A.J.S. Rayl • Dec 03, 2014

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Roves from Wdowiak Ridge into Network of Fractures

Sols 3829 - 3858

As a large, threatening regional dust storm blowing across the southern hemisphere of Mars continued to degrade and the skies over Endeavour Crater began to clear, veteran Mars Exploration Rover (MER) Opportunity successfully departed Wdowiak Ridge in November, maneuvering carefully through the rocky terrain around Ulysses Crater and getting back on the route south to the next major science attraction. But after logging her 41st kilometer, the Earth's longest-lived and most traveled robot on another planet drove into a network of fractures the likes of which the scientists had never seen before on Mars and wound up working there through the end of the month – and then something not completely unexpected happened.

Opportunity spent almost three months collecting data at Wdowiak Ridge and the small Ulysses Crater carved into its southern end, located along what remains of Endeavour's western rim. The robot field geologist is essentially now back en route to Marathon Valley, the next major science stop along the western rim, where orbital data indicate clay minerals, sure signs of ancient, non-acidic water, await.

"We finally left Wdowiak Ridge and were heading south with all deliberate speed to Marathon Valley, but when you see something juicy along the way, you stop and take a look," said Steve Squyres, MER principal investigator, of Cornell University. "This network of fractures lie both radially and concentrically to Endeavour Crater and are quite visible from orbit, and although they are not big chasms on the ground, they are very obvious features."

Opportunity roved right into one big fracture that extends from the plains of Meridiani west right into Endeavour Crater's rim and began checking it out. "It's most likely a fracture that was generated by the impact, whatever created Endeavour," said Ray Arvidson, MER deputy principal investigator of Washington University St. Louis. "We can see kind of a trough running uphill toward the crater rim and also running downhill away from the rim; some of these fractures extend out into the Burns Formation, which formed much later than Endeavour," he said.

While many of these fractures were formed by the impact during the Noachian Period on Mars when the Red Planet was a lot more like Earth, and have been "reactivated," others probably formed since Endeavour was created. "When one of these craters is formed, this big hole in the ground will then adjust itself gravitationally, [settling] in a process known as isostatic adjustment and during that process you can also have fracturing that takes place after the impact," Squyres explained.

No matter what happened at any point in the network, the fractures are potential signs of past water worth checking out. That's because fractures, in effect, serve as natural channels that "will tend to carry fluids, because fluids find the paths of least resistance," said Squyres.

In addition, fractures are more permeable. "If you had hydrothermal activity or groundwater activity, you would expect the fluids to preferentially move quickly along those fractures," said Arvidson, who took his 'maiden voyage' to the Red Planet on Viking back in 1976 and has accumulated more Martian dust on his khakis than any other Mars geologist.

Although the immediate hypothesis is that these fractures were most likely natural conduits for groundwater, the scientists are not discounting the possibility that surface water may have also flowed through these channels. "We're looking for both and whatever we find, we'll find," said Arvidson. "This is still a work in progress, but whatever we find, it will add to the story we're writing about what happened here."

Meanwhile, the dissipation of the regional dust storm that raised atmospheric opacity over Endeavour and concern among MER team members on Earth in October left the skies over Opportunity "summertime hazy," as Squyres described them. The rover dodged another life-threatening bullet and the sols ahead, at least for now, portend fair weather. "There is no major regional storm activity anywhere on the planet," noted Squyres.

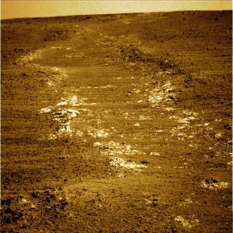

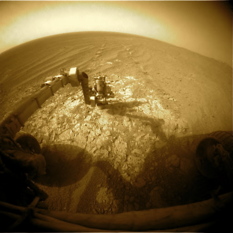

A fracture with a view

Opportunity roved into an extensive network of fractures in November as she was heading south toward Marathon Valley, the mission's next major science stop and the area where the robot will spend the next Martian winter. The robot field geologist drove into one of the largest fractures and examined a vein and surrounding bedrock up-close. The rover took this image with her Panoramic Camera (Pancam) on its Sol 3855 (Nov. 27, 2014) from her position inside the fracture, looking toward the rim of Endeavour Crater.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

Things haven't quite gone back to pre-storm conditions. This is the season of dust and Opportunity's solar arrays will likely not be as clean as they were just a few weeks ago for a while, maybe a good long while, maybe never. But the solar-powered rover's energy levels did climb back up to around half her full power production capability by mid-November, plenty of energy to drive and work.

"Life is good and the rover is in good shape," reported Bill Nelson, the chief of MER engineering, at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the NASA center that all America's Mars rovers call home. "She's experienced a couple of amnesia events and a number of Flash write anomalies, but these are more an annoyance than anything else and we've had no problems driving," he added just before the Thanksgiving break.

Getting out of Dodge – or Ulysses Crater's rock strewn, ejecta field was tricky though and the stormy weather conspired to delay Opportunity's departure from Wdowiak Ridge. That delay has impacted the mission's drive schedule and there is a push now to get to Marathon Valley. Still, MER is an exploration driven mission. "And we're like the young kid who sees something really cool and gets distracted on the way home from school," said Nelson.

Despite the mission's fractured distraction, the robot field geologist made decent tracks toward Marathon Valley, putting 456.85 meters (about 0.284 mile) in her rear view mirror in November. At month's end, she was that much closer to the site that will be her haven and campground throughout the next Martian winter – and another major achievement.

When Opportunity pulls up to Marathon Valley, the rover will have completed a marathon or 42.195 meters, which is why, of course, this site so christened. With that arrival, the aging veteran rover will make history again as the first robot on another planet to complete a marathon.

"We are now over 41.3 kilometers, so we're just under a kilometer from passing the marathon odometry," confirmed John Callas, the MER project manager at JPL.

"We're doing okay," said Squyres as he was heading out for the Thanksgiving break. "We've set ourselves a pace to follow to get to Marathon Valley with enough time to get significant science and exploration done there before we have to start dealing with our next Martian winter," said Squyres. "We're just barely on track right now to make it by the time we want to get there, so we want to be moving on soon."

But then, as Opportunity was finishing up work on the bedrock surrounding the fracture, she went into crippled mode, sending the rover ops engineers into a scramble to get their charge back in the saddle. They were equipped and ready. As of post-time, the ops team was preparing a plan for a pre-review Monday morning, December 1st, with hopes for a review and approval to initiate a reformat before the first week of December is out.

This delay will cause some concern among the scientists anxious to get to Marathon Valley, but the general consensus is that if any rover can make up for lost time, it's Opportunity.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

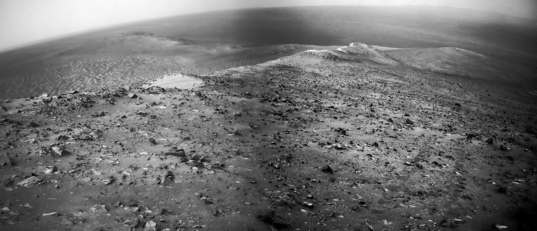

Looking back on Wdowiak

Opportunity spent almost three months collecting data at Wdowiak Ridge and the small crater called Ulysses carved into its southern end, located on Endeavour's western rim between Murray Ridge and Marathon Valley. The rover got back on the road in November, resuming her journey south to Marathon Valley. But as the rover departed, she paused mid-month to look back and take this image. Stuart Atkinson, MER poet, author, and member of UMSF.com, processed the raw, individual panels of pictures the rover took with her Pancam into this image. For more of Atkinson's pictures and musings on Opportunity's trek to and around Endeavour visit his blog, The Road to Endeavour.Opportunity's assignment for November was primarily to drive. As the dust storm continued to fade from concern and with the rover's power rising back to comfortable levels, the robot field geologist had been scheduled to drive out of October and away from Ulysses Crater and Wdowiak Ridge, and then kick it into high gear in November and begin making fast tracks to Marathon Valley.

Following two short and successful drives on October 29th and 30th, the robot's drive on Halloween, Sol 3829 (October 31, 2014) was terminated because of high slip after just 1.5 meters (5 feet). A coincidence? Or were the Martian goblins of fate at work?

While the MER ops team investigated, Opportunity greeted the dawn of November still somewhat stuck in the ejecta field of Ulysses Crater. Nevertheless, the rover continued working, snapping pictures of targets named Red Mountain, Pelham, and Sand Mountain, and engineering images of her surroundings with the Navigation Camera and Panoramic Camera (Pancam). In addition, the robot took care of some housekeeping, including "a full parameter dump," as Nelson put it, on Sol 3829 (November 1, 2014).

"We have tables of parameters for much of the mechanical and electrical equipment onboard," said Nelson. "These include current limits for the motors, stow positions for the arm and high gain antenna, and a host of other thresholds, positions and performance parameters." Among these tables are some things that change daily, he added. "For example, the tables with the rover position change every time the rover drives; the table of communication windows shrinks every time a comm window is used and expands every time we load the next few weeks’ worth of windows," he explained.

Escaping ejecta

Opportunity had to maneuver carefully through the rock and boulder-strewn ejecta field that surrounds Ulysses Crater in late October and early November before she could get back on the route south to continue her journey to Marathon Valley. The rover took this image with her Panoramic Camera (Pancam) and the Pancam team processed it the false color you see here, enabling the MER scientists to better distinguish differences among the rocks and other parts of the terrain.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

A parameter dump simply sends all the tables back to Earth. "We do this periodically to ensure nothing changed unexpectedly," said Nelson. "An errant cosmic ray, for example, could flip a bit." Typically, the rover dumps the parameters once every Earth year or twice in a Martian year, usually during the spring or fall, "because it ensures everything is ready for the more stressful seasons of summer or winter," he said.

Meanwhile, the MER ops engineers' careful assessment of Opportunity's terminated drive indicated that high slopes and loose soil caused the slip and that the rover was safe. Wasting no time, on Sol 3832 (November 3, 2014), the robot field geologist proceeded with a drive of about 32 meters (105 feet) and finally managed to exit Ulysses' ejecta field.

The following sol, 3833 (November 4, 2014) Opportunity drove on, heading south with a drive of 32.4 meters (106 feet). Two sols later, 3834 (November 6, 2014), the rover put another 40.25 meters (132 feet) behind her, and then wrapped the first week of the month conducting an atmospheric argon measurement with her Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS) on Sol 3835 (November 7, 2014) for the ongoing, mission-long study on the Martian atmosphere.

As the second week of November took hold, the robot field geologist pressed onward. On her Sol 3836 (November 8, 2014), she completed the first sol of a 2-sol Touch 'n Go using her Instrument Deployment Device (IDD) or her robotic arm to gather information on a surface soil target called Rock Creek, which just happened to be within reach. Following what has become protocol in her investigations, Opportunity took a set of pictures with her Microscopic Imager (MI) for a close-up mosaic of Rock Creek, and then placed the APXS on the same spot for several hours to glean its chemical composition.

The next sol, 3837 (November 9, 2014) Opportunity completed the Go, driving about 69 meters (226 feet) to the south, passing an outcrop the team nicknamed Huntsville along the way. During that jaunt, the rover's odometer turned over to 41 kilometers (25.48 miles) and the robot, once again, beat her own distance record. Last July, the MER team finally announced that Opportunity had officially surpassed the Soviet Union Lunokhod 2 rover's distance on the Moon back in the 1970s to become the most traveled robot off Earth.

"It never gets old," said Ashley Stroupe, one of MER's rover planners at JPL. "I don't even know what words to use to describe how this feels. We've learned so much more than we could have ever expected or hoped for and we're discovering new things all the time. Every record is exciting and we celebrate every milestone, because, having gone so far beyond anyone's dreams, we are aware that it could end at any moment."

Cruising by Huntsville

As Opportunity was driving south along the western rim of Endeavour Crater, en route to Marathon Valley, she passed by this outcrop, which the MER team calls Huntsville. Since Wdowiak Ridge, the rover's targets have been named after places in Alabama, in honor of the site's namesake, Tom Wdowiak, an original member of MER's Athena science team and professor emeritus of astronomy and astrophysics at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, who passed away unexpectedly in 2013. Although the team plans to start a new naming scheme soon, for now, Squyres said: "We're still honoring Tom Wdowiak even though we are off his ridge."NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

That noted, the MER team is confident Opportunity will add that other significant achievement waiting just down the road to her list of laurels. Certainly the rover that loves to rove seemed raring go as she drove on, mast held high, clicking off more meters as November progressed. "We're closing in on that marathon," Stroupe smiled.

The MER mission has been pulling off impressive feats, not to mention "miracles" since Spirit and Opportunity were in development. During the last decade, the rovers have reinvigorated, if not reestablished American engineering on the international stage and the MER team has become a model for planetary exploration, so much so that it's become easy to take this rover's achievements for granted.

But 41 kilometers – more than 25 miles – on Mars is an engineering achievement worth underscoring. Especially when one objectively considers Opportunity's age – 10.10 years and counting – and that the rover was "warrantied" for a 90-day tour with the mission-success driving objective set at 600 meters.

"I think we've done a good job maintaining the rover, and tracking everything, preserving all our consumables as best we can and that has all has been a big factor of course in the rover's longevity," said Stroupe. "But in some ways, Mars has been more kind to us than it has been harsh and we've been lucky."

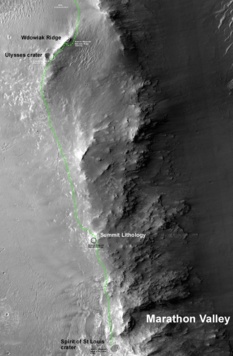

Opportunity's path south

Opportunity's planned route south to Cape Tribulation and Marathon Valley is charted here in green. As November 2014 came to an end, the rover had departed Wdowiak Ridge and finally escaped the ejecta field of Ulysses Crater to embark on the "long haul," as MER Deputy PI Ray Arvidson calls it, to the area marked Summit Lithology, the next intermediate stop on the journey to Marathon Valley.NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / NMMNHS

Indeed, at times over the years, Mars seemed to 'smile' on Opportunity, producing gusts of wind to clear her dust-laden arrays at critical times, among other things and Squyres from the beginning has mentioned the "lucky star" that seems to have shined on this mission. However, when one considers that the rover is essentially "a bucket of bolts," made up of and dependent on all kinds of parts, from lithium ion batteries to computer hardware and software to circuit boards and no end of wires that could break at any time, and that various single end failures could end the rover's "life" in a heartbeat – but instead every vital part has withstood the constant thermal cycling and harsh Martian conditions that the robot has endured, perhaps the better question is: how can Opportunity not be an engineering "miracle?"

At the end of the day, Opportunity's longevity looks to be a result of both "nature," humanmade that is, and nurture. By all accounts, this robot was built really, really well and the MER team has bonded with it and nurtured it in a way that is unique in planetary exploration, a winning combination that has obviously enabled the rover to keep on truckin', living longer and prospering more than seems possible.

While the MER engineers have no "bucket list" accomplishment for Opportunity past the marathon, they are considering some upgrades that could help the valiant old girl carry on more efficiently. "We are looking at possibly taking advantage of the some of the upgrades made to the Visual Odometry (VO) and the AutoNav software for Curiosity and implementing them on Opportunity to speed things up a bit and make things more efficient," said Stroupe.

Turning, for example: when Opportunity does a turn these days, she has to try to use the images produced with the VO software to confirm and correct her movements and/or slip. In order to get enough overlap for the images to be meaningful to the engineers, the process of turning has to be broken up into 15-degree segments. "Then after each segment, we do an update, which takes 3 minutes," said Stroupe. "A big turn can take a big chunk out of our drive time. If we need to turn 90-degrees, it can take 20 minutes just to do that."

With the upgraded VO software on Curiosity, the rover can point the camera at the same spot on the ground as it turns. During that one big turn, the software tracks all of the rover's slip at once. "It's not just faster, but it's more accurate because you don't get all the cumulative error of all the individual updates. Rather, you just get a single update," Stroupe explained. "That new VO software would speed us up tremendously."

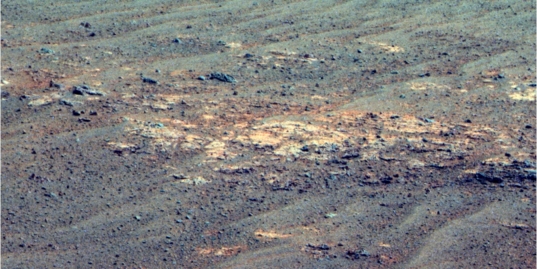

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

The fracture on approach

Not long after resuming the journey south to Marathon Valley, Opportunity roved upon a serious network of fractures. Since fractures are natural conduits for water, the scientists commanded the rover to make a science stop right in the middle of the big fracture pictured above, which extends from the rim of Endeavour Crater out to the plains of Meridiani Planum. "It's most likely a fracture that was generated by the impact that created Endeavour," said MER Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson. The rover shot the fracture with her Pancam as she was on approach, and the Pancam team processed it into this false color image.On Sol 3839 (November 11, 2014), Opportunity continued her push south with a 113.66-meter (372.90-foot) trek. She drove the first portion "blind" or on her own, and then used autonomous motion for the final part. Following the mission's scientific protocol, the rover took pre-drive targeted imaging and post-drive panoramas before and after each drive segment. Two sols later, 3841 (November 13, 2014), she continued her journey and put another 77.05 meters (254.26 feet) on her rocker bogie.

By mid-November, as the dust from the large regional storm of October was raining down, the skies over Endeavour were getting lighter and the Sun was shining a little brighter. The rover's solar array power production had climbed above 500 watt-hours and her dust factor was still strong, hovering around a 0.713. Meanwhile, the atmospheric opacity or Tau had dropped down from a scary high of 2.14 in October to a you-can-breathe-again 1.474.

During the third week of November, Opportunity and her rover planners (RPs) did something a little bit different as they scheduled back-to-back drives. Of course, driving two or even three sols in a row is nothing usual for this rover, but this time the RPs sequenced them at same time. "Normally we only sequence one drive at time and we don't do multi-sequence," Nelson pointed out.

Opportunity made it look easy logging 39.40 meters (129.26 feet) on Sol 3843 (November 15, 2014), and 40.38 meters (132.40 feet) on Sol 3844 (November 16, 2014). But even when things are rolling right along, stuff happens.

After the drive on Sol 3844, the rover suffered an overflow in its buffer on Mars Odyssey (ODY), the orbiter on which it primarily relies for getting its data back to Earth, and lost about 7.8 megabits of data, said Nelson.

The Odyssey buffer is RAM and is a ring buffer. "Like all ring buffers, it starts [writing data] at the next open space and continues to the end; the data that follows starts at the beginning and writes over previous data, as if writing around a ring," Nelson explained.

The buffer is never cleared. Instead, new data overwrites the old data. "But if new data exceeds the buffer size, it writes over earlier new data and that's a buffer overflow and that's what happened on Sol 3844," he said.

While it was not desired, it was not a disaster. The mission moved on. The MER scientists were intently focused on a network of fractures just ahead of Opportunity and Sol 3846 (November 18, 2014), the rover put another 9.92 meters (32.54 feet) in the rear view mirror and herself right smack in the middle of one of the largest fractures.

In the fracture

This is a raw partial-selfie that Opportunity took this with her hazard camera after she drove into the fracture the mission spent the latter part of November studying. The robot field geologist checked out a vein that turned out to be calcium sulfate just like Homestake, and also examined the surrounding bedrock and found that it features a "curious" unusual composition, according to MER PI Steve Squyres. But the details are still to come.NASA / JPL-Caltech

There was a lot to do and the robot field geologist got to work right away on a vein the team named Cottondale. "It looks similar to the calcium sulfate vein Homestake we found over at Cape York," said Squyres, "but you don't know for sure until you make a measurement."

Opportunity looked at Cottondale up close with her MI and APXS on Sol 3848 and the following sol, 3849 (November 21, 2014), moved to an offset position and repeated the scientific investigation on Cottondale2. "This vein is like Homestake, a calcium sulfate vein and probably gypsum," said Squyres. "We're pretty convinced Homestake is gypsum and this is likely to be the same thing."

Late that evening (November 22, 2014 on Earth), after several weeks of smooth operations with none of the recurring issues involving her Flash memory, the rover suffered a bout of amnesia when she failed to launch her Flash memory drive. Although that meant that the APXS data on Cottondale2 stored in the rover's Flash memory was lost, the rover, as usual, recovered that data, which is always also saved in the APXS's system, and sent it back to Earth.

This time, the MER team wasn't as annoyed by the amnesia event, because for the first time, the robot implemented a more advanced diagnostic procedure for amnesia events, reported in last month's MER Update. "Basically, we have the rover write a note to itself when it has an amnesia event, kind of like the character in the movie who writes long notes to himself about what happened," said Callas. "Before, all we did was set a flag [in the system] to tell us when an amnesia event happened. This time, we copied the data products from the amnesia event into EEPROM, which is a separate non-volatile memory that is normally not used for this purpose. So we'll see what that tells us."

Despite the urge to rove on, the MER mission decided to have Opportunity stay put and work in the fracture through the Thanksgiving holiday and to the end of the month. The science stop served several purposes. For starters, the mission has never encountered any fracture network as extensive as this one. Also, the rover was going into restricted sols when driving is limited, plus there was a substantial backlog of data onboard the rover. "We have a lot of data in Flash that we need to get down and we also want to do some good color Pancam imaging looking uphill at the trough and downhill at the trough," said Arvidson. "I'm not sure we'll find anything particularly extraordinary here, but what we do find will definitely be another piece of the puzzle."

On Sol 3850 (November 22, 2014), Opportunity moved just a little to a target on the bedrock immediately adjacent to the fracture, homing in on a target spot dubbed Calera. But around noon local Mars time, she suffered three Flash write errors. Although the rover recovered quickly, late that night (November 23, 2014 on Earth) she suffered another amnesia event. "We hadn't had any amnesia events for about 4 weeks and then we had two of them back-to-back," Callas noted.

Since Opportunity had just suffered a bout of amnesia the sol before, this second one was not recorded with the new diagnostic procedure for the simple reason that there is just not enough room in EEPROM to safely record more than one event at a time. Moreover, at this juncture, the engineers aren't sure of what they will find in that data, whether there will be a clue as to why this continues to happen after the Flash reformat in September or not. The MER engineers would receive that data late on November 26th, but there is no word yet on what is or isn't there. The good news is that neither amnesia events, nor the Flash write errors caused a sudden reboot, according to Nelson.

Cottondale up-close

Opportunity took this close-up mosaic of Cottondale, a vein inside the fracture she drove into in November, with her Microscopic Imager. Turns out, Cottondale is a calcium sulfate vein just like Homestake, just as the MER scientists suspected, and "probably gypsum," said MER PI Steve Squyres. This raw image has been tinted.NASA / JPL-Caltech

Opportunity woke up the next sol, 3851, and went right back to work. After brushing Calera with her Rock Abrasion Tool (RAT), the robot field geologist then completed the investigation with the usual analysis of its chemical composition with her APXS. Then, the rover moved to another nearby target on the bedrock called Locust Fork. "We did a brush and will do APXS over the holiday," Squyres said just before the Thanksgiving break began on Thursday, November 27th.

Since Wdowiak Ridge, the rover's targets have been named after places in Alabama, in honor of the site's namesake, Tom Wdowiak, an original member of MER's Athena science team and professor emeritus of astronomy and astrophysics at the University of Alabama at Birmingham who passed away in 2013. "We're still honoring Tom Wdowiak even though we are off his ridge now," said Squyres, "We'll start on a new naming scheme soon."

The first indications from the APXS data that has been downlinked are that the bedrock around the fracture features a "curious" unusual composition. "It has some interesting oddities to it that could be an example of alteration by hydrothermal fluids or whatever flowed through here, but that is pure speculation on my part right now," said Squyres. "I can't give you details, because I don't have details yet."

Some details, however, are known. The bedrock is fundamentally basaltic in character like much of Mars geology. Also, the evidence for past water that Opportunity has uncovered at Meridiani is primarily associated with the rising groundwater, with recharge from the southern highlands, as Arvidson has pointed out.

A natural assumption then would be that whatever flowed through this network of fractures long, long ago was most likely subsurface water or groundwater, known as fracture flow. But it could be that surface water also flowed through the fractures.

"We know that most likely the Burns Formation, which was [formed] later on [after the Endeavour impact and the Noachian Period], certainly involved rising groundwater," Arvidson said. "But the erosion of Endeavour and the overall crater terrain occurred during that earlier Noachian Period, which is associated with runoff, water coming from the atmosphere down, so we're looking for evidence of that too. It's just still a little too early to tell what's going on."

Checking out Calera

After examining the vein called Cottondale inside the fracture, Opportunity turned her attention to the bedrock around the fracture and got to work on a target called Calera. It could hold evidence of alteration by hydrothermal fluids or water or whatever appears to have flowed through here, but the data is still coming in. The rover took this raw workselfie with her Pancam. It has been tinted for better detail.NASA / JPL-Caltech /Cornell / ASU

As November began to wind down, the Martian summer began bringing temperatures up at Endeavour. Even though Mars could whip up another dust storm at any time, for now Opportunity continues to see dust levels slowly return to seasonal expectations. From 2.14, one of the highest Taus recorded on the entire MER mission, the atmospheric opacity improved to 1.4 toward the end of the month and the rover was able to consistently produce 400 to 500 watt-hours of power. As expected however, the dust factor did deteriorate a bit more with levels dropping from around .74 to around .65. It's no surprise. The powdery stuff is steadily "raining" from the skies and presumably steadily coating the rover's solar arrays.

"I'm hoping when we get to the summit lithology site we will have more cleaning events to get some of this dust off Opportunity's arrays," said Nelson.

The spot labeled Summit Lithology on the MER maps happens to be the next intermediate stop on Opportunity's journey to Marathon Valley, and the rover could get lucky again. Certainly the rover's own experience has demonstrated that summits and ridges are good zones for getting dusted off.

Earlier this year, Opportunity emerged from Cook Haven, her winter haven just off Murray Ridge, cleaner than she had been since her first winter on Mars back in 2005. The scientists however don't really know much about Summit Lithology and they have yet to actually give it a "real" name.

"We'll name it soon and find out what it is when we get there," said Squyres. "But it looks like the next place along the road to Marathon Valley where we might make a serious stop."

It's a balancing act for MER right now between science and driving. Despite the fact that Opportunity is sitting in the first big fracture and extensive network of fractures that the mission has encountered, the team is anxious to keep moving on. For months the plan has been to get to Marathon Valley with a lot of time to spare so the robot field geologist can explore the area before the next Martian winter begins.

"But we have been measuring how far we have actually traveled in the direction of Marathon Valley and found that we weren't making the progress we felt we needed to be there on time," said Nelson. "So the plan is to continue to concentrate on driving in December."

The next Martian winter is still about one Earth year away. "We're solidly in Martian summertime right now, so we're a ways off, but we're thinking ahead, right?" said Squyres. "What I don't want to do is dawdle so much on the way to Marathon Valley that the first thing we have to do when we get there is find a north-facing slope and hunker down for the winter. I want to have significant time for exploration just as we had at Matjevic Hill."

Once Opportunity arrived at Matijevic Hill in August 2012, the scientists quickly realized they had roved into a scientifically significant site. "We looked at Kirkwood / Whitewater Lake for a bit and then we did that long walkabout to survey the hill carefully, to find out what's where and to get the lay of the land," Squyres said.

Next stop: The summit

Despite the science stop at the fracture, Opportunity managed to put 456.85 meters or around 1/4 mile in her rear view mirror. And that put the next intermediate waypoint into view. Labeled Summit Lithology on the team's overhead maps, it is circled on this image that the rover took toward the end of November and which Stuart Atkinson processed and produced.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

By the time Opportunity completed her work at Matijevic Hill in 2013, the mission discovered that Whitewater Lake was the oldest bedrock ever found on Mars, dating to the Noachian Period 3.7 to 4.1 billion years ago, and characterized the geological setting for two kinds of clay minerals detected several years before by the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, evidence for past near neutral water.

"We think there may be something comparably important at Marathon Valley and we want to have enough time to do there what we did at Matijevic Hill," said Squyres. "And Marathon Valley is significantly larger than Matijevic Hill is, so it's going to take some time."

Opportunity was slated to "button up" after the long Thanksgiving weekend, put the pedal to metal and cruise south as December dawned, but she went into crippled mode on Sol 3857 (November 29, 2014) and again later it appears on Sol 3858 (November 30, 2014). "We appear to have gone into permanent crippled mode," Nelson reported. "In this mode, a problem with the Flash memory prevents creation of a Flash drive. The flight software, the operating system, then creates a RAM drive. The RAM drive is both smaller, about 1/10th the size of the Flash drive, and volatile, so all contents are lost whenever the rover naps or DeepSleeps."

The difference between an amnesia event and crippled mode is that with an amnesia event data stored in the RAM drive is lost before it can be downlinked and that creates a blank spot in the telemetry, explained Nelson. "The rover must be in crippled mode and have no downlink to create an amnesia event. If in crippled mode but with a downlink, there will be no 'hole' in at least some of the telemetry; therefore it is not classified as an amnesia event," he said.

As bleak as permanent crippled mode sounds, it's "not that bleak," said Nelson. "Recall that Spirit finally went into a persistent crippled mode in 2009 and a reformat fixed the problem." Although Opportunity has a slightly different history with regard to her Flash issues, another reformat "may do the trick," he said. "Even if we were forced to operate only in crippled mode, we could manage," he added. "It gates how fast we take data since we can’t store it for later transmission, but we would still have an active mission."

Before the Sun set on November however, the MER team was working hard, pulling together a Flash reformat plan for a pre-review Monday, December 1st, and a full up review three days later. In the meantime, if possible, Opportunity will try to recover the APXS observations on Locust Fork and other planned Pancam images not acquired over weekend," said Arvidson.

Once that is done, the plan remains the same: get back on the road. The rover has about 400 meters (about 0.25 mile) to go to get to Summit Lithology. From there, it is only 500-550 meters (0.31-0.34 mile) to Spirit of St. Louis Crater. "That's at the entry point to Marathon Valley and goodness know what's that's going to look like," said Squyres. "We do want to get moving."

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

Wdowiak Panorama

Opportunity bid adieu to Wdowiak Ridge in October and finally escaped the ejecta field of its Ulysses Crater in November 2014. In honor of MER Science Team Member Tom Wdowiak, who passed away in 2013 at the age of 73 and who is much missed, the MER Update wanted to present the panorama the rover took from his ridge one more time. "Wdowiak Ridge was a big deal for us," said MER PI Steve Squyres. "It's one of the milestones that really matters. Stuart Atkinson "stitched" the panels of images the rover took with her Pancam together and processed them in the Martian Technicolor version here.Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth