A.J.S. Rayl • Jul 02, 2017

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Sprains ‘Ankle’ but Perseveres on Walkabout

Sols 4747-4775

The autumn skies over Endeavour Crater remained hazy as dust from the summer storms continued to rain down, but Opportunity encountered some unexpected and serious June gloom when her right front steering wheel jammed during the walkabout atop Perseverance Valley. Although the rover’s “sprained ankle” slowed the pace of the Mars Explorations Rovers (MER) mission for a couple of weeks, the veteran robot field geologist astonished her human colleagues on Earth and roved on.

More than 12-and-a-half years ago, the steering actuator for Opportunity’s right front wheel jammed and stuck in a toed-in position of about 8 degrees and she has driven with it like that ever since. But when the rover was making a basic arc back maneuver to turn on June 4th and the steering actuator for her left front wheel stalled and stopped with the wheel toed-out 33 degrees, it cast a pall on the mission team at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the birthplace of all NASA’s Mars rovers, as well as team members around the world.

“Little Miss Perfect,” as this rover came to be known way back when, showed her MER mettle yet again. After a series of tests and straightening attempts – with, of course, a lot of help from her engineer colleagues on Earth – Opportunity succeeded in straightening that wheel on June 17th.

“It was miraculous,” said MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres, of Cornell University. “We could have operated the vehicle with the wheel cocked off at that crazy angle. But it’s terrific news, just wonderful news and the vehicle will be much easier to operate with that wheel pointed straight.”

When the telemetry confirming Opportunity’s wheels were all straight arrived on Earth, it was Father’s Day and a gift like no other for the thousands of “fathers” who helped put this rover and her twin, Spirit, on the Red Planet and roving along on NASA’s first overland expedition of Mars. It seemed to prove, too, just how much this rover really loves to rove.

Still, it’s not all good. No one, even the best Mars rover engineers in the world who tend to Opportunity know exactly why the actuator stalled or how they managed to get it straight again. They formed a tiger team of current and past MER ops engineers to further investigate. Until then, they are driving the rover in a cautionary mode, concerned that this incident could be an omen, a heads-up that the rover’s wheel actuators are suffering the strains of aging.

So while Opportunity roves on, things have changed. "For at least the immediate future, we don't plan to use either front wheel for steering," announced MER Project Manager John Callas, of JPL, on June 23rd.

“Whatever went wrong with it and whatever we did to straighten it, the steering wheel actuator is still not ‘healthy’ and the problem is only mitigated,” said JPL’s Chief of MER Engineering, Bill Nelson, “The wheel is straight now and we can steer the vehicle, but we’re not willing to steer the wheel itself. We’re not going to mess with it.”

Those unfamiliar with the rocker bogie and wheel systems of Spirit and Opportunity might view this as a rather significant conundrum. But, as reported in these pages many times over the years, these rovers were built to last and with a significant amount of redundancy.

Of the MERs six wheels, four – the two on the front and the two on the rear – were designed with both steering and drive capabilities and so each of those wheels boasts two actuators, one for steering and one for driving. The steering actuators turn the wheels back and forth, and the drive actuators turn the wheels round and round.

"We can steer with two wheels, just like a car, except it's the rear wheels,” Callas said.

Driving backwards is something that Opportunity has been doing for years now to keep her stuck right front wheel from getting “overheated,” or, technically speaking, to keep the steering actuator current levels from getting higher than desired. So steering with her rear wheels isn’t a monumental change for the veteran rover. As for turning, well, the rover manages that now by adapting to the way tanks turn, “where you drive all the wheels on one side in one direction and all the wheels on the other side in the other direction,” said Squyres.

Opportunity wasted no time getting back to making tracks on the walkabout, surveying rocks and geological features in the area just above Perseverance Valley for signs that they may have been either transported by a flood or eroded in place by wind.

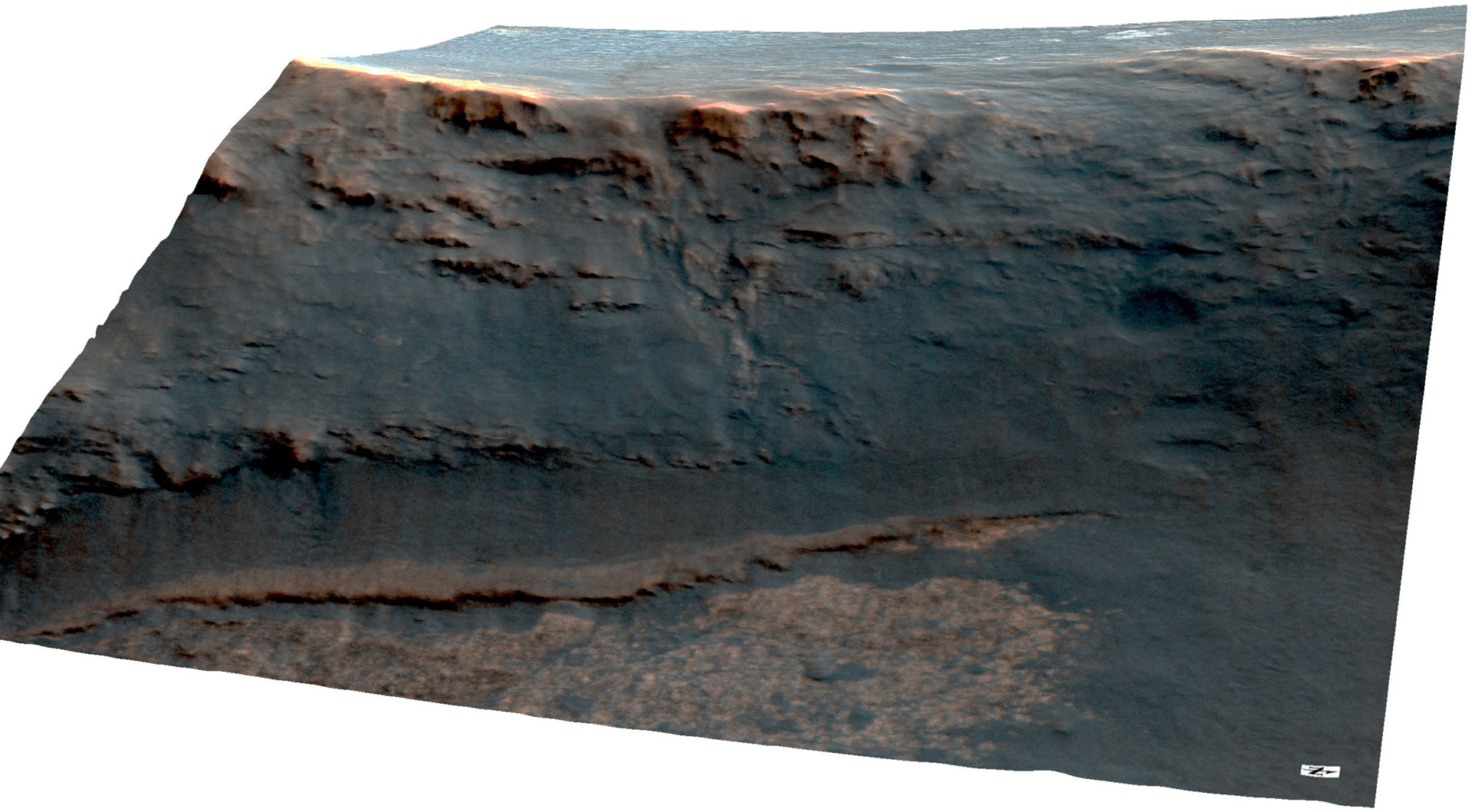

"The walkabout is designed to look at what's just above Perseverance Valley," said MER Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis. Just west of the broad notch at the crest of Endeavour Crater’s western rim, the entryway to the valley, the rover has returned images of a large, shallow channel or trough within “a pattern of striations running east-west outside the crest of the rim,” he said.

The large channel or trough in this east-west swath of ground – which may have been a drainage channel or spillway billions of years ago – is lined with rocks that the MER science team is particularly interested in. “We want to determine whether these are in- transported rocks or in-place rocks," Arvidson said.

"One possibility is that this site was the end of a catchment where a lake was perched against the outside of the crater rim,” continued Arvidson. It could be that “a flood might have brought in the rocks, breached the rim, and overflowed into the crater, carving the valley down the inner side of the rim.” That would mean the notch in the crater rim crest just above Perseverance Valley would have been a spillway. Weighing against that hypothesis however are the rover’s images that show the ground west of the crest slopes away, not toward the crater. The science team is contemplating possible explanations for how the slope might have changed over the last few billion years.

Another possibility is that the area was fractured by the impact that created Endeavour Crater, “and then rock dikes filled the fractures, and we're seeing effects of wind erosion on those filled fractures,” said Arvidson. Rock dikes are a type of vertical rock in between older layers of rock. A variation of this impact-fracture hypothesis is that water rising from underground could have favored the fractures as paths to the surface and contributed to weathering of the fracture-filling rocks.

At this point, those scenarios are the leading working hypotheses that the MER science team is testing for how Perseverance Valley formed, how it was carved into the inner slope of the crater rim.

After straightening her left front wheel, Opportunity, still undaunted, roved on and got back to looking for clues. The robot field geologist worked on completing close-up and landscape visual examinations of various rock groupings, as well as the length of the rock piles along the edges of the channel or trough. The images she returned to Earth should contain clues, maybe even the hard evidence that the scientists need to add to the story of past water at Endeavour and perhaps define ancient environments.

Using her rear wheels to steer and turning like a tank, Opportunity impressed her human colleagues and handlers, although she is on pretty solid terrain that makes for good roving. “So far, the path we have followed is showing the rover is working great,” said Rover Planner Paolo Bellutta, who has been charting the rover’s routes since Victoria Crater. “The driving capability is not too bad. Oppy being the indestructible little rover is still driving around fine,” he said. “I think that partly is because we can't see how much stress the new driving strategy causes to our teenager, but the telemetry still looks fine.” Rocky or sandy terrain however could present greater challenges.

As June wound down, Opportunity drove through the channel and to the northern “wall” of the area atop Perseverance Valley, her fifth and final waypoint on her walkabout. The rover will be spending July 4th – America’s Independence Day – working as usual, shooting more images of the shallow depression or channel that she’s in, and the northern “wall,” to complete “a nice mosaic of the northern side of this features,” said JPL Deputy Project Scientist Abby Fraeman, who 14 years ago was a Planetary Society student astronaut on the mission.

The MER team experienced an “exciting” two weeks,” said Fraeman. “But it ended with “relief and joy. Once again, the rover has continued to amaze us.”

The team however is facing other challenges. With summer on Earth being the time of vacations and with various MER rover planners and engineers working Curiosity and/or other missions, MER is short-staffed.

On top of that the Earth-Mars solar conjunction is just around the corner. This celestial event occurs every 26 months or so when the orbits of Earth and Mars place them on opposite sides of the Sun, making communications between the two planets so risky that all Mars missions institute a two-week communications blackout period. So Opportunity will be incommunicado from the latter half of July into early August. Not long after that, the solar-powered ‘bot will need to hunker down on a nice north-facing slope, ideally inside Perseverance Valley, where she can soak up as much of the winter sunshine as possible for the mission’s eighth Martian winter so she can continue to rove and work throughout the harsh season.

The moratorium on using the left front wheel will make precision close-up science investigations with the Instrument Deployment Device (IDD) more difficult in coming weeks and months. “While there will be added challenges, we don’t think they are insurmountable,” said Fraeman. “We’re optimistic that we’ll keep on roving and make it through winter.”

There is a silver lining in this dark cloud of added difficulty though. As Squyres noted last month and reiterated this month, the mission is focused on morphology and not the chemistry and mineralogy of rocks which has been the focus for the rover for 13 years. “We’ll be looking at the landforms, the topography, the details of the sediments, and what one might be able to see in microscopic images. This work doesn’t really have a significant geochemical or mineralogical component to it.”

Meanwhile, Bellutta has been working with the MER Power Lead Jennifer Herman, the other rover planners and ops engineers, and, of course, the scientists to plot the rover’s path into the valley, which extends down from the crest into the crater at a slope of about 15 to 17 degrees for a distance of about two football fields or about 219.45 meters or 240 yards. It appears that the plans for Opportunity to rove into the valley after solar conjunction have changed.

Even before June ended, Bellutta had calculated the first of three planned drives back toward and – yes, at last – into Perseverance Valley. “I’ve located a couple of potential spots inside the spillway about 10 meters east of the lip,” he said June 29th.

During the long July 4th holiday weekend, if everything goes as planned, the rover will embark on the first of three drives that will take her to one of those spots, which, being east of the rim crest or valley lip means inside Perseverance Valley. There, on a gentle slope the Mars explorer can park and wait out the two-week communications blackout of solar conjunction. “We’re aiming for a nice cozy spot with about 10 degrees northerly tilt,” Bellutta said. That’s 5 degrees better than what Herman recommended for solar conjunction.

Then, during conjunction, the rover, operating on ‘auto-pilot,’ can check out other choice north-facing slopes for winter. Although winter solstice in the southern hemisphere of Mars where Opportunity is exploring isn’t until November 15th, the deep freeze of the season will set in two to three months before then, and the more time the rover and her human colleagues have to check out the north-facing slope possibilities, the better.

As the MER book closed on June 2017, Squyres paused to reflect on the intensity of the last few weeks. “It just feels magical,” he said. “We have been incredibly fortunate and now we have this marvelous opportunity and deep obligation to do everything we can with the vehicle, and we’re just going to keep going as long as we can. Perseverance Valley is one of the most exciting features of the whole mission and it’s right there for the taking,” he said. “And we’ll be driving in real soon.”

Deep Dive into June

After wrapping up her 14th merry month of May with a drive to the third waypoint on her walkabout atop Perseverance Valley, Opportunity, with 44,855.67 meters (44.85 kilometers / 27.87 miles) on her odometer, woke up to another hazy day at Endeavour Crater.

The dust from the Martian spring storms still dulled the sky and the MER team recorded an atmospheric opacity or Tau of 0.834. The accumulated Martian powder on the rover’s solar arrays was blocking almost half of the sunlight streaming down to the ‘bot. Despite the solar array dust factor of just 0.543, however, Opportunity was still managing to produce 376 watt-hours of energy, plenty enough to complete her assignments.

The robot field geologist got right to work on Sol 4747 (June 1, 2017) shooting image after image with her Pancam and Navcam to capture the view all around her. Then, she spent a couple of sols taking care of routine tasks and a couple of other overdue chores. She snapped some close-up pictures of the Rock Abrasion Tool’s (RAT’s) grind bit with her front Hazard Cameras (Hazcams) and later pointed her Microscopic Imager (MI) up to collects sky flats, giving her Instrument Deployment Device (IDD) or robotic arm a bit of a workout in the process.

“RAT bit imaging did occur on Sol 4748,” confirmed Project Engineer Stephen Indyk, of Honeybee Robotics, the company that built the RATs for Spirit and Opportunity. Steve Ford, a mechanical design engineer at Honeybee and the RAT’s Payload Downlink Lead (PDL) for the bit analysis, reported that the RAT bit imaging sequence executed successfully.

According to Ford’s report: “All motor commands ran to completion, and the Hazcam images look good and have provided the data required to evaluate the bit wear,” said Indyk. “In performing analysis on the images, a simple pixel correlation to distance is utilized. In other words, by measuring the base and pads of the RAT bits in pixels, the known base width is used to determine the width of the grind pads. To get a handle on error, a root sum of squares method is used.”

The pixel counts remain the same as those from the last bit imaging on Sol 4420 (June 30, 2016). “So the difference in bit wear from the last grind operation remains unchanged,” said Indyk.

Once all her tasks were finished, the MER team commanded Opportunity on Sol 4750 (June 4, 2017) to make a short, tight backward arc to turn, something she’d done countless times before. “We toed out the left front wheel and saw the current on the steering actuator spike up,” said Nelson. “The encoder counts went to zero and the drive stopped. Although the steering actuator on that wheel stalled before any driving could take place, just steering the wheels resulted in 0.02 of a meter (2 centimeters or about 7/8 inch) of motion,” he elaborated. In the world of MER, every centimeter counts and is documented.

Each of the Opportunity’s six wheels has its own drive motor, “which is connected to the transmission so to speak,” said Nelson. Those, of course, turn the wheels, and all six drive motors are working well after more 44 kilometers (or 27 miles) of roving and climbing. Each of the four corner wheels also has an independent steering actuator that includes a motor and gearbox. Those control the azimuth or horizontal, back-and-forth direction of the wheels.

While the rover jammed her right front steering wheel back on Sol 433, April 12, 2005, it was only stuck inward about 8 and she has driven more than 40 kilometers (about 25 miles) like that. But when the left front steering actuator jamming the wheel in a toed-out position of 33 degrees in June, it was, well – a little harrowing.

The MER engineering ops team pondered the problem. “One theory was that that the wheels had caught on something and the cleats or the webbing had dug in making it so the rover couldn’t turn, and the actuator stalled out,” said Nelson. So, on Sol 4752 (June 6, 2017), Opportunity followed commands to test that theory.

First, the robot arced back again, this time without steering the left-front wheel, and then she imaged the location of the steering stall. With that maneuver, the ‘bot’s rear wheels were straightened, but the left front wheel hadn’t budged.

The small patch was promptly dubbed Laramie after one of the train stations along the first transcontinental railroad between New York and San Francisco, the naming theme for target at the top of Perseverance Valley. A splotch of white crumbles was uncovered in the mushed up mix and at first it seemed to suggest a terrain effect, possibly indicating that the rover might have uncovered some outcrop underneath the top surface.

The next step would be to carefully attempt to straighten the left-front wheel in another maneuver planned for Sol 4754 (June 8, 2017). In the meantime, members of the MER ops engineering team joined former MER ops engineers in a tiger team to determine the best next step to unjam the wheel and to try and figure out what caused the stall, and the science team focused on the intriguing white crumbles in the mix Opportunity just churned up.

The robot used the Pancam to take a closer, 13-filter look at the white spot she’d just uncovered. “We saw a drop in reflectance in the 1009 nanometer Pancam band and we also saw a drop in reflectance in the 934 nanometer Pancam band,” said Bill Farrand, Senior Research Scientist at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado and a member of the MER science team. “So it does look different than what would expect and potentially indicates a broader absorption feature than some other lighter-toned targets, like the gypsum veins, which only had a drop in the 1009 nanometer band.”

In other words, given past research and findings, Laramie hinted of past aqueous activity. But with Earth-Mars solar conjunction coming up in July and the mission’s eighth Martian winter setting in not long after that, along with the stuck left front wheel and the need to get into Perseverance Valley soon, the team decided against checking out Laramie with the MI and the APXS; therefore, there is no way of saying for sure what exactly Laramie is or isn’t. However, said Farrand: “I do think it’s plausible that it could be some kind of hydrated sulfate mineral based on the Pancam spectra and the fact that we have seen these spectra in other appearances of sulfate minerals, like at Pinnacle Island and Stuart Island we saw farther north on the rim.”

On Sol 4754 (June 8, 2017), Opportunity followed her new commands and tried to straighten her left-front wheel by steering it inward. “Our tiger team suggested that we try to do that using four different voltages to see at which voltage the wheel straightened,” said Nelson, a member of that team. But it didn’t work. The wheel failed to steer and there was no change in the encoder counts at any of those voltages. “Every one faulted similarly. The current went up to its limit of about 2 amps and there was no significant motion,” he said.

At this point, the tiger team was pretty much convinced that this meant it was not terrain interaction. So on Sol 4756 (June 10, 2017), they commanded Opportunity to do a test on her left rear steering wheel, “just to gather engineering data and to confirm correct sequencing of the Sol 4754 straightening test on the stalled left-front actuator,” said Nelson.

The left-rear wheel performed nominally with the wheel steering as expected, thus verifying their test procedure. “That test succeeded at every voltage and gave us a nominal signature in the current, proving that we had done everything correctly and that the stall which happened on the left front wheel was truly some sort of bad stall, perhaps a mechanical issue with the steering actuator,” Nelson said.

“There was a great deal of consternation within the engineering team that this might be it, that we’d be stuck driving with the left wheel rotated outward 33 degrees,” said Arvidson.

“The mood was a bit pessimistic,” added Fraeman. “But we were still optimistic that we could drive the rover. It would just be more of a challenge.”

The MER ops tiger team – which included Callas and Nelson, Fred Calef, Heather Justice, Ashley Stroupe, and former MERsters Jeff Biesiadecki, Randy Lindemann, Mark Maimone, Joe Melko, and John Waters – continued their investigation. In addition to developing further diagnostics for Opportunity, they also planned ground testing with the Surface System Test Bed (SSTB) rover, a functional engineering model of the MERs.

While the robot’s mobility status was under evaluation and with a summer shortage of Rover Planners (RPs), the robot field geologist spent the next week working in place. She pointed her Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS) skyward to take an atmospheric argon measurement for a mission long study of Mars’ atmosphere on the evening of Sol 4757 (June 11, 2017). But the robot spent most of her time shooting targeted 13-filter images of high-value targets and frames for an extensive panorama with her Pancam.

The intensity of the unknowns surrounding Opportunity’s stuck left front wheel caused some stress and put some pressure on the MER team. But this team has handled so many impossible situations in the past 13-and-a-half years and giving up wasn’t even in consideration.

As the rover worked on collecting images from her parked position, waiting for her human colleagues to send up the next wheel commands, the scientists and engineers fueled their hope with humor. The mission’s next big mural, they decided, would be called the Sprained Ankle Panorama.

On Sol 4763 (June 17, 2017), the team decided to have Opportunity try and straighten that left front wheel again. The team’s irrepressible optimism paid off and it seemed clear that the mission’s lucky star really is still shining after all these years.

This time, Opportunity was commanded to straighten her left front wheel using increasing voltage steps from 15 to 24 volts. “We typically see motion at 15 volts although the standard is to apply 24 volts,” said Nelson. “The reason for using the different voltages was to try to determine how solid any obstruction was and where in the actuator it was located. An obstruction near the motor would take full motor torque or the highest voltage to overcome while one in the gear train could possibly be cleared with less motor torque, lower voltage, because part of the gear train multiplied the torque."

The first six motions stalled, but then, on the very last straightening attempt, the actuator appeared to break free from whatever was impeding it and steered the wheel to straight. “Everyone was completely floored,” said Fraeman.

No other movement was detected and Opportunity’s odometry remained at 44,857.00 meters (44.85 kilometers / 27.87 miles), said Nelson. “We saw a current spike up to about 2 amps for a couple of counts and then it dropped down significantly and the wheel turned back to effectively zero,” said Nelson. With that, the left front wheel was straight again and all the rover’s wheels – except for the stuck right front wheel – were straight.

It was something of another miracle on this miracle mission to Mars. The MER team heaved a collective sigh of relief. But this little unexpected event was also a timely reminder. “It was clearly a reminder that this is an aging vehicle,” said Squyres. “Opportunity has given us a really good reminder that we’ve got to stay focused and get as much as can out of this vehicle while it’s still functioning. We need to stay focused.”

“We believe that there may have been a FOD – which stands for foreign object debris – in the gears and that by wiggling the wheel back and forth or by attempting to straighten it we might have crushed it, smushed it or dislodged it or done something that allowed the wheel to move,” said Nelson.

Nevertheless, this “very good result” was tempered by the fact that the actuator currents were still a little on the high side, Nelson said. “So we’re not sure that cleared the problem, and we still do not know for certain what caused the stall and whether the problem could reoccur.”

“It is possible that the jam could be intermittent,” said Callas, adding that they “are considering further diagnostics on both the left-front and right-front steering actuators.”

With the left front wheel was back to straight, the team decided not to tempt fate and a precautionary partial moratorium on using the steering actuators of both the right and left front wheels was instituted “for the foreseeable future,” as Callas announced.

Since the rover’s rear wheels are also capable of steering, the team engineers decided Opportunity would use only her rear wheels to steer when circumstances demanded, until further notice. No big deal. Not for this rover. She has driven backwards a lot for many years to alleviate the currents on her toed-in right front wheel from getting higher than desired. Having to rely only on her rear wheels to steer, on the other hand, could get tricky going forward depending on the terrain, but she can do this.

Given the team’s ability to use the Hazcams to look both forward and behind, it’s not as complicated as it might seem to the average, non-mechanical Earthling. It does mean the driving will be different now and the rover drivers will have to get used to it.

“We can drive the rover like a car and we can drive it like a tank,” said Squyres. “Your car doesn’t have steering actuators on both ends. It’s only got actuators on one end. Yet you can still parallel park and do all that kind of stuff. So we can drive it that way, using the steering actuators that we have on the back end. We can also drive and turn like a tank.”

Also known as skid steering, tank turning is executed by leaving all the wheels straight and driving one side forward and the other side backward to torque the rover, more or less, around its centerpoint.

So that is the plan for moving Opportunity forward. “We still have a lot of flexibility on how we operate the vehicle and we have a lot of mobility capability,” said Squyres. “I’m not particularly worried about being able to drive this thing.”

With her new driving orders, the rover roved onward toward station 4 on her walkabout atop Perseverance Valley on Sol 4766 (June 20, 2017). Station 4 is not an exact spot so much as a destination area along the southern edge of the large channel or trough that runs east to west, toward the lip of the valley.

Opportunity almost made it, but then suddenly, unexpectedly, she was once again stopped in her tracks. This time it had nothing to do with the left front steering actuator or any of the actuators for that matter. Turned out, the visual odometry (VO) did not converge, probably because it ‘saw’ the Pancam Mast Assembly (PMA) shadow and maybe other rover shadows, which didn't move relative to the rover, suggested Nelson. “This fooled the software into thinking that Opportunity wasn't moving and so it stopped driving,” he said.

This is a safety feature actually, because if the rover is driving, but not getting anywhere, then it would mean it's stuck and the drive should be stopped before she digs herself in deeper. So the drive stopped as it should have; it’s just that the VO was mistaken.

At the end of the sol, the rover succeeded in putting 14.13 meters (about 46.35 feet) of the planned 18 meters, in the rear view mirror, bringing her total odometry up to 44,871.13 meters (44.87 kilometers or 27.88 miles). All things considered, Opportunity is still the ultimate trooper rover and still willing to keep on keepin’ on. “Unfortunately we have limited telemetry that reports how the front struts are coping with the added stress of tank turns, but so far so good,” said Bellutta. What this all means is that so far on good terrain, the driving capability is not too bad. Rocky or sandy terrain might be a different thing.” Time will tell.

Even though the driving was good, the team faced yet another challenge as Opportunity tried to drive north from station 3 to station 4. “As we drive to the north, given the fall season, the difficulty is that the times in which the vehicle is awake and has the energy to drive, we’re looking directly into the Sun,” said Arvidson. “So we’re getting a lot of glare on the Hazcams and Pancam images as we shoot to the north.

On Sol 4767 (June 21, 2017), the team adjusted and Opportunity headed a little more “westerly” to try and ensure that the drive images would not be totally washed out as a result of driving into the late afternoon Sun,” said Nelson. Using tank steering only – which does not require the use of the steering actuators but rather differentially runs the wheels on either side of the rover – the robot drove 14.04 meters (46.06 feet) and closed in on the chosen area the scientists had chosen at station 4, Then, as usual, she took the usual end of drive images that, thankfully, are less washed out.

After spending Sol 4768 (June 22, 2017) taking images because of due a lack of RP support, Opportunity drove another 10.07 meters (33.03 feet) on Sol 4769 (June 23, 2017), employing "tank steering," just like the previous drive. She stopped on the edge of the channel or trough at station 4. There, the robot took images with her Navcam and Pancam, documenting the southern wall of Perseverance Valley.

“The southern and northern walls are minor walls, but there is still some relief and still some rocks outcropping,” said Arvidson. “We’re looking to see what’s on the walls, what kind of rocks are there and have they been transported or are they weathered dikes – or whatever.”

On Sol 4772 (June 26, 2017) Opportunity drove 8.1 meters to the center of the channel, “where we look back at the wall on the southern margin of the valley and image that wall and the floor of this putative channel,” said Arvidson. This time, she used her rear steering actuators to perform a gentle arc and finished the drive with a turn-in-place that toes-in both rear wheels.

The following sol, the rover drove inside the large channel or trough and put another 12.15 meters (39.86 feet) in the rear view mirror, stopping at a position just in front of the north wall, not quite to station 5. That same sol, Opportunity worked with the MER engineers trying to see if she could straighten her right front wheel, the wheel that has been stuck inward about 8 degrees since Sol 433 (April 12, 2005) when it jammed during an end-of-drive turn after a long 151-meter (495-foot) drive southward from Voyager Crater.

“Who knows? After dragging and pushing the stuck right front wheel over rocks and sand, uphill and down, maybe whatever jammed the steering in 2005 has finally been dislodged,” said Nelson. “So we're going to try some small wheel wiggles just to see if anything has changed. If the wheel could be straightened, of course, it would be easier to drive, and more accurately, too, without the constant unpredictable yaw from an angled wheel."

“Why not?” agreed Squyres. “The right front steering actuator has not gone through a whole lot of an insanely large number of turns, however it still has gone through 4700 thermal cycles – hot-cold, hot-cold, hot-cold – thousands of times. And all of the actuators and everything on the vehicle have been through that,” he said. “We could lose other parts of at any time. But this rover has surprised us so many times, I don’t what it’s capable of at this point.”

When all was said and wiggled, “[t]he wheel seems to have moved about 0.1 degree, but we are still confirming this,” said Bellutta. The team will try it again in coming sols.

Opportunity drove up to station 5 on Sol 4774 (June 28, 2017), the final stop on her walkabout. There, at the northern wall of the possible channel, the robot field geologist took the routine end of drive images with her Navcam and Pancam. She continued her next imaging assignment and ended up shooting out of June. “We want to image the north wall of this shallow depression for a nice mosaic,” said Fraeman.

The skies had cleared a little bit more through the month, with Tau recorded at 0.744. The rover, with a dust factor of 0.528, however was producing just 324 watt-hours of power. The plan was to have Opportunity park on a spot “tilted slightly to the north to catch some sunshine,” Arvidson said. “I have recommended a northward tilt of ~5 degrees before conjunction,” said Herman.

On June 29th on Earth, MER rover planners sent Opportunity the first of two 3-sol plans for the long holiday weekend. Since robots don’t get vacations, as a rule, the rover will spend the first part of the long American Independence Day holiday imaging and taking care of routine business through the first couple of sols in July.

Then the next day, the end of June, Bellutta and Ashley Stroupe sent another 3-sol plan that will enable most of the humans to take a break over the holiday as well as schedule Opportunity’s next drive. “Up until Wednesday [June 28th], we believed we had no RP for Friday [June 30th], but we did the impossible and found replacements on Curiosity, so that Ashley and I could work today on ol’ Oppy,” said Bellutta. “We really do care about our vehicles, so MER and MSL do cooperate to maximize science return from Mars.”

Although there is some friendly rivalry between teams, they also cover for each other when family issues come up or someone needs a vacation day. “We always come together when "sand hits solar deck,” as Bellutta put it with a chuckle.

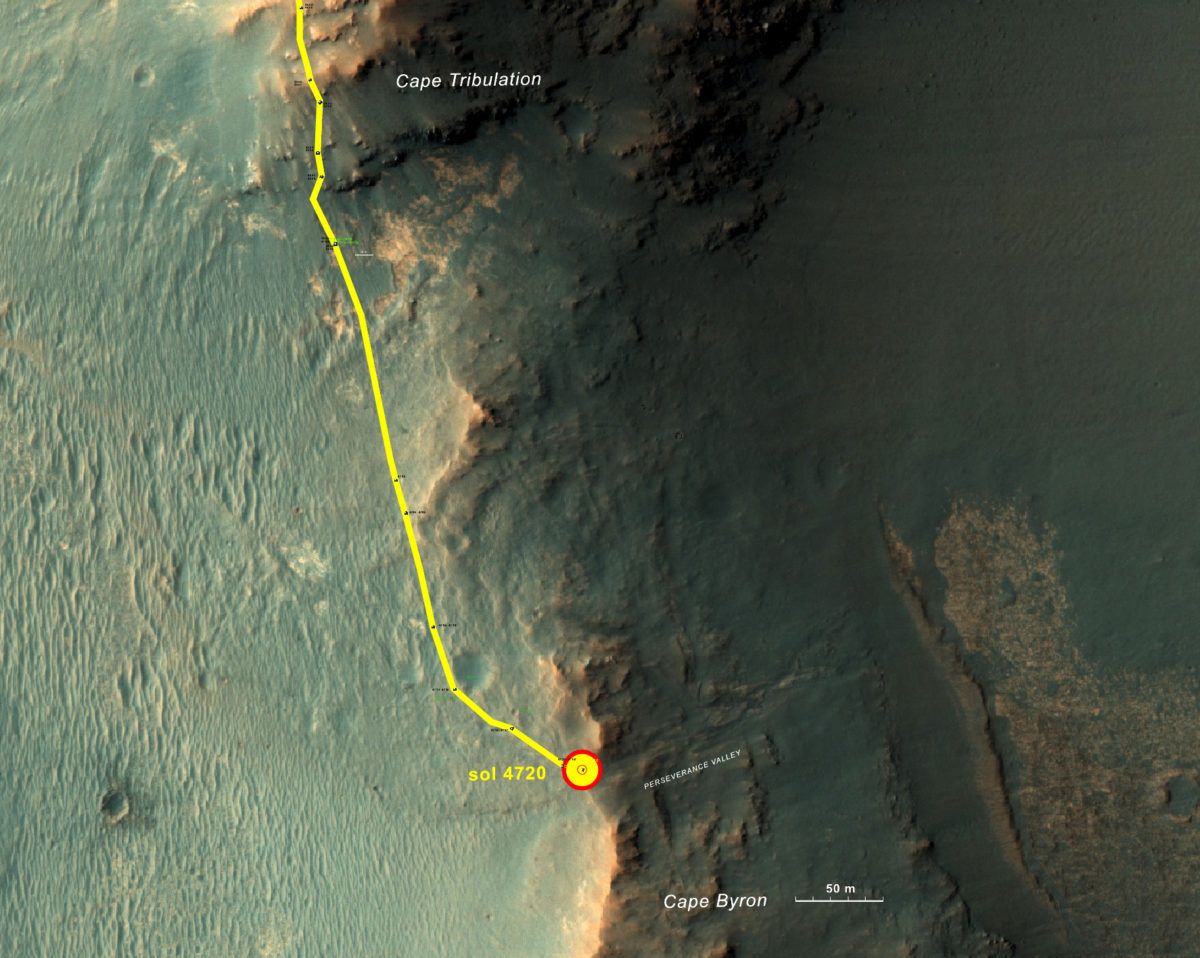

So Opportunity, according to the last set of 3-sol commands, will drive next on Sol 4779 (July 3, 2017), just a week before her 14th launch anniversary. With a little luck, she’ll wind up close to the spot where she first pulled into the top of Perseverance on Sol 4720 (May 4, 2017) or, said Bellutta, a bit southwest of Sol 4720, near the crest of Endeavour’s rim or the lip of Perseverance in advance of solar conjunction. We are heading to the valley,” he said. “It will take probably three drives to get there.”

Once the July 4th holiday is over, the rover will only have a week or so to get in place for the Earth-Mars solar conjunction and so the team soon will be choosing on which “nice cozy spot with about 10 degrees northerly tilt” the robot field geologist will wait out the two-week communication blackout. Having zeroed in on a couple of potential spots about 10 meters east of the lip of the valley, the plan as of presstime appears to be that Opportunity will drive over the lip and enter Perseverance for conjunction.

“The idea is to drive as close to the lip on Sol 4779, then depending on the viewshed, how far we can see, we will be driving into the valley in what has been referred to as ‘spillway,’ then take a couple of drives to park,” said Bellutta. “In the ‘spillway,’ there's a small hump that divides the spillway and generates a small area that features some slopes with northerly tilts of about 10-degrees. That is the current state of events,” he said just before June turned to July.

Because there will be only a few weeks between the end of solar conjunction and the time when Opportunity really needs to be on a nice north-facing slope soaking up as much sunshine as possible in preparation for the mission’s eighth Martian winter, the team wants the rover “to be as close as possible to good, north-facing locations” for conjunction, added Bellutta.

Although the winter solstice in the southern hemisphere of Mars occurs on November 15th, the Sun will begin to rise and set lower in the horizon and the freeze of the season will set in two to three months before that. “Once we resume operations we should be able to continue our science observations, potentially hopping between ‘lily pads,’” said Bellutta. “We call locations of good northerly tilt ‘lily pads,’ because our telemetry display application shows these spots using that color, he added.

This team is ready, as always. Herman has estimated the solar array energy available each sol through the Martian winter solstice, based on assumptions for the amount of atmospheric and accumulated solar array dust and many different iterations of rover tilt. From those results, “I recommended a northward tilt of ~5 degrees for Opportunity during solar conjunction and ~10 degrees of northward tilt during winter,” she said.

Her recommendations went to Bellutta, who considered them along with images from the Mars orbiters to determine all of the local terrain that would meet the tilt recommendations. “Paolo and the other rover planners are working now with the science team to determine the drive targets for conjunction and for winter,” said Hermann.

The MER team has operated Opportunity on Mars now for more than 50 times longer than the originally planned mission duration of three months. It’s an almost indescribable achievement especially considering that back in 2003, almost no one outside the team believed Spirit and Opportunity would each land safely and complete their 90-day primary missions. “We're doing exactly what we should be doing, which is to wear out the rover doing productive work – to utilize every capability of the vehicle in the exploration of Mars,” said Callas.

The new drive restrictions will make it more difficult for Opportunity to use the IDD in terms of precision placement on targets, and driving into Perseverance Valley may well present unknown trials and tribulations. But, all her ailments and limitations aside, this rover is imbued with all the willingness, determination, and capability of her human colleagues on Earth and if she proved anything this past June, it’s that she still has the right robot stuff.

“The thing that’s so great about Perseverance Valley is that it’s a completely new problem,” said Squyres. “It’s a completely unprecedented opportunity. It’s nothing that anyone’s ever seen down on the Martian surface. It’s a historic first. The rover is healthy and well suited for the problem at hand. It’s incredibly exciting and I can’t wait to drive in there,” he said. “I think it’s going to be another wonderful adventure.”

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth