A.J.S. Rayl • Sep 09, 2018

The Mars Exploration Rovers Update: NASA Focuses on Recovering Opportunity as Storm Diminishes and Dust Settles

Sols 5164–5193

The dust raising power of the storms that wrapped Mars in a cloud in June and July diminished in August, sending all that powdery stuff back down onto the surface of the Red Planet. On Earth, the Mars Exploration Rovers (MER) team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) reviewed recovery plans, conducted additional simulations, and began wrapping the month with newfound reasons to believe Opportunity can emerge from her hibernation.

Then, on August 30th, NASA and JPL, home to all NASA’s Mars spacecraft, issued a press release announcing that the MER mission would soon begin “a two-step plan to provide the highest probability of successfully communicating with the rover and bringing it back online.”

Step one will be a period of actively attempting to communicate with the rover by sending it commands through NASA’s Deep Space Network (DSN) antennas. “Assuming that we hear back from Opportunity, we will begin the process of discerning its status, and bringing it back online,” MER Project Manager John Callas stated in the release.

That effort – which could begin as early as September 10th – will last 45 days, according to the press release. If that 45-day effort does not succeed in picking up a signal from Opportunity, a small core group of MER team members would stay on for “several months” more to continue listening “passively.”

Forty-five days is all most people took in. With no live press conference and what read like a rushed out release, forty-five days is what people read and what they spread. The end seemed near. What “passive listening” and that part of the effort actually meant for Opportunity was not explained and was all but lost in furious translation as the story hit the most popular social media sites and science hangouts before moving into the mainstream news.

Over the next few days, there was reaction and confusion about what was going to happen to Opportunity. Even before the dust had a chance to settle on Earth, one thing became immediately clear: this rover is still loved around the world. It also seemed clear that there was more to this story than was being reported or understood.

Since Spirit and Opportunity landed in January 2004, the MER mission has always been a story. During the last 14 years, eight months, and counting, the twin rovers and the MER team have beaten so many odds, overcome so many challenges, made lemonade out of lemons so many times. Now, here they are again.

Mars exploration is never easy. “This dust storm has been a tough ordeal for our rover, and for our team,” MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres, of Cornell University, told me during an interview. “So if we hear from the rover again, I think it’s going to feel like a pretty miraculous recovery. But you could have lost a lot of money betting against Opportunity over the years,” he reminded. “I’m actually pretty optimistic that we’ll hear from her in the coming months.”

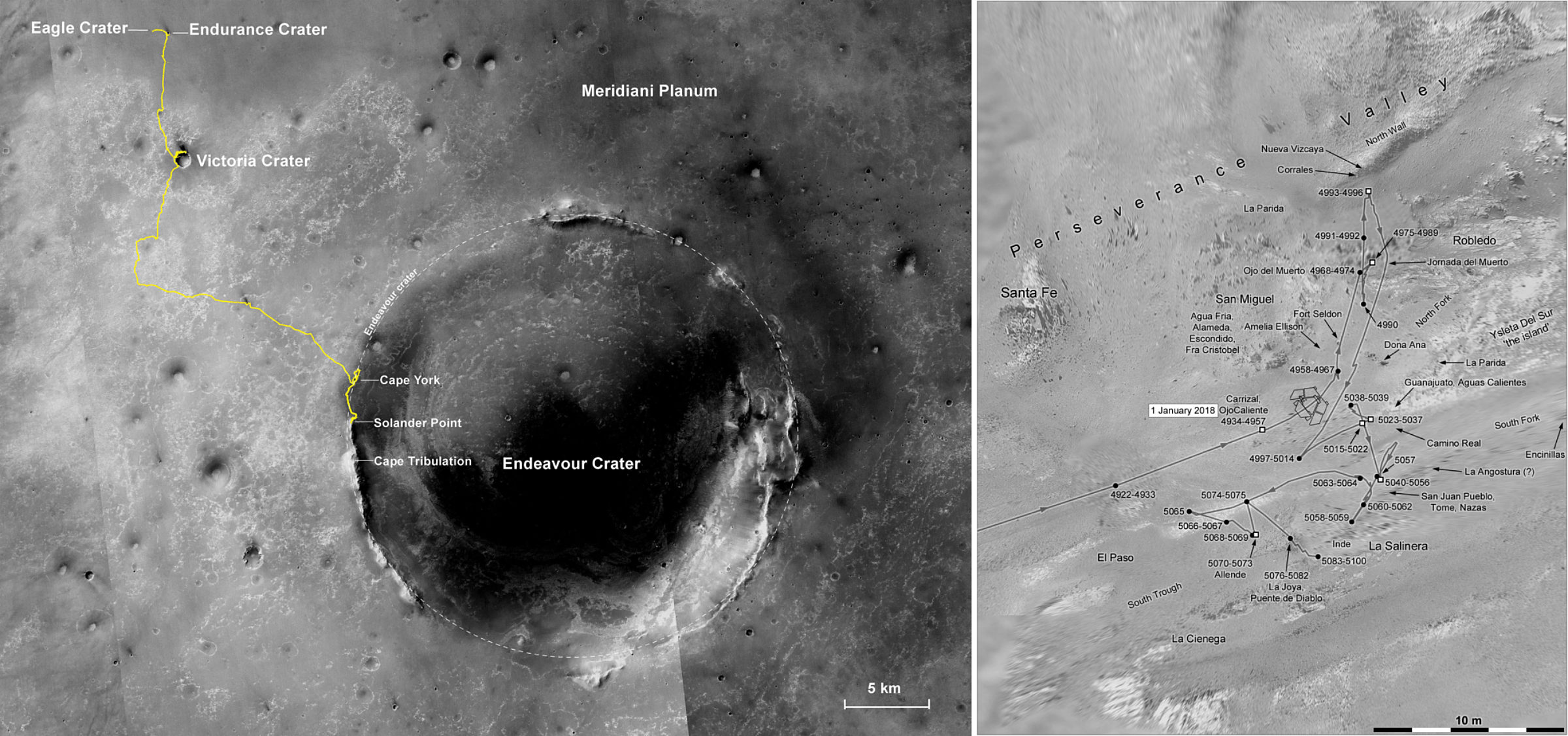

Parked about halfway down Perseverance Valley inside the western rim of Endeavour, the nearly 15-year-old, veteran rover – the longest-lived robot on another planet – remained silent as expected through August, presumably sleeping. While the dust was settling out of the atmosphere and onto the Martian surface, it was anybody’s guess how much dust was settling on Opportunity.

In any case, there was more sunlight streaming through the haze to the surface, and the sky would continue to brighten over Endeavour throughout August. A little sunlight is just what this solar-powered robot field geologist needed.

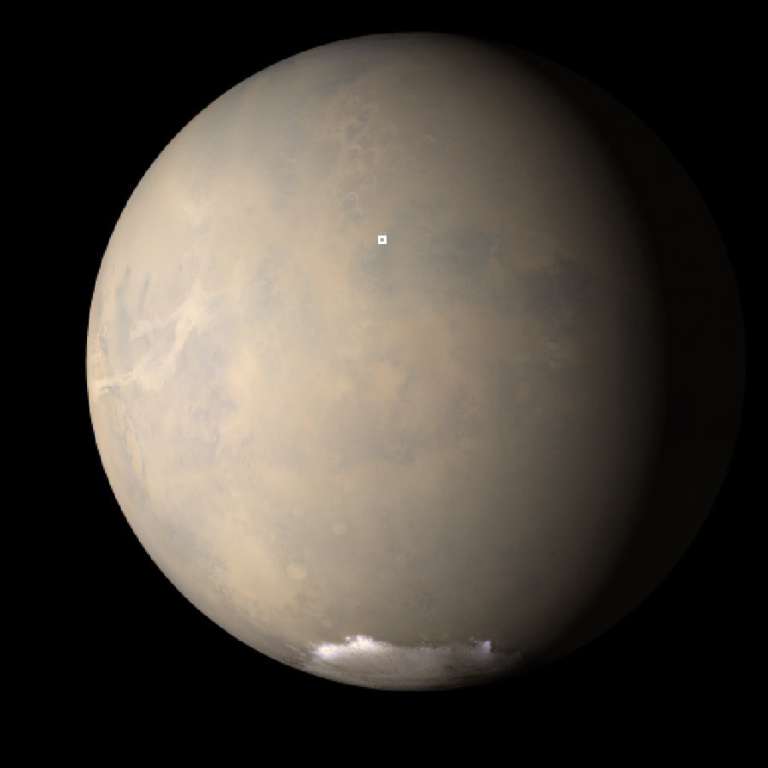

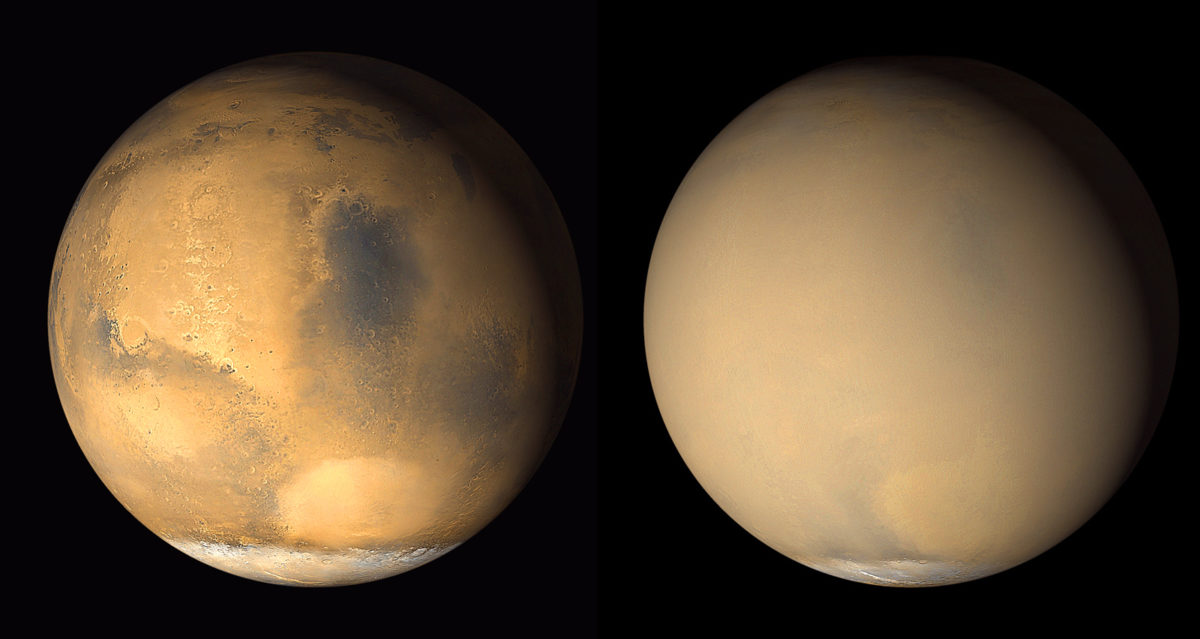

From above, the dust cloud was visibly breaking apart and windows opened onto the rusty red Martian surface below. Cameras onboard Mars Odyssey, the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), and the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN (MAVEN) were once again seeing Endeavour Crater, Olympus Mons, Valles Marineris, and other recognizable surface features. With the Mars Color Imager (MARCI) onboard MRO documenting the decrease in the dust in the skies below, other instruments, including the Mars Climate Sounder, also onboard MRO, began revealing that the atmospheric pressure is returning to non-storm conditions.

“We’re approaching the time in which we would expect a healthy rover, without too much dust on its solar arrays, to be able to recharge its batteries,” Callas said in the days just before the announcement. “We’re listening and we’re hopeful. But understandably, people are concerned.”

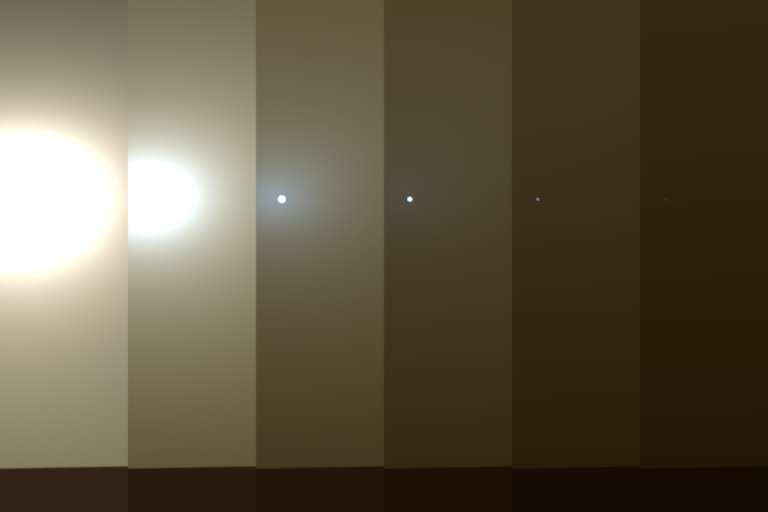

Team members have not heard from Opportunity since June 10th, when they received a message that the dust in the sky overhead, a Tau as the team calls it, was 10.8, the highest the MER mission or any Mars mission has measured. The average range of Tau this time of the Martian year ranges from 0.5 to 1.1, and it has been estimated as high as 5.5 during the planet-encircling dust event (PEDE) that Opportunity survived in 2007.

A Tau of 10.8 turned day to night at Endeavour and forced the rover to shut down into a survival mode of sleep. The MER engineers and scientists dug in on Earth, reviewing, tweaking, analyzing the various possibilities, as well as developing contingencies for even unexpected issues, contributing everything thinkable to recovering Opportunity once the monster dust event was over. From that data, Callas developed a recovery strategy plan that met with the approval of a peer review panel at JPL in mid-August.

Once he addressed NASA’s request to come up with a timeframe, Headquarters approved the revised plan on presentation. When the Tau dips below 1.5 and stays there or lower, the MER ops team will begin the 45-day period of “actively” attempting to communicate with the rover by sending it commands via the Deep Space Network (DSN) antennas. These numbers were derived based on declining solar insolation and decreasing temperatures as the rover moves through summer, according to Chief of MER Engineering Bill Nelson.

With Opportunity still hunkered down in silence, the only viable estimation of dust in the skies over Endeavour would have to come from orbit, specifically Bruce Cantor, of Malin Space Science Systems, who produces weekly Mars weather reports using Mars Color Imager (MARCI) data. With the MARCI imagery and modeling software developed by colleague Michael Wolff of the Space Science Institute, Cantor is able to estimate the approximate Tau over local areas on the surface.

By the time August was coming to an end, Cantor, told the MER team that the Tau over Endeavour had dropped to 1.6, with an error margin of +\- 0.2. That would probably place the beginning of the 45-day active commanding period in the first half of September, and the end some time in late October.

Things getting back to normal on Mars was good news, but the path forward to recovering Opportunity remains cobbled with unknowns and uncertainties, so many unknowns that even trying considering them all is like going down the proverbial rabbit hole. Does the rover have any power? How much dust accumulated on the rover’s solar arrays during the storm? Does the rover know what time it is or did the mission clock fault? How long will it take with the dust on the solar panels to recharge the batteries? Is the rover still capable of waking up?

There is just no way to know anything or calculate anything without data from the rover. Then there are the issues of time and money. “In a situation like this, you hope for the best, but plan cautiously for all eventualities,” Callas stated in closing in the press release. “We are pulling for our tenacious rover to pull her feet from the fire one more time. And if she does, we will be there to hear her.”

Although Callas informed the MER team via email just before the press release went out, “there was an element of surprise,” as one team member at JPL put it. “The surprise was how short the timing is for the active recovery attempts,” said MER Athena Science Team member Larry Crumpler, a research curator at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, and Associate Professor, University of New Mexico.

If no signal is found in that 45-day window, although the project would have to begin reassigning people and downsizing, the passive listening efforts would continue though until at least the end of January, Squyres said. “It’s a good plan. ‘Active listening’ really means trying to send commands to the rover, which is labor-intensive. It’s also probably unnecessary, since the rover should simply wake up and start talking to us on its own if and when there’s enough power,” he said. “Commanding shouldn’t even be necessary. So a fairly short period of active listening to cover all the bases, followed by a longer period passive listening makes sense.”

As Mars would have it, a seasonal cycle of windy months will begin in mid-November and last through January. For as long as MER has been roving, they blow in like clockwork at Meridiani Planum where Opportunity is exploring Endeavour Crater. Those windy months, as it looks now, will occur not during the active 45-days but during the passive listening period.

Still, time, rather the loss of time is of the essence now more than ever. InSight is to land in late November. And there is more on the Martian horizon. Following the final windy months of summer comes fall, the autumnal season when sunlight and temperatures begin to drop into winter, much as they do on Earth.

Will Opportunity be able to recharge her batteries in time to ensure the electronics stay warm before the nightly atmospheric temperatures drop and cause damage? “This is something we worry about right now,” said Chief Scientist of the Mars Program Office at JPL, Rich Zurek, who is also project scientist for MRO.

At the dawning of September, the first robot to “run” a marathon on another planet may still be asleep now, but even when Opportunity wakes up, provided she does, she will be confronting the toughest race of her robot life.

Deep Dive Into August 2018

When August dawned over Endeavour Crater, the last of the lifting centers that had created the huge planet encircling dust event (PEDE) were losing power and expiring, and the ‘storm’ was diminishing into its second, decay phase. The cloud blanketing Mars was breaking apart and the fine, magnetically sticky dust that the storms lofted as high as 60 kilometers (more than 37 miles) up into the atmosphere was beginning to settle out across the planet moved by the Martian winds.

Although Mars has a much thinner atmosphere than Earth, the dust fell essentially the same way as it would on our blue and brown marbled planet. “It’s like Earth. It’s all gravity,” said Cantor. “There’s nothing special happening, nothing unusual that doesn’t happen on the Earth.”

The speed and pace of the falling dust has a lot to do with the size of the dust particles: the larger particles fall out first; the smaller particles float behind. The higher up the dust has been lofted, the longer it takes for the dust to fall back to the Martian ground.

“Typically what happens is there is a fast fallout rate during the first part of the decay phase of the storm,” said Cantor. “While some lifting centers may still be active in this phase, it’s a period when more dust is falling out of the atmosphere than is being lifted into the atmosphere.”

On the other side of Mars, the much larger, nuclear-powered Mars Science Laboratory (MSL), aka Curiosity, rover, was regularly measuring the Tau in Gale Crater. During the first part of August, Tau there had dropped from a high of 8.5 (+/- 0.5) in June to around 2.2, according to MER Athena Science Team member and atmospheric scientist Mark Lemmon, Senior Research Scientist of the Space Science Institute (SSI), who also works on MSL.

As long as Opportunity is hibernating, there will be no data forthcoming from the surface at Endeavour for Lemmon to use to determine Taus. It hadn’t been immediately pressing. The science team wasn’t expecting to hear anything from the rover until there has been a significant reduction in the atmospheric opacity over Endeavour Crater. Lemmon, Cantor, Rover Planner Paolo Bellutta, of JPL, and others suggested months ago it would be mid-September at the earliest that the rover’s ‘phone call’ home might be heard. So far, so good.

Even so, the MER team obviously needed a regular read on the dust opacity at Endeavour to move forward and had turned to Cantor. His orbital-model estimates of Tau, derived with Mike Wolff’s Martian-tuned atmosphere model, actually were the only other ‘game in town.’

“These estimates are different,” Cantor said. “What Mark Lemmon is doing is estimating the actual opacity at the site, from the surface. What I’m doing is trying to model that opacity from orbit as we do with terrestrial, Earth spacecraft. When I get a number, it comes right out of Mike Wolff’s model and hopefully it matches Mark Lemmon’s Tau.”

While the model is only as good as the input, things like properties of the dust and surface, “it does a reasonably good job,” said Cantor. “But the real measurement you want is to look at the Sun from the surface. That’s how you really measuring a Tau,” he underscored. “So when Lemmon gets a number, by golly that’s the number.”

All that noted, with the caveat that the orbital estimated Tau is an estimate of regional and/or local dust opacity from orbit, the field of modeling has been improving in recent years, according to Wolff. It is also now serving real and immediate needs, the results of which are presently playing out on Mars with MER. “It’s the best Tau measurement we have for Endeavour available right now,” said Lemmon, MER’s expert atmospheric Mars Tau scientist.

The Tau at Endeavour Crater in early August was presumed to be floating in the 3.6 range, with a large margin of error of 1, based on what Cantor estimated at the very end of July. Too dusty and dark for a solar-powered rover to get up and work, but a continued drop from the 10.8 Tau high that Opportunity reported to the team on June 10th. That was good news.

There were other signs this storm had ceased its Martian style of fire and fury. “We see some signs in the pressure signature, which is looking somewhat normal enough to indicate Mars is getting on with its life now,” said Lemmon.

On Mars, the PEDE continued to decay, although in fits and starts through the middle of August. The event’s lifting centers had all but petered out and the huge cloud veiling the planet was disappearing as dust kept setting out and onto the surface.

The Tau over Endeavour was estimated at around 2.1 in mid-August, but then it popped up to 2.5, fluctuating like usual in the aftermath of such global dust events. “We’re at the point where there’s no more actual storm activity from this event on the surface,” said Cantor then. “We just have a really dusty atmosphere.”

At JPL, the MER mission ops and recovery preparation forged ahead with research into an additional prong of the recovery strategy, developing contingency plans for more hypothetical but possible Martian scenarios. Understanding it might take time, the MER ops engineers also understood that patience was and would continue to be a virtue. Opportunity could phone home once and it could be a few weeks before she phoned home again. In other words, it may take a little time for the rover to shake off the storm and recover, and it could take several communication sessions before the team has enough information to determine the approximate health status of the rover.

Once Opportunity is communicating with the team on Earth and has powered up to around 250 watt-hours per sol, the engineers will uplink a sequence bundle (including master, submasters and supporting individual sequences), then send a real-time activate command to activate the master sequence, said Nelson. At that point, they will have taken sequence control of the rover. Once in master control, each master hands control to the next master so a new real-time activate command isn't needed.

The engineers will then be able to thoroughly check out Opportunity, beginning with the clock, which they will reset if it’s at the wrong time, and the lithium-ion batteries. They will also command the rover to take images of her body to see where dust might be caked on sensitive parts, and test actuators to see if dust slipped inside, affecting its joints.

In addition to the clock fault, Opportunity is presumed to be in two other "fault modes” tripped when the rover automatically shuts down to maintain her health. The assumption is that the robot tripped a low-power fault shortly after sending telemetry received on June 10th, and an uploss fault, when the uploss timer timed out in early July, as reported in last issue of The MER Update. In the fault hierarchy, the engineers would address the uploss fault next, because it is linked to the UHF antenna, and then, the low power fault.

Provided all that goes well, the rover, Mars willing, will be off and roving. But this is Mars. Anything can and could have happened. The state of the rover and her systems and instrument is a complete unknown. There is the chance, after nearly 12 weeks, the team may hear nothing or the rover may wake up and for some reason not be operational. “There is just no way of knowing anything really about the rover, other than Opportunity is still there, because we can take pictures of it from orbit,” said Zurek. Actually, word is there is a plan to schedule the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera onboard MRO for imaging Opportunity sometime in September, when MRO orbits around Endeavour.

On the other hand, the unknowns on Mars don’t change the simulations and the power and environmental modeling data produced on Earth. There are sound scientific and engineering reasons for team members and officials to still be optimistic.

MER engineers, for example, performed studies on the state of the rover’s batteries before the storm, as well as reviewed and re-ran temperature models for Perseverance Valley into next year. "The batteries were in good health before the storm," said MER Power Team Lead Jennifer Herman. “It is possible that they sustained damage during the dust storm, but I don’t believe it could have been enough degradation to be mission-ending,” she said.

As for the rover itself, because dust storms tend to warm the environment – and the 2018 storm began as the rover was entering the Martian spring – the ‘bot and her instruments, according to the models, should have stayed warm enough to easily pull through. Nothing has happened since, that the team knows of, to change that thinking.

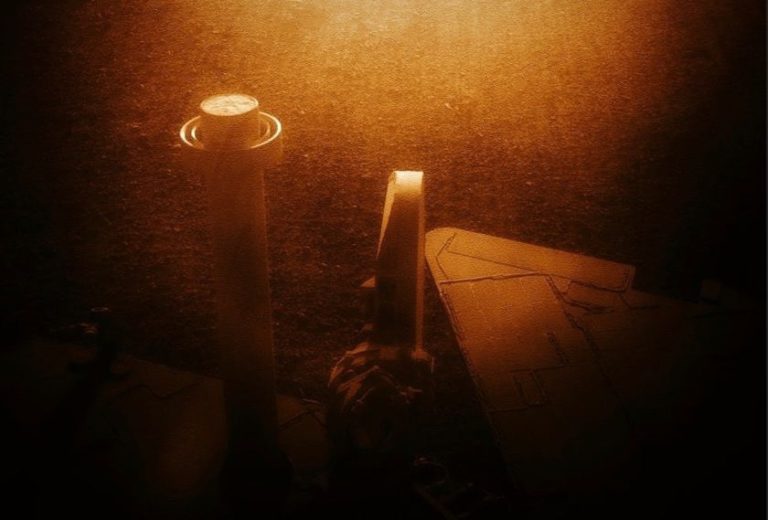

Prior to the storm, Opportunity was fairly clean, producing ample amounts of energy around 650 watt-hours out of a total capability when she was new and pristine of around 905-950 watt-hours. She was in good shape. Then the storm hit Endeavour somewhat like a blinding blizzard on the Dakota plains, where the snow is carried sideways as well as down by the winds. Nearby lifting centers lingered around Endeavour churning up dust for several sols or Martian days.

Once Opportunity shut down, the MER operations team didn’t just sit around waiting. “We’ve been working hard, even before we lost contact to explore every possibility for recovery,” said Rover Planner Ashley Stroupe, who holds the distinction of being designated the first woman driver on Mars. “We are genuinely dedicated to making the most of this priceless asset because that is our responsibility. In recent weeks, we have been looking into how the rover will behave under these previously untested conditions, and we’re ready.”

Most of the MER scientists with expertise on Martian dust and dust storms believe that Opportunity is most likely dirty with dust. “The dust that was in the atmosphere there had to go somewhere,” said Lemmon. “It’s now, 75% or so, on the surface, and the rover’s solar arrays probably got their share of it.”

The team’s last measure of dust accumulation, on Opportunity’s Sol 5107 (June 6, 2018), was .65, meaning 65% of the light on the solar arrays could penetrate the dust layer. The Tau was 4.9 that sol, but the engineers also know the Tau rose to 10.8 by Sol 5111, (June 10, 2018). “It took a lot of wind and dust to cause the Tau to rise from 4.9 to 10.8,” said Herman. “We don’t know if any of those winds at any point cleaned some of the dust off the solar arrays – that’s possible. It’s also possible the winds just blew more dust on to them."

Since MER team members have no idea what happened or any data from Opportunity since the June 10th communiqué, they have no idea how dirty the solar arrays are. “That can give the impression things are very grim, but it doesn’t necessarily mean they are,” said Herman. “From past history, we know the rover will need a dust cleaning.”

Lemmon agreed. “Opportunity couldn’t have ended up much cleaner than it was to begin with,” he offered. “And I think there is a chance that if we don’t hear from the rover immediately after the dust clears out, we’ll need those Martian winds to clear the solar arrays.”

Time, this time just may be on Opportunity’s side. “Things are only improving,” said Cantor. “It’s still not great for Opportunity, but the general weather patterns are improving, the atmosphere is warming, and the winds will be coming. It’s all positive for this rover in the next few months, and I think the rover’s going to come back. I would be shocked if it didn’t.”

MER ops team members continued to listen every day in August, either during expected fault communication windows or over a broader range of frequencies and times using the DSN’s Radio Science Receiver (RSR). No signal from Opportunity. No surprise.

Even so, by mid-August, it had been 10 weeks and there was angst in the air – and yet everything seemed on track. Everyone seemed status quo: cautiously, genuinely optimistic.

Since Opportunity shut down in June, Callas and other MER officials had been working on a strategy to reconnect with and recover the rover. Director of the Mars Program Directorate at JPL, Fuk Li, who was there for the spectacular, globe gripping landings of Spirit and Opportunity, commissioned an independent peer review of the MER team’s strategy for recovery. It was a review panel made up of “people with expertise,” at JPL “who could be helpful,” said Callas.

As the second week of the month came to an end on August 14th, Callas presented the three-phase plan, outlined in the last issue of The MER Update. “They thought we did a thorough job of developing our strategy and investigating our possible fault modes and methods of recovery,” he said afterwards.

With a few recommendations Callas acknowledged were already accepted into the team’s strategy, it was on to NASA Headquarters for approval. Before that meeting would take place though, he was tasked with a specific directive.

The Mars Exploration Program office at NASA Headquarters wanted a projection of how long the MER project would consider it reasonable to attempt to communicate with Opportunity, and what a possible timeline would be for winding down the project if the rover didn’t respond.

“I was asked by the Mars Program to establish the criteria and the duration by which we feel that we have done due diligence in trying to listen and recover the vehicle,” Callas told The MER Update. “If at the end of that time we haven’t been successful, if we haven’t heard from the rover in that time, then we will begin project close out. That’s what I was to develop.”

Meanwhile, on August 16th someone checking out the Deep Space Network Now boards had spotted a carrier signal thought to be from Opportunity. It was accompanied by animation believed to be an indication the rover was phoning home. The excitement only lasted an hour. Doug Ellison, Engineering Camera Payload Uplink Lead at JPL, clarified: it was a false alarm.

Around that time, members of the MER ops team started hearing things about Opportunity and a NASA plan to end it all. The chatter of numbered days and EOM – meaning end of mission in the acronym world of NASA – went viral at JPL according to those interviewed there who found themselves in the loop.

A group of engineers approached Callas about what they were hearing, wondering if it was true. “I talked with some of the people involved and each one had a story that differed from the previous one,” he said.

On August 22nd, Callas sent an email to the team. He told them of the request from NASA HQ and that he was working on an assessment of when power levels should be sufficient for an expectation of Opportunity to be capable of communication. “No one wants to put a limit on our hope. But it is something we must do,” Callas wrote. "For right now, let's focus our attention on recovery and doing all we can to listen for Opportunity,” he advised. “She needs us to be ready."

It was a welcomed email. “Opportunity has been amazingly resilient and we've learned to no longer be surprised when she pulls off ‘miracles’ thanks to the brilliant engineering behind her,” said Stroupe. “I believe the operations team’s responsibility to science and to the public is to make every possible effort to recover the vehicle. If our models and projections are right and it is at all possible, we believe we can do this.”

Figuring that their project manager needed the absolute best science and engineering data support, members of the MER ops team began revisiting everything – again models, projections, historical data, and records. It was a natural thing for them to do, having done it many times before on MER to address this issue or that, because Opportunity and the engineers have been after all, always roving in new territory.

Herman had already planned to run some additional energy simulations with dustier solar arrays. With Nelson’s approval, she did that and presented the data, results, and ideas for strategies at the engineering meeting on Thursday, August 23rd.

Lemmon, meanwhile, was reviewing Tau data both and comparing Cantor’s orbit MARCI-modeling estimates at Gale with his ground estimates for comparison. “Cantor’s orbital estimates are consistent with what we’re seeing from MSL at Gale,” he said. Extrapolating, that would indicate, he agreed, that Cantor’s Tau estimates were probably consistent with what the dust opacity is at the time at Endeavour too.

As unpredictable as Martian weather can be, there are times when it is predictable sometimes. “We do have this history of seasonal cycles of winds, when dust cleanings happen at Meridiani and we do know windy months follow southern summer solstice,” said Lemmon.

Part of what Herman did was to go back and review the mission’s dust and power history through the different Martian seasons. The windy cycle, according to the MER mission’s historical data, is slated to begin in mid-November [Ls 290] and blow through January 26th, 2019 [Ls 330], and it sometimes stretches to the southern fall equinox, which comes up on March 23, 2019.

“Every single year that we’ve been on Mars – all seven previous Mars years of data – we have seen dust cleanings in this timeframe,” she said. “It doesn’t matter if it was the year of the PEDE in 2007 or the year we had a regional storm that got Tau up to 2 or a calm year."

Herman also conducted some new simulations. Every one indicated the same thing. “In order for us to hear from Opportunity, we need the solar arrays to be fairly clean, able to take in and utilize at least half of the sunlight hitting the solar arrays,” she said. However, according to the historical records, there is a good chance the rover will get that needed dust cleaning, but it may not be in the next 45 days.

Meridiani is a dusty area. From July through the southern summer solstice on September 16th, the rover is most likely taking on dust from the fallout. “The historical pattern shows this is a time of dust accumulation,” Herman said. “It’s typical for this time of year, whether there is a dust storm or not, to see some accumulation. Then, once past the summer solstice, the mission has historically started to see the winds cleaning off the solar arrays again,” she said corroborating what Lemmon had noted from memory.

Mars weather history seems to bode well for Opportunity. “We need dust cleaning,” Herman said, agreeing with both Lemmon’s and Cantor’s assessments. “We don’t know what the magnitude of the dust cleaning will be – if it will be enough – but knowing that we’ve gotten some amount of dust cleaning every year at [this] time gives me reason to hope.”

On August 29th, Callas, with JPL’s Mars Program Office Director Li, presented the team’s plan to NASA HQ. Director of NASA’s Mars Exploration Program at the agency’s headquarters in Washington DC, Jim Watzin accepted the “recommendations” as presented and approved the plan for the team to begin actively listening once the Tau dipped to 1.5 or below consistently, or for a few sols.

The following afternoon, Callas informed the team via email that NASA had accepted the Tau 1.5 / 30-45 day listening plan. The NASA/JPL press release announcement followed promptly, published on NASA and JPL websites.

At first blush, there would seem to be a little wiggle room in the 45 days of active listening. If, for example, contact is established near the end of that 45-day limit, it would be logical to think that the team would be allowed to continue recovery even if they cross the limit. And if contact is established right after the 45-day period ends? “We can and will evaluate as we go along,” assured Zurek.

The story hit the news flows almost immediately. Supportive wishes, ‘Help Oppy’ pleas, thank-yous, and suggestions and opinions popped up on Twitter, Instagram and other social media hang-outs, as viral movements, like #SaveOppy and #WakeupOppy, roved through those sites and others. News stories also began to appear on nationally known magazine websites, ranging from The Atlantic to Popular Mechanics.

Pertinent and important details, however, were missing in the real news action, not to mention the tid-bytes passing through social media. With today’s rapid-fire, almost hourly news cycles, facts and details frequently go AWOL or wind up spun in another direction or are simply misunderstood especially with science stories.

So what is passive listening? And does it make re-connecting with Opportunity more difficult?

“These months of passive listening represent a serious effort,” said Squyres. Just because the team will shift from active to passive listening doesn’t mean the effort will be any less serious, he said.

“A lot of people don’t realize that when we had the campaign to listen for Spirit, that campaign was active listening the whole time, because of a mistake in the fault protection settings,” Squyres elaborated. “Things were set such that if the vehicle woke up it would shut down again before it had a chance to do anything. So the only way to get Spirit to communicate with us was to – at a time when we thought it would be awake, hit it with a command that would tell the rover not to do that. It was the only way to listen for Spirit,” he said.

“That is not the case with Opportunity,” Squyres continued. “With Opportunity, in passive listening, all we have to do is listen,” he said. Even if nothing is heard at the end of January, the principals on the mission, at JPL and NASA will undoubtedly regroup and, as Zurek said, “evaluate” next moves at that point, he added.

Much of the uncertainty in the media rush could be tracked back to the brevity and terse wordage of the press release, previous chatter within the Mars community, and social ‘word-of-mouth’ suppositions.When the news begs for details and there are few, that keeps understanding at bay. The instant take-away, for all intents and purposes, was Opportunity is not being given a fair chance.

The immediate media reaction, however, also got people thinking – and remembering.

There has never been a mission like MER before and there won’t ever be one again. “You can only do something first, once,” as Squyres put it long ago. The dust is settling, Opportunity is there in Perseverance Valley, and the MER team is still roving.

Everyone on the ops team is at work preparing to re-establish communication. If nothing is heard by late October or early November, then the team will be downsized, as the plan is now. If the rover phones home in the passive listening period, you can bet JPL won’t be at a loss for engineers eager to return with helping get her back online and roving. Right now though, it’s one step at a time.

The other thing that emerged from the media frazzle is that people really do care about Opportunity. MER, after all, took the world by storm as 1.2 billion people – then one-fifth of the global population – jamming NASA and JPL mirror sites within the 72 hours following Spirit’s jaw-dropping landing on January 3, 2004 PST, just to get a look the first “postcards” the rover sent home. Since then, simply summed up, the MER mission has defied all human and robot odds and records.

From a cultural perspective, children have grown up with Spirit and Opportunity on Mars, and WALL-E, the cute little robot ‘toon they inspired. The twin rovers have taken us to hauntingly familiar landscapes on Mars and taken us when no humans can go, yet – and for free to anyone with a computer and web access. They have endeared people of all ages in every pocket of every land on the home planet. You can see it in their eyes and hear it in their voices, whether the conversations take place in Pasadena or New York City, or Tucson or London or Berlin or in the Shandong Province in China. Nobody wants this rover to just be left in the dust.

Once the rover is able to charge her batteries and phone home, recovery can begin. “Anything above 24 to 40 watt-hours a day, which is sort of what the parasitic loss will be to the electronics, will go into charging the batteries,” Callas said. “So wake up Opportunity!”

Despite rumors and suppositions of all sorts, NASA has no desire to just “pull the plug” on this heralded Mars pioneer, Zurek said. Remember, he noted, NASA tried to reestablish contact with the Phoenix lander after a Martian winter when there was virtually no hope it could survive, and it did search for Spirit for 15 months.

“Opportunity has enabled us to explore and go to new worlds and be there virtually in a way that’s hard to do by any other means,” he added. “You can’t do it with ground-based telescopes and orbiters can’t put you into the scene the way the rover can. That matters.”

Nobody believes that more perhaps that the MER team. Squyres imprinted the MER mantra on landing: ‘Every day on Mars is a gift.’

And every day for five years, 10 years, 14 years and 8 months and counting, the members of MER have taken that to heart. Their commitment to the process of engineering and doing science on Mars, an approach the MER team has uniquely developed as a team over nearly a decade and a half with that mantra always in mind is how MER flourished. One factor that led the way was the freedom to speak out, throw all those ideas “no matter how crazy” on the table, as Squyres put it, harkening back to the approach Chris Kraft and other NASA directors used in the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs that got us to the Moon.

When scientists and engineers joined the MER team, they were not only encouraged, but expected to stand up when they felt strongly about something and assured “no judgment.” Moreover, they were given the platforms to do that regularly, multiple times every week, sometimes every day in science meetings, engineering meetings, and end-of- sol tag-ups. The approach united a group of once disparate scientists and engineers and put them on the same page, turned them into friends [imagine] and enabled them and their charming, masterfully engineered robots with human-like personalities to make “miracles” happen – not to mention rewrite textbooks, introduce Earthlings everywhere to our neighbor Mars, and pave the way for future missions.

Throughout the years of roving Mars, the trials and tribulations and emergencies, beginning with Spirit’s “freak-out” right as Opportunity was heading in for her bouncedown in 2004, this team has rewritten the book on “teamwork” and garnered a reputation for being able to “workaround” and fix almost anything -- from tens of millions of miles away. They have come to know and understand Opportunity, and previously her twin Spirit, inside and out and grew into a cohesive, ‘well-oiled machine’ in part because they made decisions together. It was all for the rovers and one for the rovers, and there isn’t a one among them who doesn’t express deep gratitude for the gift of being able to go work on Mars everyday.

As with everything in our material world however, money factors prominently into the equation that appears now to be numbering Opportunity’s days. To keep the MER tactical team intact and at-a-moment’s-notice ready costs about $1 million USD a month these days. “Nobody wants to say good-bye to Opportunity, but NASA isn’t paying us to just wait around,” said Callas. “That would not serve the agency or the public. Those are issues that I have had to wrestle with,” he said.“

“Other people have different desires,” he acknowledged. “A lot of very concerned and passionate people want to squeak out every possible chance to listen for Opportunity. But we can’t just hang on forever. We have to come to a point where we say, ‘Enough is enough.’ That is what I was asked to do.”

These are among the toughest times in planetary exploration. Callas was under pressure “to plug a financial drain,” according to a source with knowledge of the situation. “His numbers are technically defensible, if not technically optimum. And they are reasonable and acceptable to people whose concern is the money.”

As Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis is wont to say: “It could be worse.”

In many ways, with their increasing number of crackerjack spacecraft, NASA and JPL are victims of their own successes. No one, no one in 2004 would have ever dreamed Opportunity would still be roving more than 14 years past her primary mission. The unparalleled success of the twin MERs helped underscore the importance of NASA’s Mars Exploration Program and pave the way to now. This little golf cart size rover is the giant on whose shoulders Curiosity, InSight, and Mars 2020 stand.

Those who’ve been around space exploration do understand the budget reality; they have all been here before. Younger team members are learning. But there has never been a mission quite like MER: there is a pretty deep attachment among team members and their ‘bot to be sure. Although Opportunity is smart enough to do a lot of things on her own, this rover has never gone it alone on this adventure.

Every day for 14 years, 8 months and counting, the MER operations crew on Earth goes vicariously, through technology, to Mars where they have worked and tended to the rover and her needs as a robot field geologist. “We have never just clocked out at the end of the day on this project,” said Herman. “Opportunity is in our thoughts when we go home. Opportunity is alive to us.”

Not being involved this time, not being able to throw all those ideas “no matter how crazy” on the table during a critical decision-making process involving the fate of their rover – the ‘colleague’ for which they have been responsible and which has been a part of their lives, every day, for however many years they have been on the mission – is something this workaround team had never experienced.

Put another way, they have been this rover’s first responders and with Opportunity’s fate is at stake, well, she is one of the most experiments of all on this mission. “Having the chance to ask questions and make comments is important in the world of science whether you have any valid input to the process itself or not,” explained Crumpler.

Actually, the bond formed between humans and machines on MER has been cited as a reason this team remains as dedicated to this little golf cart sized rover as they were on Day One. To not understand that is to not understand the emotional structure of the human machine.

“Opportunity has taught us so much about Mars already, covering a larger range than any other surface mission to date,” said Stroupe. “But we have so much left to do, and a lot of great science discoveries remain to be made in this unique geological area of Endeavour Crater.”

It’s not just the team members. People out there around the world have formed their own bonds and memories too. One of the creators of Opportunity and Spirit, their Chief of MER Engineering for a number of years, Jake Matijevic, eloquently framed it for this journalist late one night after a long day’s work many years ago as we talked about how this team is pioneering a new kind of robot-human exploration. “These rovers are more than tools. They are an extension of us,” he said. “They are us out there exploring Mars.”

There is no way to tally all the people, all the children who have been moved and inspired by Spirit and Opportunity over the years, no way to encapsulate the sheer thrill of turning on a computer and going to Mars for the first time. People remember gifts like this, because they keep on giving.

On Mars, Opportunity’s situation on Mars remains volatile. It’s springtime heading into summer in the southern hemisphere of Mars and that means, yes, it’s still storm season. “But it’s been so dusty this year, we’re not getting a lot of those larger storms,” Cantor said, “and that’s typical following a PEDE event.”

Never say never. It happened before on Viking, a dust storm double header. Moreover, routine smaller dust storms will start kicking up again soon. “When Mars goes back to business of pumping more dust into the atmosphere, that’s the real sign that this PEDE is done,” said Lemmon. “Dust storms die off because the surface loses heating and there’s no energy to drive the lifting center. Once the surface gets back to the point where local storms can pop up and die, and pop up and die, we are in a post-storm situation. It sounds bad in one way – more storms coming – but more storms means more surface winds, and that’s going to be a really good thing for Opportunity.”

“In fact, we’re starting to see some local events here and there, even with this higher opacity generally across the planet,” said Zurek. “We just need a good breeze.”

In a perfect world?

Listen to March 23, 2019, the southern autumnal equinox, or even out to October 8, 2019, the southern winter solstice, suggested team members who were asked. “We do know something about the windy periods and I think that the wind input needs to be paid attention to,” offered Lemmon. “While we are aware that the longer we go without hearing from the rover the more there is a chance for unpredictable problems, if at the end of September we haven’t heard from the rover, that doesn’t tell me that the rover isn’t functioning.”

As August was setting, Cantor input MARCl imaging data into Wolff’s model and estimated that Opportunity should be taking in a little more than 50% of the sunlight reaching her arrays, depending of course on how much dust was coating them. Herman’s energy simulations suggested that dust factor must be 0.5 or less, because we have not yet heard from Opportunity. “My intuition is that it’s more like 0.3 dust factor, but I don’t know what it actually is besides 0.5 or less,” she said.

“We’re all guessing here, because we just don’t know how much dust is on the solar arrays,” reminded Nelson.

When and if Mars will rustle up a dust-guster and clear Oppy’s solar arrays, no one can predict. The rover is, however, positioned well in Perseverance where Martian winds in Meridiani tend blow up from the crater floor. In fact, the rover enjoyed many cleanings earlier this year. It’s just a matter of timing, the planet’s muster, and, now, the health of this five-star Mars explorer.

It ain’t over ‘til it’s over. Yankee philosopher Yogi Berra has often been famously quoted around MER halls and in electronic scrolls of The MER Update. And it ain’t over yet.”

Earlier in August, Cantor predicted the Tau over Endeavour will likely drop to or below 1.5 during the first week of September. And, as September took hold, his estimate was 1.4 +/- 10%.

Word circulated that the team would soon begin the active commanding and listening phase. The MER engineers are thinking that at least 50 percent of the sunlight shining down on Opportunity or more has to be penetrating the dust on the solar arrays in order for the rover to produce the energy she needs to wake up and phone home. “As of now, we think the rover needs a dust factor over 0.5 to generate around 250 watt-hours of energy,” said Nelson. “At a Tau of 1.5 and a dust factor of 0.55, we'd be just above the minimum with 274 watt-hours per sol.”

“What the rover needs now is for the skies to clear and a dust devil to clean off its solar arrays,” said Cantor, as he headed out for the weekend. “I wouldn’t be spelling gloom and doom for Opportunity just yet.”

The stage is set. A plan is made. A movement is afoot. And the world waits.

“It’s always a mistake to say it’s been a long time, that’s good enough,” reflected Lemmon. “You should always look at what the rover is capable of. Steve Squyres is the source there. We’ve got a rover in a great place and we’ve got some good stuff we can still do if the rover responds. If we can get the rover back, we don’t want to waste that opportunity, literally.”

With that unavoidable kind of unknowing hanging in the air, the MER team has refocused now and is working on everything possible to connect with Opportunity and recover the mission’s intrepid rover.

“In the end,” Squyres said, “you can be sure we will do the right thing.”

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth