Jason Davis • Nov 14, 2014

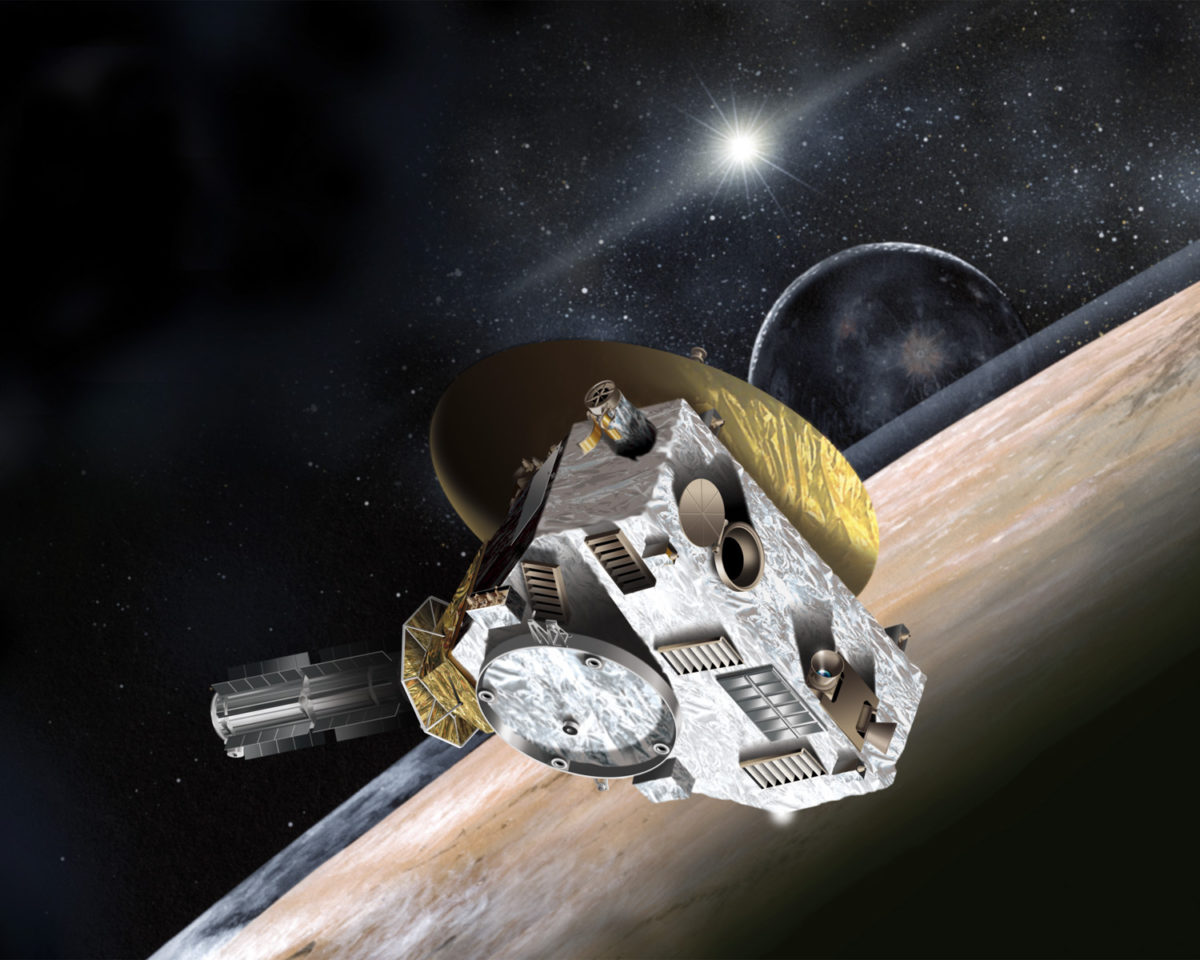

With New Horizons Ready to Wake Up, Scientists Prepare for Pluto Encounter

Somewhere deep within the suburbs of our solar system, the New Horizons spacecraft is sleeping. It's been that way since late August, when it cruised past Neptune's orbit, yawned, and entered hibernation five days later. It was the 18th and final time the spacecraft went to sleep—all part of a routine crafted to conserve the load on NASA's pricey Deep Space Network satellite dishes.

On Dec. 6, New Horizons wakes up. Inside the spacecraft's control center at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland, a flurry of activity will begin as scientists prepare the probe for its months-long encounter with Pluto, the icy is-it-a-planet-or-not world orbiting an average 6 billion kilometers from our sun. New Horizon's closest shave with Pluto occurs on July 14, 2015. The flyby will unveil details as small as the ponds in Manhattan's Central Park.

The trip to Pluto began in 2006, when New Horizons launched from Cape Canaveral, Fla. The spacecraft's Dec. 6 wake-up call is a big milestone—but not a particularly worrisome one for Alan Stern, the mission's principal investigator. After all, New Horizons has slept through 66 percent of its journey. "I don't think there's any worry in the project about whether the 18th time is different from the first 17," Stern said, speaking to reporters at the 46th annual Division for Planetary Sciences of the American Astronomical Society meeting in Tucson, Ariz. Stern, who calls the Pluto encounter the most exciting planetary reveal since Voyager 2 passed Neptune in 1989, said New Horizons' pre-programmed wakeup sequence begins at 3 p.m. EST (20:00 UTC). By 4:37 p.m., the spacecraft will be out of hibernation. It will transmit a thumbs-up signal back to Earth—a signal that won't reach home until about 9:30 p.m.

Alice Bowman, the New Horizons Mission Operations Manager, said the spacecraft will spend six weeks in a checkout phase. Ground controllers will conduct extensive checks of the probe's memory system. Two 10-gigabyte data recorders—one of which is a backup—will be formatted to hold more than 1,000 images captured during closest approach. Final command sequences will be uploaded, along with the latest Earth-calculated navigation data. "All of this is being done to prepare for the big show, which begins Jan. 15, 2015," Bowman said.

From January to April, instruments aboard New Horizons will scan Pluto as it slowly comes into focus. By May, images of the icy world will be better than those currently available from the Hubble Space Telescope. As New Horizons gets closer to the Pluto system, scientists will look for new moons and rings. They'll see how the solar wind affects the dwarf planet's atmosphere. And a high-resolution telescope will sweep the surface, looking for evidence of cryovolcanoes. Hal Weaver, a New Horizons project scientist, said that while the mission's best results will probably come from observations made around July 14, all of 2015 is game for scientific surprises." I really want to emphasize that we'll have lots of juicy science—historic science—accumulated well before the day of the closest approach," he said.

New Horizons will collect so much data, it could take up to 16 months to transmit everything back to Earth. Alan Stern said representative samples of the most important images will be sent home on a frequent basis, allowing the public to come along for the ride. After New Horizons passes Pluto, it will turn back to image the dwarf planet's dark side, which will be dimly lit by light reflected from Charon, Pluto's companion world. As New Horizons' communications with Earth are temporarily blocked by Pluto's disc, two instruments named Alice and REX will attempt to characterize Pluto's atmosphere.

From there, New Horizons will plunge deeper into the Kuiper Belt, the band of icy objects beyond Neptune, of which Pluto is a member. A detailed survey by the Hubble Space Telescope recently revealed three Kuiper Belt members that the spacecraft could reach after its Pluto encounter. The most likely target is a 30 to 45-kilometer rock that could be visited in January 2019, at a cost of just 35 percent of New Horizons' remaining fuel. From an official standpoint, the extended mission doesn't yet exist, but it seems unlikely NASA would eschew the chance to re-purpose a healthy spacecraft for another one-of-a-kind flyby.

As Pluto is slowly revealed, the debate on its planethood status will likely reach a fever pitch. Stern, a longtime leader in the pro-planet camp, seems less concerned with semantics and more excited about showing Pluto off for what it is: the representative of a class of never-before-seen objects. "From when Pluto was discovered in 1930 to the 1990s, we wondered why it was a misfit in the architecture of the solar system," he said, turning to look at a chart of thousands of now-known Kuiper Belt objects. "Who's the misfit now?"

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth