A.J.S. Rayl • Dec 31, 2016

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Wraps 2016, Heads into 2017 Toward 13th Anniversary

As 2016 came to an end and 2017 rang in, Opportunity was working the first leg of the ascent up the rugged western rim of Endeavour Crater on her way to an ancient gully, the next scientific tour de force down the road, and the Mars Exploration Rovers (MER) mission was closing in on its 13th anniversary of surface operations coming up in the New Year.

The veteran robot field geologist has been making her way across and up the rocky slopes of the crater rim at Cape Tribulation since leaving Spirit Mound in November. The objective is to get to the other side of the rim and onto the flatter terrain of the Meridiani Plains that surround Endeavour’s rim. From there, the rover can cruise south to Cape Byron and enter the gully from the top, right where the MER scientists want to begin their research.

Facing steep, slippery slopes and boulder fields, Opportunity navigated through some of the most challenging terrain she has ever attempted in December, demonstrating her right robot stuff every rove of the way. “Getting up the rim is difficult stuff,” said MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres, of Cornell University. “This is the toughest sustained climb Opportunity's ever done in nearly 13 years on Mars.”

The MER scientists believe that the gully, which is the centerpiece of Opportunity’s tenth mission extension science campaign, was carved by water during the Noachian Period some 3.7 to 4 billion years ago. This is the epoch when many planetary scientists believe Mars was more like Earth, with lakes, rivers, and perhaps even an ocean. Research at this site will mark the first time any surface mission has studied an ancient Martian gully this old up close. Whatever the rover finds, it will make history. But the first order of business is getting up and over the rim.

“We're driving to the southwest, going up hill, moving as fast as we can and not doing much else other than imaging,” said MER Deputy Principal Investigator, Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis. “We pretty much have blinders on to get up the rim and out onto the Meridiani Plains to boogey on south.”

As Opportunity clawed her way uphill, the year wound down. Using her Panoramic Camera (Pancam) and Navigation Camera (Navcam), the rover dutifully documented her surroundings along the way. Of course these images open the window on Mars for all Earthlings, but at the same time they function as science tools, the visuals on which the team now relies to confirm the rover’s locations and to chart the course ahead.

Gully or bust

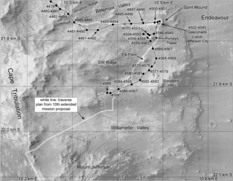

This map shows a portion of Endeavour Crater's western rim that includes Marathon Valley, which Opportunity explored in 2015-2016, and a fluid-carved gully at Cape Byron that is the tour de forceattraction for 2017. The width of the area covered is about 800 meters (about a half-mile). North is up. JPL’s Tim Parker, a MER science team member, who originated the Mars Ocean hypothesis, mapped the rover's traverse with a gold line onto an image from the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). Zoom in to see route.NASA / JPL-Caltech / University of Arizona

The going was tough, sometimes painfully slow, but the tough little rover kept going, putting 15, 20, or 30 meters at a time in the rear view mirror. “The rover has entered really rugged terrain and she's often near the limits of what she can do, yet she soldiers on,” said Chief of MER Engineering Bill Nelson, of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), home to all NASA’s Mars rovers. of JPL.

Most of Opportunity’s drives in December took the rover up in elevation, but she had to juggle a number of challenges, as she will until she reaches the rim top. “The slopes are steep, anywhere from 15 to 25 degrees, and in some places the terrain has not been as firm as we might like and the rover has slid on loose rock and regolith,” said MER Project Scientist Matt Golombek, of JPL.

Then there’s the issue of power. While Opportunity’s energy levels are good enough to meet her drive and science objectives, the rover’s solar power production should be higher this time of year. “There are two issues,” said Arvidson. “The tilt of the rover as it climbs is away from the Sun makes for reduced solar radiation for the solar panels, and so we don't have as much energy as we'd like. The other issue is the crater’s rim to the west of where we are. It masks part of the sky, which is bad for power and bad for communication with Odyssey, which impacts our ability to downlink data.”

And there are the rover’s own handicaps, the “physiological” hits Opportunity has taken and adapted to since landing in 2004. Just after waking up on Mars for the first time, the robot suffered a stuck "on" heater that forces her to shut down every night. And over the years and across the miles, her right front steering actuator "froze," locking up that wheel, and her shoulder joint broke, forcing her to drive with it partially deployed. In recent years, Opportunity lost her long-term or Flash memory.

No big deals though, at least for the rover. “Aside from all that" said Nelson, “Opportunity has been performing much the same as when we took her out of the box.”

True to her MER mettle, Opportunity pressed ever onward in December, skillfully avoiding the dangers as she scaled terrain much too treacherous for her bigger, more scientifically sophisticated cousin, Curiosity, to even consider.

With the summer Sun shining on Endeavour, although not always on the rover’s solar arrays, Opportunity managed to make it through Bitterroot Valley and to the edges of Willamette Valley, “the next valley on the upward trend to get out of the crater,” as Arvidson put it. There, the mission checked off another good year, although, as Golombek noted, this mission has “never really had a bad year.”

In any case, MER’s lucky star did seem to be shining as the robot explorer glided through her seventh Martian winter and escaped the potential wrath of the spring dust storms. Through it all, she delivered the work of exploration, sending home reams of research about past water and ancient environments around Endeavour, not to mention current data on the atmosphere and the state of the planet today. “We’re making good, steady progress,” Squyres said at month’s end.

“2016 is yet another successful year for the rover,” summed up MER Project Manager John Callas from JPL. “Opportunity completed the Marathon Valley science campaign and began the next phase of her exploration plan. The rover's health continues to be excellent with no [recent] change in performance, remarkable when you think what this 90-day rover has been through.”

From a science perspective, it just keeps getting better. The rover’s new phase marks a significant new beginning. After more than a decade of being more or less a rock mission, 2016 signaled the beginning of “a fundamental transition,” as Squyres called it, to a new phase of research into geomorphic features that hint of ancient liquid water that pooled or flowed or trickled in these parts a long, long time ago.

When the ball dropped in New York City and 2016 gave way to 2017, Opportunity was less than a kilometer (about a half-mile) from the top of the gully. However, the next 200 meters (about 656.16 feet) will be arduous, grueling uphill hiking that will challenge the rover and the team in unforeseen ways.

The MER mission is a science driven mission, but it’s gully or bust now and the team is bent on getting the rover to that next big attraction as soon as possible.

“We're at this point now where we know we have this fantastically important target out ahead of us,” said Squyres. “The seasons are changing and we know this uphill driving puts stress on the vehicle and none of us are getting any younger on Earth or on Mars. It would take something really extraordinary to get us to stop for any extended period of time at this point. Right now, it's all about getting up the hill and to the top of the gully.

And so as 2017 takes hold, Opportunity’s prime directive will remain the same: climb, drive, ascend.

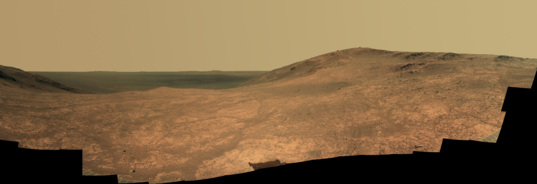

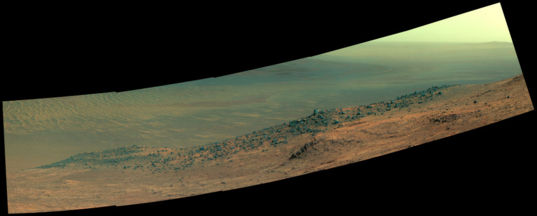

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / Arizona State University

Marathon Valley

Opportunity used her Panoramic Camera (Pancam) to take dozens of images in April and May 2016 that went into this panorama of Marathon Valley, which the MER team named the Sacagawea Pan. The view is to the northeast toward the floor of Endeavour Crater. The high point in the right half of image is Knudsen Ridge, part of the south wall of the valley. Kelsie Crawford, a Pancam calibration analyst and undergrad in Astrophysics and Physics at Arizona State University, merged the exposures taken through three of the Pancam's color filters, centered on wavelengths of 753 nanometers (near-infrared), 535 nanometers (green) and 432 nanometers (violet) and created a near final mosaic for Planetary Society President and Pancam science lead Jim Bell to “polish.” This is approximately true color.Flashback 2016

When 2016 rang in at Endeavour Crater, Opportunity was at the eastern end of the south wall of Marathon Valley defying the brutal cold of her seventh Martian winter. The Winter Solstice in the southern hemisphere of the Red Planet arrived January 3, 2016 GMT (about the same day that Spirit bounced to a landing in Gusev Crater 12 years before). But the robot was in good shape in January, soaking up the winter Sun from the north-facing slopes in her winter haven.

The rover climbed onto one of those north-facing slopes just a month or so before, and her energy “jumped by 40 watt-hours, from the 340's to 381 watt-hours,” reported Jennifer Herman, MER's power team lead. That's more than one-third the power producing capability the rover had on landing with clean solar arrays, and better than the original winter projections. Energized, Opportunity by all indications would not have a problem roving and working through the winter.

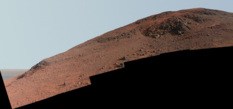

Knudsen Ridge

NASA-JPL released the above panoramic image of Knudsen Ridge on Feb. 25, 2016. Opportunity took dozens of images that went into this image in October 2015 and finished ‘filling in holes’ in February 2016. The Pancam team processed it in enhanced color. Reddish rock within and between the knobs near the top of the scene is what the rover team calls a "red zone.” The many red zones in Marathon Valley correspond to locations of clay minerals mapped from orbit.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

The robot was on the hunt for the mother lode of clay minerals that the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM), an instrument onboard Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), first detected back in 2009. To that end, Opportunity was conducting a kind of “electric slide” across Knudsen Ridge, which caps the south wall’s eastern side.

Clay minerals – hydrous aluminum phyllosilicates known to feature iron and magnesium, in geology-speak – are a big deal on Mars for two reasons: they form in the presence of water; and they have been linked to the emergence of life on Earth and the theory of abiogenesis. In 2012–13, Opportunity and the MER mission made history on Matijevic Hill at Cape York, becoming the first surface mission to groundtruth the presence of clay minerals on Mars. And, they found those clay minerals, specifically smectites, in the oldest Martian terrain or strata ever found by a ground-based mission, known now as Matijevic Formation.

The quest since then has been to uncover more examples of these landmark clays and ancient bedrock and whatever other remnants from the Noachian Period that might still be there. Opportunity had been scouting for the clay minerals since driving into the valley, an area roughly the size of three football fields, in July 2015. But Mars presented the mission with a mystery in Marathon Valley: although the orbital instrument showed the smectites to be everywhere, they were nowhere in sight.

The scientists however quickly zeroed in on red bands that appeared in the images Opportunity sent home. They swirled all around Marathon Valley, running in between and around outcrops on the valley floor and along the slopes of its walls. These bands or “red zones,” as the team dubbed them, seem to speak of past water that must have once trickled or flowed through these parts a long, long time ago.

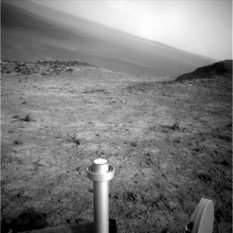

Pvt. Whitehouse

Opportunity took this raw image with her Navigation Camera on Sol 4311 (Mar. 10, 2016), the Martian day she made her last attempt to get to the first of four Pvt. Joseph Whitehouse targets atop Knudsen Ridge. Whitehouse-1 is the bright outcrop patch just above the bright cylinder on the Instrument Deployment Device (IDD).NASA / JPL-Caltech

The robot had already examined red zone rocks on the floor of the valley. “Cruddy” and “crumbly,” they turned out to be “a jumble of accumulated stuff,” as Squyres described them. The bedrock atop Knudsen Ridge offered the scientists in place bedrock, something the rover could sink her instruments into, if, that is, she could climb to the top of the ridge and get close enough to study it.

In the meantime, Opportunity took dozens of images for the Knudsen Panorama and used her diamond-toothed Rock Abrasion Tool (RAT) to twice scrape and grind into a tan-red bedrock target named Private John Potts, enabling the scientists to establish a baseline for the most ubiquitous rocks in the valley. And then, the robot checked out a soil patch, named Private John Collins, and then searched for possible altered rock inside red zones on the ridge.

The team had chosen the naming theme for targets in 2015, even before Opportunity entered Marathon Valley. They decided to recognize and honor the explorers on the Corps of Discovery Expedition, led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, during their 1804-‘06 trek across much of what is now the western United States. And so the naming theme continued as the MER mission began a new year.

After celebrating her 12th anniversary on her Sol 4267 (January 24th 2016), Opportunity inched slowing up the steep slope of the ridge trying to reach Private Joseph Whitehouse, waiting at the top. On her final drive of the month, the rover was at a tilt of 30.6 degrees. “That’s a tilt higher than any we’ve seen in more than 4000 sols, since we had to stop a drive back in Endurance Crater when we hit a tilt of slightly over 31,” said Rover Planner Ashley Stroupe, of JPL. “We are right at the limit of what we have driven or climbed as far as slopes,” Nelson added.

The rover spent February in a mostly stationary position on the slope, “the steepest slope Opportunity has been on since Karatepe on Endurance Crater,” said Squyres. From that perch, she took additional images for the Knudsen Ridge Panorama with her Pancam and studied a rock named after Charles Caugee, one of the boatmen hired by Lewis & Clark.

Got it!

Opportunity captured this rare image of a Martian dust devil twisting through Marathon Valley with her Navcam on the final sol of March 2016. Note the rover's tracks. They lead up a north-facing slope that forms part of the southern wall at the western end of the valley, near where the robot spent April 2016 sleuthing smectites.NASA / JPL-Caltech

About 20 centimeters (7.87 inches) in the long dimension, Caugee is “a rock-size rock that's sitting on downslope” from Pvt. Whitehouse, said Golombek. The immediate theory was that it fell from the in place bedrock at the ridgetop, which posited Squyres, “may be a kind of broad alteration zone.”

Meanwhile on Earth, the MER officials worked on the proposal for their tenth mission extension, a routine requirement for every already extended planetary mission. The grant would fund the mission and keep Opportunity on the road through 2018.

In March, Opportunity pushed the limits of her human-given capability on the steep slope, despite the rubble-laden terrain. The robot’s resolve had everyone following her adventures and her ops team marveling as she inched her way toward Pvt. Whitehouse. These rovers, however, weren’t designed to be mountain climbers. Despite her human-infused determination, even Opportunity has limits.

“This target was important enough to do anything we could do to get there,” said Stroupe, whose been driving for the mission since 2005. Opportunity got to within inches but was unable to reach the bedrock and inspect it up close with the Microscopic Imager (MI) and Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS). “We gave it our best shot,” Nelson said.

“The slope was steeper than any either Spirit or Opportunity ever climbed,” said Arvidson. In fact, Opportunity's tilt reached 32 degrees. Considering that the rover’s tilt limit is 30 degrees, she exceeded expectations and no one was blaming the ‘bot.

Field of smectites

Geologist-volcanologist Larry Crumpler plotted Opportunity’s April 2016 walkabout on this image, a rover view into the interior of Marathon Valley acquired back in early 2015. The rover scientifically scrutinized the area, which appeared to be a field of clay minerals in orbital data. Crumpler is Research Curator for Volcanology & Space Science at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science and a MER science team member.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / NMMNH / L. Crumpler

By mid-March, the rover was backing down Knudsen’s steep slope and driving up the floor of Marathon Valley to a more accessible red zone destination at the other end of the valley’s south wall. And at month’s end, the rover was on a gentle slope near the head of the valley where it cuts into the western rim of Endeavour’s 22-meter (13.7-mile) span, surrounded by “beautiful bedrock swept clean of sand with a very strong smectite signature,” as Arvidson described it.

On the final sol of March, Mars delivered something special, perhaps for all of Opportunity’s effort at Knudsen Ridge. A dust devil whirled through the interior of Endeavour Crater and right before the rover’s eyes. A common sight for Spirit when she roved through Gusev Crater, dust devils have been devilishly uncommon for Opportunity. But on this particular sol, she captured it in an image.

Opportunity dedicated the first half of April to a walkabout around her new site and later took the images needed for a detailed panorama of the entire area. The CRISM data indicated this was an ancient field of clay minerals that left a lot of residue behind.

From the images the rover sent home, the MER scientists chose an outcrop on the southwestern part of the walkabout that they named Pierre Pinault, and then spent the rest of the month examining a target there. The rover even deployed her Rock Abrasion Tool (RAT), brushing the spot and grinding into it to look at the inner surface up close with her MI and glean its chemical composition with her APXS.

On Earth, the scientists’ analysis was revealing that Pinault is an impact breccia, typical of what the MER team is seeing in Marathon Valley. “But it’s in the red pixel area, where CRISM detects a strong smectite signature,” reminded Arvidson. And that seemed to indicate that the smectites are part of the terrain. “They have to be,” he said. “Most likely the smectites are carried by the flat polygonal breccias, because the red stones we have seen are so small, they couldn’t possibly be what’s carrying the signature.”

“The key here is that thing is Mars keeps giving us new stuff to do,” said Squyres.

Scuffed bounty

These images – shown here in false color and in 3D – show the mysterious "jelly doughnut" rock, Pinnacle Island (in lower left corner) and the location where the MER team is now convinced it had been before suddenly appearing in January in a place it had not been just days before. Opportunity took this image on her Sol 3567 (Feb. 4, 2014) with the panoramic camera (Pancam), after backing away from Pinnacle Island. Just uphill (up and to the right in the image) is Stuart Island, which has a similar dark-red center and white edge. This is the area, where the rocks and tracks are, that Pinnacle Island was before the rover drove over it in early January and "tiddly-winked" it to its current location. The rover's solar panels had blocked this view while it was studying Pinnacle Island. The stereo version, second image, appears in 3D when viewed through red-blue glasses (red lens on the left). For scale, Pinnacle Island is about 1 meter (3 feet) from Stuart Island.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / W. Farrand, SSI

With the Martian winter on the run, Opportunity’s future was looking brighter by the sol. The robot field geologist spent the first half of May finishing her study of Pinault, taking dozens of panoramic images of Marathon Valley, and empowering herself with the first faint signs of spring.

A Martian spring however is no breeze though. The dust storms the season generates can spell death for solar-powered robots, pummeling them with the red, powdery stuff that can blanket her arrays. At the same time the winds stir up gusts that can whisk layers of accumulated dust from the rover’s arrays, giving her a newfound lease on life.

Turned out, Opportunity “enjoyed storm-free skies,” according to the MARCI Weather Reports, throughout the merry month of May.

After wrapping work on Pinault, the rover drove through a red zone at her new site and scuffed it up. There, beneath the top layers, was a small bounty of geological gems, a colorful trove of sands and pebbles. “Mars has totally surprised us, again,” said Arvidson.

Bill Farrand, Senior Research Scientist at the Space Science Institute, and member of the MER science team, worked with the Pancam multispectral images the rover took and helped the team determine which pebbles inside the trenched area Opportunity should look at up close. As May was winding down, the rover homed in on a yellowish pebble the team named after Joseph Field, considered to be among the best shots and hunters accompanying Lewis and Clark on the Corps of Discovery Expedition.

The yellow pebble was a best shot too, featuring “one of the highest sulfur contents seen anywhere on Mars,” said Squyres. “It validates the notion that these [red bands or zones] are indeed places where there has been significant aqueous alteration, but I don't think there is one of us who expected this.”

On May 24th, Squyres and Callas presented their tenth extension plan. “Twelve and a half years after landing,” summed up Callas, “we still have a great rover and a great mission.”

Opportunity carried on and Mars smiled down, keeping the dust storms at bay as the rover drove into her 150th month of surface exploration in June and began checking off the last of the science investigations in Marathon Valley.

NASA-JPL issued the MER mission’s panorama of Marathon Valley on June 14th. It is a sweeping view looking eastward into Endeavour, and the team named it in honor of Sacagawea, the Shoshone guide and translator who helped Lewis and Clark successfully trek across what is now the western portion of the United States.

Opportunity worked away, checking out another pebble in the scuff, this a red one named for George Drouillard, a civilian interpreter, scout, hunter, and cartographer on the Corps of Discovery Expedition. Then the rover drove to the center of the site that the team dubbed the Red Square because the CRISM map indicated it was “hot” with the signature of smectites. There, she checked out one more outcrop, focusing on one called York. Once that was complete, the rover headed back onto the valley floor.

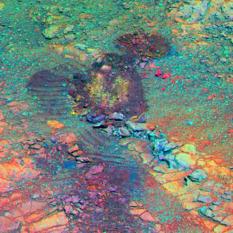

Sleepy_II

Opportunity roved upon this intriguing suite of “purple” rocks nestled together on the floor of Marathon Valley toward the end of July 2016, as she was on her way to shoot a new segment of the valley’s north wall. The MER scientists concluded the rocks, which contain more silicon and aluminum and look purplish in the false color Pancam versions, fell off from the valley’s northern wall.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

“We pretty much have the smectite story here, but we wanted to make sure we got into middle of red pixel area in case anybody asked,” said Arvidson.

While the scientists hoped for a repeat of Matijevic Hill in Marathon Valley, they didn’t find any of the ancient bedrock that predates Endeavour Crater and underlies the crater’s Shoemaker Formation impact breccias. Instead, they were finding something different. “There is water and ice and mechanical transport and some degree of chemical alteration,” said Arvidson. “But it’s not balmy Cuba we’re talking about here. It’s more like Greenland.”

At the end of the Martian day or sol, the mission’s seventh Martian winter left the team with little to complain about. “It went pretty well, and we're in the process of wrapping up and beginning our next adventure on Mars,” summed up Callas.

Life on Mars was good. So was the word on Earth. On July 1st, NASA announced that it was granting the MER mission its two-year extension. Just three sols later, the Spring Equinox shined down on Opportunity who was hunkered down, once again, over the outcrop called York recapturing images that had been lost in transmission. And three sols after that, the team quietly remembered the 13th anniversary of Opportunity’s launch from Cape Canaveral.

The MER mission also paid tribute to Viking in July, 40 years after that mission put two spacecraft into orbit and two landers, the first ever to safely land, on the Martian surface. By all accounts, Viking is the “giant on whose shoulders” all Mars missions stand, and especially those that dare to land.

In honor of Viking’s 40th anniversary, the team changed the naming theme for Opportunity’s final science campaign in Marathon Valley, nicknaming rocks and other features after targets the two Viking landers checked out. They were names Arvidson knew well. He was the team leader of the Viking Lander Imaging Team from 1977-1982.

Opportunity rolled and rocked on through the month examining a purple rock named Bashful_II, which the scientists found to be slightly higher silicon and aluminum, “pretty much” like Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, the first purple rock (and then a new rock type), which the mission inspected on a ridge north of Marathon Valley back in February 2015.

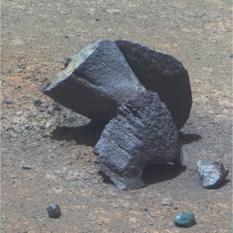

Groovin’ on a Sunday afternoon

Opportunity took this image with her Pancam in August 2016 as she was investigating deep cut grooves, emerging into frame from the right. The Pancam team processed the raw image into this false color version, so the scientists could better see and analyze the geology and geomorphology.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

By July 21st, the robot was maneuvering through an open path in the boulder field below Hinner’s Point. It was “an obstacle course,” Seibert said, and a tricky drive since the rover was on a 15-degree slope. But the rover and her drivers persevered and just a couple of sols later logged another drive record as Opportunity passed the 43-kilometer mark, pushing her odometer to 43.046 kilometers (26.747 miles).

As the rover motored on to the most eastern segment of the valley’s north wall she will visit, she happened upon an intriguing suite of purple rocks nestled together on the valley floor, which the team dubbed Sleepy_II. And which the robot just had to check out.

By the end of July, Opportunity was completing another month of work under “storm free skies” and the rover’s power levels were consistently above 600 watt-hours more than half her full capability with clean solar arrays after landing in 2004. Meanwhile, the MER scientists had generally settled on “a good, detailed, sensible, publishable understanding of what we found in Marathon Valley,” as Squyres put it then.

The science team concluded that the red bands that define the red zones are ancient fractures that effectively created pathways the water followed, and are more significantly altered by water than the outcrops. “The red zones are surface expressions of places where the preexisting fracture system allowed water to come to the surface and produce localized alteration, and it's been pretty pervasive,” said Squyres. “Actually, that's the reason there's no bedrock in the red zones, the stuff there is just completely weak and crumbly as a result of being altered.”

While the scientists did not find evidence for an ancient lake or sea or river in Marathon Valley, they did find plenty of evidence that water once did flow through it. “The rocks that show the smectite signatures, whether from orbit or from the ground, all suggest mild alteration by water, except when you get into the fractures,” Arvidson clarified.

The low water-to-rock ratio findings do not threaten the theory that Mars was once more like Earth, with lakes, rivers, and perhaps even an ocean, though they may somewhat alter the picture of Mars’ ancient, more Earth-like environments.

In any case, their findings are “consistent” with what they saw at Matijevic Hill, Arvidson noted. Interestingly, they are also consistent with what Curiosity has found at Gale Crater, where there are ancient river, lake, and delta deposits. “There was a lot of water at Gale, but not a lot of aqueous alteration except in the fractures,” he said.

When all was inspected, imaged, and done, what Opportunity found in Marathon Valley may not have been explosive, the data add to the story of water on Mars, as well as the past environments in which the smectites, iron magnesium clay minerals, formed. The take-home science, said Arvidson, “is telling us more about the overall history of Mars and action within the fractures.”

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / Arizona State University

Wharton Ridge Panorama

In early October 2016, NASA-JPL issued Oppy’s latest panorama, which the MER team named in honor of Robert A. Wharton (1951-2012). Heralded as an astrobiologist before the field officially came into existence, Wharton was a pioneer in the use of terrestrial analog environments, particularly in Antarctica, to study scientific problems related to the habitability of Mars. During his career, he also worked as a visiting senior scientist at NASA Headquarters. The full extent of Wharton Ridge is visible, with the floor of Endeavour beyond it, and the far wall of the crater in the distant background. Near the right edge of the scene is the Lewis and Clark Gap, through which the rover crossed from Marathon Valley into Bitterroot Valley in September 2016. The Pancam team processed the image in enhanced or false color.When August knocked on the mission’s door, Opportunity’s work in Marathon Valley was all but done. “We have a few more things we need to knock off, but we're on our way out of Marathon Valley right now,” Squyres said then. “Of course, there's always the what-if-something-surprising pops up,” he added.

And, as the mission’s fate would have it, as the rover departed Sleepy_II for the eastern most segment of the valley’s north wall to complete a color mosaic of Gibraltar_II, something surprising popped up. The rover had stopped mid-drive to focus her Pancam on Big Joe_II, a “knob” structure, and in those mid-drive images the scientists saw winding grooves that resembled the deep red zones, except they were carved much deeper into the terrain.

The initial plan was for Opportunity to be roving to the Lewis and Clark Gap, her exit from the Valley, located just to the east of Knudsen Ridge, by Sol 4474, (Wednesday August 24, 2016). But the grooves got to them. These features just may foreshadow what the rover will find down the crater rim road. “If in fact the gully is a real carved channel, it may be these smaller features are in some way related to them and are telling us something about the fluvial history that existed in the erosion of the rim of this crater,” explained Golombek.

So, once the work on the color mosaic at Gibraltar_II was downlinked and in MER’s digital can on Earth, Opportunity headed back to the sinuous features. The robot took a stereo image of the area and took a close look at the deeply carved features. When she wasn’t shooting grooves, the robot was conducting an in-depth examination of a small rock in the area that the team named Muffler_II, with the MI and APXS.

A 3D image of the grooves and a map of the topography of the area will provide data for the scientists to compare with features the rover is likely to find later on the way to and at the gully in Cape Byron. The rover worked quickly and efficiently.

As August was beginning to shutter, the work in “grooveland” was completed, and Opportunity, at long last it seemed, took off for the Lewis and Clark Gap. Despite feeling the de-energizing side effects of the Martian spring for the first time in the season, the visibility and the rover’s power were already improving as the rover pulled up to her exit.

“The rover continues to be very healthy and productive,” said Callas then. “We're in good shape and we're poised to begin our extended mission.”

When September began,Opportunity was at the gap preparing for departure. The robot spent the first sols of the month taking pictures of the valley just to the south, which the team would soon name Bitterroot Valley, and what she could see of the route her colleagues on Earth had charted. The rover’s new adventure was about to begin.

On analyzing the images Opportunity had taken from the ground, the rover planners confirmed the route they charted was safe, at least this part of it. She was good to go.

The three primary science objectives for the robot during the tenth mission extension are to search for more Matijevic Formation rocks; study the gully in Cape Byron in detail; and examine the Burns Formation breccia rocks inside Endeavour Crater. And in between, of course, check out any of those Martian mystery things that pop up.

Opportunity was slated to try and achieve the first objective as soon as she departed Marathon Valley and arrived at the mission’s first science stop. Before she drove through the gap though, the robot field geologist focused her Pancam on a distinctive rocky ridge to the east, on the other side of the Lewis and Clark Gap from Knudsen Ridge, completing one last assignment. The images would go into the mission’s next big panorama that would be named in honor of pioneer astrobiologist Robert A. Wharton (1951-2012).

Then on September 4th, after more than a year of exploring Marathon Valley, Opportunity drove through the Lewis and Clark Gap ahead of schedule and “blasted downhill,” as Squyres described it, into Bitterroot Valley and toward the interior of Endeavour Crater. The next adventure in the first overland expedition of Mars had begun.

Although the drive took Opportunity down challenging, 15-degree slopes peppered with rocks and cobbles, for the rover drivers it was “fantastic” and “better driving than we were expecting,” said Seibert. “We're driving on tough terrains, and the rover is handling it very well,” Stroupe added.

As Opportunity was approaching the first science stop, a distinctive mound, the team changed the naming theme to places that the Corps of Discovery visited during the 1804-‘06 expedition. Spirit Mound was on the list. It struck a chord for the obvious reason. “Many of us thought it was appropriate that we name the first stop after something significant,” said Stroupe. For Squyres, it was “a no brainer.”

Once she arrived at Spirit Mound, the rover immediately began checking out a standout, light-toned linear outcrop named Gasconade, and then chalked up another record, completing her 4500th hundred Martian day or sol of exploration. That “exceeds the prime-mission duration by a factor of 50," Callas wrote in an email of acknowledgment to the MER team. It was another September to remember.

For its part, Mars continued to smile down on the little golf cart-sized ‘bot. Despite two nearby regional squalls that were darkening the Martian atmosphere, once again Opportunity dodged a dust bullet and no major dust storms or fallout showed up at Endeavour.

Parked right up against the western edge of Spirit Mound and hunkered down over Gasconade, the rover worked into October, studying the rich yet familiar geology of the outcrop. The MER mission did pause however in the middle of the month to take a shot at freeze-framing part of the descent of the Schiaparelli lander dispatched by the European Space Agency (ESA).

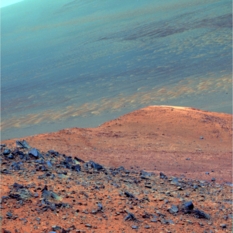

Spirit Mound from Pompys Tower

Opportunity took this image of Spirit Mound with her Pancam in November 2016 from a perch on the rocky slopes of Pompys Tower, the second mound the robot checked out in 2016. Named for Pompeys Pillar in Montana, a site Lewis and Clark visited, the team chose the original Clark spelling, said MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres. This view shows part of Pompys (left), Spirit Mound, and the rippled floor of Endeavour Crater in the distance. The Pancam team processed it in false color.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

The rover had less than a 1 in 3 chance of capturing images of Schiaparelli’s parachute, arguably about the same odds the little lander had of safely landing. Moreover, even if both lander and Opportunity succeeded, the parachute would only show up as one pixel in the rover’s Pancam frames. But the MER team was okay with standing down from the mission’s work for a few sols to support of ESA’s little lander.

But on October 19th, just 50 seconds before Schiaparelli was to land, its mission control lost contact. Turned out, the little lander crash-landed and Opportunity didn’t catch the glimpse of the parachute on the way down. It was a harsh reminder that landing safely on Mars isn’t easy.

On Spirit Mound, Opportunity didn’t uncover any Matijevic Formation bedrock that the scientists had hoped to find. “We got to Spirit Mound and found the same Shoemaker breccias that we've been seeing over most of the rim of Endeavour,” said Golombek. They’re not giving up though, Arvidson said, noting that there is still a chance for uncovering more of the ancient Martian ground later in the extended mission.

Meanwhile, James Shirley, a planetary scientist at JPL, who has been studying the historical pattern of dust storms on Mars, published a prediction on October 5th that Mars was due to experience a planet-circling dust storm in the next few months. But “the Godzilla dust storm” didn’t turn up in October, and as All Hallow’s Eve sent ghosts and goblins into the streets on Earth, Opportunity roved on “still same old good story,” said Callas.

When the Sun rose on November at Endeavour, the robot field geologist was finishing up her work at Spirit Mound. Before the end of the first week though, she was heading across slope to Pompys Tower, the second of three mounds on the rover’s imaging itinerary in Bitterroot Valley.

Opportunity had just begun a trek that would challenge her as never before. After documenting Pompys Tower in pictures and skirting a potentially dangerous boulder field, the rover drove on, across Bitterroot Valley and upslope toward the third mound, which the team named Elk Point.

Summer Solstice came and went on the rover’s Sol 4568 (November 28, 2016) and still Mars was cooperating, smiling down on the rover that loves to rove. Not one storm had darkened Endeavour’s doorstep, yet.

One could sense among the team members however that there was a real push to get Opportunity to the gully, and Squyres acknowledged it. “Until we get to the top of the gully,” he said, “it's all about getting to the gully,”

But getting back up the rim wasn’t going to be easy. In fact, it was going to be a lot of work for the rover and the first leg of this lower section of Cape Tribulation was promising to be "pretty gnarly," Squyres said. “We just blasted down this hill, but getting back up is a real, serious challenge.”

Opportunity drove into December on Sol 4570, hiking 25.28 meters (about 82.94 feet) southwest and up another steep slope, slowly gaining a little more elevation. She took the usual pre and- post-drive Pancam and Navcam images. Although the rover was slated to have spent much of the first week of the month taking more Pancam and Navcam images, she never received the commands because of a problem with a Deep Space Network (DSN) antenna.

Instead, Opportunity executed an on-board run-out sol and then dropped into auto mode, a safe state, and waited for her colleagues on Earth. Once restored to master sequence control, the rover got back to work on Sol 4575 (December 6, 2016), taking those images of her surroundings.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

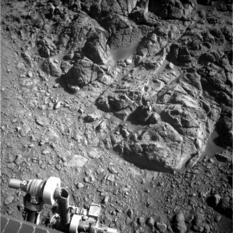

Gasconade

As Opportunity pulled up to Spirit Mound in September 2016, the intriguing, light-toned linear outcrop, pictured above, stood out. After naming it Gasconade, for the river where the Lewis & Clark Expedition set up camp in 1804, the MER scientists directed their ‘bot to check it out. “It's small and very rough,” said MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres. “We'll do what we can with this thing and then it will be time to move on.” Despite its allure and good looks, Gasconade was not the Matijevic Formation bedrock the scientists had hoped to find, but more of the breccias, the Shoemaker Formation outcrop the rover has encountered throughout her years of exploration.Opportunity roved again on Sol 4577 (December 8, 2016), again to the southwest and up slope. The robot was supposed to put 18-meters in the rear view mirror, but only achieved a little more than 12.39 meters (about 40.65 feet). The visual odometry (VO) the rover was using to monitor her progress had failed however, to sufficiently resolve surface features and stopped the drive after 12.39 meters. This is not uncommon when the local terrain around the rover has shadows that confuse the algorithm.

On Sol 4580 (December 11, 2016), Opportunity made more progress to the southwest and upslope, driving 15.5 meters (about 50.85 feet). And then two sols later, she climbed upslope another 17.02 meters (about 55.84 feet). As usual, the robot took the routine Navcam and Pancam images after the before and after the drives. So far, so good.

Since she was hiking up slopes that happen to be tilted away from the Sun though, the rover’s power was constrained. In fact, some sols following the drives were designated 'recharge' sols, during which the rover does little else. Nevertheless, Opportunity was making use of about 67% of the sunlight hitting her solar arrays in mid-December, and producing an acceptable 411 watt-hours under hazy skies.

“The drives have been pretty short because it's difficult terrain and because of the impact the rim has in masking the sky and accessible daylight and communications,” said Arvidson.

It didn’t stop Opportunity. However slowly, the rover trudged onward, putting rugged real estate in her rear view mirror four times during the third week of December. On Sol 4584 (December 16, 2016) she logged 26.26 meters (about 92.71 feet); then another 31.32 meters (about 102.75 feet) on Sol 4586; 21.08 meters (about 69.16 feet) on Sol 4588; and 7.06 meters (about 23.16 feet) on Sol 4589 (December 21, 2016), which took her to a rock the team nicknamed Beacon.

Just before Christmas Eve, the rover bumped 0.73 meters (about 2.39 feet) on Sol 4591 (December 23, 2016) to check out the rock and other nearby targets as the winter holidays consumed Earthlings. It would turn out to be the rover’s last move for 2016.

The final bump of 2016 brought Opportunity’s total odometry to 43,733.77 meters – that’s 43.73 kilometers or about 27.17 miles. Or, viewed another way, it’s 43,133.77 meters beyond the mission success objective of 600 meters, achieved in 2004.

Still, other stuff, out of the rover’s control, out of her team’s control, happens. On December 26th, Opportunity’s primary communication-relay, the Mars Odyssey orbiter, which has been in service at Mars since October 2001, unexpectedly put itself into safe mode. As a result, the rover wasn’t able to downlink her work for four Martian days, from Sols 4594–4597 (December 26-29, 2016). And, since Opportunity is working in persistent RAM mode, she cannot save data overnight. So those sols were “lost,” Nelson confirmed. So at month’s end, the rover got something of an unanticipated summer break.

The Odyssey ops team quickly diagnosed the cause: the orbiter had been uncertain about its orientation with regard to Earth and the Sun. The Odyssey team restored the spacecraft to full operations and Opportunity was back to working and downlinking just before 2016 faded to black.

Oppy’s recent roves

This graphic charts Opportunity's recent rovings, from Sol 4479 (Aug. 30, 2016), about fives sols or Martian days before the rover exited Marathon Valley and headed for Spirit Mound, to a recent drive on Sol 4589 (Dec. 21, 2016), which took the rover to the northeast side of Pompys Tower. The annotated map is courtesy Phil Stooke, an associate professor at the University of Western Ontario, Canada, author of The International Atlas of Mars Exploration Vol. 2, Spirit to Curiosity: 2004 to 2014(Cambridge University Press, 2016). The base image was taken by the HiRISE camera onboard MRO.NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / P. Stooke

Despite a somewhat frustrating end to the year, Opportunity and the MER team wrapped up 2016 and put a bow on it, just like they have every year. “We finished a very successful campaign in Marathon Valley that conclusively demonstrated pervasive aqueous alteration of the Shoemaker Formation impact breccias, especially within fracture zones where enhanced fluid flow was highly likely,” summed up Arvidson.

And the mission was roving on with Opportunity into a new geomorphic phase of exploration. But there’s not much time to stop and reflect when you’ve got a rover to tend every sol.

“I'm always thinking about the next thing and the next big thing is the gully,” said Squyres. “Old gullies have been telling us about ancient processes on Mars from orbit, and have been interpreted since the 1970s and the days of Mariner 9 and Viking. Now we have a chance to actually see one on the ground for the first time. I never even imagined seeing an ancient gully, because there were none of these features even near our landing sites. But we have driven so far out of Opportunity’s ellipse right now that these possibilities are opening up to us. And now it is –,” he said, drifting off into the future. “We just gotta get there.”

Then, 2017 dawned on Mars.

While many millions of Earthlings embark on new resolutions, Opportunity will be taking off on the next leg of her climb up the slopes of Cape Tribulation, slated to begin on her Sol 4602 (January 2, 2017).

The robot still has a rugged 200 meters (about 656.16 feet) to put behind her in order to get to the top of Endeavour’s western rim, but she is driven by her own human-infused DNA and is in safe hands, supported by the most experienced Mars rover driving team in the world. “While we do encounter things we can’t see in the HiRISE images or can’t tell exactly what they are, we’re pretty good at figuring out a way around or through,” said Seibert.

As Opportunity rolls along, the mission scientists and engineers, though having formed a well-oiled ops machine, continue to learn and advance their knowledge about exploring Mars and about their rover. “We do go right up to the limit in lots of places, because there is interesting science to be accomplished from doing that,” said Golombek. “But we have learned what the rover can and can't do.”

Knowing Opportunity’s limits and her human-like determination, understanding the steepness and composition of the terrain, and being able to better “read” the world of Mars in orbital images have given the MER team an edge. And it’s an edge they honor. The team members will never put the beloved rover in jeopardy.

From the mission’s first sol on the Red Planet and especially since Spirit and Opportunity completed their 90-day primary missions, the team members have been roving Mars according to a code and it seems to have emboldened them all along the way. As Squyres first put it so many years ago: “Every day on Mars is a gift.”

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

Spirit on Husband Hill

This special effects (fx) image of Spirit on the flank of Husband Hill, named for Rick Husband, commander of Space Shuttle Columbia's final, tragic mission, was produced using JPL's "Virtual Presence in Space" technology. The size of the rover in the image is approximately correct and was based on the size of the rover tracks in the mosaic.Spirit Remains Silent at Troy

Stuck in the sandy edge of a shallow hidden crater along one side of Home Plate, Spirit phoned home on Sol 2210 (March 22, 2010) just before she went into a planned hibernation.

The robot that came to known as the-little-rover-that-could had worked for more than six Earth years and drove 7,730.50 meters (4.80 miles) in some of the harshest Martian terrain the mission will ever encounter. She was the first rover to climb a mountain, the first robot to take pictures of dust devils on the surface of Mars, and the first to find evidence for near-neutral water on Mars. In those 6+ years, Spirit literally defined MER mettle.

For the next year, NASA-JPL radiated more than 1,300 commands to Spirit as part of the recovery effort to elicit a response, any response. Hearing nothing in all that time, NASA officially concluded recovery efforts on May 25, 2011. The remaining, pre-sequenced ultra-high frequency (UHF) relay passes scheduled with the Odyssey orbiter completed June 8, 2011. No one has heard from Spirit since.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth