A.J.S. Rayl • Sep 05, 2016

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Gets in the Groove, Wraps Science Marathon Valley

Sols 4452 - 4481

Opportunity got in the groove at Endeavour Crater in August finishing the last of her science assignments in Marathon Valley, the Mars Exploration Rovers (MER) team prepared for departure, keen and so ready to drive into its tenth mission extension, and all was right with the world on the Red Planet.

“We have a few more things we need to knock off, but we're on our way out of Marathon Valley right now,” said Steve Squyres, MER principal investigator, of Cornell University, at month’s end. “Of course, there's always the what-if-something-surprising pops up,” he added.

Of course. That’s because MER is science driven. Opportunity was to finish taking the dozens of frames needed for an extensive color mosaic of Gibraltar_II, the most eastern segment of the Marathon Valley’s north wall the mission will visit, then tie up a few loose science ends, and rover on. But as the veteran robot field geologist was nearing completion of her work at the north wall, one of those what-if’s popped up.

“We've had this desire for a while now to not dawdle any longer in Marathon Valley, because of the exciting things that appear to be ahead of us, and so we kept trying to get on with it,” said Matt Golombek, MER project scientist, of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), home to all NASA’s Mars rovers. “And then we found these interesting things and it delayed us.”

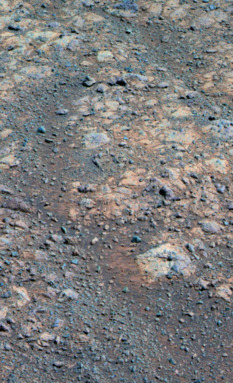

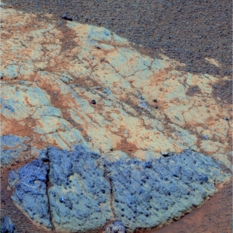

On the way to the Gibraltar_II north wall segment, Opportunity cruised through and around some features captured in images she took during her drive. The next morning on Earth, the MER scientists were struck by features they saw meandering through the terrain. They resemble the “red zones” that the rover studied throughout the Martian winter, which revealed evidence that a little water once ran through these parts.

But the features in these images are deeper, more carved into the terrain. “They’re grooves,” said Ray Arvidson, MER deputy principal investigator, of Washington University St. Louis. At first blush, they certainly look like they might have been carved by water.

Eager as the team was to leave Marathon Valley, the grooves were just too enticing for the scientists to pass up. “The question that arose was: what scoured these grooves out?” said Squyres. “The ones that point downhill are the ones that are scoured, and of course, water tends to flow downhill. Some of them have a sinuous appearance to them, which particularly characterizes things that have been eroded by water.”

Groovin’ on a Sunday afternoon

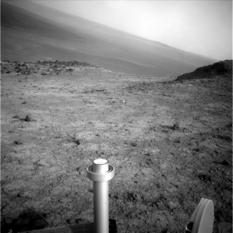

Opportunity took this image with her Panoramic Camera on Sol 4464 (Aug. 14, 2016) as she was investigating grooves seen emerging into frame from the right. The Pancam team processed the raw image into this false color version, a technique that enables the scientists to better discern various geological elements in the picture.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

"We also know that the wind blows up and out on the valley,” added Arvidson. “But we're talking about erosion over periods of billions to millions of years so trying to figure out wind direction historically in that region would be farther than I would be willing to go,” said Squyres. And, a bigger picture question arose too. Could the grooves be related in some way to features seen in orbital images of the gully further south along Endeavour’s western rim, in Cape Byron, a prime destination on the extended mission? That would be something that would be “very, very difficult to tell at this point,” as both Squyres and Golombek noted. But it was a thought.

In any case, the grooves in Marathon Valley may well foreshadow what the mission will find down the crater rim road. So, once the work on the color mosaic at Gibraltar_II was downlinked and in MER’s digital can on Earth, Opportunity headed back to the carved, sinuous features. Imaging the grooves and mapping the topography of the area would provide if not the precise answer to what produced the grooves, an example to compare with features the team will explore on the way and when the rover gets to Cape Byron.

The rover’s research at the grooves revealed that some of them had small red pebbles, like those in the red zones and in which the scientists found solid evidence of past water. Therefore, it bolstered the scientists’ red zone findings that some water trickled through these parts long, long ago, even if it didn’t open the floodgates, so to speak, in Marathon Valley. "One possible hypothesis – and I stress we have not concluded yet that this is water erosion – but one possible hypothesis is that red zones are pre-existing zones of weakness that tend to be exploited by any erosional process,” said Squyres. "Probably what we're seeing here are deeply eroded red zones.”

As Opportunity pulled out of “grooveland,” the general consensus is that these cuts that snake though in the terrain could have been carved "by wind or by water or both,” as Arvidson summed it up.

As for what they will uncover at Cape Byron, only time and about 2 kilometers of driving will tell. “The gully, hopefully, not only has the groove-like structures, but also the sedimentary deposits,” said Arvidson. “We could see the sedimentary rock at Gale Crater and that's what has really demonstrated that Curiosity has driven on ancient lakebed and river deposits.”

The Martian spring meanwhile blew into force in the southern hemisphere of the planet where Opportunity is roving. The notorious Red Planet winds can spell life or death for solar-powered robots. The winds have caused storms that rained dust down onto the rover’s solar arrays, choking her power production capability, and at other times they have whisked accumulated dust from her arrays, thereby lengthening the robot’s life.

Mars continued to smile down on the veteran rover in August, although during the last week of the month, the rover felt the dirty side effects of spring for the first time this season. “Mars is being a little less cooperative than we’d like, but it’s not being really bad to us yet,” reported Bill Nelson, chief of MER engineering at JPL. “We are, however, starting to see an elevated amount of dust from nearby dust storms.”

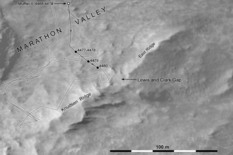

Exit Lewis & Clark Gap

As August began to fade into September, Opportunity was in position to exit Marathon Valley for good. The rover took this raw image with her Navigation Camera on Sol 4480 (Aug. 30, 2016). The robot’s next adventure is just through the Lewis & Clark Gap, top center of image.NASA / JPL-Caltech

The measurement for atmospheric opacity, called a Tau, rose above 1 during the final sols of the month, Nelson said. That’s really hazy, like Beijing on a bad day and the rover’s power dropped by about 150 watt-hours, roughly 1/4th of recent production levels.

Despite losing a little energy, Opportunity continued to work to the end of August “storm free,” according to the Mars Weather Report, prepared by Bruce Cantor and crew at Malin Space Science Systems. And as September was about to peek over the horizon, the visibility was already improving.

This rover has seen worse. In fact, Opportunity survived a planet-encircling event in 2007, so experience and MER mettle is on her side, and the team is as optimistic as it is cautious. “We're getting into the time of year when we see increased dust activity and so we have to keep an eye on the power levels and how much dust in the atmosphere. But we've been through it before and we know how to do it,” said Squyres.

As for Opportunity, the update is “like a broken record,” said John Callas, the MER project manager, of JPL. “But it's a good message: the rover continues to be very healthy and productive,” he summed up. “We're in good shape and we're poised to begin our extended mission.”

The next chapter in the MER expedition begins once Opportunity passes through the Lewis & Clark Gap, located just east of Knudsen Ridge, along Marathon Valley’s south wall.

“Opportunity just keeps chuggin' along,” said Arvidson.

And the team is more than ready to chug along with her. Actually, they’re getting downright anxious. “We’re looking forward to leaving Marathon Valley. We've done just about everything we can here,” Arvidson said.“There are lots of things that lie ahead of us that are very, very exciting,” Golombek added. “I'd say we've gotten a taste of what could be some of those exciting aspects in the last several weeks. So yeah, we're really excited to be getting on with things.”

“Everybody's excited to get on with the next phase,” summed up Squyres. “We're just about finished with what we want to do, and the rover is fine. It’s a healthy vehicle going forward and seems raring to go.”

Squyres, as usual, wouldn’t commit to a specific date for departure. The mission, remember, lives on science time. “It’s time to go when it’s time to go,” he philosophized Yogi Berra style. “It’s the nature of exploration. You don’t do it on a schedule.”

That noted Opportunity’s departure from Marathon Valley is tentatively slated for the first sols in September.

From a rover driver’s point of view, the traverse path that Opportunity is about to take through the Lewis & Clark Gap and beyond is going to be challenging, but, as Mike Seibert, MER lead flight director and rover planner put it: “It’s going to be a lot of fun to drive.”

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / Arizona State University

Knudsen Ridge

Opportunity took the images that went into this color mosaic of Knudsen Ridge over a period of sols or Martian days in October 2015 and finished filling in ‘holes’ in February 2016. The rover will be exiting Marathon Valley in August, through the Lewis & Clark Gap, partially visible at the far left of the image. This image was processed in enhanced color by the Pancam team.When August dawned at Endeavour Crater, Opportunity was in the midst of shooting multiple mosaicked, color, stereo frames of the last segment of Marathon Valley’s north wall the rover visit, for an extensive Panoramic Camera (Pancam) image. Named Gibraltar_II, after a rock in the sample field of Viking Lander 2, the location is east of Hinners Point, toward the crater interior.

On sol 4452 (August 1, 2016), the high terrain wall of the valley prevented the low elevation Odyssey relay pass from receiving and returning any rover data. So Opportunity took care of routine business, like dust monitoring. The ops team commanded the rover to take some more color Panoramic Camera (Pancam) panoramas of Gibraltar_II on the next sol, and then drive.

Opportunity bumped about 6 meters (19.68 feet) closer to an exposed outcrop near the base of the north wall segment on Sol 4453 (August 3, 2016). During the next two sols, the robot took Pancam images of the outcrop from the closer vantage and up the ridge, as well as images of the upper reaches the Gibraltar_II ridge.

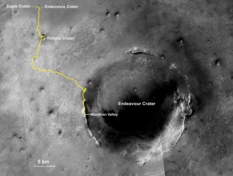

Oppy’s expedition so far

The gold line on this image shows Opportunity's route from the Eagle Crater landing site to her approximate current location. Since August 2011, the MER mission has been exploring the western rim of Endeavour Crater and in July the rover entered Marathon Valley. The base image for the map is a mosaic of images taken by the Context Camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). Larry Crumpler, of the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, provided the route add-on.NASA /JPL-Caltech / MSSS / NMMNHS

“The valley floor has these polygonally fractured light-toned breccias exposed that are carrying the clay mineral signature, but the wall of the valley looks different,” said Arvidson. “The wall rocks look different and appear coarser grained, so we wanted to image the wall to see if we could find the contact [or boundary line] between the valley floor rocks and the wall rocks, but a lot of it is covered by windblown soil.”

The MER scientists are still analyzing the rover’s images. The contact is “not crisply defined,” said Arvidson. “We’re still debating if we see it.”

Following the plan to leave the north side of the valley, Opportunity took some pre-drive imaging of Sleepy _II, and then headed southeast on Sol 4456 (August 6, 2016). During her 31-meter (101.70-foot) drive toward the Lewis and Clark Gap, the exit from Marathon Valley, the rover stopped mid-drive to focus her Pancam on Big Joe_II, a “knob” structure.

In those mid-drive images, the scientists saw intriguing grooves that resemble the deep red zones the rover found all over Marathon Valley, except they are deeper. That, in addition to the way the grooves meandered downhill, seemed to suggest fluvial action, or formation as a result of liquid water. The science team decided the grooves were too groovy to pass up.

With imaging of Gibraltar_II in the digital can on Earth and as the second week of August got underway, Opportunity took a pre-drive picture of an exposed outcrop named Rocky Flats_II that was just to the north of her on Sol 4459 (August 9, 2016). Then the rover drove 13.04 meters (42.78 feet) to the northwest and got in the grooves.

The rover’s prime science directive for the ensuing two weeks was to take detailed images of the features and visually document this “grooveland.” That assignment would include taking both long-baseline and short-baseline stereo imagery with the Pancam, as well as multispectral images of chosen grooves. These datasets will enable the team to create a detailed Digital Elevation Model (DEM) or in layperson’s terms, a 3D representation of the terrain’s surface.

“Long baseline means rather than just using the spatial offset on the rover’s mast between the left and right eyes for Pancam, the rover takes images from one spot and then moves a couple of meters and take more images of the same place,” explained Arvidson. “The larger the baseline separation, the higher the fidelity of the resulting topographic maps generated from the stereo images,” he said. The baseline between the image locations is larger than the separation between the two cameras on the rover’s mast, and it is this separation that allows for the image to appear 3D.

View into Endeavour

Opportunity spent the first week in August taking images of the most eastern segment of Marathon Valley’s north wall that the MER mission will visit. She took this image looking into the interior of Endeavour Crater with her Pancam on Sol 4483 (Aug. 3, 2016) and the Pancam team processed it in false color.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

On the other hand, “a short-baseline reduces distortion of the immediate area,” Nelson pointed out, which, with regard to the one outcrop near the bottom of the northern ridge that was of interest to the scientists.

Not long after her return to “grooveland,” Opportunity bumped 1.8 meters (5.09 feet) to set up for the first station for long-baseline stereo imaging. After several sols of working on that, the rover bumped 5.43 meters (17.81 feet) to the north to set up for the second station for the other half of the long-baseline stereo imaging that will be used to create the DEM.

The grooves are not to be confused with channels. For starters, they are not as deep as channels however they are deeper than the red zones the robot investigated in various places in Marathon Valley during the Martian winter. “It’s a generic term,” said Arvidson. “'Channel' has more of a formation connotation; whereas, a groove is just a groove,” he said.

But what is a groove and how did these grooves get here, in this place in Marathon Valley?

The MER scientists are considering several hypotheses. “One is that these grooves are just fractures eroded by wind,” said Arvidson. “Another is that they have had some water running through them, because they are going downhill and they're fractured and all broken up. And some of these grooves also have some red pebbles in them,” he said. Thus, at this point, the scientists are thinking that the grooves could have been carved by wind or by water or by both.

Opportunity continued to focus on the grooves and closed the second week of August groovin’ on a Sunday afternoon. Then she continued her extensive imaging campaign throughout the third week of the month. As hundreds of people flocked to Graceland on August 16th, the 39th anniversary of the death of Elvis Presley, the rover was rocking in “grooveland.”

In between shooting stereo images of the grooves, Opportunity also worked in a few cloud movies, some measurements of atmospheric argon with her Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS), and took some multi-spectral images of chosen targets with her Pancam. Whenever available downlinks permitted, the rover also returned more data from her errant flash or long-term memory drive.

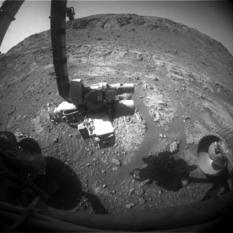

Imaging outcrop at Gibraltar_II

Opportunity took this partial selfie with her Front Hazard Camera as she was imaging an outcrop at the base of the Gibraltar_II segment of Marathon Valley’s north wall. The scientists are still looking to see if they can find the contact or boundary between the bedrock on the valley floor and the rocks on the ridge. The contact, however, “is not crisply defined,” said MER Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis. “We’re still debating if we see it.”NASA / JPL-Caltech

The rover is not currently using her flash; it’s been out of commission for nearly a year. The mission is operating its field geologist in RAM mode, which means Opportunity has to offload each sol’s work the same day before she shuts down for the night, because the data in her Random Access Memory or volatile short-term memory drive will not be saved.

While there is a possibility Opportunity will fire up her flash down the road, according to Callas, neither the rover nor her ground crew seem to be all that concerned anymore. “We do not anticipate using flash again,” said Squyres. “It has degraded over time and we have mastered the operation of the vehicle without flash. All you have to do is look at our recent mosaics and drives and panoramas to see that. And we are certainly prepared to operate in persistent RAM mode for the rest of the mission.”

On Sol 4468 (August 18, 2016), Opportunity bumped 2 meters (6.56 feet) to the north to set up for short-baseline stereo imaging. The robot field geologist also took some Navcam images of the Gibraltar_II segment of the valley’s north wall and checked out a rock of convenience up close.

Although there should have been bedrock in the workplane before her after the bump, instead there was rocky debris. “Unfortunately the rover slipped about 10 centimeters beyond the planned stopping point, and so the workplane was full of mostly small rocks as opposed to the bedrock we expected,” said Nelson.

Nevertheless, on Sol 4470 (August 20, 2016), the science team selected a small rock, which they named Muffler_II, in honor of Midas Muffler, a rock near Viking Lander 2, for close-ups with the Microscopic Imager (MI) and APXS integrations to determine its chemical composition. It would keep the rover busy in timeslots when she wasn’t shooting “grooveland.”

As the fourth week of August took hold, Opportunity was still taking short-baseline stereo images of the grooves. But on Sol 4473 (August 23, 2016), the rover turned her attentions to Muffler_II-2 and off-set her APXS for another integration on the small rock.

The plan had called for Opportunity to be roving on toward the Lewis & Clark Gap on Sol 4474, (Wednesday August 24, 2016), and with the scientists and engineers eager to go, it’s no wonder why they didn’t. Except, the grooves got to them. Even when the rover did head south, she would still have some additional remote sensing to complete, as well as a quick stop to re-image some previous targets before the MER ops team would command her to exit Marathon Valley.

Opportunity carried on. She completed a Pancam mosaic of the grooves on that sol, along with an APXS measurement, and also took some 360-degree images with her Navigation Camera (Navcam). The rover then bumped back just 0.62 of a meter (2.03 feet) on Sol 4475 (August 25, 2016) to get a closer look at some nearby surface targets and to take a 13-filter or multispectral images Pancam of Muffler_II. Not surprisingly, the small rock looked “similar to all the other rocks in Marathon Valley,” said Arvidson.

Red zones and grooves

When the MER scientists caught sight of grooves snaking through images that Opportunity took on her way to finish imaging the Gibraltar_II area (top image), they decided to delay departure from Marathon Valley and have the robot go check them out. “Probably what we're seeing here are deeply eroded red zones,” said MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres, of Cornell. The mission investigated red zones (bottom image) throughout the Martian winter earlier this year, and uncovered evidence for a small amount of past water. The grooves may be evidence of more water.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

The following sol, 4476 (August 26, 2016), Opportunity took some 13-filter or multispectral Pancam images of rocks on the edge of the groove in front of her, and some Pancam color images to the southeast looking toward Lewis & Clark Gap.

While the MER scientists believe the best examples of these grooves and this kind of erosion lie farther south along Endeavour Crater’s western rim, the realization that these grooves might be a similar sort of feature motivated them to document it well. “We thought it was valuable to document what could be – and I stress could be a good example of fluid-carved features, and so we spent a couple of weeks doing a lot of high-resolution Pancam imaging,” said Squyres.

Although it will take some time to put the long-baseline and short-baseline stereo imagery datasets together, from the images Opportunity has returned, it’s clear that the DEM of “grooveland” will offer “pretty high precision out to fairly substantial distances away from the vehicle,” said Squyres.

The robot’s research on the grooves will likely serve the MER science team well. “This is indeed preparation for the gully stuff,” said Squyres. “We have out ahead of us – at the gully and also another target we're going to drive by on our way – features that seriously look like they have been carved by flowing fluids, water or debris flow or something like that. These will be the first fluid-carved channels that have ever been seen up-close by a rover on Mars. That's where we're headed,” he said.

“But as we were driving out of here and when looked at the geometry of the grooves we were seeing, we noticed that some of the grooves here in Marathon Valley had a sinuous appearance and some had a braided appearance, which can be characteristics of things that are eroded by liquid water,” Squyres continued. “We had to ask ourselves if the erosion here had anything to do with the process that carved the features we’re going to be driving to.”

The only way they would be able to determine that is to document the groove features in Marathon Valley and document them well. By Sol 4477 (August 27, 2016), Opportunity’s work in “grooveland” was deemed done and the rover took off.

“We're leaving these grooves in the rear view mirror, heading across the valley toward the south side,” said Callas. “We will have a chance to visit more grooves and in a more accessible place. For us right now, it’s kind of like window-shopping for a restaurant” he said. “You've looked at the menu and this place looks cool, but you know the restaurant down the street has an even more exciting menu and that's where you're having dinner. So you're eager to get there. What we see ahead of us is just so exciting.”

Opportunity successfully put 49.01 meters (160.79 feet) behind her that sol as she drove southeast across the floor of Marathon Valley toward the Lewis & Clark Gap, making a small dogleg at the end of the drive. The rover stopped at a chosen waypoint, marked station 6 during the mission initial walkabout. On the next sol, she took care of routine business, rested, and recharged.

The robot field geologist continued her trek toward the Lewis & Clark Gap, logging another 15.36 meters (50.39 feet) on her rocker bogie on Sol 4479 (August 29, 2016) to close in on her next destination.

The following sol, 4480 (August 30, 2016), Opportunity took some color images for a Pancam mosaic of a ridge that is just to the east of Knudsen Ridge, on the other side of the Lewis & Clark Gap toward the interior of Endeavour. The freshly imaged ridge is to be officially named soon. Then, Opportunity drove 11.79 meters (38.68 feet) to meet up again with some old “friends.” It was the rover’s last drive of August and it brought her total odometry to 43,180.94 meters (43.18 kilometers, 26.83 miles).

The rover first visited this troop of targets on the southern side of the valley back in October 2015 and November 2015. Each named for a member of the Corps of Discovery, more popularly known as the Lewis & Clark Expedition, the targets are: a dusty, deep red zone target named Private John Shields, "somewhat like the other red zone red rocks, except it's dirty," said Arvidson; a soil target named for Private John B. Thompson; a blue cobble named Private Peter Weiser, and an outcrop target, named Private Ebenezer Tuttle, which Arvidson described then as "representative of rocks and materials on the lower part of the south wall.”

Some of the images the robot took of the privates in 2015 never made it to Earth, so the rover was assigned a “do-over.” The drive put Opportunity right in front of Pvt. Tuttle, with Pvts. Shields, Weiser, and Thompson nearby, ready for the picture party. Not long after her reunion, the robot successfully sent the scientists’ desired multi-spectral Pancam of Pvt. Tuttle to Earth.

Recent roves

This graphic charts Opportunity's recent rovings and science stops, and shows the Lewis & Clark Gap, courtesy Phil Stooke, associate professor, University of Western Ontario, Canada, and author of The International Atlas of Mars Exploration Vol. 2, Spirit to Curiosity: 2004 to 2014(Cambridge University Press, 2016). The base image was taken by the HiRISE camera onboard MRO.NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / P. Stooke

Opportunity spent her last sol in August, 4481 (August 31, 2016), taking another 13-filter or multispectral Pancam image of all the Privates, and followed it up with a measurement of atmospheric argon for the mission-long study on Mars’ atmosphere.

As August came to an end, the MER ops team was keeping vigilant watch on the weather. “We’re hoping things will peak and then go back to normal rather than getting worse,” said Nelson.

So far, so good. Opportunity was producing 453 watt-hours of power. The robot still had a decent solar array dust factor of 0.693, and the Tau had already dropped from 1.2 to 1.079.

Still, any measurement over 1 can’t be ignored. But the hazy skies are not dusty enough to stop this rover, and the MER mission is fueled in part with optimism. “We’re continuing our science planning, moving toward the gap and onto our extended mission,” Nelson said. “From the rover’s viewpoint, we’re doing great.”

Just one and a half Earth years ago, the anticipation for Opportunity’s finishing the world’s first marathon on another planet and then driving into and exploring Marathon Valley was as high as it’s ever been for the MER team, except perhaps for landing. Those moments are likely to remain forever unparalleled for so many people involved in this miracle mission to Mars.

At this juncture, Opportunity and the team are ready already to get back on the road. “I'm tired of Marathon Valley,” Arvidson said, echoing the sentiments of many team members.

Parting Marathon Valley may not seem such sweet sorrow right now, however there are some “bittersweet feelings,” said Callas. “From an engineering perspective, Marathon Valley was what we were expecting,” he said. “We took advantage of the slopes inside the valley, which provided for favorable solar illumination during the winter, and that allowed us to be fully active throughout winter even with the complexities of persistent RAM operation. So Marathon Valley provided us with a safe and comfortable place for the winter. We had an idea there were some juicy science targets, but we didn't really know what we would find here.”

What the science team did find in Marathon Valley wasn’t exactly what they had hoped to find, but it certainly revealed there’s more mystery to Mars to be unraveled. “We went there because of the strong smectite signatures from the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) on MRO and we were all kind of hoping we'd be looking back [in time 3.7 to 4 billion years] into Matijevic Formation, pre-Endeavour-impact rocks that have a clear montmorillonite signature, like we saw at Cape York,” said Golombek. “Instead, we found Shoemaker breccias, slightly altered, probably by groundwater, with some small component of clays, enough to give off the phyllosilicate signatures that CRISM detected. But we did not find any Matijevic, pre-impact rocks.”

Still, Mars ultimately gave up enough secrets for the team to be able to write a well-researched story about Marathon Valley’s past watery environment. “It turned out to be different story from what we thought it might be, yet it's still an interesting and important one,” said Squyres. “More than the smectites, the clay minerals detected by CRISM, the red zones turned out to be the main story at Marathon Valley. They tell of an aqueous process that we really hadn't seen elsewhere before and we were able to document it.”

“It's like so many things in life,” Callas reflected. “You look forward to these great events, but the way you think about them in the future versus the way you reflect on them in the past is so different. Mysterious things are exciting and intriguing, but now that Marathon Valley has become familiar to us, it's lost its mystery. And that's been true with Mars in general.”

Ancient Martian bedrock

About a year after Opportunity drove up to the western rim of Endeavour Crater, she discovered the most ancient Martian strata ever found by a surface mission on Mars. The team named it Matijevic Formation, in honor of Jake Matijevic, a member of the original MER design team and the mission’s chief engineer for a number of years, who passed away in 2012. The robot took this image of the first Matijevic rock she found, dubbed Whitewater Lake, in December 2012. It was in this strata that the rover ground-truthed the first clay minerals on Mars. This image processed in false color by the Pancam team.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

The only way to cure those mystery blues if you’re a rover on Mars is to keep on roving. Once her final science assignment is finished, Opportunity will be doing just that. “We're going to creep up to the Lewis & Clark Gap and takes images to see what it looks like and see whether we can go down there or not,” said Golombek, chuckling.

The rover planners are pretty certain they can guide Opportunity along the planned route. “I expect the route from Lewis & Clark Gap will be traversable,” said Seibert. “But until we image the terrain south of the Gap, we will not know for sure. Right now, our traverse path is based on images from HiRISE on MRO.”

With the resolution of the HiRISE elevation models, some features appear more rounded and thus less difficult to traverse than they will be once imaged from the surface. Even so, the MER rover drivers are the most experienced in the world. And, said Seibert: “We have built up confidence in our analysis based on previous uses of HiRISE digital elevation models for path planning and in then driving those paths.”

As for Opportunity? She continues to amaze everyone. If you consider that way back when, at the end of their first year, the twin MERs were deemed to be centenarians in rover years, then Opportunity is nearing 1300 Earth years of age, though that may be debated or challenged at the end of her sols … who knows … Opportunity is also traversing new territory when it comes to robot life expectancy on Mars.

Despite her advanced age, whatever the numbers may be, this robot just keeps on going and going. “We can only hope to be as active and productive and useful when we get as old,” mused Callas. “When you think about Opportunity – it's like 'wow.'”

Once the robot field geologist passes through Lewis & Clark Gap, the MER team will say goodbye to Marathon Valley forever. “I think everybody on the team is going to be happy to get back on the road, and we’re all excited about what we'll see next,” said Golombek.

The three prime science directives of MER’s extended mission are:

1) Search for Matijevic Formation rocks that can reveal the environment prior to the impact that created Endeavour some 3.7 to 4 billion years ago during the Noachian Period on Mars;

2) Study the gully in Cape Byron in detail and determine whether it was formed by a river or stream, debris flow, precipitation, or perhaps even a lake that spilled over; and

3) Examine the Burns Formation rocks inside Endeavour Crater, which are several hundred meters lower in elevation than the Burns Formation strata that the rover has studied for more than a decade outside the crater, to see if they reveal a slightly different weather environment and if it was groundwater evaporating that formed them.

The rover that loves to rove does seem raring to go, as Squyres put it.

Carl Sagan with Viking Lander

Planetary Society co-founder Carl Sagan, an astronomer and professor at Cornell, and a Viking science team member, viewed biology as having the most to gain from planetary exploration, and he worked to incorporate exobiology (astrobiology) into the sciences. A Viking experiment tested the soil and found evidence for microbial life, and though the follow-ups failed to confirm the finding, the experiments are still being debated today. As Sagan would declare: “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” Still, he will be forever linked to another catchphrase. Though people like to note that Sagan said he never actually said “billions and billions," he did say “billion(s)” a lot in the Cosmos: A Personal Voyage series (PBS, 1980), and he did use the phrase “billions upon billions” in the book Cosmos (Random House, 1980). His distinctive way of pronouncing the word, with a punctuated ‘b,’ and his sense of romantic wonderment endeared comedians like amateur astronomer Johnny Carson and even musicians like Frank Zappa. In the end, a sagan came to be defined as “a unit of measurement equivalent to a very large number of anything,” and Sagan’s final book was titled: Billions and Billions: Thoughts on Life and Death at the Brink of the Millennium (Random House, 1997). See Sagan talking Cosmos on The Tonight Show.NASA / JPL-Caltech

“Opportunity is doing really well,” said Nelson. “We are essentially unchanged from last month and the month before that and so forth. Our mechanical systems continue to function very well. Our electronics are fine. Our imaging is fine. Everything is doing what it’s supposed to do.”

“The rover has remained in excellent driving condition since departing the north side of Marathon Valley,” added Seibert. “From a mobility standpoint Opportunity is ready to drive through Lewis & Clark Gap and begin the tenth extended mission.”

Soon, very, very soon, Marathon Valley will be, as the team members like to say, in the rear view mirror. Barring any more “interesting things” and if everything goes as planned, Opportunity will be taking us into new terrain and on a new adventure and next month will deliver another September to remember. “We're heading for the exit right now,” assured Squyres.

It was about this time 40 years ago that the first twin robots landed on the Red Planet and the Viking mission, a $1 billion dollar flagship mission composed of two orbiters and two landers, was commandeering the summer’s headlines. An extraordinary success Viking successfully blazed the first trails on Mars’ surface.

Less than a month after Viking Lander 1 touched down on July 20, 1976, the Associated Press and New York Times reported “scientists in Pasadena announced that the Viking 1 spacecraft has found the strongest indications to date of possible life on Mars.” An experiment designed to search for signs of life in the Martian soil had come out positive. But the subsequent control experiments came out negative, yet that experimental finding of microbial life is still being debated today.

Nevertheless, from the first surface images ever taken of the Red Planet, the Viking mission returned data that effectively constituted much of our knowledge about Mars for more than two decades. It was on this mission that MER’s Arvidson embarked on his first expedition to Mars, serving as the team leader of the Viking Lander Imaging Team from 1977-1982.

Finally in 2004, Spirit and Opportunity followed the Viking twins to the surface of our “twin planet,” landing three weeks apart in January 2004 in Gusev Crater and Meridiani Planum respectively.

Since then, Spirit and Opportunity have built on and added significantly to the body of knowledge that was gained with Viking, along with the efforts of orbiters Mars Odyssey, Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), and the European Space Agency’s Mars Express, and more recently, the roving mobile science laboratory named Curiosity.

Beyond uncovering evidence that supports the theory that Mars was once a lot like Earth complete with water environments, Spirit and Opportunity have sent home breathtaking panoramas, oversize “postcards” that reveal striking beauty in the desolate rusty red landscapes, images that have transformed Mars from a death planet into a friendly and familiar neighbor (if a bit “uncooperative,” even brutal one at times).

These days, 12.7 years after Opportunity dramatically scored the first interplanetary hole-in-one as she landed inside a small crater, Mars is fast becoming a serious human destination. Even though we’re not sure yet if we can keep humans alive long enough to complete a mission, the quest to put men and women on Mars has begun. The spacecraft has left the launchpad, so to speak, at least for the first mission. Would-be Mars explorers have signed up and are undergoing training. Just a few months ago Elon Musk and SpaceX entered into an agreement with NASA to send an unmanned Red Dragon mission to Mars as early as 2018.

Viking is “the giant on whose shoulders” all these Mars missions stand, and especially those that dare to land. The MER team decided last month to pay tribute to its predecessor, and in particular the first twin robots that landed on Mars by naming the final features in Marathon Valley after the rocks the two Viking landers checked out. It is an honor that means something right now in Mars exploration.

Flashing forward, perhaps 40 years from now journalists and newscasters looking back will have reason to remember Opportunity and the halcyon years on Mars. Maybe they’ll cite the endless stream of headlines about civil wars and terrorist attacks, whole scale devastation wrought from fires and floods and earthquakes during a long hot summer, hacked servers and emails and the death of privacy, and a maddeningly mad Presidential campaign. And then, perhaps, they’ll reflect on the irony in how a spirited little rover, a robot made of metals, composites, and electronics, about to embark on a brand new adventure far, far away on Mars, carried on, demonstrating the best of what humankind has to offer.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / Arizona State University

Goodbye Marathon Valley

The image above is a false color version of the MER mission’s panoramic view of Marathon Valley. The valley along Endeavour Crater’s western rim garnered its name because the rover’s arrival there coincided with her completion of the first marathon on another planet beyond Earth. Opportunity first entered the valley in July 2015 and will be departing the site in September 2016. The rover team calls this Sacajawea Panorama, in honor of the Lemhi Shoshone woman, whose assistance to the Lewis & Clark Expedition helped enable its successes in 1804-1806. Team members named many of the rocks and other features in Marathon Valley for members of the expedition officially known as the Corps of Discovery. This image was processed by Kelsie Crawford and Jim Bell, of ASU.Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth