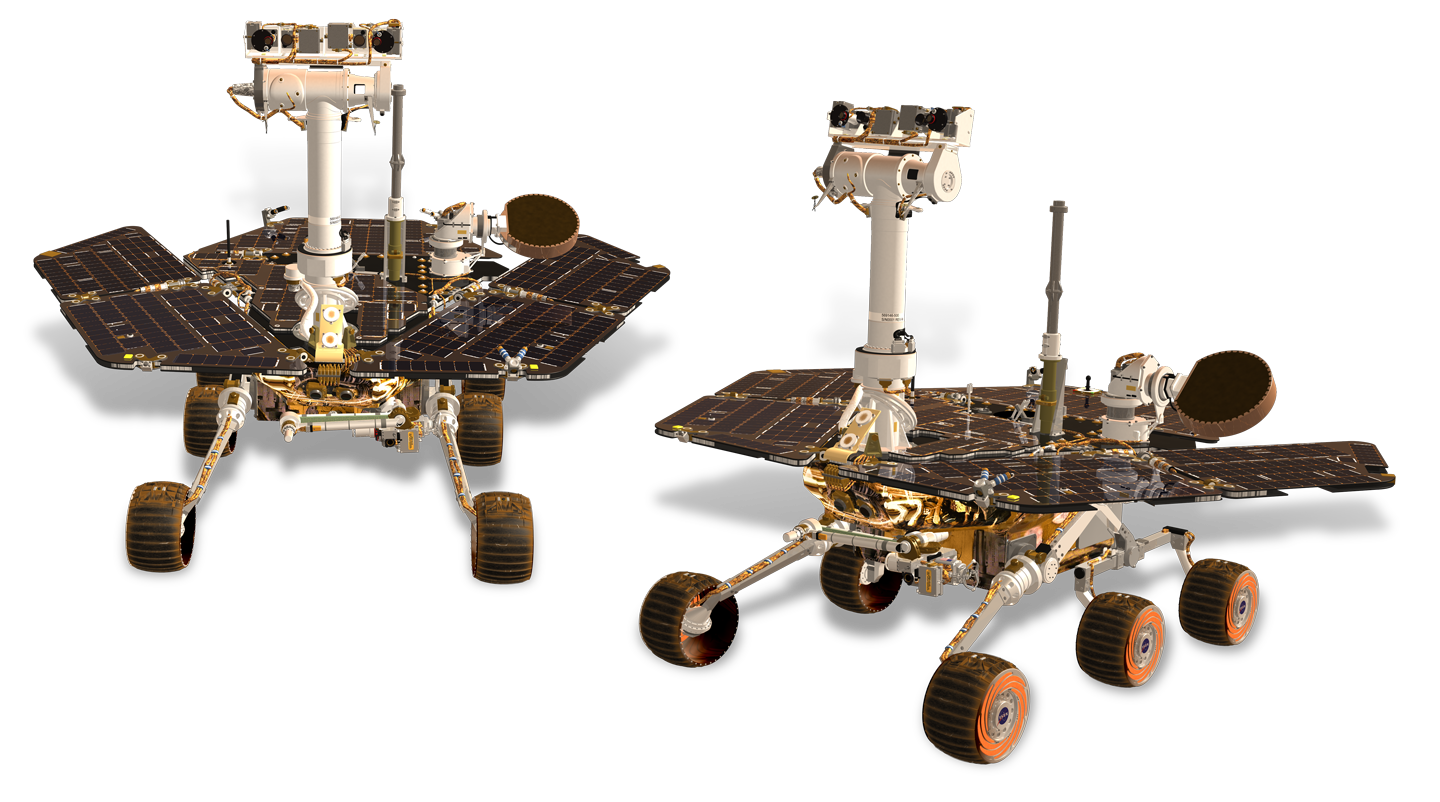

Another part of the MER legacy has been cruising along in our global culture, our art, and our science for years now. The rovers’ image has become iconic; their symmetry – head, two eyes, neck, body, two winglets, one arm and six wheels – is imprinted in human minds around the world and has inspired all kinds of things.

Consider WALL-E, who became a huge star in his own cartoon right — or the knock-off rovers in big brand commercials — or the real Chinese solar-powered rover that recently tooled around the Moon. MER merged smoothly into the lanes of pop culture and science.

Actually, the inspirational impact of these two little bots cannot be quantified and it cannot be underestimated. Spirit and Opportunity were, metaphorically speaking, like beacons flashing ‘yes’ from Mars, and almost overnight they became cultural touchstones for Millennials and Post-Millennials, much like Apollo XI was for Baby Boomers in the 1960s.

The twin, golf-cart-size robot heroes engaged students and kids, turned them on to science, technology, and math, and some now have careers in planetary science. In its last configuration, the MER ops teams featured more than a dozen engineers and scientists who were in middle school or high school when Spirit and Opportunity landed, and many of them are young women.

But no matter the gender or generation, all the younger professionals who found their way to this mission had a dream...to drive a rover on Mars...to understand what cross-bedding is...to model the Martian atmosphere...to have Opportunity take “a proper self portrait” and more.

Spirit and Opportunity eased us all into the 21st Century and a new era and style of planetary exploration. The notion of rovers on Mars, so Jetsons for Boomers, became a been-there-done-that kind of normal, and with a little precursory help from science fiction and, in particular Star Wars’ R2D2 and C3PO, the MERs helped Earthlings warm-up to the future, and accept robots as genuine colleagues.

MER also lives on in the breathtaking, full color Martian panoramas that grace our computer screens and hallways and that transport us to a planet that has forever fascinated our species. Huge, almost haunting photographs from a place once so mysterious are real, courtesy Spirit and Opportunity, and they have made Mars a more familiar neighbor.

From the summits of Husband Hill to the Inner Basin in Gusev, from the drive out of Eagle Crater and onto the plains of Meridiani and into Endurance Crater, then Victoria Crater and Endeavour and Perseverance Valley, we know these places now. We have seen there. How could these stunning photographic landscapes have not helped stir the burst of wanderlust for Mars and further embolden the crusades to send a human crew there, despite the deadly and still far from resolved problem of radiation.

Truth told, MER also gave untold numbers among us a place to escape, a place to seek solace when the insanity, greed, and brutality among various tribes of people on Earth got to be too much. Going to Mars offered a respite, even served to restore hope in humanity, for the best of humanity seemed infused in these two little robots exploring Mars with the wide-eyed innocence and enthusiasm of strangers in a strange land.

The MER image and likeness, the jumbo “picture postcards,” the inspiration the mission has given to people of all ages, are part of the mission’s cultural legacy that is in the wild now going where it will. But that’s not all.

Another part of the MER legacy is roving on in the wild now too, and there’s no telling what it may produce or how far its reach will be.

Making great things happen

Spirit and Opportunity redefined the words ‘enduring’ and ‘resilient’ and each is a testament to American engineering, of that there is no doubt. But the keys to the MER mission’s success have just as often been in the hands of the rovers’ colleagues on Earth who put their human brains, hearts, passions, hopes, dreams, and time into creating and then keeping these marvels of machines blazing new trails.

Almost every day on Mars was a master class in teamwork. It started in the beginning with the mission’s leadership: the original MER Project Manager JPL’s Pete Theisinger and Squyres. They set the tone with one big objective, a plan on how to achieve it, and directives to steer the mission team forth united.

“It’s not just about landing. We’ve done that,” Theisinger told his engineers, referring to the first, trial rover mission, Pathfinder/Sojourner in 1997. “This mission is about the science.”

Squyres advanced that directive with a motto for the scientists – “Every day on Mars is a gift” – and with his contagious, engaging optimism he etched that motto into the mission mindset. He also handed out a set of formal, written “Rules of the Martian Road.” In addition to specific guidelines, everyone learned the overarching strategy right away: the mission would be driven by the science and exploration, not by what each science instrument could do at a given stop.

Underpinning the MER road philosophy were tried and true, time-tested principles and values: commitment, determination, teamwork, respect, courage, integrity, and equality. Everyone, no matter their credentials, no matter their career status or age, no matter whether they were an engineer or scientist or student, every individual was respected and not only invited to speak in team meetings, but were expected to speak out if they had an idea and especially if they saw or sensed something wasn’t right.

Character mattered on MER. Scientists and engineers alike were trusted and allowed the freedom to do their jobs. They assumed their responsibilities and were accountable to each other and the mission, and, importantly, everyone accepted that they were not always going to get to do what they wanted.

The one absolutely critical component was individual will; the willingness of each of the individuals, the thousands of individuals who signed on and made a commitment to the mission and their objective in the matrix. Whether they made the wires or cables, the solar cells, science instruments, or wheels, or fashioned the composite materials or mixed the chemicals for the batteries, or were on the development or operations teams or the science team – everyone did what they committed to doing and more. In today’s world, that, by my experience, is a miracle.

Squyres also had a litmus test for the scientists. Being a scientist, he knew well the effect of a miserable and unhappy scientist. It was a simple question: ‘Are you happy?’ It didn’t happen often, but if the answer was ‘no,’ he set out to resolve the situation; if it involved others, everyone was heard, the goal being to turn the ‘no’ into ‘yes.’

Perhaps the single most important thing Squyres did was create an environment that would bring scientists and engineers together. Beyond joint meetings, he encouraged engineers to take part in or observe science tasks, and assigned scientists to work with engineers on some of the light engineering tasks. The mix blended, cohesive came out, and a mission culture was born.

Accepting to acknowledge, accept, and respect ‘the other,’ served the mission, the rovers, and the humans. Theisinger and Squyres instilled a work ethos in MER and gratitude would play a huge role from Day One to The End.

Going to work on Mars became routine immediately. Each morning, engineers and scientists alike got their morning coffee or tea and opened up the files of images and data downlinked overnight from the rovers. Then, typically they would review the data, mentally teleport themselves to the rover’s site, and prepare for the work ahead.

The MERtians devoted themselves to their jobs and their robots. For seven years, they were working in two places at once, and a rover’s life, the mission’s life depended on them. They were cognizant of that every minute of every day.

The ethos resonated deeply, so deeply that team members lived their lives around the rovers and Mars. They scheduled life events, even the birth of children, around the Martian seasons and sacrificed many of Earth’s holidays. Every day they went to work on Mars and were happy for it. Mars became their new normal, Gusev Crater and/or Meridiani Planum their second homes.

Through the years, the bonds deepened and the entire team eventually would turn into one big family, a family that genuinely seemed to like each other even in the moments when they didn’t. In the space community, MER was admired, envied even. Everyone knew this mission was special. Still, there was something more, something different than any other mission I’d ever covered.

It was the way team members interacted with Spirit and Opportunity. Anyone who has followed the mission and The MER Update knows well that these two robots became way more than buckets of bolts or tools for so many on this team of Mars pioneers, not to mention their many followers around world. These rovers were, after all, Earth’s emissaries doing our bidding.

Designed to be identical twins, Spirit and Opportunity actually exhibited different personalities from the beginning, Callas told me years ago. He spent many nights with them in their “incubation room” during development. Spirit’s “infant” quirks likely resulted because everything was tested first on the alpha twin, so she bore the brunt of breakdowns and things going wrong. Opportunity benefited from that, but their individual “traits” would become clear soon enough.

It was established early on and revealed at a pre-landing press conference that these rovers were of the feminine persuasion, following in the age-old tradition with ships. Not long after landing, the distinctive personalities of Spirit and Opportunity emerged and began to take hold.

Spirit garnered notice as the Drama Queen around JPL, while Oppy was Little Miss Perfect. That’s how Jake Matijevic, a member of the original development team, characterized them many years ago when he was Chief of MER Engineering. The team members viewed the rovers as their colleagues on Mars and actually appreciated their idiosyncrasies, most of the time.

The relationships between humans and robots seemed to progress relatively quickly and the once frowned-upon practice of anthropomorphizing went out the window on this mission. “They were colleagues that became family,” summed up JPL’s Chief of MER Engineering Bill Nelson. “Most of us began referring to Spirit and Opportunity as she’s not it’s,” he said.

Turned out, Squyres’ approach proved incredibly productive not only effectively bonding the dissimilar personalities of engineers and scientists, but also bonding the humans to rovers. All of which had to have had a lot to do with the mission’s resounding successes. The more you care?

The ability to function as a unified whole, rovers included, to serve the greater good of the mission objectives transformed MER into a sum greater than its parts all wrapped up in the gift of the next day on Mars.

Okay, it wasn’t always nirvana. The mission had its fair share of complaining and sniveling and even hot arguing now and again. But after the heated disagreements and decisions-made-but-not-liked, team members usually came around pretty quickly. Drama queens weren’t allowed: there was already one drama queen on this mission and there was no room for any more.

At some point after Spirit and Opportunity had completed their primary missions, I realized these rovers, with this team, had the potential of putting considerable distances of Martian terrain in their rear view mirrors. They were driving past the points of excursions and embarking on expeditions.

It was Squyres, I think, who first used the phrase, but I soon realized I was actually covering humanity’s first overland expeditions of Mars.

In the meantime, even as the scientists and engineers commanding Spirit and Opportunity were rambling across Mars, the clamoring for a human mission to the Red Planet was getting louder and louder. But with these rovers, the humans on the MER team were already there, initiating a new way of exploring, “a new way of projecting themselves into an alien environment,” as Matijevic defined it for me so many years ago.

In other words, Mars was already ‘occupied.’

Throughout the mission, the MER team members pioneered this new method of exploration, and we finally caught up, again, with science fiction. Maybe the mission scientists didn’t hold Martian dirt in their hands, but, with the help of the rovers’ handlers, they were doing on Mars what field geologists do wherever they explore, roving around, taking pictures, and checking out the rocks, terrain, and features of their site.

“We were the first group of people to 'walk' on Mars,” summed up MER Athena Science Team member Larry Crumpler, Research Curator for Volcanology & Space Science at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science.

“People often try to create a big difference between robotic exploration and human exploration, but we are humans exploring Mars with robots equipped with tools,” explained Golombek, who heads the Mars landing site selection team at JPL. “There is a consciousness on Mars,” he said. “It’s a human consciousness, and it’s been there now for a long time.”

Under the leadership of Squyres and Theisinger, and Project Managers Jim Erickson, and, since March 2006, John Callas, the team inaugurated this new way of exploring another planet, along with a way of working and surviving on Mars, getting along during the long hauls, tending thoughtfully to the rovers, and living the motto “every day on Mars is a gift.”

The MERtians uncommon amicability would continue to intrigue me, knowing and having experienced just how different the scientist and engineer personalities are. Yet year after year, I saw a team of individuals doing what they loved and loving what they were doing as a team. Working together, they ended up manifesting one of best work environments for which anyone could ask. The engineers and scientists got along so well that it turned into something of a joke for a while, with engineers at JPL describing team meetings with the scientists as “MER Love Fests.”

Exploring Mars can be exciting and thrilling, and more often it can be tedious and boring and painfully slow, with a rush communiqué to and from Mars taking at the very least 30 minutes. No matter the day or the agenda though, the team consistently honored the MER ethos and showed time and again what teamwork is all about and what amazing things can happen when people work together for a common goal.

Through it all – the fast times, the slow times, the uncertain times, the times of agony and defeat, and the times of victories and cheering accomplishments – I saw a team willing to do whatever it took, to think differently to find solutions or workarounds other teams would be hard-pressed to come up with, to line up outside their boss’ door to volunteer if needed for some mundane weekend task, to review a plan again and again and again to make sure Opportunity would get out of that crater. It was a team always willing to go the distance, just like Spirit and Opportunity.

This was life on MER. And this is how to make great things happen.

For all intents and purposes, the MER mission wrote the manual not only for conducting geology and roving on Mars, but for how to a manage a team of scientists and engineers that ensures everyone gets along. Squyres’ understanding of the intrinsic difference between scientists and engineers and his decision to address it amiably right at the beginning was as gutsy as it was needed and with JPL’s solid project management in place, this culture of unification worked brilliantly.

The MER mission operated with both its brains and its heart, usually simultaneously.

Yet without the tone and direction, the ethos established at the start, and without a work environment where camaraderie, respect, and common courtesy flourished, would the team members have been as dedicated, as willing, and as motivated to rise to all the challenges they did, and would Spirit and Opportunity, unbelievably robust little bots that they were, have persevered and roved for as long as they did?

Everyone who was or is part of the team, even those who moved on to other missions years ago, speaks of MER with a reverence. For those outside looking in, it may seem a little unusual, maybe a little over the top. But the gratitude, always expressed, is real.

“MER was the best family that I have encountered in six landed missions,” said Arvidson, who, with more Martian dust on his khakis than any other scientist, speaks from experience. “This mission stands out because of the management philosophy that integrated the operations teams: scientists and engineers trusted and respected one another, and learned from one another; engineers went the extra mile to make sure the science got done while the scientists learned to be patient when engineering issues arose,” he said.

“The adventure on Mars is certainly be one of the highlights of my career, if not my life,” said Bell. “I can't imagine any of us involved getting another opportunity to experience exploring two amazing, past habitable environments at the same time. And the teamwork, the camaraderie, the sense of family among scientists, engineers, managers, administrators, and everyone who followed along, is a model for international space exploration projects that I hope can be stretched far into the future.”

Beyond space, this scribe would venture to add it is a model that could be adapted here on Earth for virtually any mission or any company. What if corporations, government branches, agencies, and small businesses applied this approach? Just imagine what other humans could accomplish.

It was the people with the right approach and unwavering dedication to their mission that enabled Spirit and Opportunity to do all the “impossible” things they did, not the least of which was putting down tracks to mark humanity’s first paths on Mars.

Along the way, the MER team lost 10 of its own cherished colleagues who contributed so much and who are greatly missed to this day, and one Martian who inspired them throughout the years. In Memoriam

As MER heads toward history, the team members’ sense of commitment, determination, willingness, and gratitude with which they defined this mission keeps them roving on to new missions, new places, and new experiences. But the memories they share from the miracle mission to Mars aren’t going anywhere.

For so many of the thousands of people who worked on the MER mission over the years, the hundreds who make up the MER ops teams, and all the people around the world who have keenly followed the adventure, the reality of never again roving to a new site with Opportunity, the reality of never doing anything ever again with this rover is setting in. Fifteen years is a long time.

Whether ops and science team MERtians have already ‘landed’ on some other mission or are still en route to something different, chances are that at some point in the last month or so, Oppy, and Spirit too, have come around and taken center stage on those quiet moments in the mind. And they’ll come around again.

It’s a given, for there are precious experiences in life where the stars align, everything comes together, and something amazing happens. This mission was one of those precious experiences. For anyone lucky enough, life after MER will never be the same, for every good reason.

Recently I was talking with Jennifer Herman, MER’s Power team lead, who heads to Gale Crater and Elysium Planitia these days to work with Curiosity and InSight. Great places, great missions. “But it is different,” she admitted.

She paused for a moment, and then summed up why in her own heartfelt way. “I feel like I’ve left my childhood home,” she said.

It struck a chord, as it will for so many who hopped onboard this mission so long ago.

MER was of its time. At its simplest it was two places on Mars, two rovers, and a willing group of people on a mission to explore the Red Planet. They took us to Gusev Crater and the plains of Meridiani, and for the first time in human history we got to really rove around on Mars and check out these places up close.

These are the places where we grew up while exploring an alien planet through the eyes of two intrepid robots. These are the places we lost our Martian innocence.

Maybe you can’t go home again. But you can take what you learned, what you saw, what you felt, what you did, and what you dreamed with you. All those who worked on this little mission to Mars during the last 20 years embody the MER legacy that lives among us all.

“We carry all our knowledge forward and have the ability to both impart it to others as time goes on and to carry our lessons into other things we do,” said Squyres.

In coming months, Arvidson and the teams at the PDS Geosciences Node and the Imaging Science and Cartography Node at USGS will complete the preservation of all MER science data and images. Then, at some point, in September likely, NASA will officially close the books, turn out that last light, and the first overland expedition on Mars in human history will be, officially, history.

The sky is turning blue and the Sun is setting. Time to pack it up.

“It ain’t over ‘til it’s over.” Right? That was part of the MER ethos too.

It makes me smile. The team members I know are already paying it forward, galvanizing the legacy of the MER mission that lives on. As for the future that MER enabled? Well, it’s now the present and the future. How about that?

I look at Opportunity one more time and the faint tracks that remain. The “footprints” of the first human-robot convoy from Earth ended right here in Perseverance Valley. That’s something to see alright.

But it’s dusk now. I really must go. Can’t take anything with me, but hey, I can leave something behind. As I squat down and consider the gravelly bedrock canvas before me, there’s only one thought that comes to mind.

I’ll be seeing you

With that, I stand up, close my Swiss Army knife, put it back in my pocket, and say “good-bye.”

Author’s note: As The Mars Exploration Rovers Update Final Report goes to post, I would like to acknowledge the village of people it took to help me produce this mission-long series and keep it going to the end:

- The MER leadership and all the MER scientists and engineers, past and present, who gave me their time and helped me document the mission with their expertise thoughts, and reflections through the years, and all the team members whose unsung efforts informed me and kept the rovers roving and the mission going;

- The scientists and other specialists not on the MER team, but by virtue of their work had insight or perspective to offer;

- The artisans who contributed illustrations, images, maps, and poems, with so much enthusiasm and love for the MER mission;

- The people around the world who logged on every month to spend some time with the latest issue of The MER Update, without who this journalistic voyage may not have survived; and

- The Planetary Society’s executives, past and present, who gave this wickedly long series a forever home, even after it became an anomaly, and each of those individuals at the Society who helped with the production of this series or just cheered my efforts through the years.

The MER Update wouldn’t have been without your support and interest. Thank you. I am grateful beyond measure to every one of you. Now, after 15 years on the Martian roads, I’m taking a break. Then, it’s back to work on my book about this miracle mission to Mars, and other new projects to inform, inspire, incite, and maybe even to leave a few tracks of my own to help make the world on Earth a more thoughtful place.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth