Jason Davis • Jul 18, 2016

Horizon Goal: A new reporting series on NASA’s Journey to Mars

On the morning of February 1, 2003, space shuttle Columbia zipped over the California coast at a height of 44 miles, traveling 23 times the speed of sound.

The shuttle was coming home after a 16-day mission. In just a few minutes, it would be on the other side of the United States, landing at Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

At the runway, NASA administrator Sean O'Keefe waited patiently with Columbia's crew families. O'Keefe, a cost-cutter who previously held top financial positions with the Navy and Department of Defense, had just spent the past year working to erase a $5 billion cost overrun for the fledgling International Space Station program. The space shuttles were vital in getting the new orbital laboratory up and running, and they would continue on in that role as the rest of the ISS was assembled.

Suddenly, communications with Columbia were lost over Texas. The landing countdown clock hit zero, but the shuttle didn't arrive. Then, news channels began broadcasting footage of debris falling from the sky.

Columbia, along with its seven crew members, was gone. A stunned O'Keefe left the landing strip to notify president George W. Bush.

"It was terribly emotional, very tragic, and very difficult to work through," O'Keefe told me recently.

Introducing Horizon Goal

Flash forward thirteen years, to 2016: The shuttles are retired. The ISS is complete, and NASA relies on private companies and international partners for station crew rotations and cargo shipments.

NASA's "horizon goal"—a term popularized by the National Research Council in 2014—is Mars. The space agency is building a giant rocket called the Space Launch System and a crew capsule called Orion to take humans there in the 2030s.

NASA serves at the behest of the government's executive branch, with oversight by Congress. With the country on the brink of its first presidential transition in eight years, what is the status of the world's largest human spaceflight program? How did the current plan come to be, and where will it go from here?

We're going to find out.

Today, The Planetary Society, the world's largest non-profit space advocacy group, is embarking on a multi-part reporting series with the Huffington Post that will explore these and other topics.

And according to Sean O'Keefe, the day Columbia fell from the sky is a good place to start.

Columbia's aftermath

Like Challenger in 1986, Columbia's fatal blow came during launch, as the vulnerable shuttle rode to orbit alongside a roaring rocket stack. Traditional capsule systems place the crew at the top of the rocket, where they can be encased in a protective shroud and blasted away from a faulty rocket at a moment's notice.

During Columbia's ascent, a piece of dislodged foam from the shuttle's external fuel tank struck the orbiter, punching a hole in its thermal protection system. Upon atmospheric reentry, hot plasma seeped into the shuttle and tore it apart.

By 2003, NASA had already started to contemplate what might come next after the shuttle, but Columbia moved that discussion to the forefront. And with that discussion came some serious soul-searching about sending people into space.

"It was a very catalytic event," O'Keefe said. "It did focus everybody's attention, across the board, whether they were in the White House, in NASA, or on Capitol Hill. It brought this into a stark reality of asking very important and significant questions: What's the point of this? What are we really trying to do here?"

"Going beyond the completion of the station, there was no forward plan," said Mary Lynne Dittmar, a former Boeing ISS flight operations manager who now serves as the executive director for the aerospace industry-led Coalition for Deep Space Exploration.

"NASA had been drifting from presidential administration to presidential administration," she said.

A new vision for space exploration

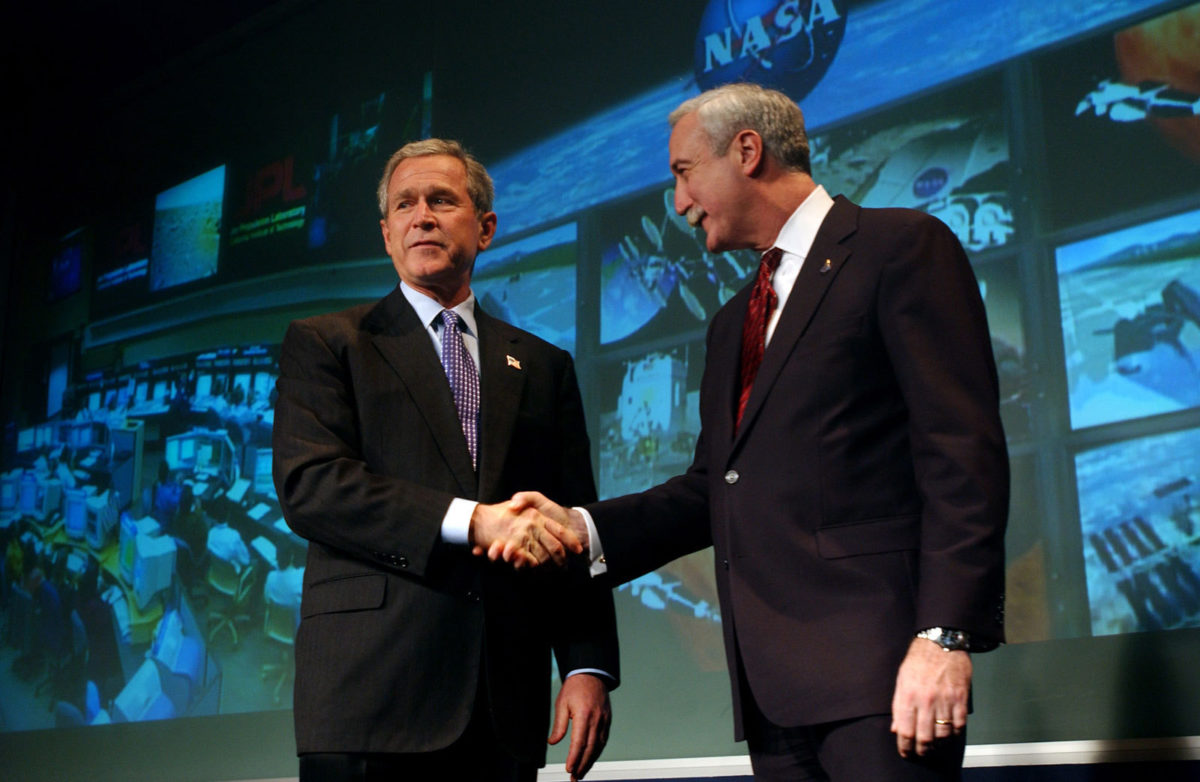

On January 13, 2004, less than a year after the Columbia disaster, President Bush made the two-mile trip from the White House to NASA Headquarters in Washington to deliver a speech on a new direction for NASA's human spaceflight program. The plan became known as the Vision for Space Exploration, or VSE.

"In the past 30 years, no human being has set foot on another world, or ventured farther upward into space than 386 miles; roughly the distance from Washington, D.C. to Boston, Massachusetts," Bush said. "It is time for America to take the next steps."

The VSE called for returning the remaining space shuttles to flight as soon as possible, and using them to complete the ISS by 2010. After that, the fleet would be retired.

In the meantime, a new deep space crew vehicle would be developed and readied for astronauts by 2014. By 2020, NASA astronauts would ride the vehicle to the moon and establish a semi-permanent presence that would serve as a jumping-off point for other destinations, including Mars.

A bold plan, with details TBD

At that point, the ISS was slated for retirement around 2016, which would free up funds for the proposed moon missions. Standing down the shuttles in 2010 would create a six-year gap in which America could not access the ISS—later given a price tag of $75 billion—on its own.

Instead, NASA would fly crew and cargo to the space station through "the purchase of services for cargo and crew transport using existing and emerging capabilities, both domestic and foreign." That's an apt description of how NASA currently buys astronaut seats from Russia, while relying on the private space firms SpaceX and Orbital ATK for cargo shipments.

As for the new crew vehicle, how would it be launched? And what would carry all of its accompanying moon landing hardware to orbit?

If NASA didn't build a new rocket, it would have to buy one. The possibilities included Lockheed Martin's Atlas V and Boeing's Delta IV, which were used primarily for Department of Defense payloads.

Neither launcher was certified to carry humans. Some experts doubted the necessary redundancies and safety measures could be added—at least, not without enormous costs. (Thirteen years later, the joint Boeing-Lockheed company United Launch Alliance plans to use the Atlas V to launch astronauts in Boeing's CST-100 Starliner spacecraft.)

On November 1, 2004, O'Keefe gave a speech aboard the historic USS Constellation in Annapolis, Maryland. Drawing parallels between the Vision for Space Exploration and the ambitions behind the ancient sailing ship, he named NASA's new human spaceflight program Constellation.

"Today, we help continue that tradition by accepting the spirit of the original Constellation and proudly transferring it to the class of space vehicles that will carry humankind back to the moon, Mars and beyond."

A month and a half later in December, O'Keefe tendered his resignation as NASA administrator to take a job as the Chancellor of Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge.

Constellation would take shape under someone else's watch. In part two of our series, we'll look at how the program unfolded under new NASA leadership.

Support our space reporting

Want to learn when new Horizon Goal story segments are posted? Follow The Planetary Society on Twitter, or visit our Horizon Goal microsite, where we're co-publishing the series.

You can also support The Planetary Society's reporting efforts by becoming a member today.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth