Marc Rayman • Jun 30, 2015

Dawn Journal: Ceres' Intriguing Geology

Dear Evidawnce-Based Readers,

Dawn is continuing to unveil a Ceres of mysteries at the first dwarf planet discovered. The spacecraft has been extremely productive, returning a wealth of photographs and other scientific measurements to reveal the nature of this exotic alien world of rock and ice. First glimpsed more than 200 years ago as a dot of light among the stars, Ceres is the only dwarf planet between the sun and Neptune.

Dawn has been orbiting Ceres every 3.1 days at an altitude of 2,700 miles (4,400 kilometers). As described last month, the probe aimed its powerful sensors at the strange landscape throughout each long, slow passage over the side of Ceres facing the sun. Meanwhile, Ceres turned on its axis every nine hours, presenting itself to the ambassador from Earth. On the half of each revolution when Dawn was above ground that was cloaked in the darkness of night, it pointed its main antenna to that planet far, far away and radioed its precious findings to eager Earthlings (although the results will be available for others throughout the cosmos as well). Dawn began this second mapping campaign (also known as “survey orbit”) on June 5, and tomorrow it will complete its eighth and final revolution.

The spacecraft made most of its observations by looking straight down at the terrain directly beneath it. During portions of its first, second and fourth orbits, however, Dawn peered at the limb of Ceres against the endless black of space, seeing the sights from a different perspective to gain a better sense of the lay of the land.

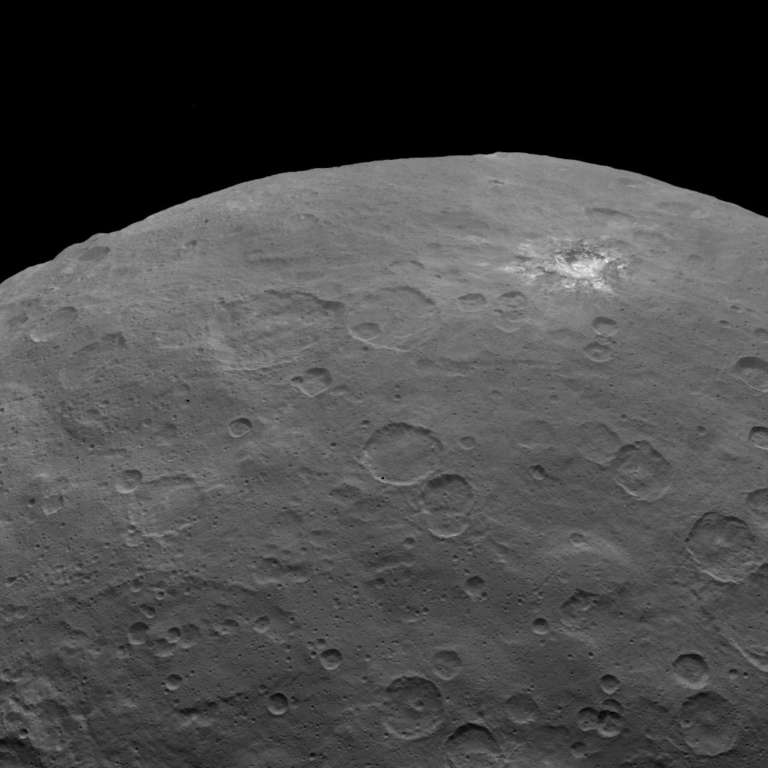

And what marvels Dawn has beheld! How can you not be mesmerized by the luminous allure of the famous bright spots? They are not, in fact, a source of light, but for a reason that remains elusive, the ground there reflects much more sunlight than elsewhere. Still, it is easy to imagine them as radiating a light all their own, summoning space travelers from afar, beckoning the curious and the bold to venture closer in return for an attractive reward. And that is exactly what we will do, as we seek the rewards of new knowledge and new insights into the cosmos.

Although scientists have not yet determined what minerals are there, Dawn will gather much more data. As summarized in this table, our explorer will map Ceres again from much closer during the course of its orbital mission. New bright areas have shown up in other locations too, in some places as relatively small spots, in others as larger areas (as in the photo below), and all of them will come into sharper focus when Dawn descends further.

In the meantime, you can register your opinion for what the bright spots are. Join more than 100 thousand others who have voted for an explanation for this enigma. Of course, Ceres will be the ultimate arbiter, and nature rarely depends upon public opinion, but the Dawn project will consider sending the results of the poll to Ceres, courtesy of our team member on permanent assignment there.

In addition to the bright spots, Dawn’s views from its present altitude have included a wide range of other intriguing sights, as one would expect on a world of more than one million square miles (nearly 2.8 million square kilometers). There are myriad craters excavated by objects falling from space, inevitable scars from inhabiting the main asteroid belt for more than four billion years, even for the largest and most massive resident there.

The craters exhibit a wide range of appearances, not only in size but also in how sharp and fresh or how soft and aged they look. Some display a peak at the center. A crater can form from such a powerful punch that the hard ground practically melts and flows away from the impact site. Then the material rebounds, almost as if it sloshes back, while already cooling and then solidifying again. The central peak is like a snapshot, preserving a violent moment in the formation of the crater. By correlating the presence or absence of central peaks with the sizes of the craters, scientists can infer properties of Ceres’ crust, such as how strong it is. Rather than a peak at the center, some craters contain large pits, depressions that may be a result of gases escaping after the impact. (Craters elsewhere in the solar system, including on Vesta and Mars, also have pits.)

Dawn also has spied many long, straight or gently curved canyons. Geologists have yet to determine how they formed, and it is likely that several different mechanisms are responsible. For example, some might turn out to be the result of the crust of Ceres shrinking as the heat and other energy accumulated upon formation gradually radiated into space. When the behemoth slowly cooled, stresses could have fractured the rocky, icy ground. Others might have been produced as part of the devastation when a space rock crashed, rupturing the terrain.

Ceres shows other signs of an active past rather than that of a static chunk of inert material passing the eons with little notice. Some areas are less densely cratered than others, suggesting that there are geological processes that erase the craters. Indeed, some regions look as if something has flowed over them, as if perhaps there was mud or slush on the surface.

In addition to evidence of aging and renewal, some powerful internal forces have uplifted mountains. One particularly striking structure is a steep cone that juts three miles (five kilometers) high in an otherwise relatively smooth area, looking to an untrained (but transfixed) eye like a volcanic cone, a familiar sight on your home planet (or, at least, on mine). No other isolated, prominent protuberance has been spotted on Ceres.

It is too soon for scientists to understand the intriguing geology of this ancient world, but the prolific adventurer is providing them with the information they will use. The bounty from this second mapping phase includes more than 1,600 pictures covering essentially all of Ceres, well over five million spectra in visible and infrared wavelengths and hundreds of hours of gravity measurements.

The spacecraft has performed its ambitious assignments quite admirably. Only a few deviations from the very elaborate plans occurred. On June 15 and 27, during the fourth and eighth flights over the dayside, the computer in the combination visible and infrared mapping spectrometer (VIR) detected an unexpected condition, and it stopped collecting data. When the spacecraft’s main computer recognized the situation, it instructed VIR to close its protective cover and then power down. The unit dutifully did so. Also on June 27, about three hours before VIR’s interruption, the camera’s computer experienced something similar.

Most of the time that Dawn points its sensors at Ceres, it simultaneously broadcasts through one of its auxiliary radio antennas, casting a very wide but faint signal in the general direction of Earth. (As Dawn progresses in its orbit, the direction to Earth changes, but the spacecraft is equipped with three of these auxiliary antennas, each pointing in a different direction, and mission controllers program it to switch antennas as needed.) The operations team observed what had occurred in each case and recognized there was no need to take immediate action. The instruments were safe and Dawn continued to carry out all of its other tasks.

When Dawn subsequently flew to the nightside of Ceres and pointed its main antenna to Earth, it transmitted much more detailed telemetry. As engineers and scientists continue their careful investigations, they recognize that in many ways, these events appear very similar to ones that have occurred at other times in the mission.

Four years ago, VIR’s computer reset when Dawn was approaching Vesta, and the most likely cause was deemed to be a cosmic ray strike. That’s life in deep space! It also reset twice in the survey orbit phase at Vesta. The camera reset three times in the first three months of the low altitude mapping orbit at Vesta.

Even with the glitches in this second mapping orbit, Dawn’s outstanding accomplishments represent well more than was originally envisioned or written into the mission’s scientific requirements for this phase of the mission. For those of you who have not been to Ceres or aren’t going soon (and even those of you who want to plan a trip there of your own), you can see what Dawn sees by going to the image gallery.

Although Dawn already has revealed far, far more about Ceres in the last six months than had been seen in the preceding two centuries of telescopic studies, the explorer is not ready to rest on its laurels. It is now preparing to undertake another complex spiral descent, using its sophisticated ion propulsion system to maneuver to a circular orbit three times as close to the dwarf planet as it is now. It will take five weeks to perform the intricate choreography needed to reach the third mapping altitude, starting tomorrow night. You can keep track of the spaceship’s flight as it propels itself to a new vantage point for observing Ceres by visiting the mission status page or following it on Twitter @NASA_Dawn.

As Dawn moves closer to Ceres, Earth will be moving closer as well. Earth and Ceres travel on independent orbits around the sun, the former completing one revolution per year (indeed, that’s what defines a year) and the latter completing one revolution in 4.6 years (which is one Cerean year). (We have discussed before why Earth revolves faster in its solar orbit, but in brief it is because being closer to the sun, it needs to move faster to counterbalance the stronger gravitational pull.) Of course, now that Dawn is in a permanent gravitational embrace with Ceres, where Ceres goes, so goes Dawn. And they are now and forever more so close together that the distance between Earth and Ceres is essentially equivalent to the distance between Earth and Dawn.

On July 22, Earth and Dawn will be at their closest since June 2014. As Earth laps Ceres, they will be 1.94 AU (180 million miles, or 290 million kilometers) apart. Earth will race ahead on its tight orbit around the sun, and they will be more than twice as far apart early next year.

Although Dawn communicates regularly with Earth, it left that planet behind nearly eight years ago and will keep its focus now on its new residence. With two very successful mapping campaigns complete, its next priority is to work its way down through Ceres’ gravitational field to an altitude of about 900 miles (less than 1,500 kilometers). With sharper views and new kinds of observations (including stereo photography), the treasure trove obtained by this intrepid extraterrestrial prospector will only be more valuable. Everyone who longs for new understandings and new perspectives on the cosmos will grow richer as Dawn continues to pioneer at a mysterious and distant dwarf planet.

Dawn is 2,700 miles (4,400 kilometers) from Ceres. It is also 2.01 AU (187 million miles, or 301 million kilometers) from Earth, or 785 times as far as the moon and 1.98 times as far as the sun today. Radio signals, traveling at the universal limit of the speed of light, take 33 minutes to make the round trip.

Dr. Marc D. Rayman

10:00 p.m. PDT June 29, 2015

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth