Jason Davis • Feb 09, 2017

Want NASA to pick your space mission proposal? Two winning scientists share some tips

It was 8:00 a.m. on January 4, 2017 when Lindy Elkins-Tanton got a phone call from NASA saying her proposed mission to send a spacecraft to a metallic asteroid had been selected.

Elkins-Tanton, the director of Arizona State University's School of Earth and Space Exploration, had just wrapped up a busy 2016. She was taking a well-earned, two-and-a-half week vacation in western Massachusetts, where she was reading academic papers and novels, and trying to get in a little snowshoeing.

Her mission, Psyche, was one of five finalists in the current iteration of NASA's Discovery program, which selects low-cost planetary science missions from a whittled-down pool of applicants.

First, NASA told the finalists to expect a decision the week after New Year's Day. Then, Elkins-Tanton was told to expect a phone call between 10:00 and 11:00 a.m. on January 4.

The call came early. She was still asleep—and slightly embarrassed about that. When she picked up the phone, it was Thomas Zurbuchen, the head of NASA's science division.

"He knew right away I'd been asleep," Elkins-Tanton told me recently. "He said, 'Oh, I think I've wakened you. But I think you're going to be happy that I've wakened you.' So I knew right at that moment that we won. I was out there in the hills, in the snow, getting this phone call from NASA. It was really surreal."

The phone call Elkins-Tanton received was the culmination of a process that officially started in November 2014, when NASA announced it was accepting proposals for its next Discovery mission.

Discovery missions are cost-capped at about $500 million, not including launch and operations costs. There is also a second competitively selected mission type called New Frontiers, which gives winning missions a budget of around $800 million, including the price tag of a rocket.

Right now, NASA is accepting proposals for its next New Frontiers mission. They're due in April, and in November, three winners will get funded for further studies. NASA plans to make a final decision on which mission will fly in mid-2019.

The process is not for the faint of heart. Scientists and engineers can spend years toiling over a proposal, only to have their hopes dashed by the selection process.

I wanted to learn more about why some missions succeed and some don't, so I asked two recent winners how they pulled it off. It turns out that while both missions had slightly different recipes for success, there were a lot of similarities: intangible assets like good team chemistry and a knack for navigating the science community landscape can be just as important as the nuts and bolts that make up a spacecraft.

Third time's a charm for OSIRIS-REx

The last New Frontiers mission to launch was OSIRIS-REx, which blasted off in September to collect a sample from asteroid Bennu.

It would actually be more accurate to say the journey of OSIRIS-REx began 13 years ago. In 2004, Michael Drake, the former head of the University of Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory in Tucson, wanted to propose an asteroid sample return mission. Drake asked LPL colleague Dante Lauretta, who was an untenured, assistant professor at the time, to become his deputy principal investigator.

Drake and Lauretta pitched the mission to NASA's Discovery program. They weren't selected, and NASA gave the proposal the lowest possible grade: category four.

"Category four means you're rejected and they shouldn't even need to tell you why," Lauretta said during a recent phone interview. "We were pretty naive back then, I'll admit."

The mission science, he said, was compelling. "But the technical management and cost needed a lot of work."

Ultimately, NASA didn't select any Discovery missions that time around. When the agency asked for new proposals a year later, Drake and Lauretta decided to try again.

This time, Lauretta worked closely with engineers at Lockheed Martin, in an attempt to better synchronize the mission's science and engineering aspects. He wanted to understand every aspect of the spacecraft, and ensure the Lockheed team understood every part of the mission science.

"I really learned how spacecraft are put together," Lauretta said. "But, most importantly, I learned how you translate science into engineering-speak, because they really are different languages."

Drake and Lauretta made it to the final round, but ultimately lost to GRAIL, a pair of lunar gravity mapping probes that launched in 2011. On the bright side, NASA said the asteroid mission's science and engineering was solid—the problem was that it was getting too expensive.

In 2008, the National Academy of Sciences prepared to release an interim update to their 10-year Decadal Survey, which lays out acceptable mission themes for the mid-cost New Frontiers program. An asteroid sample return mission had not been prioritized in the last Decadal Survey, so Drake and Lauretta's team started pitching the benefits of such a mission to the science community. They also demonstrated how they could overcome any potential engineering challenges.

The Academy was convinced. When the interim report was released, "Asteroid Rover/Sample Return" was listed as a mission theme. The next New Frontiers proposal was due in 2009, so Drake and Lauretta tweaked their proposal and applied. This time, they won, beating out a lunar sample return and a Venus mission.

Asteroids beat Venus again

When compared with OSIRIS-REx, the origin story of Psyche is a bit simpler.

In 2011, Lindy Elkins-Tanton was the lead author of a paper on the diversity found among different types of asteroids.

"We all have this image of asteroids that kind of comes from Star Wars, and doesn't actually reflect the truth," she said. "I got an e-mail from some colleagues at JPL (NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory) asking whether I'd be interested in helping design a mission to test our hypothesis."

Might NASA decide to send a spacecraft to an asteroid unlike anything scientists had ever seen? Elkins-Tanton was intrigued, and as the mission concept came together, her team started looking at targets. Very quickly, Psyche—a metallic asteroid that may have iron-nickel spires jutting into space—ended up as a prime target for the spacecraft. The asteroid was so compelling, the team ultimately named their mission Psyche as well.

Whereas it took Drake and Lauretta three tries to get OSIRIS-REx on the launch pad, Elkins-Tanton was fortunate—Psyche was selected the first time.

"I kind of feel guilty because we won the first time through the proposal process," she said. "That's rare."

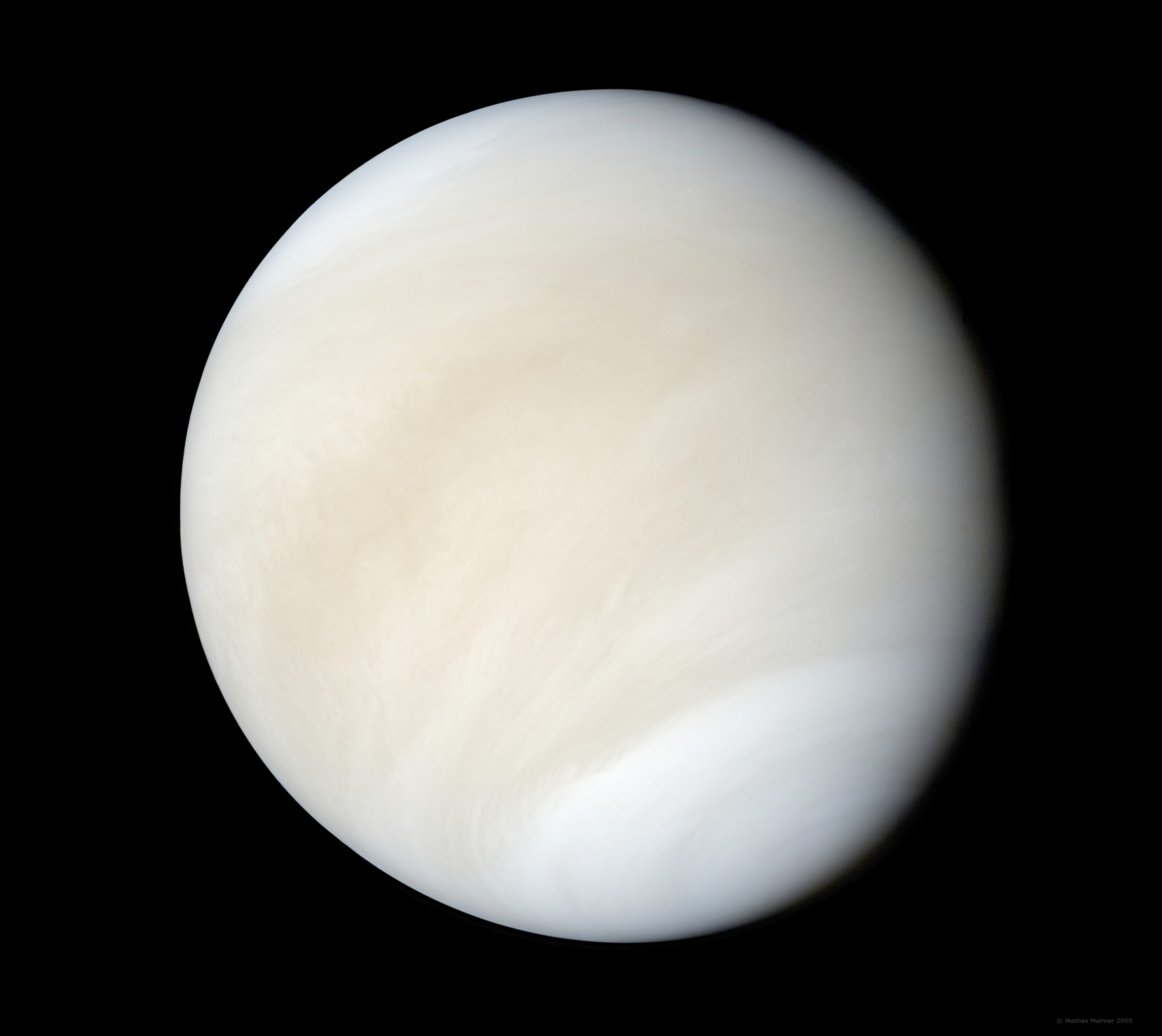

Psyche was selected alongside another asteroid mission called Lucy. Once again, asteroids triumphed over Venus.

"As totally, unbelievably thrilled as I am that we won, I feel heartbroken that we're not going to Venus right now," said Elkins-Tanton. "My big hope is that an even better Venus mission, with a higher dollar value will go."

The currently allowed New Frontiers mission themes are Venus, a lunar south pole sample return, a comet surface sample return, an ocean worlds (Titan and/or Enceladus) mission, a Saturn probe, and a Trojan asteroids tour.

NASA is already working on a high-dollar mission to another ocean world: Europa. The aforementioned Lucy spacecraft is headed for Jupiter's Trojan asteroids. Cassini is currently operating around Saturn—which includes Titan and Enceladus—though the aging probe's mission ends later this year. This leads many to believe Venus already has an advantage over the competition. NASA hasn't sent a spacecraft there since the Magellan probe, in 1990.

"Venus has had a rough time," Lauretta said. "I don't think anybody at NASA or anywhere else disagrees that the science is really exciting. It's just that the technical risks are so high. It's not a friendly environment to operate in, especially for a surface package."

Good team chemistry

A team proposing a mission to Venus will have to convince NASA their spacecraft can survive in one of the harshest places in the solar system. The planet's surface is hotter than Mercury, air pressures are equivalent to operating almost a kilometer under Earth's ocean, and winds in the upper atmosphere are stronger than an Earth-based tornado or hurricane.

Engineering competency aside, what gives one team's proposal the edge over another? Both Lauretta and Elkins-Tanton were in agreement that fostering a positive team chemistry was absolutely vital. NASA wants to see groups that are cohesive and relaxed, where everyone has a voice.

And no negative nellies.

"One loud, negative voice can turn the tide of everything," Elkins-Tanton said. "It can cause people who feel more timid to shut up and not share things that are important and critical."

Projecting confidence is also important. Prior to NASA's onsite visit, Elkins-Tanton hired a speaking coach to visit her team for one afternoon. "It turned out to be really helpful to turn our minds away from the super-minutia that we'd been obsessed with for years, and out to the larger story for people who were going to care about it," she said.

Lauretta said one strategy he used for unifying his team was making sure everyone knew everyone else's role, and who the expert was on any particular topic.

"When you see missions that get into trouble, a lot of it is because of dysfunctional teaming," he said. This particularly shows in documents like the mission's concept study report, which, in the case of OSIRIS-REx, was about 2,000 pages.

"If you don't have a coherent team that's communicating well, that document is going to be a mess," said Lauretta. "NASA's going to be like, 'Wait a minute. If they can't communicate enough to make this document consistent, how on Earth are they going to pull off something as complicated as building and launching a spacecraft?'"

The competition

Because Discovery and New Frontiers missions are competitively selected, teams pay close attention to what other contenders are doing. Elkins-Tanton said this is particularly the case among missions heading to the same destination, such as Venus.

To prevent other teams from "ghosting" aspects of their own proposals, many groups work in secrecy.

"A lot of the proposals are top secret, and nobody even knows they're happening," she said. "There were proposals that we didn't even hear a rumor about until after they were all submitted, and more news started leaking out."

The Psyche team, however, took a different approach.

"We thought that probably a lot of people, even in planetary science, didn't understand what an amazing, unique, improbable object Psyche was," Elkins-Tanton said. "So we decided that we needed to be public about what we were doing." This included conference talks and workshops on asteroid differentiation.

Her team also developed artist's concepts to show off how the asteroid might look. This had the dual benefit of exciting the Psyche team itself, and helping its members visualize where they were going.

Lauretta said the OSIRIS-REx team wasn't as focused on publicity, except when it came to demonstrating why the National Academy interim report should include an asteroid sample return mission. But during the proposal process, Lauretta said his team often highlighted how OSIRIS-REx was different, especially when it came to other missions' weaknesses. If there was concern over the operating environment on Venus, for instance, the OSIRIS-REx team might highlight how comparatively benign Bennu was.

It takes a village

By the time OSIRIS-REx was selected in May 2011, Michael Drake's health was suffering. Lauretta started to assume a de facto principal investigator role, and Drake passed away that September.

"It was emotionally and incredibly personally draining," Lauretta said. "He was a mentor and a friend. I still miss him dearly and I really wish he was here to see everything we have accomplished at this point."

Lauretta knew he would need his family's help if he were to fill Drake's shoes permanently.

"That was a big conversation I had with my wife," he said. "I said, 'I'm going to try to go do this. I need to know if you're on board with it, because if you think it's going to disrupt the family, then I'll back off.'"

In the end, support came not just from his immediate family, but his extended family—on everything from child care to help around the house.

Elkins-Tanton managed to lead her Psyche team through the proposal process while holding down a full-time directorship job at ASU.

"I calculated that in the last two years I've had less than one day off per month," she said. NASA advisors have already told her to expect 80 to 100 percent of her work time will be consumed by the mission as it proceeds from development toward launch. She is currently exploring how to shuffle her responsibilities to make way for what will become an entirely new career path.

The politics of rocket science

Now that OSIRIS-REx is safely on its way to Bennu, Lauretta's schedule has opened enough for him to teach a class again. This semester, he's leading a course on spacecraft mission design and implementation, trying to pass on lessons he has learned to the next generation of would-be principal investigators.

His students are currently designing a New Frontiers-class mission to Titan. Everyone in the class was assigned a mission role, from principal investigator to business lead.

But before the students started designed their spacecraft, Lauretta led them through a crash course on space policy. They learned about the federal budget, the roles Congress and the White House play, and what different assessment groups do.

This philosophy—that successful missions depend on sound social strategies as much as they do engineering and science—is also reflected in Lauretta's Xtronaut board game, which teaches players the logistics behind space missions. Xtronaut has been such a hit, Lauretta has expanded it into an upcoming successor game, as well as a series of STEM education programs.

He also had his students read through a recent NASA authorization bill that passed the Senate in 2016.

"I said, look at what's in here," he told me. "Mars 2020. Europa. How do you think that got in there? Somebody in the science community decided these are important missions."

Lauretta leadership principles

As part of his spacecraft mission design and implementation class, Lauretta shared ten leadership principles he has learned after spending five years at the helm of the OSIRIS-REx program:

Reward initiative

Value capabilities over credentials

Share the credit / take the blame

Assume good intentions

Cultivate diversity and seek out different perspectives

Work the problem

Make the hard decisions

Admit mistakes

Show appreciation

Keep temper under control (easier said then done when the stakes are high)

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth